Hendrik Verwoerd

| Hendrik Verwoerd | |

|---|---|

| |

| 6th Prime Minister of South Africa | |

|

In office 2 September 1958 – 6 September 1966 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II (1958–1961) |

| President | Charles Robberts Swart (1961–1966) |

| Governor-General |

Ernest George Jansen (1958–1959) Charles Robberts Swart (1959–1961) |

| Preceded by | Johannes Gerhardus Strijdom |

| Succeeded by |

T. E. Dönges as Acting Prime Minister |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd 8 September 1901 Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Died |

6 September 1966 (aged 64) Cape Town, South Africa |

| Nationality | South African |

| Political party | National Party |

| Spouse(s) | Betsie Schoombie |

| Children | 7 |

| Alma mater |

University of Stellenbosch University of Berlin University of Hamburg University of Leipzig |

| Occupation | Professor, politician and newspaper editor |

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd [fə'vu:rt] (8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966), also commonly referred to as H. F. Verwoerd and Dr. Verwoerd, was a South African politician, sociologist and journalist. As leader of South Africa's National Party he served as the last prime minister of the Union of South Africa from 1958 until 1961. In 1961 he proclaimed the founding of the Republic of South Africa, and continued as its prime minister from 1961 until his assassination in 1966 by Dimitri Tsafendas.

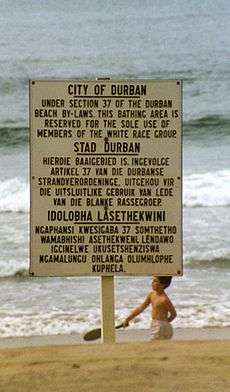

Verwoerd was an authoritarian, socially conservative leader and an Afrikaner nationalist. His goal in founding the Republic of South Africa, thereby leaving the British Commonwealth, was to preserve minority rule by white Afrikaners over the various non-white ethnic groups, including Bantu, Khoisan, Coloured and Indian people, who were the majority of South Africa's population. To that end, he greatly expanded apartheid (apart-ness or separate development), the system of forced classification and segregation by race that existed in South Africa from 1948 to 1994.

Verwoerd characterised apartheid as merely "good-neighbourliness", but its practical effects have been widely condemned, then and since, as a form of racism. Decisions that Prime Minister Verwoerd made in the areas of legislation, law enforcement and public policy caused almost the entire non-white population of South Africa to be disenfranchised, lose civil rights, and suffer discrimination.[1][2] Verwoerd heavily repressed anti-apartheid activism, ordering the detention and imprisonment of tens of thousands of people and the exile of further thousands, while greatly empowering, modernising and enlarging the security forces and army. Black-dominated political organisations such as the African National Congress (ANC) and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) were banned under Verwoerd, and ANC leaders including future President of South Africa Nelson Mandela were prosecuted for sabotage in the Rivonia Trial.[3][4]

Although apartheid existed before Verwoerd took office, his efforts to place it on a firmer legal and theoretical footing, in particular his opposition to even the limited form of integration known as baasskap (boss-ship), have led him to be dubbed the Architect of Apartheid. It was the actions of Verwoerd that prompted the United Nations in 1962 to pass Resolution 1761 condemning apartheid, which ultimately led to international isolation and economic sanctions against South Africa.

Prior to entering politics, Verwoerd was considered an exceptional student and achieved great academic success at a young age. He was appointed a professor of applied psychology at Stellenbosch University in 1927 at the age of 26, and later became head of the sociology department in 1933.

Early life

Born in the Netherlands, Verwoerd is South Africa's only foreign-born prime minister. He was the second child of Anje Strik and Wilhelmus Johannes Verwoerd; he had an elder brother named Leendert and a younger sister named Lucie. His father was a shopkeeper and a deeply religious man who decided to move his family to South Africa in 1903 because of his sympathy towards the Afrikaner nation in the wake of the Second Boer War.

Verwoerd went to a Lutheran primary school in Wynberg, a suburb of Cape Town.[5] By the end of 1912 the Verwoerd family moved to Bulawayo, in what was then Rhodesia, where his father became an assistant evangelist in the Dutch Reformed Church. Hendrik Verwoerd attended Milton High School where he was awarded the Beit Scholarship, established by diamond magnate and financier Alfred Beit. Verwoerd received the top marks for English literature in the whole of Rhodesia.[6]

In 1917 the family moved back to South Africa because the congregation in Bulawayo appointed a second minister of religion. His father took up a position in the church in Brandfort, Orange Free State. Due to the worldwide Spanish flu epidemic, the younger Verwoerd only sat for his matriculation exams in February 1919, achieving first position in the Orange Free State and fifth in South Africa.[7]

After his schooling, he proceeded to study theology at the University of Stellenbosch. He was regarded as a brilliant student and known to possess a nearly photographic memory. He was also a member of a debating club as well as a hiking club and participated in theatre productions. In 1921 he graduated with honours (BA).

He applied for admission to the Theology School. However, he was required to submit a reference from the minister of religion from his home town, Brandfort, on his suitability for such studies. Since the latter did not know him personally, but the university insisted that he should first recommend Verwoerd, Verwoerd withdrew his application for admission. He then continued to study psychology and philosophy. He was awarded a master's degree cum laude the next year. During this time he also served on the students' council together with Betsie Schoombie, later his wife, and was its president in 1923. He completed his doctorate in 1924, also cum laude. The title of his thesis was "Thought Processes and the Problem of Values"[8]

Verwoerd was awarded two scholarships for further post-doctoral studies abroad—one by the Abe Bailey Trust to study at the University of Oxford, England, and another one to continue his studies in Germany. He opted for the latter, although it was not financially as generous, because he wanted to study under a number of famous German professors of the time. Verwoerd left for Germany in 1926 and proceeded to study psychology at the universities of Hamburg, Berlin and Leipzig each for one semester. In Hamburg he studied under William Stern, in Berlin under Wolfgang Köhler and Otto Lipmann, and in Leipzig under Felix Krueger. Most of these professors were not allowed to teach anymore once the Nazis came to power in 1933. Claims that Verwoerd studied eugenics during his German sojourn[9] and later based his apartheid policy on Nazi ideology,[10] are still in the process of being evaluated by scholars. Critics contend that eugenics was usually taught at medical faculties during this period. Christoph Marx asserts that Verwoerd kept a conspicuous distance from eugenic theories and racist social technologies, emphasising environmental influences rather than hereditary abilities.[11]

Verwoerd's fiancée, Betsie Schoombie, joined him in Germany and they were married in Hamburg on 7 January 1927. Later that year, he continued his studies in the UK and then proceeded to the United States. His lecture notes and memoranda at Stellenbosch University stressed that there were no biological differences between the big racial groups, and concluded that "this was not really a factor in the development of a higher social civilisation by the Caucasians."[12]

He published a number of works dating back to his time in Germany:

- "A method for the experimental production of emotions" (1926)

- "'n Bydrae tot die metodiek en probleemstelling vir die psigologiese ondersoek van koerante-advert" ("A contribution on the psychological methodology of newspaper advertisement") (1928)

- "The distribution of 'attention' and its testing" (1928)

- "Effects of fatigue on the distribution of attention" (1928)

- "A contribution to the experimental investigation of testimony" (1929?)

- "Oor die opstel van objektiewe persoonlikheidsbepalingskemas" ("Objective criteria to determine personality types") (1930?)

- "Oor die persoonlikheid van die mens en die beskrywing daarvan" ("On the human personality and the description thereof") (1930?)

Return to South Africa

Verwoerd returned with his wife to South Africa in 1928 and was appointed to the chair of Applied Psychology and Psycho Technique at the University of Stellenbosch where, six years later, he became Professor of Sociology and Social Work. During the Great Depression, Verwoerd became active in social work among poor white South Africans. He devoted much attention to welfare work and was often consulted by welfare organisations, while he served on numerous committees. Afrikaans politics from 1910 to 1948 were divided between the "liberals" such as Jan Smuts who argued for a reconciliation with Britain vs. the "extremists" who had neither forgotten nor forgiven the British for the Boer War.[13] Both the "liberals" and the "extremists" believed that South Africa was a "white man's country", though the latter were more stridently committed to white supremacy.[14] Verwoerd belonged to the anti-British faction in Afrikaans politics who wanted to keep as much distance as possible from Britain.[15]

In 1936, Verwoerd joined by a group of Stellenbosch University professors protested against the immigration of German Jews to South Africa, who were fleeing Nazi persecution.[16] His efforts in the field of national welfare drew him into politics and in 1936 he was offered the first editorship of Die Transvaler, a position which he took up in 1937, with the added responsibility of helping to rebuild the National Party of South Africa (NP) in the Transvaal. Die Transvaler was a publication which supported the aspirations of Afrikaner nationalism, agricultural and labour rights. Combining republicanism, populism and protectionism, the paper helped "solidify the sentiments of most South Africans, that changes to the socio-economic system were vitally needed".[17] With the start of the Second World War in September 1939, Verwoerd protested against South Africa's role in the conflict when the country declared war on Germany, siding with its former colonial power, the United Kingdom.[18]

Government service

The South African general election of 1948 was held on 26 May 1948 and saw the Nationalist Party together with the Afrikaner Party winning the general elections. Malan's Herenigde Nasionale Party (HNP) concluded an election pact with the Afrikaner Party in 1947. They won the elections with a very narrow majority of five seats in Parliament, although they only got 40 percent of the voter support. This was due to the loaded constituencies in cities, which was to the advantage of rural constituencies. The nine Afrikaner Party MPs thus made it possible for Malan's HNP to form a coalition government with the Afrikaner Party of Klasie Havenga. The two parties amalgamated in 1951 as the National Party although Havenga was not comfortable with NP policy to remove coloured voters from the common voters' roll.

Running on the platform of self-determination and apartheid as it was termed for the first time, Prime Minister Daniel Malan and his party benefited from their support in the rural electorates, defeating General Jan Christiaan Smuts and his United Party. General Smuts lost his own seat of Standerton. Most party leaders agreed that the nationalist policies were responsible for the National Party's victory. To further cement their nationalist policies, Herenigde Nasionale Party leader Daniel Malan called for stricter enforcement of job reservation protecting the rights of the White working class, and the rights of White workers to organise their own labour unions outside of company control.

Hendrik Verwoerd was elected to the Senate later that year, and became the minister of native affairs under Prime Minister Malan in 1950, until his appointment as prime minister in 1958. In that position, he helped to implement the Nationalist Party's programme.[17]

Among the laws which were drawn and enacted during Verwoerd's time as minister for native affairs were the Population Registration Act and the Group Areas Act in 1950, the Pass Laws Act of 1952 and the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act of 1953. Verwoerd wrote the Bantu Education Act, which was to have a deleterious effect on the ability of black South Africans to be educated as Verwoerd himself noted that the purpose of the Bantu Education Act was to ensure that blacks would have only just enough education to work as unskilled laborers.[19] The Bantu Education Act ensured that black South Africans had only the barest minimal of education, thus entrenching the role of blacks in the apartheid economy as a cheap source of unskilled labor. In June 1954, Verwoerd in a speech stated: “The Bantu must be guided to serve his own community in all respects. There is no place for him in the European community above the level of certain forms of labour. Within his own community, however, all doors are open”.[20] One black South African woman who worked as an anti-apartheid activist, Nomavenda Mathiane, in particular criticized Verwoerd for the Bantu Education Act of 1953, which caused generations of black South Africans to suffer an inferior education, saying: “After white people had taken the land, after white people had impoverished us in South Africa, the only way out of our poverty was through education. And he came up with the idea of giving us an inferior education.”[21]

Prime minister

Prime Minister Daniel Malan announced his retirement from politics following the National Party's success in the elections of 1953. In the succession debate that followed Malan's retirement in 1954, N. C. Havenga, and J. G. Strijdom were potential successors. The Young Turks of the Transvaal got the upper hand and thus J. G. Strijdom was elected as the new leader of the National Party, who succeeded Malan as Prime Minister.

Verwoerd gradually gained popularity with the Afrikaner electorate and continued to expand his political support. With his overwhelming constituency victory in the 1958 election and the death shortly thereafter of Prime Minister J. G. Strijdom, Verwoerd was nominated together with Eben Dönges and C. R. Swart from the Free State as candidates to head the party. Verwoerd got the most votes in the second round and thus succeeded Strijdom as Prime Minister.

Apartheid

Hendrik Verwoerd is often called the "Architect of Apartheid"[22][23][24] for his role in shaping the implementation of apartheid policy when he was minister of native affairs and then prime minister. Verwoerd once described apartheid as a "policy of good neighbourliness".[25]

At the time that the NP came to power in 1948, there were factional differences in the party about the implementation of systemic racial segregation. The larger "baasskap" (white domination or supremacist) faction, favoured segregation, but also favoured the participation of black Africans in the economy as long as black labour could be controlled to advance the economic gains of Afrikaners. A second faction were the "purists", who believed in "vertical segregation", in which blacks and whites would be entirely separated, with blacks living in native reserves, with separate political and economic structures, which, they believed, would entail severe short-term pain, but would also lead to independence of white South Africa from black labour in the long-term. Verwoerd belonged to a third faction, that sympathised with the purists, but allowed for the use of black labour, while implementing the purist goal of vertical separation.[26] Verwoerd's vision of a South Africa divided into multiple ethno-states appealed to the reform-minded Afrikaner intelligensia, and it provided a more coherent philosophical and moral framework for the National Party's racist policies, while also providing a veneer of intellectual respectability to the previously crude policy of baasskap.[27][28][29]

In 1961, dismissing an Israeli vote against South African apartheid at the United Nations, Verwoerd famously said, "Israel is not consistent in its new anti-apartheid attitude ... they took Israel away from the Arabs after the Arabs lived there for a thousand years. In that, I agree with them. Israel, like South Africa, is an apartheid state."[30] According to Benjamin Pogrund, this statement was not an expression of admiration for Israel but an attempt to warn and draw support from South African Jews, whom he believed could pressure Israel to end its friendly relations with other African nations.[31] Verwoerd had previously objected to Jewish immigration to South Africa.[32]

Verwoerd felt that the political situation, that had evolved over the previous century under British rule in South Africa, called for reform.[33]

Under the Premiership of Verwoerd, the following legislative acts relating to apartheid were introduced:

- Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act (1959)

- This law laid the cornerstone for the classification of black South Africans into eight ethnic groups and their allocation to 'homelands'.[34]

- Bantu Investment Corporation Act (1959)

- A law that offered financial incentives for industrial corporations to transfer their capital from White South Africa to the Black Homelands.

- Extension of University Education Act (1959)

- Legislation putting an end to black students attending white universities and creating separate tertiary institutions for the different races.[34]

- Coloured Persons Communal Reserves Act, Act No 3 of 1961

- Preservation of Coloured Areas Act, Act No 31 of 1961

Republic

The creation of a republic was one of the National Party's long-term goals since originally coming to power in 1948.

In January 1960, Verwoerd announced that a referendum would be called to determine the republican issue, the objective being a republic within the Commonwealth. Two weeks later, Harold Macmillan, then British Prime Minister, visited South Africa. In an address to both Houses of Parliament he gave his famous Winds of Change speech, which was interpreted as an end to British support for White rule. Macmillan's "Winds of Change" speech, which implicitly criticized apartheid together with the worldwide criticism following the Sharpville massacre, created a "siege mentality" in South Africa, which Verwoerd seized upon to booster his case for a republic, presenting Elizabeth II as the ruler of a hostile power.[35] Verwoerd also ensured that South African media gave generous coverage of the breakdown of society in the Congo in the summer of 1960 following independence from Belgium as an example of the sort of "horrors" that allegedly would ensure in South Africa if apartheid was ended, which he then linked to the criticism of apartheid in Britain, arguing the Congolese "horrors" were what people in Britain were intent upon inflicting on white South Africans, fanning the flames of Anglophobia.[36]

In order to bolster support for a republic, the voting age for whites was lowered from twenty-one to eighteen, benefiting younger Afrikaans speakers, who were more likely to favour a republic, and the franchise was extended to whites in South-West Africa, most of whom were German or Afrikaans speakers. This was done even though English South Africans were slightly outnumbered by Afrikaners. The vast majority of English-South Africans were against South Africa becoming a republic and were still loyal to the British Crown.

The referendum was accepted by Parliament and was held on 5 October 1960, in which voters were asked, "Are you in favour of a Republic for the Union?" 52 percent voted 'Yes'.[37] In March 1961 at a conference of Commonwealth prime ministers in London, Verwoerd abandoned an attempt to rejoin Commonwealth which was necessary given the intention to declare a republic following a resolution jointly sponsored by Jawaharlal Nehru of India and John Diefenbaker of Canada declaring that racism was incompatible with Commonwealth membership.[38] Verwoerd abandoned the application to rejoin the Commonwealth after the Indo-Canadian resolution was accepted mostly by votes from non-white nations (Canada was the only majority white country to vote for the resolution), and stormed out of the conference.[39] For many white South Africans, especially those of British extraction, leaving the Commonwealth imposed a certain psychological sense of isolation as South Africa had left a club that it belonged to since 1910 and had been a prominent member of.[40] The Republic of South Africa came into existence on 31 May 1961, the anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging that had brought the Second Boer War to an end in 1902, and the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910. The Anglophobic Verwoerd timed the declaration of a republic with the anniversary of the Treaty of Vereeniging as a form of revenge for the defeat of the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State in the Boer War.[41] The last Governor-General, Charles Robberts Swart, took office as the first State President.

After South Africa became a republic, Verwoerd refused to accept black ambassadors from Commonwealth states.[42]

Verwoerd's overt moves to block non-whites from representing South Africa in sports—starting with cricket—started the international movement to ostracise South Africa from international sporting competition. Their last Olympic Games—until the abolition of apartheid—was in 1960, South Africa was expelled from FIFA in 1976, and whenever South African teams did participate in sports, protests and disruptions were the result. When supporters of South Africa decried their exclusion, the usual response was: "Who started it?", in reference to Verwoerd.

Assassination attempt

On 9 April 1960, Verwoerd opened the Union Exposition in Milner Park, Johannesburg, to mark the jubilee of the Union of South Africa. After Verwoerd delivered his opening address, David Pratt, a rich English businessman and farmer from the Magaliesberg, near Pretoria, attempted to assassinate Verwoerd, firing two shots from a .22 pistol at point-blank range, one bullet perforating Verwoerd's right cheek and the second his right ear.

Colonel G. M. Harrison, president of the Witwatersrand Agricultural Society, leapt up and knocked the pistol from the gunman's hand. After the pistol fell to the floor, Harrison, with the help of Major Carl Richter, the Prime Minister's personal bodyguard, civilians and another policeman overpowered the gunman. He was taken to the Marshall Square police station and later transferred to the Forensic Medical Laboratory due to his peculiar behaviour.

Within minutes of the assassination attempt, Verwoerd—still conscious and blood gushing from his face—was rushed to the nearby Johannesburg Hospital. Two days later, the hospital issued a statement which described his condition as 'indeed satisfactory—further examinations were carried out today and they confirm good expectations. Dr. Verwoerd at present is restful. There is no need for any immediate operation.' Once his condition stabilised, Verwoerd was transferred to a Pretoria Hospital. The neurologists who treated Verwoerd later stated that his escape had been 'absolutely miraculous'.[43] Specialist surgeons were called in to remove the bullets. At first, there was speculation that Verwoerd would lose his hearing and sense of balance, but this was to prove groundless. He returned to public life on 29 May, less than two months after the shooting.

David Pratt was initially held under the emergency regulations, declared on 30 March 1960, nine days after the Sharpeville massacre and shortly after Verwoerd received a death threat with a red note reading, "Today we kill Verwoerd".[44] Pratt appeared for a preliminary hearing in the Johannesburg Magistrates' Court on 20 and 21 July 1960, once it was clear that the attempt was not fatal.[45]

Pratt claimed he had been shooting 'the epitome of apartheid'. However, in his defence, he stated he only wanted to injure, not kill, Verwoerd. The court accepted the medical reports submitted to it by five different psychiatrists, all of which confirmed that Pratt lacked legal capacity and could not be held criminally liable for having shot the prime minister. On 26 September 1960, he was committed to a mental hospital in Bloemfontein. On 1 October 1961, his 53rd birthday, he committed suicide, shortly before parole was to be considered.[46]

Solidifying the system

In 1961, UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld visited South Africa where he could not reach an agreement with Prime Minister Verwoerd.[47] On 6 November 1962, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 1761, condemning South African apartheid policies. On 7 August 1963, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 181 calling for a voluntary arms embargo against South Africa, and in the same year, a Special Committee Against Apartheid was established to encourage and oversee plans of action against the authorities.[48] From 1964, the US and UK discontinued their arms trade with South Africa.[49] Economic sanctions against South Africa were also frequently debated in the UN as an effective way of putting pressure on the apartheid government. In 1962, the UN General Assembly requested that its members sever political, fiscal and transportation ties with South Africa.[50]

1966 election and assassination

The National Party under Verwoerd won the 1966 general election. During this period, the National Party government continued to foster the development of a military industrial complex, that successfully pioneered developments in native armaments manufacturing, including aircraft, small arms, armoured vehicles, and even nuclear and biological weapons.[51]

Three days before his death, Verwoerd had held talks with the Prime Minister of Lesotho, Chief Leabua Jonathan, at the Union Buildings in Pretoria.[52] Following the meeting, a joint communique was issued by the two governments with special emphasis on "co-operation without interference in each others' internal affairs".

On 6 September 1966, Verwoerd was assassinated in Cape Town, shortly after entering the House of Assembly at 14:15. A uniformed parliamentary messenger named Dimitri Tsafendas stabbed Verwoerd in the neck and chest four times before being subdued by other members of the Assembly.[53] Four members of Parliament who were also trained doctors rushed to the aid of Verwoerd and started administering cardiopulmonary resuscitation.[54] Verwoerd was rushed to Groote Schuur Hospital, but was pronounced dead upon arrival.

Tsafendas escaped the death penalty on the grounds of insanity. Judge Andries Beyers ordered Tsafendas to be imprisoned indefinitely at the "State President's pleasure"; he died aged 81 still in detention.

Verwoerd's state funeral, attended by a quarter of a million people (almost entirely white),[55] was held in Pretoria on 10 September 1966, during which his South African flag-draped casket was laid on an artillery carriage towed by a military truck. He was buried in the Heroes' Acre.[56]

The still blood-stained carpet where Verwoerd lay after his murder remained in Parliament until it was removed in 2004.[57][58]

Legacy

The town of Orania in the Northern Cape province houses the Verwoerd collection—memorabilia collected during Verwoerd’s lifetime which is now on display in the house where his widow lived for the last years before her death in 2000 at the age of 98.[59] Verwoerd's legacy in South Africa today is a controversial one as for black South Africans, Verwoerd was and still is regarded as the epitome of evil, the white supremacist who become a symbol of apartheid itself.[60] One black South African woman who worked as an anti-apartheid activist, Nomavenda Mathiane, told the American journalist Daniel Gross that "I have vivid memories of what Verwoerd did to us" and that she like almost all black South Africans felt joy at the news of his assassination.[61] One black university student, Thobeka Nkabinde, praised Tsafendas for assassinating Verwoerd, saying: "I think to some regard he [Tsanfendas] should be taken as some sort of hero. Hendrik Verwoerd was a bad person and a bad man, and his death can only by me be seen as a positive thing."[62] Most white South Africans now speak of Verwoerd as an embarrassment and only a minority still praise him.[63] Melanie Verwoerd, who was married to Verwoerd's grandson Willem, joined the African National Congress (ANC) (like her ex-husband). She recalled that bearing the surname Verwoerd always produced awkward stares in ANC circles when she introduced herself and she had to explain that she was indeed the granddaughter of the Verwoerd who was the prime minister.[64]

On the 50th anniversary of Verwoerd's assassination in 2016, the major debate within the South Africa media was whatever Tsafandas should be regarded as a hero or not, with some arguing that Tsafandas should be seen as an anti-apartheid hero while arguing against such an interpretation under the grounds that Tsfandas assassinated Verwoerd because he was mentally ill, not because he was opposed to Verwoerd's politics.[65]

Many major roads, places and facilities in cities and towns of South Africa were named after Verwoerd; in post-apartheid South Africa, there has been a campaign to take down statues of Verwoerd and rename buildings and streets named after him.[66] Famous examples include H. F. Verwoerd Airport in Port Elizabeth, renamed Port Elizabeth Airport, the Verwoerd Dam in the Free State, now the Gariep Dam, H. F. Verwoerd academic hospital in Pretoria, now Steve Biko Hospital, and the town of Verwoerdburg, now Centurion.

Gross cautioned that he felt the campaign against Verwoerd as the "architect of apartheid" was going too far in the sense that it was too convenient to blame all the wrongs and injustices of apartheid on one man who was designated as being especially evil, stating that many people were involved in creating and maintaining the apartheid system.[67] Gross concluded that blaming everything on Verwoerd was in effect excusing the actions of everyone else who supported apartheid.[68]

See also

References

- ↑ "Hendrik Verwoerd | prime minister of South Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- ↑ "Hendrik Verwoerd | prime minister of South Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- ↑ Obituary: Long-jailed assassin of South African premier in The Guardian, 11 October 1999. Retrieved on 8 July 2009. Archived 3 October 2015 at Archive.is

- ↑ "South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid". overcomingapartheid.msu.edu. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

- ↑ Grobbelaar, Pieter Willem (1967). This was a Man. Human & Rousseau. p. 13.

- ↑ Grobbelaar, Pieter Willem (1967). This was a Man. Human & Rousseau. p. 14.

- ↑ Beyers, C. J. (1981). Dictionary of South African Biography, Vol.4, Durban: Butterworth, pp. 730–40; P.W. Grobbelaar, Man van die Volk, 13–15 (1966).

- ↑ Allighan, G. (1961). Verwoerd – The End. Purnell and Sons (SA) (Pty) Ltd. p. xvi.

- ↑ Burke, A. (2006). "Mental health care during apartheid in South Africa: An illustration of how 'science' can be abused" (PDF). In Gozaydin en Madeira. Evil, law and the state. Oxford: Inter-disciplinary Press. pp. 117–133.

- ↑ Moodie, T. D. (1975). The Rise of Afrikanerdom: Power, Apartheid and the Afrikaner Civil Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-520-03943-2.

- ↑ Marx, C. (2011). "Hendrik Verwoerd's Long March to Apartheid: Nationalism and Racism in South Africa". In Berg, M.; Wendt, S. Racism in the Modern World. Oxford/New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 284–291. ISBN 978-0-85745-076-0.

- ↑ Joyce, P. (1999). A Concise Dictionary of South African Biography. Cape Town: Francolin. pp. 275–276. ISBN 1-86859-037-2.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p. 87.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p. 87.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p. 87.

- ↑ Bunting, Brian (1964). Rise of the South African Reich. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 60–63.

- 1 2 Lentz, Harris M., III (1994). Heads of States and Governments. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 451–452. ISBN 0-89950-926-6.

- ↑ Goodman, David (2002). Fault lines : journeys into the new South Africa. Weinberg, Paul. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 143. ISBN 9780520232037. OCLC 49834339.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Cole, Catherine M. (2010). Performing South Africa's Truth Commission: Stages of Transition. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 31, 226. ISBN 978-0-253-22145-2.

- ↑ Leonard, Thomas M. (2010). Encyclopedia of the Developing World. 1. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis. p. 1661. ISBN 978-0-415-97662-6.

- ↑ Coombes, Annie E. (2003). History after Apartheid: Visual Culture and Public Memory in a Democratic South Africa. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-8223-3060-1.

- ↑ "Culture, Communication and Media Studies – Freedom Square-Back to the Future". Ccms.ukzn.ac.za. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ↑ T. Kuperus (7 April 1999). State, Civil Society and Apartheid in South Africa: An Examination of Dutch Reformed Church-State Relations. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 83–. ISBN 978-0-230-37373-0.

- ↑ "Verwoerd and his policies appalled me". News24. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ "Remembering Verwoerd - OPINION | Politicsweb". www.politicsweb.co.za. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ "Afrikaner domination died with Verwoerd 50 years ago". News24. Retrieved 2018-06-19.

- ↑ The Empire's New Walls: Sovereignty, Neo-liberalism, and the Production of Space in Post-apartheid South Africa and Post-Oslo Palestine/Israel Andrew James Clarno, ProQuest, 2009. pp. 66–67

- ↑ Pogrund, Benjamin (2014-07-10). Drawing Fire: Investigating the Accusations of Apartheid in Israel. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442226845.

- ↑ Bunting, Brian (1964). Rise of the South African Reich. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 60–63.

- ↑ (Encyclopædia Britannica 1963. p. 354.)

- 1 2 "Apartheid Legislation in South Africa". Africanhistory.about.com. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p. 88.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p.92

- ↑ Osada, Masako (2002). Sanctions and honorary whites: diplomatic policies and economic realities in relations between Japan and South Africa. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 54.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p. 88.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p. 88.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p. 88.

- ↑ Brogan, Patrick (1989). The Fighting Never Stopped' Vintage Books. p. 88.

- ↑ Anthony Sampson, "His Cherubic Smile Seemed To Say, 'It's All So Simple". Life International, 3 October 1966

- ↑ Allan Bird, Bird on a wing, 205 (1992).

- ↑ "Verwoerd knew of threats but did not withdraw." The Star, 11 April 1960.

- ↑ "Aanslag: Nuwe stap met gearresteerde. Aangehou kragtens noodmaatreëls. Was nie in hof." Die Transvaler, 11 April 1960; "No news of Pratt in court." The Star, 11 April 1960; "Verwoerd saved from ordeal at the Pratt inquiry – 8 subpoenaed." Sunday Times, 10 July 1960.

- ↑ Loammi Wolf, David Beresford Pratt: die mens agter die sluipmoordpoging, LitNet Akademies, vol. 9(3), 2012 (English summary); I. Maisels, A life at law: The memoirs of I.A. Maisels, QC., 102–107 (1998).

- ↑ Feron, James (24 January 1961). UN Chief Faces Apartheid Snag; Hammarskjöld Says He Got No Accord on Race Policies During South Africa Trip. The New York Times.

- ↑ International Labour Office (1985). Special report of the Director-General on the application of the Declaration concerning the policy of "apartheid" of the Republic of South Africa, Volumes 17–22. International Labour Office.

- ↑ Johnson, Shaun (1989). South Africa: no turning back. Indiana University Press. p. 323.

- ↑ Jackson, Peter; Faupin, Mathieu (2007). The Long Road to Durban – The United Nations Role in Fighting Racism and Racial Discrimination. UN Chronicle.

- ↑ Beinart, William (2001). Twentieth-century South Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-19-289318-5.

- ↑ National University of Lesotho. Institute of Southern African Studies. Documentation and Publications Division (1966). Lesotho clippings. Documentation and Publications Division, Institute of Southern African Studies, National University of Lesotho.

- ↑ Goodman, David; Weinberg, Paul (2002). Fault lines: journeys into the new South Africa. University of California Press. p. 154.

- ↑ Havens, Murray Clark; Leiden, Carl; Schmitt, Karl Michael (1970). The politics of assassination. Prentice-Hall. p. 47.

- ↑ South Africa: Death to the Architect. TIME. 16 September 1966.

- ↑ Goodman; Weinberg (2002), p. 155.

- ↑ Leach, Graham (1986). South Africa: no easy path to peace. Routledge. p. 39.

- ↑ Pressly, Donwald (28 July 2004). "Verwoerd carpet replaced". News24.

- ↑ Betsie Verwoerd, Apartheid Ruler's Wife, 98

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gross, Daniel (14 September 2016). "How Should South Africa Remember the Architect of Apartheid?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Hendrik Verwoerd |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd. |

- H. F. Verwoerd photographed with D. F. Malan in 1954

- Video of H. Verwoerd's failed assassination in 1960

- BBC TV program on his death

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Johannes Gerhardus Strijdom |

Prime Minister of South Africa 1958–1966 |

Succeeded by Balthazar Johannes Vorster |

.svg.png)