Makuria

| Kingdom of Makuria ⲇⲱⲧⲁⲩⲟ | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

c. 500–1276 1286–Late 15th/16th century | |||||||||||||

_in_the_%22Book_of_all_kingdoms%22_(C._1350).png) The flag of Makuria according to the Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms | |||||||||||||

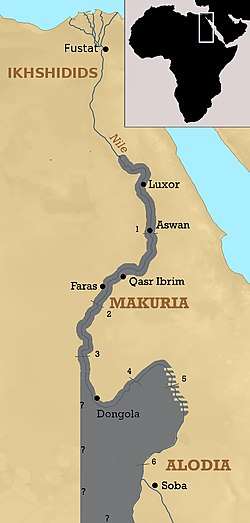

The kingdom of Makuria at its peak under king Zacharias IV (c. 962-964). | |||||||||||||

| Capital |

Dongola (until 1365) Gebel Adda (from 1365) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages |

Nubian Coptic Greek | ||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||

• fl. 651-652 | Qalidurut (first known king) | ||||||||||||

• fl. 1463-1484 | Joel (last known king) | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | c. 500 | ||||||||||||

• Makuria invaded and occupied by Mamluks | 1276-1286 | ||||||||||||

• Royal court fled to Daw (Addo), Dongola abandoned | 1365 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | Late 15th/16th century | ||||||||||||

| Currency |

Gold Solidus Dircham | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Makuria (Old Nubian: ⲇⲱⲧⲁⲩⲟ, Dotawo; Greek: Μακογρια, Makouria; Arabic: مقرة, al-Muqurra) was a Nubian kingdom located in what is today Northern Sudan and Southern Egypt. Makuria originally covered the area along the Nile River from the Third Cataract to somewhere south of Abu Hamad as well as parts of northern Kordofan. Its capital was Dongola (Arabic: Dunqulah), and the kingdom is sometimes known by the name of its capital.

By the end of the 6th century it had converted to Christianity, but in the 7th century Egypt was conquered by the Islamic armies, and Nubia was cut off from the rest of Christendom. In 651 an Arab army invaded, but it was repulsed and a treaty known as the baqt was signed creating a relative peace between the two sides that lasted until the 13th century. Makuria expanded by annexing its northern neighbour Nobatia, a process which would have occurred at some point after the Sasanian conquest of Egypt, but was completed until the reign of King Merkurios. It also maintained close dynastic ties with the kingdom of Alodia to the south. The period from the mid 8th to mid 11th century saw the kingdom stable and prosperous, in what has been called the "Golden Age".[1] Arts like wall paintings and finely crafted and decorated pottery flourished, literacy was common.

Increased aggression from Egypt, internal discord, bedouin incursions and possibly the plague and the shift of trade routes led to the state's decline in the 13th and 14th century. Due to a civil war in 1365 the kingdom was reduced to a rump state that lost much of its southern territories, including Dongola. It had disappeard by the 1560s, when the Ottoman occupied Lower Nubia. Nubia was subsequently Islamized, while the Nubians living upstream of Al Dabbah and in Kordofan were also Arabized.

Sources

Makuria is much better known than its neighbor Alodia to the south, but there are still many gaps in our knowledge. The most important source for the history of the area is various Arab travelers and historians who passed through Nubia during this period. These accounts are often problematic as many of the Arab writers were biased against their Christian neighbours and vice versa. These works generally focus on only the military conflicts between Egypt and Nubia.[2] One exception is Ibn Selim el-Aswani, an Egyptian diplomat who traveled to Dongola when Makuria was at the height of its power in the 10th century, and left a detailed account.[3]

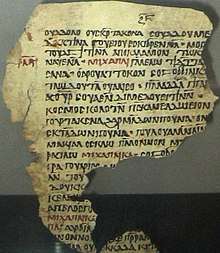

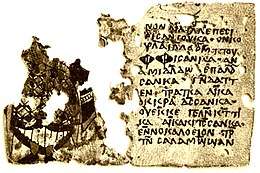

The Nubians were a literate society, and a fair body of writing survives from the period. These documents were written in the Old Nubian language in an uncial variety of the Greek alphabet extended with some Coptic symbols and some symbols unique to Nubian. Written in a language that is closely related to the modern Nobiin tongue, these documents have long been deciphered. However, the vast majority of them are works dealing with religion or legal records that are of little use to historians. The largest known collection, found at Qasr Ibrim, does contain some valuable governmental records.

The construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1964 promised to flood what had once been the northern half of Makuria. In 1960, UNESCO launched a massive effort to do as much archaeological work as possible before the flooding occurred. Thousands of experts were brought from around the world over the next few years. Some of the more important Makurian sites looked at were the city of Faras and its cathedral, excavated by a team from Poland; the British work at Qasr Ibrim; and the University of Ghana's work at the town of Debeira West, which gave important information on daily life in medieval Nubia. All of these sites are in what was Nobatia; the only major archaeological site in Makuria itself is the partial exploration of the capital at Old Dongola.[4]

History

Rise

Ptolemy mentions a Nubian people known as the Makkourae, who might be ancestors to the Makurians.[5] Considering the archaeological evidence, the Makurians probably originated from around the 4th Nile cataract, close to Napata. From there they spread downwards the Nile until they founded Dongola in around 500, making this date a plausibe terminus ante quem for the formation of the kingdom.[6] The first recorded mention of it is in a work by the 6th-century John of Ephesus, who decries its hostility to Monophysite missionaries traveling to Alodia. Soon after John of Biclarum wrote approvingly of the "Makurritae"'s[7] adoption of the rival Melkite faith.

Makuria was one of the few states in the world to repulse Muslim conquests led by the Rashidun Caliphate when they defeated an Arab army at the First Battle of Dongola in 642. The Arabs had taken Egypt in 641, and the jihad soon turned south. Makuria repeated the feat in 652 at the Second Battle of Dongola. Arab writers noted the Makurians' skill as archers in both battles. One of the few major defeats suffered by an Arab army in the first century of Islamic expansion, it led to an unprecedented agreement: the bakt. This treaty guaranteed peaceful relations between the two sides. The Nubians agreed to give Arab traders more privileges of trade in addition to a share in their slave trading, while the Egyptians may have been obliged to send manufactured goods south.[8]

At some point Makuria merged with Nobatia to the north.[9] The evidence for when this occurred is contradictory. The Arab accounts of the invasion of 652 only make reference to a single state based at Dongola. The bakt, negotiated by the Makurian king, applied to all of Nubia north of Alodia. This has led some scholars to propose that the two kingdoms were unified during this turbulent period. However, a book written in 690 makes clear that Makuria and Nobatia were still two separate and rather hostile kingdoms. Clear evidence for union is provided by an inscription from the reign of King Merkurios at Taifa that makes clear that Nobatia was under Makurian control by the middle of the 8th century. Every source after this date has Nobatia under Makurian control. This leads many scholars to infer that the unification occurred during the reign of Merkurios, who was described as the "New Constantine" by John the Deacon.[10]

What this merged kingdom should be called is unclear in both contemporary sources and among modern historians. Makuria remained in use as a geographic term for the southern half of the kingdom, but it was also used to describe the kingdom in its entirety. Some writers refer to it simply as Nubia, ignoring that southern Nubia was still under the independent kingdom of Alodia. It is also sometimes called the Kingdom of Dongola, after the capital city. Another name, the Kingdom of Makuria and Nobatia, perhaps implies a dual monarchy. Dotawo is the endonym for the kingdom, widely attested in Old Nubian materials.[11]

Zenith

Makuria seems to have been stable and prosperous during the 8th and 9th centuries. During this period Egypt was weakened by frequent civil wars, and there was thus little threat of invasion from the north. Instead it was the Nubians who intervened in the affairs of their neighbour. Much of Upper Egypt was still Christian, and it looked to the Nubian kingdoms for "protection". One report has a Nubian army sacking Cairo in the 8th century to defend the Christians, but this is probably apocryphal.[12]

Not a great deal is known about Makuria during this period. One important story is that of Zacharias III sending his son Georgios to Baghdad to negotiate a reduction of the bakt. Georgios as king also plays a prominent role in the story of Arab adventurer al-Umari. The best evidence from this time is archaeological. Excavations show that this era was one of stability and seeming prosperity. Nubian pottery, painting, and architecture all reached their heights during this era. It also seems to have been a long period of stability in the Nile floods, without the famine caused by small floods or the destruction caused by large ones.

Egypt and Makuria developed close and peaceful relations when Egypt was ruled by the Fatimids. The Shi'ite Fatimids had few allies in the Muslim world, and they turned to the southern Christians as allies.[13] Fatimid power also depended upon the slaves provided by Makuria, who were used to man the Fatimid army. Trade between the two states flourished: Egypt sent wheat, wine, and linen south while Makuria exported ivory, cattle, ostrich feathers, and slaves. Relations with Egypt soured when the Ayyubids came to power in 1171. Early in the Ayyubid period the Nubians invaded Egypt, perhaps in support of their Fatimid allies.[14] The Ayyubids repulsed their invasion and in response Salah ad-Din dispatched his brother Turan Shah to invade Nubia. He defeated the Nubians, and for several years occupied Qasr Ibrim before retreating north. The Ayyubids dispatched an emissary to Makuria to see if it was worth conquering, but he reported that the land was too poor. The Ayyubids seem to have thus largely ignored their southern neighbour for the next century.[15]

Decline

There are no records from travelers to Makuria from 1172 to 1268,[16] and the events of this period have long been a mystery, although modern discoveries have shed some light on this era. During this period Makuria seems to have entered a steep decline. The best source on this is Ibn Khaldun, writing in the 14th century, who blamed it on Bedouin invasions and Nubian intermarriage with Arabs. Other factors for the decline of Nubia might have been the change of African trade routes[17] and a severe dry period between 1150 and 1500.[18]

.jpg)

The Ayyubids dealt very aggressively with the raiding Bedouin tribes of the nearby deserts, forcing them south into conflict with the Nubians. Archaeology gives clear evidence of increasing instability in Makuria. Once unfortified cities gained city walls, the people retreated to better defended positions, such as the cliff tops at Qasr Ibrim. Houses throughout the region were built far sturdier, with secret hiding places for food and other valuables. Archaeology also shows increased signs of Arabization and Islamicization. Free trade between the kingdoms was part of the bakt, and over time Arab merchants became prominent in Dongola and other cities.

While the desert tribes may have been the most important destructive force, the campaigns of the Egyptian Mamlukes are far better documented. An important component of the bakt was the promise that Makuria would secure Egypt's southern border against raids by desert nomads, like the Beja. The Makurian state could no longer do this, prompting interventions by Egyptian armies that further weakened it. In 1272 the Mamluk Sultan Baybars invaded, after King David I had attacked the Egyptian city of Aidhab, initiating several decades of intervention by the Mamlukes in Nubian affairs.

Internal difficulties seem to have also hurt the kingdom. King David's cousin Shekanda claimed the throne and traveled to Cairo to seek the support of the Mamelukes. They agreed and took over Nubia in 1276, and placed Shekanda on the throne. The Christian Shekanda then signed an agreement making Makuria a vassal of Egypt, and a Mamluke garrison was stationed in Dongola. A few years later, Shamamun, another member of the Makurian royal family, led a rebellion against Shekanda to restore Makurian independence. He eventually defeated the Mamluk garrison and took the throne in 1286 after separating from Egypt and betraying the peace deal. He offered the Egyptians an increase in the annual baqt payments in return for scrapping the obligations to which Shekanda had agreed. The Mamluke armies were occupied elsewhere, and the Sultan of Egypt agreed to this new arrangement.

After a period of peace, king Karanbas defaulted on these payments, and the Mamluks again occupied the kingdom in 1312. This time, a Muslim member of the Makurian dynasty was placed on the throne. Sayf al-Din Abdullah Barshambu began converting the nation to Islam and in 1317 the throne hall of Dongola was turned into a mosque. This was not accepted by other Makurian leaders and the nation fell into civil war and anarchy that very year. Barshambu was eventually killed and succeeded by Kanz ad-Dawla. While ruling, his tribe, the Banu Khanz, acted a puppet dynasty of the Mamluks.[19] The already mentioned king Keranbes tried to wrestle control from Kanz ad-Dwala in 1323 and eventually seized Dongola, but was ousted just one year later. He retreated to Aswan for another chance to seize the throne, but it never came.[20]

After this episode, the history of Makuria becomes less clear. It seems that there were both Muslim and Christian kings on the Makurian throne. Both the traveller Ibn Battuta and the Egyptian historian Shihab al-Umari claim that the contemporary Makurian kings were Muslims belonging to the Banu Khanz, while the general population was Christian.[21] However, al-Umari also remarks that the throne was seized in turns by Christians and Muslims.[22] Indeed, an Ethiopian monk who travelled through Nubia in around 1330, Gadla Ewostatewos, states that the Nubian king, which he claims to have met in person, was Christian.[23] In the "Book of Knowledge of All Kingdoms", which relies on an anonymous traveller from the mid-14th century, it is claimed that the "Kingdom of Dongola" was inhabited by Christians and that its royal banner was a cross on white background (see flag).[24] Epigraphical evidence reveals the names of three Makurian kings: Siti and Abdallah Kanz ad-Dawla, both ruling during the 1330s, and Paper, who is dated to the mid 14th century.[25]

It was also in the mid 14th century, more particular after 1347, when Nubia would have been devastated by the plague. Archaeology confirms a rapid decline of the Christian Nubian civilization since then. Due to the in general rather small population the plague might have cleansed entire landscapes from its Nubian habitants.[26]

In 1365, there occurred yet another short, but disastrous civil war. The current king was killed in battle by his rebelling nephew, who had allied himself with the Banu Ja'd tribe. The brother of the murdered king and his retinue fled to a town called Daw in the Arabic sources, most likely identical with Addo in Lower Nubia.[27] The usurper then killed the nobility of the Banu Ja'd, probably because he could not trust them anymore, and destroyed and pillaged Dongola, just to travel to Daw and ask his uncle for forgiveness afterwards. Thus Dongola was left to the Banu Ja'd and Addo became the new capital.[28]

Terminal phase and further developments

The Makurian rump state

Both the usurper and the rightful heir, and most likely even the king that was killed during the usurpation, were Christian.[29] Now residing in Addo, the Makurian kings continued their Christian traditions.[30] They ruled over a reduced rump state with a confirmed north-south extension of around 100 km, albeit it might have been larger in reality.[31] Located in such a strategically irrelevant periphery, the Mamluks left the kingdom alone.[30] In the sources this kingdom appears as Dotawo. Until recently it was commonly assumed that Dotawo was, before the Makurian court shifted its seat to Addo, just a vasal kingdom of Makuria, but it is now accepted that it was merely the Old Nubian self-designation for Makuria.[32]

The last known king is Joel, who is mentioned in a 1463 document and in an inscription from 1484. Perhaps it was under Joel when the kingdom witnessed a last, brief renaissance.[33] After the death or deposition of king Joel the kingom might have collapsed.[34] The cathedral of Faras came out of use after the 15th century, just as Qasr Ibrim was abandoned by the late 15th century.[35] The palace of Addo came out of use after the 15th century as well.[31] In 1518, there is one last mention of a Nubian ruler, albeit it is unknown where he resided and if he was Christian or Muslim.[36] There were no traces of an independent Christian kingdom when the Ottomans occupied Lower Nubia in the 1560s.[34]

Further developments

Political

By the early 15th century, there is mention of a king of Dongola, most likely independent from the influence of the Egyptian sultans. Friday prayers held in Dongola failed to mention them as well.[37] These new kings of Dongola were probably confronted with waves of Arab migrations and thus were too weak to conquer the Makurian splinter state of Lower Nubia.[38]

It is possible that some petty kingdoms that continued the Christian Nubian culture developed in the former Makurian territory, like for example on Mograt island, north of Abu Hamed.[39] An other small kingdom would have been the kingdom of Kokka, founded perhaps in the 17th century in the no-mans land between the Ottoman Empire in the north and the Funj in the south. Its organization and rituals bore clear similarities to those of Christian times.[40] Eventually the kings themselves were Christians until the 18th century.[41]

In 1412, the Awlad Kenz took control of Nubia and part of Egypt above the Thebaid.

Ethnographic and linguistic

.jpg)

The Nubians upstream of Al Dabbah started to assume an Arabic identity and the Arabic language, eventually becoming the Ja'alin, claimed descendents of Abbas, uncle of prophet Muhammad.[42] The Ja'alin were already mentioned by David Reubeni, who travelled through Nubia in the early 16th century.[43] They are now divided into several sub-tribes, which are, from Al Dabbah to the conjunction of the Blue and White Nile: Shaiqiya, Rubatab, Manasir, Mirafab and the "Ja'alin proper".[44] Among them, Nubian remained a spoken language until the 19th century.[43] North of the Al Dabbah developed three Nubian sub-groups: The Kenzi, who, before the completion of the Aswan Dam, lived between Aswan and Maharraqa, the Mahasi, who settled between Maharraqa and Kerma and the Danagla, the southernmost of the remaining Nile Valley Nubians. Some count the Danagla to the Ja'alin, since the Danagla also claim to belong to that Arab tribe, but they in fact still speak a Nubian language, Dongolawi.[45] North Kordofan, which was still a part of Makuria as late as the 1330s,[46] also underwent a linguistic Arabization similar to the Nile Valley upstream of Al Dabbah. Historical and linguistic evidence confirms that the locals were predominantly Nubian-speaking until the 19th century, with a language closely related to the Nile-Nubian dialects.[47]

Today, the Nubian language is in the process of being replaced by Arabic.[48] Furthermore, the Nubians increasingly start to claim to be Arabs descending from Abbas, thus disregarding their Christian Nubian past.[49]

Economy

The main economic activity in Makuria was agriculture, with farmers growing several crops a year of barley, millet, and dates. The methods used were generally the same that had been used for millennia. Small plots of well irrigated land were lined along the banks of the Nile, which would be fertilized by the river's annual flooding. One important technological advance was the saqiya, an oxen-powered water wheel, that was introduced in the Roman period and helped increase yields and population density.[50] Settlement patterns indicate that land was divided into individual plots rather than as in a manorial system. The peasants lived in small villages composed of clustered houses of sun-dried brick.

Important industries included the production of pottery, based at Faras, and weaving based at Dongola. Smaller local industries include leatherworking, metalworking, and the widespread production of baskets, mats, and sandals from palm fibre.[51] Also important was the gold mined in the Red Sea Hills to the east of Makuria.[2]

Makurian trade was largely by barter as the state never adopted a currency. In the north, however, Egyptian coins were common. Makurian trade with Egypt was of great importance. From Egypt a wide array of luxury and manufactured goods were imported. The main Makurian export was slaves. The slaves sent north were not from Makuria itself, but rather from further south and west in Africa. Little is known about Makurian trade and relations with other parts of Africa. There is some archaeological evidence of contacts and trade with the areas to the west, especially Kordofan. Additionally, contacts to Darfur and Kanem-Bornu seem probable, but there are only few evidences. There seem to have been important political relations between Makuria and Christian Ethiopia to the south-east. For instance, in the 10th century, Georgios II successfully intervened on behalf of the unnamed ruler at that time, and persuaded Patriarch Philotheos of Alexandria to at last ordain an abuna, or metropolitan, for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. However, there is little evidence of much other interaction between the two Christian states.

Government

Makuria was a monarchy ruled by a king based in Dongola. The king was also considered a priest and could perform mass. How succession was decided is not clear. Early writers indicate it was from father to son. After the 11th century, however, it seems clear that Makuria was using the uncle-to-sister's-son system favoured for millennia in Kush. Shinnie speculates that the later form may have actually been used throughout, and that the early Arab writers merely misunderstood the situation and incorrectly described Makurian succession as similar to what they were used to.[52] A Coptic source from the mid 8th century refers to king Cyriacos as "orthodox Abyssinian king of Makuria" as well as "Greek king", with "Abyssinian" probably reflecting the Miaphysite Coptic church and "Greek" the Byzantine Orthodox one.[53] In 1186 king Moses George called himself "king of Alodia, Makuria, Nobadia, Dalmatia and Axioma".[54]

Little is known about government below the king. A wide array of officials, generally using Byzantine titles, are mentioned, but their roles are never explained. One figure who is well-known, thanks to the documents found at Qasr Ibrim, is the Eparch of Nobatia, who seems to have been the viceroy in that region after it was annexed to Makuria. The Eparch's records make clear that he was also responsible for trade and diplomacy with the Egyptians. Early records make it seem like the Eparch was appointed by the king, but later ones indicate that the position had become hereditary.[55] This office would eventually become that of the "Lord of the Horses" ruling the autonomous and then Egyptian-controlled al-Maris.

The bishops might have played a role in the governance of the state. Ibn Selim el-Aswani noted that before the king responded to his mission he met with a council of bishops.[56] El-Aswani described a highly centralized state, but other writers state that Makuria was a federation of thirteen kingdoms presided over by the great king at Dongola.[57] It is unclear what the reality was, but the Kingdom of Dotawo, prominently mentioned in the Qasr Ibrim documents, might be one of these sub-kingdoms.[58]

Religion

Paganism

One of the most debated issues among scholars is over the religion of Makuria. Up to the 5th century the old faith of Meroe seems to have remained strong, even while ancient Egyptian religion, its counterpart in Egypt, disappeared. In the 5th century the Nubians went so far as to launch an invasion of Egypt when the Christians there tried to turn some of the main temples into churches.[59]

Christianity

Archaeological evidence in this period finds a number of Christian ornaments in Nubia, and some scholars feel that this implies that conversion from below was already taking place. Others argue that it is more likely that these reflected the faith of the manufacturers in Egypt rather than the buyers in Nubia.

Certain conversion came with a series of 6th-century missions. The Byzantine Empire dispatched an official party to try to convert the kingdoms to Chalcedonian Christianity, but Empress Theodora reportedly conspired to delay the party to allow a group of Miaphysites to arrive first.[60] John of Ephesus reports that the Monophysites successfully converted the kingdoms of Nobatia and Alodia, but that Makuria remained hostile. John of Biclarum states that Makuria then embraced the rival Byzantine Christianity. Archaeological evidence seems to point to a rapid conversion brought about by an official adoption of the new faith. Millennia-old traditions such as the building of elaborate tombs, and the burying of expensive grave goods with the dead were abandoned, and temples throughout the region seem to have been converted to churches. Churches eventually were built in virtually every town and village.[2]

After this point the exact course of Makurian Christianity is much disputed. It is clear that by ca. 710 Makuria had become officially Coptic and loyal to the Coptic Patriarch of Alexandria;[61] the king of Makuria became the defender of the patriarch of Alexandria, occasionally intervening militarily to protect him, as Kyriakos did in 722. This same period saw Melkite Makuria absorb the Coptic Nobatia, and historians have long wondered why the conquering state adopted the religion of its rival. It is fairly clear that Egyptian Coptic influence was far stronger in the region, and that Byzantine power was fading, and this might have played a role. Historians are also divided on whether this was the end of the Melkite/Coptic split as there is some evidence that a Melkite minority persisted until the end of the kingdom.

Church infrastructure

The Makurian church was divided into seven bishoprics: Kalabsha, Qupta, Qasr Ibrim, Faras, Sai, Dongola, and Suenkur.[62] Unlike Ethiopia, it appears that no national church was established and all seven bishops reported directly to the Coptic Patriarch of Alexandria. The bishops were appointed by the Patriarch, not the king, though they seem to have largely been local Nubians rather than Egyptians.[63]

Monasticism

Unlike in Egypt, there is not much evidence for monasticism in Makuria. According to Adams there are only three archaeological sites that are certainly monastic. All three are fairly small and quite Coptic, leading to the possibility that they were set up by Egyptian refugees rather than indigenous Makurians.[64] Since the 10th/11th century the Nubians had an own monastery in the Egyptian Wadi El Natrun valley.[65]

Decline and rise of Islam

The end of Christianity in Makuria is unclear. Shinnie interprets the evidence from two different graveyards, in the Wadi Halfa area and at Meinarti, to conclude that Islam was present in Makuria by the early 10th century, "and it appears that Christians and Muslims must have been living in amity for some centuries." However, there is a suggestion that the Christian community was waning: the excavation of the tomb of a bishop at Qasr Ibrim recovered two rolls dated to 1372 recording his consecration in Cairo and authorizing his enthronement. Shinnie concludes this "makes it quite clear that Christianity was still of significance" although "perhaps the combining of the two under one bishop is a reflection of the dwindling of the number of Christians in the area."[66]

We are offered a glimpse of the problems the local church faced at the end from the account of the traveler Francisco Álvares. While at the court of Emperor Lebna Dengel in the 1520s, he witnessed an embassy from the Nubian Christians, who came to the Emperor asking for priests, bishops, and other personnel desperately needed to keep Christianity alive in their land. Lebna Dengel declined to help, stating that he received his bishop from the Patriarch of Alexandria, and that they too should go to him for help.[67]

.jpg)

Islamization began in what constituted the former Makurian heartland at the late 14th century, initiated by Islamic teachers arriving from the north. In Lower Nubia, Islamization would have kicked off a century later.[68] Dongola, the former capital of Makuria, was basically devoid of Christians by the end of the 16th century.[18] In the same period Muslim Mahasi Nubians and Arabized groups from the Dongola reach began settling in the Gezira, where they became a driving force of Islamization of the former Alodian heartland.[69] Isolated Christian Nubian communities lasted until the 19th, possibly even the early 20 century.[70] Clans that historically sticked longer to Christianity were discriminated and forced to pay tribute to those who had converted to Islam earlier, as they were regarded as semi-infidels.[71] The enforcement of Islam with actual violence is not attested, at least not by the Muslim Nubian rulers.[72] In the 18th century, the Ottomans, on the other side, were said to wage war against a Christian village in order to make it accept Islam.[73] Late-era churches generally show no signs of pillage and desecration,[72] except for the destruction of facial features on mural paintings, most likely because of Islamic aniconism.[74] Only a small minority of the churches were converted to mosques.[72] Christianizing rituals, however, outlived the formal conversion to Islam. For example, some Nubian mothers still "baptize" their newborn babies by dunking them in the Nile and shouting "I dunk you in the water by the dunking of John". In some villages, Christian female names like Eliisa or Maarta are still common.[75]

Culture

Christian Nubia was long considered something of a backwater, mainly because its graves were small and lacking the grave goods of previous eras.[76] Modern scholars realize that this was due to cultural reasons, and that the Makurians actually had a rich and vibrant art and culture.

Languages

Four languages were used in Makuria: Nubian, Coptic, Greek and Arabic.[77] Nubian was represented by two dialects, with Nobiin being said to have been spoken in the Nobadia province in the north and Dongolawi in the Makurian heartland,[78] although in the Islamic period Nobiin is also attested to have been employed by the Shaigiya tribe in the southeastern Dongola Reach.[79] The royal court employed Nobiin despite being located in Dongolawi-speaking territory. By the eight century Nobiin had been codified based on the Coptic alphabet,[80] but it was not until the 11th century when Nobiin had established itself as language of administrative, economic and religious documents.[81] The rise of Nobiin overlapped with the decline of the Coptic language in both Makuria and Egypt.[82] It has been suggested that before the rise of Nobiin as literary language, Coptic served as official administrative language, but this seems doubtful; Coptic literary remains are virtually absent in the Makurian heartland.[83] In Nobadia, however, Coptic was fairly wide-spread,[84] probably even serving as a lingua franca.[82] Coptic also served as the language of communication with Egypt and the Coptic Church. Coptic refugees escaping Islamic persecution settled in Makuria, while Nubian priests and bishops would have studied in Egyptian monasteries.[85] Greek, the third language, was of great prestige and used in religious context, but does not seem to have been actually spoken, making it a dead language (similar to Latin in medieval Europe).[86] Lastly, Arabic was used from the 11th and 12th centuries, superseding Coptic as language of commerce and diplomatic correspondences with Egypt. Arab traders and settlers were present in northern Nubia,[87] and Arabic documents from Qasr Ibrim confirm that they had their own communal judiciary.[88]

Arts

Painting

One of the most important discoveries of the rushed work prior to the flooding of Lower Nubia was the Cathedral of Faras. This large building had been completely filled with sand preserving a series of magnificent paintings. Similar, but less well preserved, paintings have been found at several other sites in Makuria, including palaces and private homes, giving an overall impression of Makurian art. The style and content was heavily influenced by Byzantine art, and also showed influence from Egyptian Coptic art and from Palestine.[89] Mainly religious in nature, it depicts many of the standard Christian scenes. Also illustrated are a number of Makurian kings and bishops, with noticeably darker skin than the Biblical figures.

- Gallery

Bishop Marianos with Madonna and Christ Child, Faras.

Bishop Marianos with Madonna and Christ Child, Faras. Elaborate cross, Faras.

Elaborate cross, Faras. Archangel Gabriel with sword, Faras.

Archangel Gabriel with sword, Faras._ze_%C5%9Bwi%C4%99tym_patronem._Malowid%C5%82o_%C5%9Bcienne.jpg) Eparch with bow, Faras.

Eparch with bow, Faras. A scene from the Book of Daniel showing the three youths thrown into the furnace, Faras.

A scene from the Book of Daniel showing the three youths thrown into the furnace, Faras. Group of Nubians, Faras.

Group of Nubians, Faras. Warrior saint with spear and shield, Faras.

Warrior saint with spear and shield, Faras.

Pottery

Nubian pottery in this period is also notable. Shinnie refers to it as the "richest indigenous pottery tradition on the African continent." Scholars divide the pottery into three eras.[2] The early period, from 550 to 650 according to Adams, or to 750 according to Shinnie, saw fairly simple pottery similar to that of the late Roman Empire. It also saw much of Nubian pottery imported from Egypt rather than produced domestically. Adams feels this trade ended with the invasion of 652; Shinnie links it to the collapse of Umayyad rule in 750. After this domestic production increased, with a major production facility at Faras. In this middle era, which lasted until around 1100, the pottery was painted with floral and zoomorphic scenes and showed distinct Umayyad and even Sassanian influences.[90] The late period during Makuria's decline saw domestic production again fall in favour of imports from Egypt. Pottery produced in Makuria became less ornate, but better control of firing temperatures allowed different colours of clay.

Role of women

.png)

Women enjoyed a high social standing.[91] The matrilineal succession gave the queen mother and the sister of the current king as forthcoming queen mother great political relevance.[92] This importance is attested by the fact that she constantly appears in legal documents.[93] Another female political title was the asta ("daughter"), perhaps some type of provincial representative.[91]

Women had access to education[91] and there is evidence that, like in Byzantine Egypt, female scribes existed.[94] Private land tenure was open to both men and women, meaning that both could own, buy and sell land. Transfers of land from mother to daughter were common.[95] They could also be the patrons of churches and wall paintings.[96] Inscriptions from the cathedral of Faras indicate that around every second wall painting had a female sponsor.[97]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Michalowski 1990, p. 338.

- 1 2 3 4 Shinnie 1965, p. ?.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 257.

- ↑ Godlewski 1991, p. ?.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 442.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 42-42.

- ↑ Vantini 1970, p. ?.

- ↑ Spaulding 1995, p. ?.

- ↑ Adams 1991, p. ?.

- ↑ Shinnie 1996, p. 124.

- ↑ Ruffini 2013.

- ↑ Adams 1997, p. 456.

- ↑ Kropacek 1997, p. 399.

- ↑ Kropacek 1997, p. 401.

- ↑ Lev 1999, p. 100.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 522.

- ↑ Grajetzki 2009, p. 121-122.

- 1 2 Zurawski 2014, p. 84.

- ↑ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 17.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 248.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 139-140.

- ↑ Zurawski 2014, p. 82.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 140.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 134-135.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 140-141.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 141-143.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 248-250.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 143-144.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 144.

- 1 2 Welsby 2002, p. 253.

- 1 2 Werner 2013, p. 145.

- ↑ Ruffini 2012, p. 9.

- ↑ Lajtar 2011, p. 130-131.

- 1 2 Ruffini 2012, p. 256.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 254.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 149.

- ↑ Zurawksi 2014, p. 85.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 536.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 150.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 148, 157, note 68.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, p. 256.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 557-558.

- 1 2 O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 29.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 562.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 559-560.

- ↑ Ochala 2011, p. 154.

- ↑ Hesse 2002, p. 21.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 188, note 26.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 26, note 44.

- ↑ Shinnie 1978, p. 556.

- ↑ Jakobielski 1992, p. 207.

- ↑ Shinnie 1978, p. 581.

- ↑ Greisiger & 2007 204.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 243.

- ↑ Adams 1991, p. 258.

- ↑ Jakbielski 1992, p. 211.

- ↑ Zabkar 1963, p. ?.

- ↑ Adams 1991, p. 259.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 440.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 441.

- ↑ Information on Medieval Nubia

- ↑ Shinnie 1978, p. 583.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 472.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 478.

- ↑ al-Suriany 2013, p. 257.

- ↑ Shinnie 1965, p. 265.

- ↑ Beckingham & Huntingford 1961, p. 460-462.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 155-156.

- ↑ McHugh 1994, p. 59.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 158.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 181.

- 1 2 3 Adams 1977, p. 540.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 543.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 544.

- ↑ Werner 2013, pp. 180-181.

- ↑ Adams 1977, p. 495.

- ↑ Welsby 2002, pp. 236-239.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 186.

- ↑ Bechhaus-Gerst 1996, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 187.

- ↑ Ochala 2014, p. 36.

- 1 2 Ochala 2014, p. 41.

- ↑ Ochala 2014, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Ochala 2014, p. 37.

- ↑ Werner 2013, pp. 193-194.

- ↑ Ochala 2014, pp. 43-44.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 196.

- ↑ Khan 2013, p. 147.

- ↑ Godlewski 1991, p. 255-256.

- ↑ Shinnie 1978, p. 570.

- 1 2 3 Werner 2013, p. 344.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 248.

- ↑ Ruffini 2012, p. 243.

- ↑ Ruffini 2012, pp. 237-238.

- ↑ Ruffini 2012, pp. 236-237.

- ↑ Werner 2013, p. 344-345.

- ↑ Ruffini 2012, p. 235.

References

- Adams, William Y. (1977). Nubia: Corridor to Africa. Princeton: Princeton University. ISBN 978-0-7139-0579-3.

- Adams, William Y. (1991). "The United Kingdom of Makouria and Nobadia: A Medieval Nubian Anomaly". In W.V. Davies. Egypt and Africa: Nubia from Prehistory to Islam. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-0962-6.

- al-Suriany, Bigoul (2013). "Identification of the Monastery of the Nubians in Wadi al-Natrun". In Gawdat Gabra, Hany N. Takla. Christianity and Monasticism in Aswan and Nubia. Saint Mark Foundation. pp. 257–264. ISBN 9774167643.

- (in German) Bechhaus-Gerst, Marianne (1996). Sprachwandel durch Sprachkontakt am Beispiel des Nubischen im Niltal. Köppe. ISBN 3-927620-26-2.

- Beckingham, C.F.; Huntingford, G.W.B. (1961). The Prester John of the Indies. Cambridge: Hakluyt Society.

- Godlewski, Wlodzimierz (1991). "The Birth of Nubian Art: Some Remarks". In W.V. Davies. Egypt and Africa: Nubia from Prehistory to Islam. London: British Museum. ISBN 978-0-7141-0962-6.

- Grajetzki, Wolfram (2009). "Das Ende der christlich-nubischen Reiche" (PDF). Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie. X.

- Greisiger, Lutz (2007). "Ein nubischer Erlöser-König: Kus in syrischen Apokalypsen des 7. Jahrhunderts". In Sophia G. Vashalomidze, Lutz Greisiger. Der christliche Orient und seine Umwelt (PDF).

- Hesse, Gerhard (2002). Die Jallaba und die Nuba Nordkordofans. Händler, Soziale Distinktion und Sudanisierung. Lit. ISBN 3825858901.

- Jakobielski, S (1992). "Christian Nubia at the Height of its Civilization". UNESCO General History of Africa. Volume III. University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-06698-4.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2013). "The Medieval Arabic Documents from Qasr Ibrim". Qasr Ibrim, between Egypt and Africa. Peeters. pp. 145–156.

- Kropacek, L. (1997). "Nubia from the late twelfth century to the Funj conquest in the early fifteenth century". UNESCO General History of Africa. Volume IV.

- Lev, Yaacov (1999). Saladin in Egypt. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11221-6.

- Lajtar, Adam (2011). "Qasr Ibrim's last land sale, AD 1463 (EA 90225)". Nubian Voices. Studies in Christian Nubian Culture.

- Martens-Czarnecka, Malgorzata (2015). "The Christian Nubia and the Arabs". Studia Ceranea. 5: 249–265. ISSN 2084-140X.

- McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan. Northwestern University. ISBN 0810110695.

- Michalowski, K. (1990). "The Spreading of Christianity in Nubia". UNESCO General History of Africa, Volume II. University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-06697-7.

- Ochala, Grzegorz (2011). "A King of Makuria in Kordofan". In Adam Lajtar, Jacques van der Vliet. Nubian Voices. Studies in Christian Nubian Culture. Journal of Juristic Papyrology. pp. 149–156.

- Ochala, Grzegorz (2014). "Multilingualism in Christian Nubia: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches". Dotawo: A Journal for Nubian Studies. Journal of Juristic Papyrology. 1. ISBN 0692229140.

- O'Fahey, R. S.; Spaulding, Jay (1974). Kingdoms of Sudan. Methuen Young Books.

- Ruffini, Giovanni R. (2012). Medieval Nubia. A Social and Economic History. Oxford University.

- Ruffini, Giovanni (2013). "Newer light on the Kingdom of Dotawo". In J. van der Vliet, J. L. Hagen. Qasr Ibrim, between Egypt and Africa. Studies in Cultural Exchange (NINO Symposium, Leiden, 11–12 December 2009). Peeters. pp. 179–191. ISBN 9789042930308.

- Shinnie, P.L. (1996). Ancient Nubia. London: Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7103-0517-6.

- Shinnie, P.L. (1978). "Christian Nubia.". In J.D. Fage. The Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University. pp. 556–588. ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3.

- Shinnie, P.L. (1965). "New Light on Medieval Nubia". Journal of African History. VI, 3.

- Spaulding, Jay (1995). "Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World: A Reconsideration of the Baqt Treaty". International Journal of African Historical Studies. XXVIII, 3.

- Vantini, Giovanni (1970). The Excavations at Faras.

- Welsby, Derek (2002). The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia. Pagans, Christians and Muslims along the Middle Nile. The British Museum. ISBN 0714119474.

- Werner, Roland (2013). Das Christentum in Nubien. Geschichte und Gestalt einer afrikanischen Kirche. Lit.

- Zabkar, Louis (1963). "The Eparch of Nobatia as King". Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

- Zurawski, Bogdan (2014). Kings and Pilgrims. St. Raphael Church II at Banganarti, mid-eleventh to mid-eighteenth century. IKSiO. ISBN 978-83-7543-371-5.

Further reading

- Godlweski, Wlodzimierz (2004). "The Rise of Makuria (late 5th-8th cent.)". In Timothy Kendall. Nubian Studies. 1998. Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference of Nubian Studies, August 20–26. Northeastern University. pp. 52–72. ISBN 0976122103.

- Godlweski, Wlodzimierz (2013). "Archbishop Georgios of Dongola. Socio-political change in the kingdom of Makuria in the second half of the 11th century" (PDF). Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 22: 663–677.

- Godlweski, Wlodzimierz (2013). "The Kingdom of Makuria in the 7th century. The struggle for power and survival". In Christian Julien Robin, Jérémie Schiettecatte. Les préludes de l'Islam. Ruptures et continuités. pp. 85–104. ISBN 978-2-7018-0335-7.

- Jakobielski, Stefan et al, eds. (2017). Pachoras, Faras, The wall paintings from the Cathedrals of Aetios, Paulos and Petros. ISBN 978-83-942288-7-3.

- Martens-Czarnecka, Małgorzata (2011). The Wall Paintings from the Monastery on Kom H in Dongola. ISBN 978-83-235-0923-3.

- (in French) Seignobos, Robin (2015). "Les évêches Nubiens: Nouveaux témoinages. La source de la liste de Vansleb et deux autres textes méconnus". In Adam Lajtar, Grzegorz Ochala, Jacques van der Vliet. Nubian Voices II. New Texts and Studies on Christian Nubian Culture. Raphael Taubenschlag Foundation. ISBN 8393842573. Archived from the original on 2018-09-29.

- (in French) Seignobos, Robin (2016). "La liste des conquêtes nubiennes de Baybars selon Ibn Šadd ād (1217 – 1285)". In A. Łajtar, A. Obłuski, I. Zych. Aegyptus et Nubia Christiana. The Włodzimierz Godlewski Jubilee Volume on the Occasion of his 70 th Birthday (PDF). Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeolog. pp. 553–577. ISBN 9788394228835.

- Then-Obłuska, Joanna (2017). "Royal ornaments of a late antique African kingdom, Early Makuria, Nubia (AD 450–550). Early Makuria Research Project". Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean. 26/1: 687–718.

- The Political Context of the Egyptian Gold Crisis during the Reign of Saladin

- Wozniak, Magdalena. L'influence byzantine dans l'art nubien.

- Wozniak, Magdalena. Rayonnement de Byzance: Le costume royal en Nubie (Xe s.).