Defiance Campaign

The Defiance Campaign against Unjust Laws was presented by the African National Congress (ANC) at a conference held in Bloemfontein, South Africa in December 1951.[1] The Campaign had roots in events leading up the conference. The demonstrations, taking place in 1952 were the first "large-scale, multi-racial political mobilization against apartheid laws under a common leadership."[2]

Background

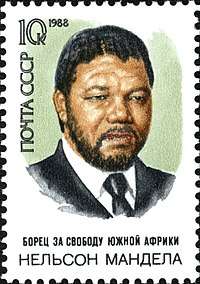

In 1948, the National Party (NP) won the election in South Africa and began to impose apartheid measures against blacks, Indians and any people of mixed race.[3] The NP restricted all political power to white people and allocated areas of South Africa for different races of people.[4] Workers, trade unionists and others spoke out on October 6, 1949 against apartheid measures and discuss a possible political strike.[3] In December of that year, leaders in the African Congress Youth League (ANCYL), such as Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo, took power.[3] The African National Congress (ANC) also "adopts the Programme of Action" on December 17, which advocated a more militant approach to protesting apartheid.[3]

In 1950, the ANC started promoting demonstrations, mass action, boycotts, strikes and acts of civil disobedience. During this time, 8,000 black people are arrested "for defying apartheid laws and regulations."[3] The South African Indian Congress (SAIC) worked in partnership with the ANC.[5] The NP used the Population Registration Act to ensure that individuals were permanently classified by race and only allowed to live in areas specified by the Group Areas Act.[3] On June 26, 1950, the National Day of Protest took place.[6] The ANC asked that people not go to work as an act of protest.[7] As a result of the protest, many people lost their jobs and the ANC set up a fund to help them.[7]

The Campaign

The Defiance Campaign was launched on the anniversary of the National Day of Protest, June 26, 1952.[3] The South African police were alerted about the action and were armed and prepared.[8] In major South African cities, people and organizations performed acts of defiance and civil disobedience.[5] The protests were largely non-violent on the parts of the participants, many of whom wore tri-color armbands signifying the ANC.[9] Black volunteers burned their pass books.[10] Other black volunteers would go into places that were considered "whites-only," which was now against the law. These volunteers were arrested, with the most arrests (over 2,000 people) being made in October 1952.[11] When protesters were arrested, they would not defend themselves in court, "leading to large-scale imprisonment."[10] Others who were offered fines as an alternative chose to go to prison.[12] The mass imprisonment, it was hoped, would overwhelm the government.[8]

The South African government viewed the protests as acts of anarchy, communism and disorder.[13] The Nationalist newspaper, the Oosterlig, wrote that the protesters "find prison a pleasant abode. These people only understand the lash."[9] Police often used batons to force protesters to submit.[9] On November 9, 1952, police fired on a group of black rioters in Kimberley killing 14 and injuring 39.[14] Other orders to shoot demonstrators "on sight" were issued by the South African Minister of Justice, Charles Swart.[15] Arrests of peaceful protestors "disgusted a section of white public opinion."[9] In July 1952, there were raids of ANC and SAIC offices.[16]

As a result of the protests, the NP started "imposing stiff penalties for protesting discriminatory laws" and then created the Public Safety Act.[2] The goals of the Defiance Campaign were not met, but the protests "demonstrated large-scale and growing opposition to apartheid."[2] The United Nations took note and called the apartheid policy a "threat to peace."[15]

In the middle of April 1953, Chief Albert Luthuli, the President-General of the ANC, proclaimed that the Defiance Campaign would be called off so that the resistance groups could reorganize taking into consideration the new political climate in South Africa.[17]

The Defiance Campaigns, including bus boycotts in South Africa, served as an inspiration to Civil Rights Activists in the United States.[18] Albert Luthuli was tried for treason, was assaulted and deposed of his chieftaincy of his Zulu clan.[11] Mandela took over the ANC after Luthuli.[19]

Defiance Campaign in Port Elizabeth

The Red Location is one of the oldest settled black townships of Port Elizabeth, Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa. It derives its name from a cluster of corrugated iron barrack buildings, which are rusted a deep red colour.[20] The Red Location consisted of three different locations namely the Gubbs Location, Coopers Kloof and Strangers Location. These locations were overcrowded and not in good condition.[21]

On 26 June 1956, Florence Matomela joined many others in a Defiance Campaign against the Apartheid pass laws at the New Brighton Railway Station. She was one of the first women arrested.

Key role players of this Defiance Campaign included:

Nosipho Dastile

Nosipho Dastile was a well known political figure and founder of the United Democratic Front. She was the first president of the Uitenhage Women’s Organisation and was the chairperson of the ANC Women’s League in Uitenhage, after the unbanning of liberation movements in the 1990s.

Nontuthuzelo Mabala

Nontuthuzelo Mabala marched against the pass laws in 1956. She was jailed at the age of 24 for six years for the role she played in the struggle against Apartheid.

Lilian Diedricks

Lillian Diedricks was born in 1925 near the railway line in Red Location, the oldest section of New Brighton township in Port Elizabeth. She was an active shop steward and founding member of the Federation of South African Women in 1954. Her family was forced out of New Brighton during the 1940s as they were classified as coloured under apartheid when the area was zoned for black people [22]

She was also one of the four women who led the Women’s March on the Union buildings to oppose the pass laws in 1956.

Diedericks was an active trade unionist, leader of South African Congress of Trade Unions and South African Communist Party member.

She was also one of the four women who led the Women’s March on the Union buildings to oppose the pass laws in 1956 along with struggle icons Rahima Moosa, Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi and Sophia Williams-De Bruyn. After a protest against the mayor of Port Elizabeth in 1956, Diedericks was arrested for treason, along with Frances Baard and Florence Matomela [23]

They were imprisoned at the Fort in Johannesburg, and acquitted in 1961.Diedericks was banned by the apartheid government, from 1967 to 1968.

The municipal house Brister House in Port Elizabeth was renamed the Lilian Diedericks Building in 2009. Lilian Diedericks lives in Gelvandale, Port Elizabeth.[23]

Veronica Sobukwe

Veronica Sobukwe (27 July 1927–15 August 2018), spouse of Robert Sobukwe, played an integral role in the Defiance Campaign. Her family was constantly harassed by the police.[24]

Zondeni Veronica Sobukwe (née Mathe) was born on July 27, 1927, in Hlobane, KwaZulu-Natal. Sobukwe was a trainee nurse at Victoria Hospital in Lovedale, Eastern Cape.[25] Victoria Hospital was established in 1898 through the Lovedale Missionary Institution and it was the first hospital in South Africa to train black nurses.[26] While Zondeni Sobukwe was a trainee, she got involved in a labour dispute with hospital management.

The dispute escalated to strike action and Sobukwe was one of the leaders, which caught the attention of Robert Sobukwe who was the president of the Student Representative Council at Fort Hare University in 1949.[27] Zondeni Sobukwe was expelled from Lovedale College the same year for her participation in the Victoria Hospital Strike. After her expulsion, the Fort Hare ANC Youth League sent Sobukwe to Johannesburg to deliver a letter to Walter Sisulu to bring to his attention the struggles of the nurses in Alice.

On 6 June 1954, she married Robert Sobukwe and they had four children, Miliswa, Dinilesizwe, Dalindyebo and Dedanizizwe. After they married she worked at Jabavu Clinic in Soweto.[28] While her husband was in prison, Zondeni unsuccessfully petitioned Jimmy Kruger and Prime Minister B.J. Vorster, demanding the release of her husband so that he could get medical treatment at home [29]

In a bid to find the truth about the cause of her husband’s death, Zondeni Sobukwe testified to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in King Williams Town on May 12, 1997.[27]

She died on the 15 August 2018 at the age of 91 years after a long illness.

Honours

The ANC's Regional Headquarters in Nelson Mandela Bay was renamed Florence Matomela House in November 2012[30] Ms Angie Motshekga, then Minister of Basic Education and President of the ANC Women's League described Florence Matomela, at the Florence Mathomela Memorial Lecture, as having battled 'triple oppression', i.e. colonial, patriarchal and class domination.[31] The Red Location Museum in New Brighton held a year-long exhibition dedicated to these women of the liberation struggle, by paying tribute to Florence Matomela, Nontuthuzelo Mabala, Veronica Sobukwe, Lilian Diedricks and Nosipho Dastile.[24]

Notable participants

References

Citations

- ↑ Lodge, Tom (1983). Black Politics in South Africa since 1945. London and New York: Longman. p. 39. ISBN 0-582-64327-9.

- 1 2 3 "The Defiance Campaign". South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid Building Democracy. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Defiance Campaign Timeline 1948-1952". South African History Online. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ "National Party (NP)". South African History Online. 30 March 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- 1 2 Phalen, Anthony (11 June 2009). "South Africans disobey apartheid laws (Defiance of Unjust Laws Campaign), 1952-1953". Global Nonviolent Action Database. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ "'Report on the National Day of Protest, June 26, 1950.' Issued by the Secretary-General of the ANC and initialed by Nelson R. Mandela, June 26, 1950". South African History Online. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- 1 2 Mandela 1990, p. 32-33.

- 1 2 "South Africa Armed Police Altered as Non-Whites Prepare Defiance Acts". Newport Daily News. 26 June 1952. Retrieved 7 September 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "'Defiance' in South Africa". The Economist. 16 August 1952. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- 1 2 Herbstein, Denis (September 1994). "The Exile Returns". Africa Report. 39 (5): 78. Retrieved 7 September 2016 – via EBSCOhost. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Okoth 2006, p. 176.

- ↑ "Cape Coloreds Choose Prison". The Age. 4 September 1952. Retrieved 7 September 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Pillay 1993, p. 16.

- ↑ "14 Africans Shot Dead in Riot". The Age. 10 November 1952. Retrieved 7 September 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Explosive Issue Before U.N." The Age. 13 November 1952. Retrieved 7 September 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Widespread Raid Across South Africa". The Ottawa Journal. 30 July 1952. Retrieved 7 September 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/defiance-campaign-1952

- ↑ Reddy, E. S. (26 June 1987). "Defiance Campaign in South Africa Recalled". O'Malley: The Heart of Hope. Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ Okoth 2006, p. 180.

- ↑ http://www.freewebs.com/redlocationmuseum/ Accessed 29 June 2017

- ↑ V Msila. A Place to Live: Red Location and its history from 1903 to 2013. AfricanSun Media.

- ↑ Reinecke, Romi. “Lillian Diedericks” Mail &. Guardian. 26 August 2016, Online

- 1 2 “60 Iconic Women — The people behind the 1956 Women's March to Pretoria (21-30)” Mail &. Guardian,25 August 2016. Online

- 1 2 B.Sands. Herald Live.Tribute to women warriors.http://www.heraldlive.co.za/the-algoa-sun/2014/01/25/tribute-to-women-warriors/ Accessed Thursday, June 29, 2017

- ↑ Ndaba, Baldwin. “Daughter of Afrika turns 90 Today”, The Star, 27 July 2017, Online.

- ↑ Victoria Hospital, Accessed 6 August 2017

- 1 2 Truth and Reconcilliation Commission: Human Rights Violations, 12 May 1997, Accessed 4 August 2017

- ↑ “Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe” Robert Sobukwe Trust.

- ↑ Sipuye, T. “Zondeni Veronica Sobukwe: 90 years of struggle, suffering and sacrifice” Pabazuka News, 27 July 2017, Online.

- ↑ http://myportelizabeth.co.za/anc-regional-office-renamed-after-stalwart-matomela/5850 Accessed 28 June 2017

- ↑ http://www.gov.za/florence-matomela-memorial-lecture--importance-1956-women's-march-ms-angie-motshekga-minister

Sources

- Mandela, Nelson (1990). The Struggle is My Life. Popular Prakashan Private Limited. ISBN 8171545238.

- Okoth, Assa (2006). A History of Africa: African Nationalism and the De-Colonisation Process, 1915-1995. East African Educational Publishers. ISBN 9966253580.

- Pillay, Gerald (1993). Voices of Liberation: Albert Lutuli. HSRC Publishers. ISBN 0796913560.

External links

- Interview of Billy Nair about the Defiance Campaign (audio)