Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

| Lynch syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Micrograph showing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (in a colorectal cancer), a finding associated with MSI-H tumours, as may be seen in Lynch syndrome. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty |

Oncology |

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic condition that has a high risk of colon cancer[1] as well as other cancers including endometrial cancer (second most common), ovary, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, upper urinary tract, brain, and skin. The increased risk for these cancers is due to inherited mutations that impair DNA mismatch repair. It is a type of cancer syndrome.

Signs and symptoms

Tumoral predisposition

- Colorectal cancer

- Endometrial carcinoma

- Digestive adenoma: gastric adenoma, pyloric gland adenoma,[2] duodenal adenoma, intestinal adenoma

- Ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma

Risk of cancer

Individuals with HNPCC have about an 80% lifetime risk for colon cancer. Two-thirds of these cancers occur in the proximal colon. The mean age of colorectal cancer diagnosis is 44 for members of families that meet the Amsterdam criteria. Also, women with HNPCC have an 80% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer. The average age of diagnosis of endometrial cancer is about 46 years. Among women with HNPCC who have both colon and endometrial cancer, about half present first with endometrial cancer, making endometrial cancer the most common sentinel cancer in Lynch syndrome.[3] In HNPCC, the mean age of diagnosis of gastric cancer is 56 years of age with intestinal-type adenocarcinoma being the most commonly reported pathology. HNPCC-associated ovarian cancers have an average age of diagnosis of 42.5 years-old; approximately 30% are diagnosed before age 40. Other HNPCC-related cancers have been reported with specific features: the urinary tract cancers are transitional carcinoma of the ureter[4] and renal pelvis; small bowel cancers occur most commonly in the duodenum and jejunum; the central nervous system tumor most often seen is glioblastoma.

A large follow up study (3119 patients; average follow up 24 years) has found significant variation in the cancer rates depending on the mutation involved.[5] Up to the age of 75 years the risks of colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, upper gastrointestinal (gastric, duodenal, bile duct or pancreatic), urinary tract cancers, prostate cancer and brain tumours were as follows: for MLH1 mutations the risk was - 46%, 43%, 10%, 21%, 8%, 17% and 1% respectively: for MSH2 mutations the risks were 57%, 17%, 10%, 25%, 32%, and 5% respectively: for MSH6 mutations the risks were 15%, 46%, 13%, 7%, 11%, 18% and 1% respectively.

| Gene | Ovarian cancer risk | Endometrial cancer risk |

|---|---|---|

| MLH1 | 4-24% | 25-60% |

| MSH2/EPCAM | 4-24% | 25-60% |

| MSH6 | 1-11% | 16-26% |

| PMS2 | 6% (combined risk) | 15% |

Genetics

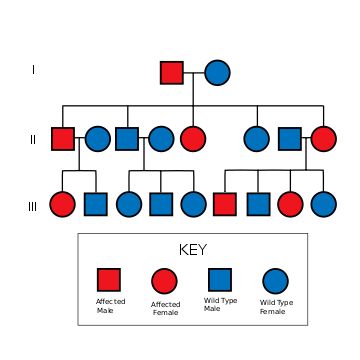

HNPCC is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. The hallmark of HNPCC is defective DNA mismatch repair, which leads to microsatellite instability, also known as MSI-H (the H is "high"). MSI is identifiable in cancer specimens in the pathology laboratory.[7] Most cases result in changes in the lengths of dinucleotide repeats of the nucleobases cytosine and adenine (sequence: CACACACACA...).[8]

However, as in cancer resulting from autosomal dominant germline tumor suppressor gene mutations, such as familial adenomatous polyposis, for malignancy to develop in HNPCC a second deleterious mismatch-repair gene mutation at the same locus in the homologous chromosome is required to occur at the cellular, or somatic, level.

HNPCC is known to be associated with mutations in genes involved in the DNA mismatch repair pathway:

| OMIM name | Genes implicated in HNPCC | Frequency of mutations in HNPCC families | Locus | First publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNPCC1 (120435) | MSH2/EPCAM | approximately 60% | 2p22 | Fishel 1993[9] |

| HNPCC2 (609310) | MLH1 | approximately 30% | 3p21 | Papadopoulos 1994[10] |

| HNPCC5 | MSH6 | 7-10% | 2p16 | Miyaki 1997[11] |

| HNPCC4 | PMS2 | relatively infrequent | 7p22[12] | Nicolaides 1994 |

| HNPCC3 | PMS1 | case report[12] | 2q31-q33 | Nicolaides 1994 |

| HNPCC6 | TGFBR2 | case report[13] | 3p22 | |

| HNPCC7 | MLH3 | disputed[14] | 14q24.3 | |

Patients with MSH6 mutations are more likely to be Amsterdam criteria II-negative.[15] The presentation with MSH6 is slightly different than with MLH1 and MSH2, and the term "MSH6 syndrome" has been used to describe this condition.[16] In one study, the Bethesda guidelines were more sensitive than the Amsterdam Criteria in detecting it.[17]

Up to 39% of families with mutations in an HNPCC gene do not meet the Amsterdam criteria. Therefore, families found to have a deleterious mutation in an HNPCC gene should be considered to have HNPCC regardless of the extent of the family history. This also means that the Amsterdam criteria fail to identify many patients at risk for Lynch syndrome. Improving the criteria for screening is an active area of research, as detailed in the Screening Strategies section of this article.

HNPCC is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Most people with HNPCC inherit the condition from a parent. However, due to incomplete penetrance, variable age of cancer diagnosis, cancer risk reduction, or early death, not all patients with an HNPCC gene mutation have a parent who had cancer. Some patients develop HNPCC de-novo in a new generation, without inheriting the gene. These patients are often only identified after developing an early-life colon cancer. Parents with HNPCC have a 50% chance of passing the genetic mutation on to each child.

Diagnosis

The Amsterdam clinical criteria identifies candidates for genetic testing, and genetic testing can make a diagnosis of Lynch syndrome. Genetic testing is commercially available and consists of a blood test.

Classification

Three major groups of MSI-H (microsatellite instability – MSI) cancers can be recognized by histopathological criteria:

- right-sided poorly differentiated cancers

- right-sided mucinous cancers

- adenocarcinomas in any location showing any measurable level of intraepithelial lymphocyte (TIL)

In addition, HNPCC can be divided into Lynch syndrome I (familial colon cancer) and Lynch syndrome II (HNPCC associated with other cancers of the gastrointestinal tract or reproductive system).[18]

Prevention

After reporting a null finding from their randomized controlled trial of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid – ASA) to prevent the colorectal neoplasia of Lynch syndrome,[19] Burn and colleagues have reported new data, representing a longer follow-up period than reported in the initial NEJM paper. These new data demonstrate a reduced incidence in Lynch syndrome patients who were exposed to at least four years of high-dose aspirin, with a satisfactory risk profile.[20] These results have been widely covered in the media; future studies will look at modifying (lowering) the dose (to reduce risk associated with the high dosage of ASA).

Screening

Genetic testing for mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes is expensive and time-consuming, so researchers have proposed techniques for identifying cancer patients who are most likely to be HNPCC carriers as ideal candidates for genetic testing. The Amsterdam Criteria (see below) are useful, but do not identify up to 30% of potential Lynch syndrome carriers. In colon cancer patients, pathologists can measure microsatellite instability in colon tumor specimens, which is a surrogate marker for DNA mismatch repair gene dysfunction. If there is microsatellite instability identified, there is a higher likelihood for a Lynch syndrome diagnosis. Recently, researchers combined microsatellite instability (MSI) profiling and immunohistochemistry testing for DNA mismatch repair gene expression and identified an extra 32% of Lynch syndrome carriers who would have been missed on MSI profiling alone. Currently, this combined immunohistochemistry and MSI profiling strategy is the most advanced way of identifying candidates for genetic testing for Lynch syndrome.

Genetic counseling and genetic testing are recommended for families that meet the Amsterdam criteria, preferably before the onset of colon cancer.

A transvaginal ultrasound with or without endometrial biopsy is recommended annually for ovarian and endometrial cancer screening.[6]

Amsterdam criteria

The following are the Amsterdam criteria in identifying high-risk candidates for molecular genetic testing:[21]

Amsterdam Criteria (all bullet points must be fulfilled):

- Three or more family members with a confirmed diagnosis of colorectal cancer, one of whom is a first degree (parent, child, sibling) relative of the other two

- Two successive affected generations

- One or more colon cancers diagnosed under age 50 years

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) has been excluded

Amsterdam Criteria II (all bullet points must be fulfilled):

- Three or more family members with HNPCC-related cancers, one of whom is a first-degree relative of the other two

- Two successive affected generations

- One or more of the HNPCC-related cancers diagnosed under age 50 years

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) has been excluded

Surgery

Prophylactic hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the uterus, Fallopian tubes, and ovaries to prevent cancer from developing) can be performed before ovarian or endometrial cancer develops.[6]

Treatment

Surgery remains the front-line therapy for HNPCC. There is an ongoing controversy over the benefit of 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapies for HNPCC-related colorectal tumours, particularly those in stages I and II.[22]

Epidemiology

In the United States, about 160,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are diagnosed each year. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer is responsible for approximately 2 percent to 7 percent of all diagnosed cases of colorectal cancer. The average age of diagnosis of cancer in patients with this syndrome is 44 years old, as compared to 64 years old in people without the syndrome.[23]

Terminology

Henry T. Lynch, Professor of Medicine at Creighton University Medical Center, characterized the syndrome in 1966.[24] In his earlier work, he described the disease entity as "cancer family syndrome." The term "Lynch syndrome" was coined in 1984 by other authors; Lynch named the condition HNPCC in 1985. Since then the two terms have been used interchangeably, until later advances in the understanding of the genetics of the disease led to the term HNPCC falling out of favour.[25]

Other sources reserve the term "Lynch syndrome" when there is a known DNA mismatch repair defect, and use the term "familial colorectal cancer type X" when the Amsterdam criteria are met but there is no known DNA mismatch repair defect.[26] The putative "type X" families appear to have a lower overall incidence of cancer and lower risk for non-colorectal cancers than families with documented DNA mismatch repair deficiency.[27] About 35% of patients meeting Amsterdam criteria do not have a DNA-mismatch-repair gene mutation.[28]

Complicating matters is the presence of an alternative set of criteria, known as the "Bethesda Guidelines."[29][30][31]

Representative organisations

There are a number of non-profit organisations providing information and support, including Lynch Syndrome International, Lynch Syndrome UK[32] and Bowel Cancer UK.[33] In the US, National Lynch Syndrome Awareness Day is March 22.[34]

References

- ↑ Kastrinos F, Mukherjee B, Tayob N, Wang F, Sparr J, Raymond VM, Bandipalliam P, Stoffel EM, Gruber SB, Syngal S (October 2009). "Risk of pancreatic cancer in families with Lynch syndrome". JAMA. 302 (16): 1790–5. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1529. PMC 4091624. PMID 19861671.

- ↑ Lee SE, Kang SY, Cho J, Lee B, Chang DK, Woo H, Kim JW, Park HY, Do IG, Kim YE, Kushima R, Lauwers GY, Park CK, Kim KM (June 2014). "Pyloric gland adenoma in Lynch syndrome". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 38 (6): 784–92. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000185. PMC 4014525. PMID 24518125.

- ↑ Hoffman BL (2012). "Chapter 33: Endometrial Cancer". Williams Gynecology (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0071716727.

- ↑ Valenzuela CD, Moore HG, Huang WC, Reich EW, Yee H, Ostrer H, Pachter HL (December 2009). "Three synchronous primary carcinomas in a patient with HNPCC associated with a novel germline mutation in MLH1: Case report". World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 7 (7): 94. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-7-94. PMC 2795749. PMID 19995443.

- ↑ Mallorca Group, Møller P, Seppälä TT, Bernstein I, Holinski-Feder E, Sala P, et al. (July 2017). "Cancer risk and survival inpath_MMRcarriers by gene and gender up to 75 years of age: a report from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database". Gut. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314057. PMID 28754778.

- 1 2 3 Ring KL, Garcia C, Thomas MH, Modesitt SC (November 2017). "Current and future role of genetic screening in gynecologic malignancies". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 217 (5): 512–521. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.011. PMID 28411145.

- ↑ Pathology of Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer - JASS 910 (1): 62 - Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences Archived 2006-06-19 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Oki E, Oda S, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K (March 1999). "Mutated gene-specific phenotypes of dinucleotide repeat instability in human colorectal carcinoma cell lines deficient in DNA mismatch repair". Oncogene. 18 (12): 2143–7. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202583. PMID 10321739.

- ↑ Fishel R, Lescoe MK, Rao MR, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Garber J, Kane M, Kolodner R (December 1993). "The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer". Cell. 75 (5): 1027–38. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90546-3. PMID 8252616.

- ↑ Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides NC, Wei YF, Ruben SM, Carter KC, Rosen CA, Haseltine WA, Fleischmann RD, Fraser CM, Adams MD (March 1994). "Mutation of a mutL homolog in hereditary colon cancer". Science. 263 (5153): 1625–9. doi:10.1126/science.8128251. PMID 8128251.

- ↑ Miyaki M, Konishi M, Tanaka K, Kikuchi-Yanoshita R, Muraoka M, Yasuno M, Igari T, Koike M, Chiba M, Mori T (November 1997). "Germline mutation of MSH6 as the cause of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer". Nature Genetics. 17 (3): 271–2. doi:10.1038/ng1197-271. PMID 9354786.

- 1 2 Nicolaides NC, Papadopoulos N, Liu B, Wei YF, Carter KC, Ruben SM, Rosen CA, Haseltine WA, Fleischmann RD, Fraser CM (September 1994). "Mutations of two PMS homologues in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer". Nature. 371 (6492): 75–80. doi:10.1038/371075a0. PMID 8072530.

- ↑ Lu SL, Kawabata M, Imamura T, Akiyama Y, Nomizu T, Miyazono K, Yuasa Y (May 1998). "HNPCC associated with germline mutation in the TGF-beta type II receptor gene". Nature Genetics. 19 (1): 17–8. doi:10.1038/ng0598-17. PMID 9590282.

- ↑ Ou J, Rasmussen M, Westers H, Andersen SD, Jager PO, Kooi KA, Niessen RC, Eggen BJ, Nielsen FC, Kleibeuker JH, Sijmons RH, Rasmussen LJ, Hofstra RM (April 2009). "Biochemical characterization of MLH3 missense mutations does not reveal an apparent role of MLH3 in Lynch syndrome". Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 48 (4): 340–50. doi:10.1002/gcc.20644. PMID 19156873.

- ↑ Ramsoekh D, Wagner A, van Leerdam ME, Dinjens WN, Steyerberg EW, Halley DJ, Kuipers EJ, Dooijes D (November 2008). "A high incidence of MSH6 mutations in Amsterdam criteria II-negative families tested in a diagnostic setting". Gut. 57 (11): 1539–44. doi:10.1136/gut.2008.156695. PMID 18625694.

- ↑ Suchy J, Lubinski J (June 2008). "MSH6 syndrome". Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice. 6 (2): 103–4. doi:10.1186/1897-4287-6-2-103. PMC 2735474. PMID 19804606.

- ↑ Goldberg Y, Porat RM, Kedar I, Shochat C, Galinsky D, Hamburger T, Hubert A, Strul H, Kariiv R, Ben-Avi L, Savion M, Pikarsky E, Abeliovich D, Bercovich D, Lerer I, Peretz T (June 2010). "An Ashkenazi founder mutation in the MSH6 gene leading to HNPCC". Familial Cancer. 9 (2): 141–50. doi:10.1007/s10689-009-9298-9. PMID 19851887.

- ↑ Hereditary Colorectal Cancer > Background. From Medscape. By Juan Carlos Munoz and Louis R Lambiase. Updated: Oct 31, 2011

- ↑ Burn J, Bishop DT, Mecklin JP, Macrae F, Möslein G, Olschwang S, Bisgaard ML, Ramesar R, Eccles D, Maher ER, Bertario L, Jarvinen HJ, Lindblom A, Evans DG, Lubinski J, Morrison PJ, Ho JW, Vasen HF, Side L, Thomas HJ, Scott RJ, Dunlop M, Barker G, Elliott F, Jass JR, Fodde R, Lynch HT, Mathers JC (December 2008). "Effect of aspirin or resistant starch on colorectal neoplasia in the Lynch syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (24): 2567–78. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801297. PMID 19073976.

- ↑ "Aspirin Confers Long-Term Protective Effect in Lynch Syndrome Patients". Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ↑ Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT (June 1999). "New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC". Gastroenterology. 116 (6): 1453–6. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70510-X. PMID 10348829.

- ↑ Boland CR, Koi M, Chang DK, Carethers JM (2007). "The biochemical basis of microsatellite instability and abnormal immunohistochemistry and clinical behavior in Lynch syndrome: from bench to bedside". Familial Cancer. 7 (1): 41–52. doi:10.1007/s10689-007-9145-9. PMC 2847875. PMID 17636426.

- ↑ Cancer Information, Research, and Treatment for all Types of Cancer | OncoLink Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lynch HT, Shaw MW, Magnuson CW, Larsen AL, Krush AJ (February 1966). "Hereditary factors in cancer. Study of two large midwestern kindreds". Archives of Internal Medicine. 117 (2): 206–12. doi:10.1001/archinte.117.2.206. PMID 5901552.

- ↑ Bellizzi AM, Frankel WL (November 2009). "Colorectal cancer due to deficiency in DNA mismatch repair function: a review". Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 16 (6): 405–17. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6bdc. PMID 19851131.

- ↑ Lindor NM (October 2009). "Familial colorectal cancer type X: the other half of hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome". Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. 18 (4): 637–45. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2009.07.003. PMC 3454516. PMID 19793571.

- ↑ Lindor NM, Rabe K, Petersen GM, Haile R, Casey G, Baron J, Gallinger S, Bapat B, Aronson M, Hopper J, Jass J, LeMarchand L, Grove J, Potter J, Newcomb P, Terdiman JP, Conrad P, Moslein G, Goldberg R, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H, de Andrade M, Siegmund K, Thibodeau SN, Boardman LA, Seminara D (April 2005). "Lower cancer incidence in Amsterdam-I criteria families without mismatch repair deficiency: familial colorectal cancer type X". JAMA. 293 (16): 1979–85. doi:10.1001/jama.293.16.1979. PMC 2933042. PMID 15855431.

- ↑ Scott RJ, McPhillips M, Meldrum CJ, Fitzgerald PE, Adams K, Spigelman AD, du Sart D, Tucker K, Kirk J (January 2001). "Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer in 95 families: differences and similarities between mutation-positive and mutation-negative kindreds". American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (1): 118–127. doi:10.1086/316942. PMC 1234904. PMID 11112663.

- ↑ Gologan A, Krasinskas A, Hunt J, Thull DL, Farkas L, Sepulveda AR (November 2005). "Performance of the revised Bethesda guidelines for identification of colorectal carcinomas with a high level of microsatellite instability". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 129 (11): 1390–7. doi:10.1043/1543-2165(2005)129[1390:POTRBG]2.0.CO;2. PMID 16253017.

- ↑ Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, Syngal S, de la Chapelle A, Rüschoff J, Fishel R, Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Hamelin R, Hamilton SR, Hiatt RA, Jass J, Lindblom A, Lynch HT, Peltomaki P, Ramsey SD, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Vasen HF, Hawk ET, Barrett JC, Freedman AN, Srivastava S (February 2004). "Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 96 (4): 261–8. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh034. PMC 2933058. PMID 14970275.

- ↑ Lipton LR, Johnson V, Cummings C, Fisher S, Risby P, Eftekhar Sadat AT, Cranston T, Izatt L, Sasieni P, Hodgson SV, Thomas HJ, Tomlinson IP (December 2004). "Refining the Amsterdam Criteria and Bethesda Guidelines: testing algorithms for the prediction of mismatch repair mutation status in the familial cancer clinic". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 22 (24): 4934–43. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.11.084. PMID 15611508.

- ↑ "Lynch Syndrome UK". Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ "Bowel Cancer UK: Lynch Syndrome". Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ "CDC: March 22nd is National Lynch Syndrome Awareness Day!". Retrieved 31 March 2018.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |