Inequality in post-apartheid South Africa

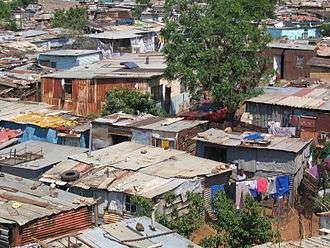

Nelson Mandela's electoral victory in 1994 signified the end of apartheid in South Africa,[1] a system of widespread racially-based segregation to enforce almost complete separation of different races in South Africa.[2] Under the apartheid system, South Africans were classified into four different races: White, Black, Coloured, and Indian/Asian,[3] with about 80% of the South African population classified as Black, 9% as White, 9% as Coloured, and 2% as Indian/Asian.[4] Under apartheid, Whites held almost all political power in South Africa, with other races almost completely marginalised from the political process. While the end of apartheid allowed equal rights for all South Africans regardless of race, modern-day South Africa struggles to correct the social inequalities created by decades of apartheid. Despite a rising GDP, indices for poverty, unemployment, income inequality, life expectancy, land ownership, have declined due to the increase in population; with the end of the apartheid system in South Africa leaving the country socio-economically stratified by race.[5] Subsequent government policies have sought to correct inequity with varying amounts of success.

Economic inequality in South Africa

Many of the inequalities created and enforced by apartheid still remain in South Africa today. Income inequality has worsened since the end of apartheid, but has become to somewhat be less associated with race, and between 1991-1996, the White middle class grew by 15% whilst the Black middle class grew by 78%.[6]

Income inequality

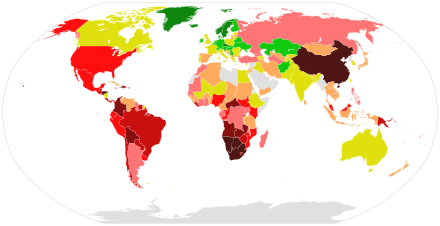

The country has one of the most unequal income distribution patterns in the world: approximately 60% of the population earns less than R42,000 per annum (about US$7,000), whereas 2.2% of the population has an income exceeding R360,000 per annum (about US$50,000). Poverty in South Africa is still largely experienced by the Black population. Despite many ANC policies aimed at closing the poverty gap, As of 2007 blacks are over-represented in poverty, making up 90% of the country's poor while at the same time, being only 79.5% of the population.[7][8]

47% of South Africans are considered impoverished by being under the national poverty line of US$43 a month[9] and the number of people living on less than US$1 a day has doubled from 2,000,000 in 1994 to 4,000,000 in 2006.[10] The remnants of apartheid-era spatial segregation of Black South Africans to impoverished rural areas is correlated with higher levels of poverty among them.[11]

Land ownership

As of 2006, 70% of South Africa's land by area was owned by Whites,[10] despite the promises of the African National Congress to redistribute significant amounts of land across racial lines to Black South Africans.[12]

Possible causes of post-apartheid inequality

Unemployment

South Africa has extremely high unemployment rates. The overall unemployment rate was 26% in 2004,[13] with unemployment being mainly concentrated amongst unskilled Blacks, who comprise 90% of the unemployed.[13][14] The ANC government pledged to reduce overall unemployment to 14% by 2014, but As of May 2009, there have not been any significant drops in unemployment.[15] One of the reasons that the unemployment rate is so high is due to the decline of the manufacturing industry.[15] The unemployment rate for Black South Africans has increased from 23% in 1991 to 48% in 2002.[16] Unemployment continues to rise, despite robust economic growth, suggesting structural factors that may be constraining the labour market.[14]

Economics

President Mandela’s adviser and successor, Thabo Mbeki, called for privatization, government spending cuts, freer trade, and looser restrictions of capital.[16] Modern South Africa relies on wealth and foreign investors to fuel its economy, spurring policies that favour these groups.[17] The ANC originally envisioned a mixed-race, socialist South Africa during the early years of its existence, and the party was banned under the Suppression of Communism Act, 1950 as a result of this. However, following the repeal of the ban forty years later and their electoral victory in 1994, their left-wing manifesto remained unpopular with businessmen, foreign politicians, and the established media.[18] For example, Mandela strongly supported nationalising banking, mining, and monopolies, but was forced to abandon this goal due to pressures from foreign investors and international economic entities like the World Bank; which instead encouraged the newly-elected South African government to promote the growth of the private sector to create jobs that would alleviate poverty.[18]

The Growth, Employment, and Redistribution report (GEAR), prepared by the Department of Finance, the Development Bank of Southern Africa, the South Africa Reserve Bank, and representatives from the World Bank, further linked economic growth rates and social objectives. In order to create a business climate attractive for foreign investors, GEAR argued that South Africa must enact neoliberal policies.[18] GEAR recommended policies that promoted globally oriented industrial growth and called for measures such as wage moderation to encourage economic growth.[18] South Africa’s unions heavily criticised GEAR, arguing that it reinforced the economic conditions of apartheid.[18]

Solutions and policies

Land reform

In 1994, the newly elected African National Congress began to develop a programme of land reform. This includes three primary means of reform: redistribution, restitution, and land tenure reform.[19] Redistribution aims to transfer White-owned commercial farms to Black South Africans.[19] Restitution involves giving compensation to land lost to Whites due to apartheid, racism, and discrimination.[19] Land tenure reform strives to provide more secure access to land.[19] Several laws have been enacted to facilitate redistribution, restitution, and land tenure reform. The Provision of Certain Land of Settlement Act of 1996 designates land for settlement purposes and ensures financial assistance to those seeking to acquire land.[19] The Restitution of Land Rights Act of 1994 guided the implementation of restitution and gave it a legal basis.[19] The Extension of Security of Tenure Act of 1996 helps rural communities obtain stronger rights to their land and regulates the relationships between owners of rural land and those living on it.[19] So far, these land reform measures have been semi-effective. By 1998, over 250,000 Black South Africans received land as a result of the Land Redistribution Programme.[19] Very few restitution claims have been resolved.[19] In the five years following the land reform programmes were instituted, only 1% of land changed hands, despite the African National Congress’s goal of 30%.[19]

The Reconstruction and Development Programme

The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) was a socio-economic programme aimed at addressing racial inequalities by creating business and employment opportunities for Blacks.[20] However, the RDP was a short-lived policy, mainly due to protest by investors and stakeholders who did not have any voice in the creation of the RDP.[20] Critics of the RDP argue that it emphasised macroeconomic stability rather than social stability.[20]

Black Economic Empowerment (BEE)

The Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment Act of 2003 aimed to offer new economic opportunities to disadvantaged communities.[20] Its goals include achieving the Constitutional right of equality, increasing broad-based participation of Blacks in the economy, protecting the common economic market, and securing equal access to government services.[20] Many scholars see BBBEE as capable of advancing economic growth, promoting new enterprises, and creating sustainable job opportunities for the previously disenfranchised.[20] Issues surrounding monitoring and enforcement are persistent obstacles to the success of BBBEE.[20] Also of note is that BEE allows the beneficiaries to come exclusively from wealthy previously disadvantaged groups. When this happens, the inequality between White and Black will improve but the inequality between rich and poor will get worse.

Education reform

South Africa's Constitution mandates that the government make education accessible to all South Africans.[21] Under apartheid, Black South Africans received only Bantu Education, whilst White South Africans received a free education of much higher quality.[21] Today, South Africa spends over 20% of its budget on education, more than any other sector.[21] Educational investment accounts for a full 7% of the GDP.[21] Since the ANC instituted widespread accessible education, the total number of years the average South African completes has increased.[22] The structure of the national educational system gives power to individual provinces to choose how their schools run, while maintaining a streamlined national curriculum.[21] This significant investment in education has slowly closed the educational gap between Black and White South Africans. Since 1994 and the end of apartheid, Black African enrollment in higher education has nearly doubled, and continues to grow faster than overall higher education growth, at about 4.4% a year.[21] Key strategies of the educational reform include: offering free meals to students during the school day, providing free schools to the poorest areas, improving teacher training programmes, standardising progress assessments, and improving school infrastructure and management.[21]

However, 27% of sixth grade students are functionally illiterate[23] while only 4% of the wealthiest students are functionally illiterate, indicating a stark divide in literacy between income quartiles.[23] The spatial segregation of apartheid continues to affect educational opportunities. Black and low-income students face geographic barriers to good schools, which are usually located in affluent neighbourhoods.[23] While South Africans enter higher education in increasing numbers, there is still a stark difference in the racial distribution of these students. Currently, about 58.5% of Whites and 51% of Indians enter some form of higher education, compared to only 14.3% of Coloureds and 12% of Blacks.[21] As of 2013, the global competitiveness survey[24] ranked South Africa last out of 148 for the quality of maths and science education and 146th out of 148 for the quality of general education, behind almost all African countries despite one of the largest budgets for education on the African continent. The same report lists the biggest obstacle to doing business as an "Inadequately educated workforce". Education, therefore, remains one of the poorest areas of performance in post-apartheid South Africa and one of the biggest causes of continued inequality and poverty.

See also

References

- ↑ U.S Department of State. "The End of Apartheid". usa.gov. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ "The World Transformed, 1945 to the Present - Paperback - Michael H. Hunt - Oxford University Press". global.oup.com. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- ↑ "Race in South Africa: Still an Issue". The Economist. 4 February 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ "South Africa's Population". southafrica.info. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ↑ "Note on Post Revolutionary Haiti, Received Wisdom and False Accounting".

- ↑ Durrheim, K (2011). "Race Trouble: Race, Identity, and Inequality in Post-Apartheid South Africa". Theory and Psychology. 22 (5).

- ↑ "United Nations report highlights growing inequality in South Africa". World Socialist Website. 21 May 2004. Retrieved 7 February 2007.

- ↑ "Mid-year population estimates, South Africa" (PDF). Statistics South Africa. 2006.

- ↑ Bhorat, H (19 July 2013). "Economic inequality is a major obstacle". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- 1 2 Klein, Naomi (2007). Democracy Born In Chains: South Africa's Constricted Freedom. Henry Holt and Company.

- ↑ Gradin, C (2013). "Race, Poverty and Deprivation in South Africa". Journal of African Economies. 22 (2): 187–238. doi:10.1093/jae/ejs019.

- ↑ Atauhene, B (2011). "South Africa's Land Reform Crisis: Eliminating the Legacy of Apartheid". Foreign Affairs. 90 (4): 121–129.

- 1 2 Akora, V.; Ricci, L.A. "Unemployment and the Labor Market" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- 1 2 "Economic Assessment of South Africa 2008: Realising South Africa's employment potential". OECD. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- 1 2 Seria, Nasreen; Cohen, Mike (5 May 2009). "South Africa's Unemployment Rate Increases to 23.5%". Bloomberg. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- 1 2 Klein, Naomi (2007). Democracy Born in Chains: South Africa's Constricting Freedom. Henry Holt and Company.

- ↑ Atuahene, B (2011). "South Africa's Land Reform Crisis: Eliminating the Legacy of Apartheid". Foreign Affairs. 90 (4): 121–129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Peet, Richard (2002). "Ideology, Discourse, and the Geography of Hegemony: From Socialist to Neoliberal Development in Postapartheid South Africa". Antipode. 34 (1): 54–84. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00226.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cliffe, Lionel (2000). "Land Reform in South Africa". Review of African Political Economy. 27 (84): 273–286. doi:10.1080/03056240008704459.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mpehle, Z (September 2011). "Black Economic Empowerment in South Africa: Reality or Illusion?". Administration Publication. 19 (3): 140–153.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Education in South Africa". southafrica.info. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2013: South Africa" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 Spaull, N (2013). "Poverty & privilege: Primary school inequality in South Africa". International Journal of Educational Development. 33 (5): 436–447. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.09.009.

- ↑ "World competitiveness survey 2013" (PDF).