LGBT rights in Malta

| LGBT rights in Malta | |

|---|---|

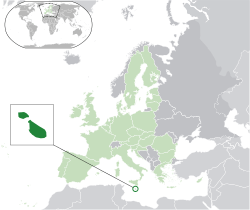

Location of Malta (dark green) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status | Legal since 1973 |

| Gender identity/expression | Transgender people can change gender with or without surgery |

| Military service | LGB allowed (1973) |

| Discrimination protections | Yes (sexual orientation and gender identity) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships |

Civil unions (2014) Same-sex marriage (2017) |

| Adoption | Yes, individuals and jointly in a civil union or marriage |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights in Malta are of the highest standards, even by comparison to other European countries, according to the United Nations.[1][2] Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the rights of the LGBT community received more awareness and same-sex sexual activity became legal in 1973, with an equal age of consent. Malta has been recognized for providing a high degree of liberty to its LGBT citizens. In October 2015, the European region of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA-Europe) ranked Malta 1st in terms of LGBT rights out of 49 observed European countries.[3][4] Malta is one of the only few countries in the world to have made LGBT rights equal at a constitutional level.[5][6] In 2016, Malta became the first country in the European Union to ban conversion therapy.[7][8]

Discrimination regarding sexual orientation and gender identity and expression has been banned nationwide since 2004. Gays, lesbians and bisexuals have been allowed to openly serve in the military since 2002. Transgender and intersex rights in Malta are of the highest standard in the world under the Gender Identity, Gender Expression And Sex Characteristics Act.[9] Same-sex marriage has been legal since 1 September 2017,[10] and prior to that civil unions (which are equal to marriage in all but name, with the same rights and obligations including joint adoption rights) were enacted in April 2014. Access to surrogacy is banned for all. A 2015 opinion poll indicated that a majority of the public supports same-sex marriage, with a significant increase over a decade.

History

Order of St. John

During the rule of the Order of St John, sodomy was considered a common practice in Malta, and generally associated with Italians and Muslims. It was common for males attracted towards other males, including knights who had to be supposedly celibate, to seek sexual favours with young looking men, identifiable effeminate males, and sometimes pederastry.[11]

Towards the 17th century, there was harsh prejudice and laws towards those who were found guilty or speak openly of being involved in same-sex activity. English voyager and author William Lithgow, writing in March 1616, says a Spanish soldier and a Maltese teenage boy were publicly burnt to ashes for confessing to have practiced sodomy together.[12] As a consequence, and fear to similar faith, about a hundred males involved in same-sex prostitution sailed to Sicily the following day. This episode, published abroad by a foreign writer, is the most detailed account of LGBT life during the rule of the Order. It represents that homosexuality was still a taboo, but a widespread practice, an open secret, and LGBT-related information was suppressed.[11]

An uncommon case, heard at the Castellania in 1774, was when an intersex person, 17-year-old Rosa Mifsud from Luqa, petitioned for a sex change by wearing as a man,[13] instead of the female clothing worn ever since born.[14] Two medical experts were appointed by the court to perform an examination.[13][14] This court case is notable as it details the use of experts in the field, similar to the late modern period.[14] The examiners were the Physician-in-Chief and a senior surgeon, both working at the Sacra Infermeria.[14] Mifsud had petitioned the Grandmaster to be recognized as a male, and it was the Grandmaster himself who took the final decision for Mifsud to wear only men clothes from then on.[13]

British period

As a British colony, Malta adopted the Penal Code of Great Britain which criminalised same-sex relations between men. There are examples of individuals caught out by the law – including a lawyer, Guglielmo Rapinett who was arrested for lewd behaviour in the 19th century while trying to seduce a guard.[15][16][17]

Homosexuality in the military was considered to be a "serious crime". Those in the military who were under investigation for homosexuality would be dismissed with immediate effect and prosecuted by a court-martial. A prominent case was that of Sub-lieutenant Christopher Swabey, who despite not found guilty, was humiliated by the British Government.[18]

In 1960, John Baptist adopted William Nathaniel Fenton, thirty years younger, when unofficially the two were in an open secret relationship. At the time adoption law did not exist, however, a law in 1971 passed prosumably so that Fenton could inherit his father-in-law Villa Francia estate in Lija. The two organized LGBT parties at the villa, and at the will of Fenton it was left as a property to the state. Today, it is an official residence for the Prime Minister of Malta.[19]

Independent Malta

Malta became independent in 1964 and at this point Malta was comparably still backwards in terms of the sexual revolution and progression in Europe.[20] Only in 1973 did the Labour Government decide to change Malta's laws to match those of Western Europe.[21]

The Malta Gay Rights Movement (MGRM), founded in 2001, is a socio-political non-governmental organisation that has as its central focus the challenges and rights of the Maltese LGBT community.[22] In February 2008, MGRM organised and presented a petition to Parliament asking for a range of measures to be introduced to protect them through the law. The petition was signed by more than 1,000 people and asked for legal recognition of same-sex couples, an anti-homophobic bullying strategy for the island nation's schools and new laws targeting homophobic and transphobic crimes. The petition received the backing of Alternattiva Demokratika. Harry Vassallo, its leader, said that the recognition of gay rights would be a step forward.[23][24]

In October 2009, George Abela, the President of Malta, met with the board of the European Region of ILGA at the presidential palace as the group prepared to open its 13th annual conference in Malta. Abela agreed that information and education were important in tackling discrimination and fostering acceptance of differences and that Malta has seen progress in LGBT acceptance. He was said that "love is the most important thing there is and it can't be 'graded' based on sexual orientation". It was the first time a head of state met with ILGA-Europe members during one of the group's annual conferences.[25]

Legality of same-sex sexual activity

Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Malta since January 1973.[26][27] The Prime Minister of Malta, Dom Mintoff, and the Labour Party legislated for the removal of the British-introduced sodomy law, at the time opposed by the Roman Catholic Church in Malta and the Maltese Nationalist Party.[28] Mikiel Gonzi, Archbishop of Malta, remained staunchly opposed to decriminalization.[29] The age of consent has been equal at 16 years of age for all since 2018.[30][31]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

Same-sex couples in Malta have the right to marry or form a civil union. The latter provides couples with exactly the same legal rights and responsibilities as a marriage, including the right to jointly adopt children.

On 28 March 2010, then Prime Minister Lawrence Gonzi announced that the Government was working on a bill to regulate cohabitation for opposite and same-sex couples. He said it was hoped the bill would be completed by the end of the year.[32][33][34] On 11 July, Gonzi confirmed that the bill would be presented in Parliament by the end of 2010.[35][36] The draft bill was presented by the Minister of Justice on 28 August 2012 and was under consultation process until 30 September.[37][38] The bill was introduced, but died in December 2012 due to the fall of the Government and expected dissolution of Parliament.[39]

Following a campaign promise during the 2013 elections, the Minister for Social Dialogue, Consumer Affairs, and Civil Liberties of the newly elected Labour Government announced that the Government was entering consultations for a bill granting civil unions to same-sex couples, with the bill presented in Parliament on 30 September 2013.[40]

The Civil Unions Bill, which gives same-sex couples rights equivalent to marriage, including the legal right to adopt children jointly, under the legal name civil union rather than marriage, was debated in October 2013[41] and approved at the third reading on 14 April 2014. President Marie Louise Coleiro Preca signed it into law on 16 April 2014.[42]

In March 2016, Prime Minister of Malta and leader of the governing Labour Party Joseph Muscat stated at an International Women's Day event he was personally in favour of legalising same-sex marriage in the country and that it was "time for a national debate" on the issue.[43] The opposition Nationalist Party leader Simon Busuttil responded by stating that though the Government was attempting to use the issue of same-sex marriage to distract from a government scandal, he could foresee no difficulty in amending Malta's civil union legislation of 2014 to legalise same-sex marriage.[43] The country's leading gay rights organisation subsequently called for a bill to be put forward opening up marriage to all couples irrespective of gender without delay.[44]

Following the June 2017 snap elections, the Labour Government presented a bill, amending Maltese marriage law, in Parliament. It would give equal rights to same-sex couple and opposite-sex couples. The bill was introduced on 24 June and passed the Parliament on 12 July, in a 66-1 vote. The law replaces all gender-specific references in Maltese laws with gender-neutral terminology. The bill was signed into law by President Marie-Louise Coleiro and went into effect on 1 September 2017.[45][46][10]

Cruise ships

Florida-based Celebrity Cruises announced on October 11, 2017 that it will perform legal same-sex marriages on its ships while in international waters following the legalization of same-sex marriage in Malta, where most of the Celebrity fleet is registered.[47][48]

Adoption and parenting

Maltese law grants adoption rights to married couples and single persons, including single LGBT individuals. Since April 2014, same-sex couples in a civil union can jointly adopt.[49][50] The first official adoption by a same-sex couple took effect on 13 July 2016.[51][52][53][54] The child had previously been turned down by over 50 couples due to the fact he has down syndrome. By February 2018, there had been 3 adoptions by same-sex couples in Malta.[55]

For an effective adoption (by a single person, couple or partner), a court ruling is required for every individual child, irrespective of the sexual orientation of any of the prospective parent or parents.[56]

Surrogacy is presently unlawful regardless of sexual orientation and IVF access for single women and lesbians will soon be allowed under recent amendments to the Embryo Protection Act 2012.[57] In 2014, the Government announced it had no intention to legalize surrogacy.[58] On 7 September 2015, Prime Minister Muscat announced that the Government would introduce a bill that would allow IVF access to female same-sex couples, among others amendments.[59] On 30 June 2017, Minister of Health Chris Fearne stated that the Government would introduce a bill to reform the Embryo Protection Act 2012 "soon".[60][61] The bill had its first reading in the Parliament on 11 April 2018.[62][63] On 23 May, the bill passed its second reading, in a 36-29 vote with 2 MPs not voting.[64][65] It passed the committee stage on 14 June.[66] On 19 June, the bill passed its third reading, in a 34-27 vote with 6 MPs not present,[67][68][69] and was signed into law by the President on 21 June 2018.[70][71] The law took effect on 1 October 2018.[72][73]

The President's Foundation for the Wellbeing of Society has taken steps to encouraging acceptance of same-sex families within mainstream society.[74]

Discrimination protections

Since 2004, Malta has a ban on anti-gay discrimination in employment, in line with European Union requirements,[24] but discrimination remained common to some extent until 2009 according to results through questionnaires carried with the participation of the LGBT community.[75] Anti-discrimination protections were expanded in June 2012.[76]

In June 2012, Parliament amended the Criminal Code to prohibit hate crimes based on sexual orientation and gender identity.[77][78][79]

On 14 April 2014, the Parliament of Malta unanimously approved a bill which amended the Constitution to add protections from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.[80] It was signed by the President on 17 April 2014.[6]

On 10 December 2015, the Government launched a public consultation on a draft of the comprehensive Equality Act, and on a bill to establish the Human Rights and Equality Commission.[81][82]

Conversion therapy

On 16 June 2015, Civil Liberties Minister Helena Dalli announced that the Government planned to introduce a bill to ban sexual orientation or gender identity conversion therapy on minors.[83] On 15 December 2015, Dalli presented the bill for its first reading in Parliament. A public consultation on the bill was launched the same day and lasted until 15 January 2016.[84][85][86][87] The bill passed its second reading and the committee stage with amendments in November 2016, by a unanimously held vote. It then moved to a third reading and was later signed by the President before going into effect.[88] The MCP (Malta Chamber of Psychologists, the MAP (Maltese Association of Psychiatry), the MACP (Malta Association for the Counselling Profession) and the MAFT & SP (Malta Association of Family Therapy and Systemic Practice) had given their full support to the bill.[8] The bill unanimously passed its final reading on 6 December. Malta thus became the first country in the European Union to prohibit the use of conversion therapy.[7][89][90]

Domestic violence

As of 2018, a bill to protect individuals from domestic violence (including LGBT people) is being discussed. The bill is opposed by one Nationalist Party MP, Edwin Vassallo, who has also opposed other LGBT rights legislation. Both the Prime Minister and the Opposition Leader are in favour of the bill, though the latter has backed a conscience vote for those who are against.[91]

Military service

Malta allows people to serve openly in the armed forces regardless of their sexual orientation. According to the Armed Forces of Malta, a number of openly gay people serve in the AFM, and the official attitude is one of "live and let live", where "a person’s postings and duties depend on their qualifications, not their sexual orientation".[92]

Health and blood donation

Primary healthcare in Malta is available freely for everyone, including LGBT people with specific protections from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. However, while pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) are available to purchase, they are considerably expensive to pay for. There are proposals to make them more available to avoid STDs, especially HIV/AIDS, among LGBT people and heterosexuals alike.[93]

Gay and bisexual men in Malta are not allowed to donate blood.[94] In May 2016, Minister for Health Chris Fearne announced that a technical committee set up in 2015 to review the ban had recently completed its report and recommended scrapping the current indefinite deferral on donations. The new policy, if implemented, would still exclude donations from men who have had sex with another man any time in the previous 12 months.[94] In September 2016, the youth wing of the Labour Party announced their support for lifting the ban.[95] There are plans to allow LGBT individuals in a stable monogamous relationship to donate blood by early 2019.[96]

Gender identity and expression

In September 2006, Joanne Cassar, a transgender woman, was denied the right to marry her partner. In 2007, a judge in Malta ordered government officials to issue her the appropriate documentation.[97] The Director of Public Registry successfully contested that ruling in May 2008. Cassar filed a constitutional application in the First Hall of the Civil Court charging a violation of her fundamental human rights. She won that case initially, but lost on appeal in 2011.[98] In April 2013, she reached a settlement with the Government that included financial compensation in addition to promised statutory changes.[99] A leader of the Nationalist Party apologised for its part in contesting Cassar's right to marry.[100]

In April 2014, Malta became the first European state to add gender identity to its Constitution as a protected category.[101]

Applicants can change their gender identity documents by simply filing an affidavit with a notary, eliminating any requirement for medical gender reassignment procedures under the Gender Identity, Gender Expression And Sex Characteristics Act.[9][102][103] In December 2016, the Act was amended to allow minors who are sixteen and over to have their gender changed without needing to file and application in court and parental approval.[104] In November 2015, the Minister of Home Affairs informed that 40 people had legally changed their gender since enactment of the law mentioned above.[105]

Sex change operations and hormone therapy are not free of charge, and are not always easily available.[106][107]

Intersex protections

In April 2015, Malta became the first country in the world to outlaw sterilisation and invasive surgery on intersex people. Also, applicants can change their gender identity documents by simply filing an affidavit with a notary, eliminating any requirement for medical gender reassignment procedures under the Gender Identity, Gender Expression And Sex Characteristics Act.[9][102][103]

The Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act, approved by Parliament in 2015, also prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex characteristics thereby protecting intersex people from discrimination.[9][108][102]

Besides male and female, Maltese passports (as well as other identity documentation, such as identity cards and residency permits) are available with an "X" sex descriptor.[109]

Living conditions and societal attitudes

Living conditions for LGBT people have become more favourable in recent years with same-sex relationships being accepted in public though some negative conditions remain. A 2015 EU-wide survey, commissioned by the Fundamental Rights Agency, showed that 54% of gay people in Malta felt comfortable holding the hand of a same-sex partner in public, though only 40% were out at their workplaces.[110]

Malta has an active LGBT community, with well attended annual gay Pride parades in Valletta. A majority of prominent political leaders in Malta appeared at the pride parade in 2016, including Prime Minister Joseph Muscat and Opposition leader Simon Busuttil.[111] There was a notable gay club in Floriana, named Tom Bar, which was the oldest in Malta. Another presently operating LGBT-friendly club is Monaliza in Valletta.[112][113][114]

In July 2007, Malta's Union of Teachers threatened to publish the details of four attempts to out gay and lesbian teachers from Roman Catholic school posts. According to the union, Church schools were under pressure from parents to fire the teachers, leading to four interventions in the past five years.[115][116]

In 2015, the donation of reading material by the Malta Gay Rights Movement, that contained the teaching of diverse families including same-sex parenting,[117] to the Education Department caused some controversy. Minister of Education Evarist Bartolo took a position not to distribute the material, questioning both directly inclusion and indirectly discrimination.[118]

Public opinion

Polls have indicated a quick and drastic shift in public opinion on LGBT rights in Malta. The 2006 Eurobarometer survey found that 18% of the population supported same-sex marriage, whereas 73% were against (63% totally against). Adoption by same-sex couples was supported by 7% and opposed by 85% (76% totally opposed).[119]

In June 2012, a poll commissioned by MaltaToday found that support for same-sex marriage had increased significantly, with 41% of the population in favour of same-sex marriage and 52% against it. The 2012 data also showed a generational gap, with only 23% of people older than 55 supporting the legalisation of same-sex marriage, while 60% of those aged 18–35 did so.[120]

The 2015 Eurobarometer found a majority of 65% in favour of same-sex marriage, with 29% against. This was the largest increase in support of any country surveyed in the Eurobarometer compared to the 2006 results.[121]

In May 2015, PlanetRomeo, an LGBT social network, published its first Gay Happiness Index (GHI). Gay men from over 120 countries were asked about how they feel about society’s view on homosexuality, how do they experience the way they are treated by other people and how satisfied are they with their lives. Malta was ranked 27th with a GHI score of 61.[122]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws concerning gender identity | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples (e.g. civil unions) | |

| Same-sex marriage | |

| Adoption by single LGBT person | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| LGB people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Third gender option | |

| Intersex minors protected from invasive surgical procedures | |

| Conversion therapy banned | |

| Access to IVF for lesbian couples | |

| Asylum protection | |

| Access to surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

Selected literature

- Drachma Parents' Group (various) (2016). Uliedna Rigal: 50 mistoqsija u tweġiba għal ġenituri ta' wlied LGBTIQ (in Maltese). Books Distributers Limited (BDL). ISBN 978-99957-63-25-1.

See also

References

- ↑ "Watch: Malta is the 'gold standard' of LGBT reform, says UN equality boss". Timesofmalta.com. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "UN equality head praises Malta as 'beacon of human rights for LGBTIQ issues' - The Malta Independent". Independent.com.mt. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Malta ranks first in European 'rainbow map' of LGBTIQ rights". MaltaToday.com.mt.

- ↑ "Country Ranking". Rainbow-europe.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ Malta among just five countries which give LGBT people equal constitutional rights, The Times of Malta

- 1 2 "AN ACT to amend the Constitution of Malta". Justiceservices.gov.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- 1 2 Benjamin, Butterworth (6 December 2016). "Malta just became the first country in Europe to ban 'gay cure' therapy". Pink News. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016.

- 1 2 "L-MCP dwar il-kriminalizzazzjoni tal-Gay Conversion Therapy". Marsa: iNews Malta. 28 November 2016. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "ILGA-Europe". Ilga-europe.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- 1 2 Pace, Yannick (12 July 2017). "Malta legalises same-sex marriage, as parliament votes in favour of marriage equality bill". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 12 July 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- 1 2 Buttigieg, Emanuel (2011). Nobility, Faith and Masculinity: The Hospitaller Knights of Malta, c.1580-c.1700. A & C Black. p. 156. ISBN 9781441102430.

- ↑ Brincat, Joseph M. (2007). "Book reviews" (PDF). Melita Historica. 14: 448.

- 1 2 3 Savona-Ventura, Charles (2015). Knight Hospitaller Medicine in Malta [1530-1798]. Lulu. p. 115. ISBN 132648222X.

- 1 2 3 4 Cassar, Paul (11 December 1954). "Change of Sex Sanctioned by a Maltese Law Court in the Eighteenth Century" (PDF). British Medical Journal. Malta University Press. 2 (4901): 1413. PMC 2080334. PMID 13209141.

- ↑ "Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History Vol.1". Books.google.com.mt.

- ↑ "Who's who in Gay and Lesbian History". Books.google.com.mt.

- ↑ Aldrich R. & Wotherspoon G., Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History, from Antiquity to WWII, Routledge, London, 2001

- ↑ "Malta-based officer court-martialled for homosexual acts". Times of Malta. 25 September 2011.

- ↑ "MaltaToday". archive.maltatoday.com.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "Malta becomes independent, 1964: A police stabbing, a grenade, and when having a gay time was cause for an advert". Maltatoday.com.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "Malta". Maltatoday.com. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Malta e Gozo". Books.google.com.mt. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Legal Study on Homophobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in Malta" (PDF). Fra.europa.eu. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- 1 2 Malta's gay group ask for equal rights, Pink News, 21 February 2008

- ↑ "Maltese President Meets with ILGA-Europe (Baltimore Gay Life - Maryland's LGBT Community Newspaper)". Baltimore Gay Life. 12 November 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "maltastar.com". maltastar.com. 6 August 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Dr Inġ. Patrick Attard: Library on Gay-Rights in Malta and Beyond: Leħen is-Sewwa 1973: Ittra Pastorali kontra d-Dekriminilazzjoni ta' l-Omosesswalità". Patrickattard.blogspot.com. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Death of a patriarch: Dom Mintoff". Maltatoday.com.mt. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Malta Gay News Library: Leħen is-Sewwa 1973: Ittra Pastorali kontra d…". Patrickattard.blogspot.co.uk. 28 April 2014. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "The Age Of Consent In Malta Has Been Lowered". Lovin Malta. April 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ↑ "Gender-Based Violence and Domestic Violence Act, 2018"" (PDF). Docs.justice.gov.mt.

- ↑ Allied Newspapers Ltd. "Government drafting law on cohabitation". Times of Malta.

- ↑ Allied Newspapers Ltd. "Cohabitation law in the works - PM". Times of Malta.

- ↑ "Feedback sought on cohabitation Bill". F1plus.timesofmalta.com. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "New cohabitation law to be presented in Parliament by end of year". Maltatoday.com.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Allied Newspapers Ltd. "Cohabitation bill to be moved by end of year - PM". Times of Malta.

- ↑ "Update 2 - Cohabitation bill recognises same-sex couples but not families, JPO to propose amendments". MaltaToday.com.mt.

- ↑ "Cohabitation Bill launched: Gay couples 'are not a family' – Chris Said". Independent.com.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Allied Newspapers Ltd. "Cohabitation among 15 Bills put on hold". Times of Malta.

- ↑ "Parliament meets today - Bill on Civil Unions tops agenda". Timesof Malta. 30 September 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ "Civil Unions law will give same sex couples same rights, duties, as married couples". timesofmalta.com. 14 October 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ↑ Camilleri, Neil (17 April 2014). "President signs 'gay marriage' Bill". Malta Independent. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- 1 2 "'I am in favour of gay marriage, time for debate on the matter' - Joseph Muscat". Times of Malta. 4 March 2016.

- ↑ "MGRM tersely welcomes declarations on introduction of gay marriage". Malta Independent. 5 March 2016.

- ↑ "L.N. 212 of 2017 Marriage Act and other Laws (Amendment) Act, 2017 (Act No. XXIII of 2017), Commencement Notice". Ministry for Justice, Culture and Local Government of Malta. 25 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ Sansone, Kurt (29 August 2017). "Same sex couples can marry as from Friday". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ Herrera, Chabeli (October 11, 2017). "Celebrity Cruises can now perform same-sex weddings in international waters". Miami Herald. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ↑ Satchell, Arlene (October 11, 2017). "Celebrity Cruises now offering legal same-sex marriages on ships sailing internationally". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ↑ Calleja, Claudia (16 January 2013). "Consensus over gay adoption welcomed". Times of Malta. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ White, Hilary (31 March 2014). "Maltese president refuses to sign bill allowing gay civil unions and expanding gay adoption". Life Site News. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ "Court gives go-ahead for adoption by gay couple in first for Malta". Timesofmalta.com. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Anon (15 July 2016). Malta’s first child adopted by a gay couple; parents appeal the public to educate others. The Malta Independent. Retrieved on 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "Family Court approves first adoption by same-sex couple". Maltatoday.com.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "Court approves first adoption by gay couple in Malta - TVM News". Tvm.com.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Government ‘began communication’ with US, Brazil, Mexico for child adoption by same-sex couples, The Malta Independent, 18 June 2018

- ↑ "Adoption Services". Fsws.gov.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "AN ACT to provide for the protection of human embryos and other ancillary matters". Justiceservices.gov.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Ltd, Allied Newspapers. "Ban on surrogacy to stay in place". Times of Malta. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ Vella, Matthew (7 September 2015). "Prime Minister 'resolute on embryo freezing'". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ "New IVF law to eliminate same-sex discrimination, Health Minister pledges". Times of Malta. 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ Pace, Yannick (30 June 2017). "Fearne: Government has mandate to update IVF law". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ Bill No. 37 - Embryo Protection (Amendment) Bill

- ↑ New bill will make IVF available to same-sex couples and single women, allow voluntary surrogacy

- ↑ Embryo Protection Bill given second reading, Opposition votes against

- ↑ IVF amendments approved at second reading stage, with Opposition voting against

- ↑ IVF law reaches last stage in parliament

- ↑ Parliament approves controversial amendments to embryo protection law

- ↑ Embryo Protection Act amendments pass through Parliament

- ↑ Parliament votes in favour of 'historic' IVF law changes amid pro-life groups' demonstration

- ↑ President signs IVF law out of respect for Malta’s democratic process and Constitution

- ↑ Act no. XXIV of 2018 – Embryo Protection (Amendment) Act, 2018

- ↑ Embryo Freezing And Gamete Donation: Malta's Laws On Assisted Reproduction Have Just Changed, And Here's What That Means

- ↑ Embryo Protection (Amendment) Act, 2018 (Act No. XXIV of 2018) - Commencement Notice

- ↑ "LGBTIQ families may discuss and receive professional advice at President's Palace". TVM News. 27 August 2018.

- ↑ Allied Newspapers Ltd. "Anti-gay graffiti sprayed on walls in man's home". Times of Malta.

- ↑ "Thumbnail". Parlament.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "ATT Nru. VIII tal-2012". Parlament.mt. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Malta: Gender identity and sexual orientation included in hate crime laws". PinkNews. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "Gay rights movement welcomes passing of hate crimes amendments". MaltaToday.com.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "Parlament Ta' Malta". Parlament.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "Towards A Robust Human Rights And Equality Framework". socialdialogue.gov.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "Ratification of Protocol 12 commits government to raise the bar on equality - Helen Dalli". MaltaToday.com.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ Diacono, Tim (16 June 2015). "Gay 'conversion therapy' could become a criminal offence". Malta Today. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ "Malta could become first country in Europe to ban 'gay cure' therapy". PinkNews. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "Public consultation launched for draft law criminalising harmful conversion therapies". MaltaToday.com.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "Parlament Ta' Malta". Parlament.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "Towards the Affirmation of Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Gender Expression Act". socialdialogue.gov.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "Malta set to ban gay conversion therapy as Bill passes final hurdle". Malta Today. 21 November 2016.

- ↑ Stack, Liam (7 December 2016). "Malta Outlaws 'Conversion Therapy,' a First in Europe". New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ↑ Henley, Jon (7 December 2016). "Malta becomes first European country to ban 'gay cure' therapy". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016.

- ↑ "Domestic violence bill opposed by PN MP Edwin Vassallo". Times of Malta. January 24, 2018.

- ↑ AFM Denies discrimination on basis of sexual orientation The Malta Independent

- ↑ "HIV treatment in Malta archaic, activist warns". Times of Malta. 17 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Ban on gay men's blood donation may be relaxed". Timesofmalta.com. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Gay men should be allowed to donate blood - Labour youths". Timesofmalta.com. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- 1 2 "Watch: Gay men will be allowed to donate blood as of next year". Times of Malta. 29 August 2018.

- ↑ "Malta transsexual given permission to marry". Pink News. 16 February 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Joanne Cassar loses transsexual marriage case". Times of Malta. 23 May 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ Borg, Annaliza (16 April 2013). "Settlement between Joanne Cassar and government signed". Malta Independent. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ Balzan, Jurgen (10 June 2013). "De Marco says PN government let transgender persons down". Malta Today. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ Dalli, Miriam (16 April 2014). "Transgender Europe applauds Malta for naming gender identity". Malta Today. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 Bill No. 70 - Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Bill Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Cec Busby. "Malta scraps surgery and setrislation measures and passes protections for intersex people". Gay News Network. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ "Bill outlawing gay conversion therapy approved". Maltatoday.com.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "40 gender changes since new law". MaltaToday.com.mt.

- ↑ European Social Charter (revised) Conclusions 2009. p. 493.

- ↑ "Why the Tiny Island of Malta Has Europe's Most Progressive Gay Rights". Time. 15 December 2016.

- ↑ "Rainbow Europe". rainbow-europe.org. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ↑ Pace, Yannick (5 September 2017). "[WATCH] Malta introduces 'X' marker on passports, ID cards and work permits". Malta Today.

- ↑ Borg, Martina (7 July 2015). "'Social attitude to LGBTIQ community must catch up to legislation' - Dalli". Malta Today. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Party leaders attend Gay Pride in Valletta". Times of Malta. 11 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Grech, Joseph (14 January 2013). "Party in the sun on Malta". Gay Star News. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ↑ Borg, Victor Paul (2002-01-07). The Rough Guide to Malta & Gozo. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781858286808.

- ↑ The Out Traveler. LPI Media. 2006-01-01.

- ↑ "MaltaToday". archive.maltatoday.com.mt. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "Malta teachers take on Roman Catholic homophobia". PinkNews.

- ↑ "Gay-themed books in schools: Children should be given choices - clinical psychologist - The Malta Independent". Independent.com.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "LGBTIQ-friendly books help children feel included, 'teach tolerance and respect'". MaltaToday.com.mt. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- ↑ "EUROBAROMETER 66 FIRST RESULTS" (PDF). TNS. European Commission. December 2006. p. 80. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ↑ Vella, Matthew (5 June 2012). "Heartening change in attitudes to put gay unions on political agenda". MaltaToday. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ↑ "Special Eurobarometer 437: discrimination in the EU in 2015" (PDF). TNS. European Commission. October 2015. p. 373. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ↑ The Gay Happiness Index. The very first worldwide country ranking, based on the input of 115,000 gay men Planetromeo.com

- ↑ "18-year-old Nigerian man granted asylum in Malta following anti-gay persecution". PinkNews. December 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Malta grants first asylum status to transgender refugee". Malta Today. January 21, 2015.