Lower Assam

| Lower Assam | ||

| Western Assam, Kamrup (Ancient and medieval) | ||

| Region | ||

|

||

| Country | India | |

|---|---|---|

| City | Guwahati | |

| Capital | Pragjyotishpura and Durjaya (Ancient) | |

| Population | 11,253,550 (2011) | |

| Timezone | UTC+05:30 (IST) (UTC+5.30) | |

Lower Assam (also Western Assam), "Kamrup" (ancient, medieval and pre-colonial); is a region situated in Western Brahmaputra Valley.

The term "Lower Assam" is often a misnomer in spite of popular usage to refer the region. In scholary circles Western Assam was more frequently used to accurately define the region and differentiate it from Lower Assam Division.

Soon after the formal creation of the British districts in 1833, Lower Assam denoted one of the five initial districts that were created west of the Dhansiri river,[1] which, along with the six paraganas, became a single district of Kamrup in 1836.[2]

It was home to the mighty kingdom of Kamarupa (3–12 AD), ruled by Varman's and Pala's from their capital's Pragjyotishpura (Guwahati) and Durjaya (North Gauhati). Today Guwahati is the largest city of North-East India while Dispur, the capital of Assam, is within the town.

Etymology

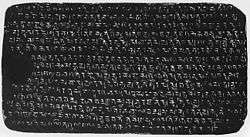

In the 4th-century, the region was mentioned as Kamarupa (Western Assam) in the Prayag stone inscription along with Davaka (central Assam).[3]Davaka was absorbed during the period between 5th-7th century,[4][5] [6]

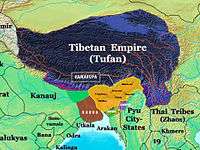

Medieval Muslim invaders continue to refer the region as Kamrup. Easternmost parts of the region (modern Kamrup) briefly became parts of Koch kingdom, Mughal empire and Ahom kingdom,[7] until annexation of Eastern Assam by Burmese empire.

With British occupation in the nineteenth century, Goalpara region became part of Colonial Assam, while western Kamrup (North Bengal) was merged with Bengal. In the second half of nineteenth century region became part of Lower Assam Division, along with Darrang, Nagaon, Khasi and Jaintia hills. The modern Western Assam and North Bengal, historically Kamrup,[8] referred as Western Assam from colonial times and later.

History

Region was mentioned in Hindu epics as Pragjyotisha. Legends of king Naraka, Bhagadatta and Vajradatta has considerable part in Indian mythology. First historical mention of region was found in Arthashastra of Kautilya in 400 B.C., where he mentioned about flourishing trade between Maurya Empire and Kamarupa. Pragya stone pillar mentioned it as frontier kingdom along with Davaka of central Assam. Region served as capital of ancient Kamrup kingdom till its end,[9] centered around modern Kamrup region.

Varman Dynasty

Pushyavarman (350–374) named after Pushyamitra Shunga, became the first ruler of Kamrup as founder ruler of Varman Dynasty. His son Samudravarman (374–398), named after Samudragupta, was accepted as an overlord by many local rulers. Narayanavarman (494–518) and his son Bhutivarman (518–542) offered the Ashwamedha; and as the Nidhanpur inscription of Bhaskaravarman avers, these expansions included the region of Chandrapuri Visaya, identified with present-day Sylhet division. Thus, the small but powerful kingdom that Pushyavarman established grew in fits and starts over many generations of kings and expanded to include adjoining possibly smaller kingdoms and parts of Bangladesh covering most part of Eastern India, much larger area than modern Kamrup from which it initially begins. After the initial expansion till the beginning of Bhutivarman's reign, the kingdom came under attack from Yasodharman (525–535) of Malwa, the first major assault from the west. Though it is unclear what the effect of this invasion was on the kingdom; that Bhutivarman's grandson, Sthitavarman (566–590), enjoyed victories over the Gauda of Karnasuvarna and performed two aswamedha ceremonies suggests that the Kamarupa kingdom had recovered nearly in full. His son, Susthitavarman (590–600) came under the attack of Mahasenagupta of East Malwa. These back and forth invasions were a result of a system of alliances that pitted the Kamarupa kings (allied to the Maukharis) against the Gaur kings (allied with the East Malwa kings). Susthitavarman died as the Gaur invasion was on, and his two sons, Supratisthitavarman and Bhaskaravarman fought against an elephant force and were captured and taken to Gaur. They were able to regain their kingdom. Suprathisthitavarman's reign is given as 595–600, a very short period, at the end of which he died without an heir.

Supratisthitavarman was succeeded by his brother, Bhaskaravarman (600–650), the most illustrious of the Varman kings who succeeded in turning his kingdom and invading the very kingdom that had taken him captive. Bhaskaravarman had become strong enough to offer his alliance with Harshavardhan just as the Thanesar king ascended the throne in 606 after the murder of his brother, the previous king, by Shashanka of Gaur. Harshavardhana finally took control over the kingless Maukhari kingdom and moved his capital to Kanauj. The alliance between Harshavardhana and Bhaskaravarman squeezed Shashanka from either side and reduced his kingdom, making Shasanka escaping to hills further south near modern Bengali-Orissan border. This decisive victory leads to takeover of most of Gauda kingdom by Bhaskaravarman. He issued the Nidhanpur copper-plate inscription from his victory camp in the Gaur capital Karnasuvarna (present-day Murshidabad, West Bengal) to replace a grant issued earlier by Bhutivarman for a settlement in the Sylhet region of present-day Bangladesh.

In about 643, Xuanzang (Xuanzang/Hiuen Tsang) visited Bhaskaravarman's court and recorded details of his kingdom. Xuanzang mentioned the western border of the Kamarupa kingdom was the Karatoya river and eastern boundary as Dikkaravasini (Sadiya). At the end of this visit, Bhaskaravarman accompanied Xuanzang to Kanauj, and participated in a religious assembly and a festival at Prayaga (Allahabad) with Harshavardhana, spending more than a year away from his own kingdom. Assembly was participated by eighteen vassal kings, while Bhaskaravarman impersonated as "Brahma", Harsha kept himself the subordinate position of "Indra". It seems Bhaskaravarman maintained relations with China. He recounted to Xuanzang a Chinese song about the Jin dynasty which became very popular in his kingdom. In 648 A.D after the death of Harshavardhana, Wang-Hiuen-ts'oe was sent on a mission to India with Tsiang Cheu-jenn as his second in command was helped by Bhaskaravarman, according to a Chinese account. Bhaskaravarman, also called Kumar, or Shri Kumar, was a bachelor king and died without an heir.

Pala Dynasty

Brahma Pala (900–920), was founder Pala Dynasty (900–1100 A.D) of Kamarupa. Dynasty ruled from its capital Durjaya, modern-day North Guwahati. The greatest of the Pala kings, Dharma Pala had his capital at Kamarupa Nagara, now identified with North Guwahati. Ratna Pala was another notable sovereign of this line. Records of his land-grants have been found at Bargaon and Sualkuchi, while a similar relic of Indra Pala, has been discovered at Guwahati. Pala dynasty come to end with Jaya Pala (1075–1100).[10]

People

Demography

According to 2011 census, Western Assam has total population of 1,12,53,550; out of which urban population accounting to 19,59,707 while rural population is 92,93,843.

Ethnic division

The ethnic composition of the region is diverse. Aryans composed of Kamrupi and Goalpariya people are majority. It has considerable number of tribal population consisting Bodo, Rabha, Nepali and Koch in the north, south and southwest.

Culture

Villages still contained the traditional Vedic culture, while in case of towns and cities it relaxed a bit. Western Assamese culture largely flourished in the reign of Pushyavarman (350-374), the founder of great Varman dynasty of Kamrup Kingdom which reached its zenith in the reign of Bhaskaravarman (600–650). Scholars believe Kamrupi culture had a distinctive mark in every sphere, whether it be science or literature. Astronomy is a Kamrupi science. Daka, the great Kamrupi poet flourished undoubtedly during the ancient period.[11]

Festivals

Durga Puja, Kali Puja and other Pujas; Diwali, Holi, Janmastami, Shivratri to name a few, are major festivals of the region. Muslims celebrate Eid. There is hardly any dance and music of the Bihu type so common in Eastern Assam, but a special spring time festival of this region is a fair usually held in the first week of Baihag or third week of April. It is known as "Bhatheli" in northern Kamrup, "Sori" or "Suanri" in southern Kamrup.[12] In certain areas the breakers of the "bhatheli-ghar" come from another village, resulting in a sort of mock fight between them and the local youth. In the southern part of Kamrup, where the festival is known as Sori, planting of tall bamboos is not seen, but bamboo posts,with the tuft at the top. People bow before the bamboos in northern Kamrup and they also touch them with reverence, but it does not look like any sort of bamboo worship.[13] The common popular term to designate the three festivals corresponding to Bihu of Eastern Assam, in Western Assam, except in West Goalpara, is "Domahi", e.g., "Baihagar Domahi", "Maghar Domahi" and "Katir Domahi".[14][15]

Religion

Hinduism and Islam are major religions of the region. Hinduism is further divided into Vaishnavism and Shaktism. Hindu way of life can be observed in dressing, food and lifestyle, an important aspect of cultural identity for people of the region.

Hindu kingdoms as political identities made a long-lasting impact on region defining the way of the life. In the early part of second millennium, Islam arrived in the region with Turkish and Afghan invaders.

Languages

In the first half of the seventh century, Chinese pilgrimage Xuanzang visited the region and wrote about language, which convinced Upendranath Goswami and others that "Assamese entered into Kamarupa or western Assam where this speech was first characterised as Assamese. This is evident from the remarks of Hiuen Tsang who visited the Kingdom of Kamarupa in the first half of the seventh century A.D., during the reign of Bhaskaravarman."

Indo-Aryan languages are predominant in the region, Kamrupi and Goalpariya languages are spoken in Kamrup[16] and Goalpara regions and acts as lingua franca among various tribal groups. Bodo, Rabha, Koch are other minority languages used in tribal belts.

Music

The folk songs of Goalpara region is known as Goalpariya Lokgeet, of Kamrup region is known as Kamrupi Lokgeet. Kamrupi dance is a form of dance technique that evolved from Bhaona which is a sophisticated type of dancing.[17]

Cuisine

The food of Western Assam is homogenous to a certain extent with nearby eastern states of West Bengal and Bihar. Mustard seeds is generously used in cooking, while ginger, garlic, pepper, and onions are extensively used. Traditional utensils are made of bell metal though stainless steel is quite common in modern times.

Food of Eastern Assam has much tribal influence instead of pan-Indian, like usage of bamboo shoot both fresh and fermented.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ "The territories on the west of the river Dhansiri were to be divided into five districts: (1) North-east Rangpur of Goalpara; (2) six paraganas of Kamrup, roughly corresponding to the present district of Barpeta including Bagarberra; (3) Lower Assam with twenty parganas, mostly on the north and the nine duars on the south; (4) Central Assam comprising Naduar, Charduar and Darrang on the north, Nagaon and Raha on the south of the Brahmaputra; (5) Biswanath, from the river Bharali to Biswanath on the north together with the territory known as Morung, extending from Kaliabor to the river Dhansiri." (Banerjee 1992, p. 53)

- ↑ "By 1836 the districts assumed names which became familiar in later years: Goalpara, Kamrup, Darrang and Nagaon." (Banerjee 1992, pp. 53–54)

- ↑ Suresh Kant Sharma, Usha Sharma (2005), Discovery of North-East India:Geography, History, Culture, Religion, Politics, Sociology, Science, Education and Economy - Volume 3, p. 248, Davaka (Nowgong) and Kamarupa as separate and submissive friendly kingdoms

- ↑ Kanak Lal Barua (1933), Early history of Kāmarupa, Page 47 "in the sixth or the seventh century this kingdom of Davaka was absorbed by Kamarupa."

- ↑ "It is presumed that (Kalyanavarman) conquered Davaka, incorporating it within the kingdom of Kamarupa." (Puri 1968, p. 11)

- ↑ (Sharma 1978, p. 305) While Umachal inscription stands as an index to the spread of the Aryan culture up to the Gauhati area and the Barganga inscription speaks of the spread of the Aryan culture up to the Dabaka area, the present inscription stands as an unquestionable testimony to the spread of the Aryan culture up to the Sarupathar area of upper Assam as early as in the early part of the 5th century A.D.

- ↑ "In the Battle of Itakhuli in September 1682, the Ahom forces chased the defeated Mughals nearly one hundred kilometers back to the Manas river. The Manas then became the Ahom-Mughal boundary until the British occupation." (Richards 1995, p. 247)

- ↑ Upendranath Goswami (1970), A Study on Kāmrūpī: A Dialect of Assamese, Page iii

- ↑ Sharma, Sharma, Suresh Kant, Usha (2005). Discovery of North-East India. Mittal Publications. p. 265.

- ↑ Samiti, Kamarupa Anusandhana (1984). Readings in the history & culture of Assam. Kamarupa Anusandhana Samiti. p. 227.

- ↑ Barua, Prafulla Chandra (1967), Fragments of a lost picture, Page viii

- ↑ Goswami Upendranath (1970), A Study on Kāmrūpī: A Dialect of Assamese, p. 13

- ↑ Goswami Praphulladatta (1966), The Springtime Bihu of Assam: A Socio-cultural Study, P 25

- ↑ Bīrendranātha Datta, Nabīnacandra Śarmā, Prabin Chandra Das (1994), A Handbook of Folklore Material of North-East India, p. 158

- ↑ Śarmā Nabīnacandra (1988), Essays on the Folklore of North-eastern India, P 64

- ↑ Baruah, P. N. Dutta (2007). A contrastive analysis of the morphological aspects of Assamese and Oriya. Central Institute of Indian Languages. p. 10.

- ↑ Banerji, Projesh (1959),The folk-dance of India, Page 72

- ↑ Das Jyoti (2008), Ambrosia, from the Assamese Kitchen

Bibliography

- Banerjee, A. C. (1992), "The New Regime, 1826-31", in Barpujari, H. K., The Comprehensive History of Assam, IV, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 1–43

- Puri, Baij Nath (1968). Studies in Early History and Administration in Assam. Gauhati University.

- Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521566037. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

Further reading

- Vasu, Nagendranath (1922). The Social History of Kamarupa.

- Tripathi, Chandra Dhar (2008). Kamarupa-Kalinga-Mithila politico-cultural alignment in Eastern India : history, art, traditions. Indian Institute of Advanced Study. p. 197.

- Wilt, Verne David (1995). Kamarupa. V.D. Wilt. p. 47.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 538.

- Kapoor, Subodh (2002). Encyclopaedia of ancient Indian geography. Cosmo Publications. p. 364.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 668.

- Kapoor, Subodh (2002). The Indian encyclopaedia: biographical, historical, religious, administrative, ethnological, commercial and scientific. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 320.

- Sarkar, Ichhimuddin (1992). Aspects of historical geography of Pragjyotisha-Kamarupa (ancient Assam). Naya Prokash. p. 295.

- Deka, Phani (2007). The great Indian corridor in the east. Mittal Publications. p. 404.

- Pathak, Guptajit (2008). Assam's history and its graphics. Mittal Publications. p. 211.

- Samiti, Kamarupa Anusandhana (1984). Readings in the history & culture of Assam. Kamarupa Anusandhana Samiti. p. 227.