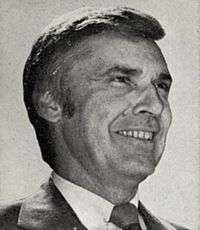

Jim Jones

| Jim Jones | |

|---|---|

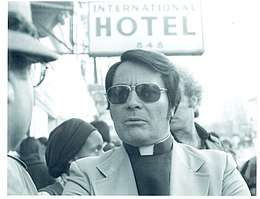

Jones at an anti-eviction protest in front of the International Hotel in 1977 | |

| Born |

James Warren Jones May 13, 1931 Crete, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died |

November 18, 1978 (aged 47) Jonestown, Guyana |

| Cause of death | Suicide by gunshot wound to the head |

| Occupation | Cult leader |

| Known for | Leader of Peoples Temple cult, Jonestown massacre |

| Spouse(s) |

Marceline Baldwin Jones (m. 1949; d. 1978) |

| Children | 9 |

James Warren Jones (May 13, 1931 – November 18, 1978) was an American religious cult leader who initiated and was responsible for a mass suicide and mass murder in Jonestown, Guyana. Jones was ordained as a Disciples of Christ pastor, and he achieved notoriety as the founder and leader of the Peoples Temple cult.

Jones started the Peoples Temple in Indiana during the 1950s. He moved the Temple to California in the mid-1960s and gained notoriety with its activities in San Francisco in the early 1970s. He then relocated to Guyana. In 1978, media reports surfaced that human rights abuses were taking place in the Peoples Temple in Jonestown. United States Congressman Leo Ryan led a delegation into the commune to investigate what was going on; Ryan and others were murdered by gunfire while boarding a return flight with defectors. Jones subsequently committed a mass murder-suicide of 918 of his followers, 304 of whom were children, almost all by cyanide poisoning via Flavor Aid. This historical episode gave rise to the American-English expression "drinking the Kool-Aid".

Early life

Jones was born on May 13, 1931 in a rural area of Crete, Indiana,[1][2] to James Thurman Jones (1887–1951), a World War I veteran, and Lynetta Putnam (1902–1977).[3][4] Jones was of Irish and Welsh descent;[5] he later claimed partial Cherokee ancestry through his mother, but his maternal second cousin later stated this was untrue.[5][note 1] Economic difficulties during the Great Depression led to the Jones family moving to the town of Lynn in 1934, where Jones grew up in a shack without plumbing.[6][7]

As a child, Jones was a voracious reader who studied Stalin, Marx, Mao, Gandhi, and Hitler carefully; noting the strengths and weaknesses of each.[8] Jones also developed an intense interest in religion, primarily because he found making friends difficult.[5] Childhood acquaintances later recalled Jones as being a "really weird kid" who was "obsessed with religion ... obsessed with death". They alleged that he frequently held funerals for small animals on his parents' property and had stabbed a cat to death.[9]

Jones and a childhood friend both claimed that his father, who was an alcoholic, was associated with the Ku Klux Klan.[7] Jones, however, came to sympathize with the country's repressed African-American community due to his own experiences as a social outcast. Jones later recounted how he and his father clashed on the issue of race, and how he did not speak with his father for "many, many years" after he refused to allow one of Jones's black friends into the house. After James and Lynetta Jones separated, Jones moved with his mother to Richmond, Indiana.[10] In December 1948 he graduated from Richmond High School early with honors.[11]

The following year, 1949, Jones married Marceline Baldwin (1927–1978), a nurse, and the couple moved to Bloomington, Indiana. She later died with him in Jonestown.[12] He attended Indiana University Bloomington, where a speech by Eleanor Roosevelt about the plight of African-Americans impressed him.[12] In 1951, Jones moved to Indianapolis, where he attended night school at Butler University, earning a degree in secondary education in 1961, ten years after enrolling.[13]

Founding of the Peoples Temple

Indiana beginnings

In 1951, Jones began attending gatherings of the Communist Party USA in Indianapolis.[14] He became flustered with harassment during the McCarthy Hearings,[14] particularly regarding an event he attended with his mother focusing on Paul Robeson, after which she was harassed by the FBI in front of her co-workers for attending.[15] He also became frustrated with ostracism of open communists in the United States, especially during the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.[16] This frustration, among other things, provoked a seminal moment for Jones in which he asked himself, "How can I demonstrate my Marxism? The thought was, infiltrate the church."[14][15]

Jones was surprised when a Methodist district superintendent helped him get a start in the church, even though he knew Jones to be a communist. Jones had not met him through the Communist Party.[16] In 1952, he became a student pastor at the Sommerset Southside Methodist Church, but later claimed he left that church because its leaders barred him from integrating blacks into his congregation.[14] Around this time, Jones witnessed a faith-healing service at a Seventh Day Baptist Church.[14] He observed that it attracted people and their money and concluded that, with financial resources from such healings, he could help accomplish his social goals.[14]

Jones organized a mammoth religious convention to take place on June 11 through June 15, 1956, in a cavernous Indianapolis hall called Cadle Tabernacle. To draw the crowds, Jones needed a religious headliner, and so he arranged to share the pulpit with Rev. William M. Branham, a healing evangelist and religious author who at the time was as highly revered as Oral Roberts.[4] Following the convention, Jones was able to launch his own church, which changed names until it became the Peoples Temple Christian Church Full Gospel.[14] The Peoples Temple was initially launched as an inter-racial mission.

Racial integrationist

In 1960, Indianapolis Mayor Charles Boswell appointed Jones director of the Human Rights Commission.[17] Jones ignored Boswell's advice to keep a low profile, finding new outlets for his views on local radio and television programs.[17] When the mayor and other commissioners asked Jones to curtail his public actions, he resisted and was wildly cheered at a meeting of the NAACP and Urban League when he yelled for his audience to be more militant, and then climaxed with, "Let my people go!"[18]

During this time, Jones also helped to racially integrate churches, restaurants, the telephone company, the police department, a theater, an amusement park, and the Methodist Hospital.[14] After swastikas were painted on the homes of two African-American families, Jones personally walked the neighborhood comforting local black people and counseling white families not to move, in order to prevent white flight.[19]

Jones set up stings to catch restaurants refusing to serve black customers[19] and wrote to American Nazi leaders and then passed their responses to the media.[20] When Jones was accidentally placed in the black ward of a hospital after a collapse in 1961, he refused to be moved; he began to make the beds and empty the bed pans of black patients. Political pressures resulting from Jones's actions caused hospital officials to desegregate the wards.[21]

Jones received considerable criticism in Indiana for his integrationist views.[14] White-owned businesses and locals were critical of him.[19] A swastika was placed on the Temple, a stick of dynamite was left in a Temple coal pile, and a dead cat was thrown at Jones's house after a threatening phone call.[20] Other incidents occurred, although some suspect that Jones himself may have been involved in at least some of them.[20]

"Rainbow Family"

Jim and Marceline Jones adopted several children of at least partly non-Caucasian ancestry; he referred to the household as his "rainbow family",[22] and stated: "Integration is a more personal thing with me now. It's a question of my son's future."[23] and also portrayed the Temple overall as a "rainbow family".

The couple adopted three children of Korean-American ancestry: Lew, Suzanne and Stephanie. Jones had been encouraging Temple members to adopt orphans from war-ravaged Korea.[24] He had also long been critical of U.S. opposition to communist leader Kim Il-Sung's 1950 invasion of South Korea, calling it the "war of liberation" and stating that "the south is a living example of all that socialism in the north has overcome".[25] In 1954, he and his wife also adopted Agnes Jones, who was partly of Native American descent.[14][23][26] Suzanne Jones was adopted at the age of six in 1959.[26] In June 1959, the couple had their only biological child, Stephan Gandhi Jones.[14]

Two years later in 1961, the Joneses became the first white couple in Indiana to adopt a black child, James Warren Jones, Jr.[27] The couple also adopted another son, who was white, named Tim.[14] Tim Jones, whose birth mother was a member of the Peoples Temple, was originally named Timothy Glen Tupper.[23]

Travel to Brazil

After a 1961 Temple speech about a nuclear apocalypse, and a January 1962 Esquire magazine article listing Belo Horizonte, Brazil, as a safe place in a nuclear war, Jones traveled with his family to the city, with the idea of setting up a new Temple location.[28] On his way to Brazil, Jones made his first trip into Guyana, then still a British colony.[29]

After arriving in Belo Horizonte, the Joneses rented a modest three-bedroom home.[30] Jones studied the local economy and receptiveness of racial minorities to his message, although language remained a barrier.[31] He also explored local Brazilian syncretic religions.[32] Jones was careful not to portray himself as a communist in a foreign territory and spoke of an apostolic communal lifestyle rather than of Castro or Marx.[33] Ultimately, the lack of resources in the locale led the Joneses to move to Rio de Janeiro in mid-1963.[34] There, they worked with the poor in Rio's slums.[34]

Jones became plagued by guilt for leaving behind the Indiana civil rights struggle and possibly losing what he had tried to build there.[34] When Jones's associate preachers in Indiana told him that the Temple was about to collapse without him, he returned.[35]

Move to California

When Jones returned from Brazil in December 1963,[36] he told his Indiana congregation that the world would be engulfed by nuclear war on July 15, 1967, that would then create a new socialist Eden on Earth, and that the Temple had to move to Northern California for safety.[14][37] Accordingly, the Temple began moving to Redwood Valley, California, near the city of Ukiah.[14]

According to religious studies professor Catherine Wessinger, while Jones always spoke of the social gospel's virtues, he chose to conceal that his gospel was actually communism until the late 1960s.[14] By that time, Jones began at least partially revealing the details of his "Apostolic Socialism" concept in Temple sermons.[14] He also taught that "those who remained drugged with the opiate of religion had to be brought to enlightenment – socialism".[38] Jones often mixed these ideas, such as preaching that, "If you're born in capitalist America, racist America, fascist America, then you're born in sin. But if you're born in socialism, you're not born in sin."[39]

By the early 1970s, Jones began deriding traditional Christianity as "fly away religion", rejecting the Bible as being a tool to oppress women and non-whites, and denouncing a "Sky God" who was no God at all.[14] Jones wrote a booklet titled "The Letter Killeth", criticizing the King James Bible.[40] Jones also began preaching that he was the reincarnation of Gandhi, Father Divine, Jesus, Gautama Buddha, and Vladimir Lenin. Former Temple member Hue Fortson, Jr. quoted Jones as saying, "What you need to believe in is what you can see ... If you see me as your friend, I'll be your friend. As you see me as your father, I'll be your father, for those of you that don't have a father ... If you see me as your savior, I'll be your savior. If you see me as your God, I'll be your God."[9]

In a 1976 phone conversation with John Maher, Jones alternately stated that he was an agnostic and an atheist.[41] Despite the Temple's fear that the IRS was investigating its religious tax exemption, Marceline Jones admitted in a 1977 New York Times interview that Jones was trying to promote Marxism in the U.S. by mobilizing people through religion, citing Mao as his inspiration.[37] She stated that, "Jim used religion to try to get some people out of the opiate of religion", and had slammed the Bible on the table yelling "I've got to destroy this paper idol!"[37] In one sermon, Jones said, "You're gonna help yourself, or you'll get no help! There's only one hope of glory; that's within you! Nobody's gonna come out of the sky! There's no heaven up there! We'll have to make heaven down here!"[9]

Focus on San Francisco

Within five years of moving to California, the Temple experienced a period of exponential growth and opened branches in cities including San Fernando, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. By the early 1970s, Jones began shifting his focus to major cities because of limited expansion opportunities in Ukiah. He eventually moved the Temple's headquarters to San Francisco, which was a major center for radical protest movements at the time. The move led Jones and the Temple to become politically influential in San Francisco politics, culminating in the Temple's instrumental role in the mayoral election victory of George Moscone in 1975. Moscone subsequently appointed Jones as the chairman of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission.[42]

Unlike most cult leaders, Jones was able to gain public support and contact with prominent politicians at the local and national level. For example, Jones and Moscone met privately with vice presidential candidate Walter Mondale on his campaign plane days before the 1976 election, leading Mondale to publicly praise the Temple.[43][44] First Lady Rosalynn Carter also personally met with Jones on multiple occasions; corresponded with him about Cuba; and spoke with him at the grand opening of the San Francisco headquarters, where he received louder applause than Mrs. Carter.[43][45][46]

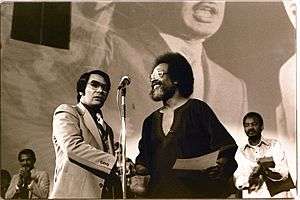

In September 1977, California assemblyman Willie Brown served as master of ceremonies at a large testimonial dinner for Jones attended by Governor Jerry Brown and Lieutenant Governor Mervyn Dymally.[47] At that dinner, Brown touted Jones as "what you should see every day when you look in the mirror in the early morning hours... a combination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Angela Davis, Albert Einstein... Chairman Mao".[48] Harvey Milk, who spoke at political rallies at the Temple,[49] wrote to Jones after one such visit: "Rev Jim, It may take me many a day to come back down from the high that I reach today. I found something dear today. I found a sense of being that makes up for all the hours and energy placed in a fight. I found what you wanted me to find. I shall be back. For I can never leave."[50][51]

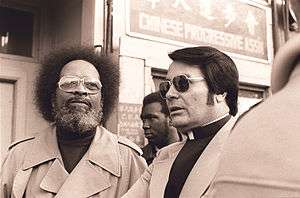

In his San Francisco apartment, Jones hosted local political figures, including Davis, for discussions.[52] He spoke with friend and San Francisco Sun-Reporter publisher Carlton Goodlett about his remorse over not being able to travel to socialist countries such as the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union, speculating that he could be Chief Dairyman of the U.S.S.R.[53] After his criticisms led to increased tensions with the Nation of Islam, Jones spoke at a huge rally healing the rift between the two groups in the Los Angeles Convention Center that was attended by many of Jones's closest political acquaintances.[54]

While Jones forged alliances with key columnists and others at the San Francisco Chronicle and other press outlets,[55] the move to San Francisco also brought increasing media scrutiny. After Chronicle reporter Marshall Kilduff encountered resistance to publishing an exposé, he brought his story to New West magazine.[56] In the summer of 1977, Jones and several hundred Temple members abruptly decided to move to the Temple's compound in Guyana after they learned of the contents of an article by Kilduff about to be published, which included allegations by former Temple members that they were physically, emotionally, and sexually abused.[46][57] Jones named the settlement "Jonestown" after himself.

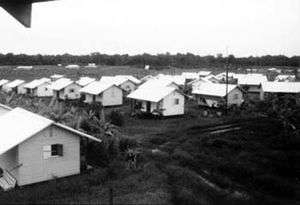

Jonestown's formation and operation

Jones had first started building Jonestown, formally known as the "Peoples Temple Agricultural Project", several years before the New West article was published. Jonestown was promoted as a means to create both a "socialist paradise" and a "sanctuary" from the media scrutiny in San Francisco.[58] Jones purported to establish Jonestown as a benevolent model communist community stating, "I believe we're the purest communists there are."[59] In that regard, like the restrictive emigration policies of the Soviet Union, Cuba, North Korea and other communist states, Jones did not permit members to leave Jonestown.[60]

Religious scholar Mary McCormick Maaga argues that Jones's authority decreased after he moved to the isolated commune, because he was not needed for recruitment and he could not hide his drug addiction from rank and file members.[61] In spite of the allegations prior to Jones's departure, the leader was still respected by some for setting up a racially mixed church which helped the disadvantaged; 68 percent of Jonestown's residents were black.[62] Jonestown was where Jones started propagating his belief in what he called "Translation", where he and his followers would all die together and move to another planet and live blissfully.[63]

New children

Jones claimed that he was the biological father of John Victor Stoen, although the birth certificate listed Temple attorney Timothy Stoen and his wife Grace as the parents of the child.[64] The Temple repeatedly claimed that Jones fathered the child when, in 1971, Stoen had requested that Jones have sex with Grace to keep her from defecting.[65] Grace defected from the Temple in 1976 and began divorce proceedings against Tim the following year. In order to avoid potentially giving up the boy in a custody dispute with Grace, Jones ordered Tim to take John to Guyana in February 1977.[66] After Tim himself defected in June 1977, the Temple kept John Stoen in Jonestown.[67]

In addition to John Stoen, Jones fathered another son, Jim Jon (Kimo), with Carolyn Louise Moore Layton, a Temple member.[68]

Pressure and waning political support

In the autumn of 1977, Tim Stoen and other Temple defectors with relatives in Jonestown formed a "Concerned Relatives" group.[69] Stoen traveled to Washington, D.C. in January 1978 to visit with State Department officials and members of Congress, and wrote a white paper detailing his grievances against Jones and the Temple.[70] Stoen's efforts aroused the curiosity of California Congressman Leo Ryan, who wrote a letter on Stoen's behalf to Guyanese Prime Minister Forbes Burnham.[71] The Concerned Relatives also began a legal battle with the Temple over the custody of Stoen's son John.[72]

While most of Jones's political allies broke ties after his departure,[73] some did not. As a show of support, Willie Brown spoke out against enemies at a rally at the Temple, which was also attended by Harvey Milk and then-Assemblyman Art Agnos.[74] On February 19, 1978, Milk wrote a letter to President Jimmy Carter defending Jones "as a man of the highest character", and claimed that Temple defectors were trying to "damage Rev. Jones' reputation" with "apparent bold-faced lies".[75] Moscone's office issued a press release saying that Jones had broken no laws.[76]

On April 11, 1978, the Concerned Relatives distributed a packet of documents, including letters and affidavits, that they titled an "Accusation of Human Rights Violations by Rev. James Warren Jones" to the Peoples Temple, members of the press, and members of Congress.[77] In June 1978, escaped Temple member Deborah Layton provided the group with a further affidavit detailing alleged crimes by the Temple and substandard living conditions in Jonestown.[78]

Jones was facing increasing scrutiny in the summer of 1978 when he hired noted JFK assassination conspiracy theorists Mark Lane and Donald Freed to help make the case of a "grand conspiracy" by U.S. intelligence agencies against the Temple. Jones told Lane he wanted to "pull an Eldridge Cleaver", referring to a fugitive Black Panther who was able to return to the U.S. after repairing his reputation.[79]

Visit by Congressman Ryan and mass suicide at Jonestown

In November 1978, Leo Ryan led a fact-finding mission to Jonestown to investigate allegations of human rights abuses.[80] His delegation included relatives of Temple members, an NBC camera crew, and reporters for various newspapers.[81] The group arrived in the Guyanese capital of Georgetown on November 15.[80] Two days later, they traveled by airplane to Port Kaituma, then were transported to the Jonestown encampment in a limousine.[82] Jones hosted a reception for the Ryan delegation that evening at the central pavilion in Jonestown.

The delegation left hurriedly the afternoon of November 18 after Temple member Don Sly attacked Ryan with a knife.[83] The attack was thwarted, bringing the visit to an abrupt end.[83] Ryan and his delegation managed to take along fifteen Temple members who had expressed a wish to leave.[84] At that time, Jones made no attempt to prevent their departure.[85]

Port Kaituma Airstrip shootings

As members of the delegation boarded two planes at the airstrip, Jones' armed guards, called the "Red Brigade," arrived on a tractor and trailer and began shooting at them.[86] The gunmen killed Ryan and four others near a Guyana Airways Twin Otter aircraft.[87] At the same time, one of the supposed defectors, Larry Layton, drew a weapon and began firing on members of the party that had already boarded a small Cessna.[88] An NBC cameraman was able to capture footage of the first few seconds of the shooting at the Otter.[87]

The five killed at the airstrip were Ryan; NBC reporter Don Harris; NBC cameraman Bob Brown; San Francisco Examiner photographer Greg Robinson; and Temple member Patricia Parks.[87] Surviving the attack were future Congresswoman Jackie Speier, then a staff member for Ryan; Richard Dwyer, the Deputy Chief of Mission from the U.S. Embassy at Georgetown; Bob Flick, a producer for NBC; Steve Sung, an NBC sound engineer; Tim Reiterman, a San Francisco Examiner reporter; Ron Javers, a San Francisco Chronicle reporter; Charles Krause, a Washington Post reporter; and several defecting Temple members.[87]

Mass murder in Jonestown

Later that same day, 909 inhabitants of Jonestown,[89] 304 of them children, died of apparent cyanide poisoning, mostly in and around the settlement's main pavilion.[90] This resulted in the greatest single loss of American civilian life in a deliberate act until the September 11 attacks.[91] The FBI later recovered a 45-minute audio recording of the suicide in progress.[92]

On that tape, Jones tells Temple members that the Soviet Union, with whom the Temple had been negotiating a potential exodus for months, would not take them after the airstrip murders.[93] The reason given by Jones to commit suicide was consistent with his previously stated conspiracy theories of intelligence organizations allegedly conspiring against the Temple, that men would "parachute in here on us", "shoot some of our innocent babies" and "they'll torture our children, they'll torture some of our people here, they'll torture our seniors".[93] Parroting Jones' prior statements that hostile forces would convert captured children to fascism, one Temple member states "the ones that they take captured, they're gonna just let them grow up and be dummies".[93]

With that reasoning, Jones and several members argued that the group should commit "revolutionary suicide" by drinking cyanide-laced grape-flavored Flavor Aid. Later-released Temple films show Jones opening a storage container full of Kool-Aid in large quantities. However, empty packets of grape Flavor Aid found on the scene show that this is what was used to mix the solution, along with a sedative.[93] One member, Christine Miller, dissents toward the beginning of the tape.[93]

When members apparently cried, Jones counseled, "Stop these hysterics. This is not the way for people who are socialists or communists to die. No way for us to die. We must die with some dignity."[93] Jones can be heard saying, "Don't be afraid to die", that death is "just stepping over into another plane" and that it's "a friend".[93] At the end of the tape, Jones concludes: "We didn't commit suicide; we committed an act of revolutionary suicide protesting the conditions of an inhumane world."[93]

According to escaping Temple members, children were given the drink first and families were told to lie down together.[94] Mass suicide had been previously discussed in simulated events called "White Nights" on a regular basis.[78][95] During at least one such prior White Night, members drank liquid that Jones falsely told them was poison.[78][95]

Death

Following the mass murder-suicide, Jones was found dead on the floor resting on a pillow near his deck chair, with a gunshot wound to his head that Guyanese coroner Cyrill Mootoo stated was consistent with a self-inflicted gunshot wound.[96] His body was later dragged outside for examination and embalming. The official autopsy conducted in December 1978 also confirms his death as a suicide. Jones's son Stephan believes his father may have directed someone else to shoot him, but that is just speculation.[97] An autopsy of Jones's body also showed levels of the barbiturate Pentobarbital which may have been lethal to humans who had not developed physiological tolerance.[98]

Sexuality

On December 13, 1973, Jones was arrested and charged with lewd conduct, masturbating in a movie theater restroom near MacArthur Park in Los Angeles that was known for homosexual activity.[99] The decoy was an undercover LAPD vice officer. Jones is on record as later telling his followers that he was "the only true heterosexual", but at least one account exists of his sexual abuse of a male member of his congregation in front of the followers, ostensibly to prove the man's own homosexual tendencies.[99]

While Jones banned sex among Temple members outside of marriage, he voraciously engaged in sexual relations with both male and female Temple members.[100][101] Jones, however, claimed that he detested engaging in homosexual activity and did so only for the male temple adherents' own good, purportedly to connect them symbolically with him (Jones).[100]

One of Jones' sources of inspiration was the controversial International Peace Mission movement leader Father Divine.[102]

Family aftermath

Marceline

On the final morning of Ryan's visit, Jones' wife Marceline took reporters on a tour of Jonestown.[103] Later in the day, she was found dead at the pavilion, having been poisoned.[104]

Surviving sons

Stephan, Jim Jr., and Tim Jones did not take part in the mass suicide because they were playing with the Peoples Temple basketball team against the Guyanese national team in Georgetown.[14][105] At the time of events in Jonestown, Stephan and Tim were both nineteen and Jim Jones Jr. was eighteen.[106] Tim's biological family, the Tuppers, which consisted of his three biological sisters,[107][108][109] biological brother,[110] and biological mother,[111] all died at Jonestown. Three days before the tragedy, Stephan Jones refused, over the radio, to comply with an order by his father to return the team to Jonestown for Ryan's visit.[112]

During the events at Jonestown, Stephan, Tim, and Jim Jones Jr. drove to the U.S. Embassy in Georgetown in an attempt to receive help. The Guyanese soldiers guarding the embassy refused to let them in after hearing about the shootings at the Port Kaituma airstrip.[113] Later, the three returned to the Temple's headquarters in Georgetown to find the bodies of Sharon Amos and her three children.[113] Guyanese soldiers kept the Jones brothers under house arrest for five days, interrogating them about the deaths in Georgetown.[113]

Stephan Jones was accused of being involved in the Georgetown deaths, and was placed in a Guyanese prison for three months.[113] Tim Jones and Johnny Cobb, another member of the Peoples Temple basketball team, were asked to go to Jonestown and help identify the bodies of people who had died.[113] After returning to the United States, Jim Jones Jr. was placed under police surveillance for several months while he lived with his older sister, Suzanne, who had previously turned against the Temple.[113]

When Jonestown was first being established, Stephan had originally avoided two attempts by his father to relocate to the settlement. He eventually moved to Jonestown after a third and final attempt. He has since said that he gave in to his father's wishes to move to Jonestown because of his mother.[115] Stephan Jones is now a businessman, and married with three daughters. He appeared in the documentary Jonestown: Paradise Lost which aired on the History Channel and Discovery Channel. He stated he will not watch the documentary and has never grieved for his father.[116] One year later, he appeared in the documentary Witness to Jonestown where he responds to rare footage shot inside the Peoples Temple.[117]

Jim Jones Jr., who lost his wife and unborn child at Jonestown, returned to San Francisco. He remarried and has three sons from this marriage,[105] including Rob Jones, a high-school basketball star who went on to play for the University of San Diego before transferring to Saint Mary's College of California.[118]

Lew, Agnes, and Suzanne Jones

Lew and Agnes Jones both died at Jonestown. Agnes Jones was thirty-five years old at the time of her death.[119] Her husband[120] and four children[121][122][123][124] all died at Jonestown. Lew Jones, who was twenty-one years old at the time of his death, died alongside his wife Terry and son Chaeoke.[125][126][127] Stephanie Jones had died at age five in a car accident in May 1959.[14]

Suzanne Jones married Mike Cartmell; they both turned against the Temple and were not in Jonestown on November 18, 1978. After this decision to abandon the Temple, Jones referred to Suzanne openly as "my goddamned, no good for nothing daughter" and stated that she was not to be trusted.[128] In a signed note found at the time of her death, Marceline Jones directed that the Jones' funds were to be given to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and specified: "I especially request that none of these are allowed to get into the hands of my adopted daughter, Suzanne Jones Cartmell."[129][130] Cartmell had two children and died of colon cancer in November 2006.[131][132]

John Stoen and Kimo

Specific references to Tim Stoen, the father of John Stoen, including the logistics of possibly murdering him, are made on the Temple's final "death tape", as well as a discussion over whether the Temple should include John Stoen among those committing "revolutionary suicide".[93] At Jonestown, John Stoen was found poisoned in Jim Jones's cabin.[72]

Jim Jon (Kimo) and his mother, Carolyn Louise Moore Layton, both died during the events at Jonestown.[133]

In popular culture

Documentaries

- Jonestown: Mystery of a Massacre (1998)

- Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple (2006)

- Jonestown: Paradise Lost (2007)

- CNN Presents: Escape From Jonestown (2008)

- Seconds From Disaster, episode "Jonestown Cult Suicide" (06x01) (2012)

- Witness to Jonestown (2013)

- Jonestown: The Women Behind (2018)

American Horror Story : Cult S7 ep: 9 “Drink the Kool - Aid

Television

- Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones (1980) – fact-based miniseries; Powers Boothe won an Emmy for his portrayal of Jim Jones.

- American Horror Story: Cult (2017)

- Murder Made Me Famous -- Jim Jones Episode (03x03) (2015)

- The Simpsons episode #191 "The Joy Of Sect" features a Jones-like cult: "The Leader" claims to be building a spaceship to take adherents to the planet "Blisstonia".

Film

- Guyana: Crime of the Century aka Guyana: Cult of the Damned (1979) – Fictionalized exploitation film (depicted here as "Reverend James Johnson")

- Eaten Alive! (Italian: Mangiati vivi!) is a 1980 Italian horror film (depicted here as "Jonas," leading a cult in the jungles of Sri Lanka instead of Guyana).

- The Sacrament (2013); a found-footage horror film (depicted here simply as "Father;" in addition, Jonestown has been renamed "Eden Parish").

- Jonestown (2013) is an independent short film that dramatizes the last 24 hours in the lives of Jim Jones (played here by Leandro Cano) and The Peoples Temple Church through the eyes of a reporter.

- The Veil (2016); a supernatural horror film (depicted as "Jim Jacobs").

Fiction

- We Agreed to Meet Just Here, by Scott Blackwood. Kalamazoo, Michigan: West Michigan University Press, 2009.

- Children of Paradise, by Fred D'Aguiar. New York: HarperCollins, 2014.

- Jonestown, by Wilson Harris. London: Faber and Faber, 1996.

- Before White Night, by Joseph Hartmann. Richmond, Virginia: Belle Isle Books, 2014.

- White Nights, Black Paradise, by Sikivu Hutchinson. Infidel Books, 2015.

- Beautiful Revolutionary, by Laura Elizabeth Woollett. Scribe, London. 2018.

Poetry

- Bill of Rights, by Fred D'Aguiar. London: Chatto and Windus, 1998.

- Jonestown: A Vexation by Carmen Gillespie. Detroit, Michigan: Lotus Press, 2011.

- The Jonestown Arcane, by Jack Hirschman. Los Angeles: Parentheses Writing Series, 1991.

- Dogstar and Poems from Other Planets, by Garrett Lambrev. Berkeley, Calif.: Beatitude Press, 2007.

- A Jonestown for Worms: New Poems, by Washington S. McCuistian. Louisville, KY: Wasteland Press, 2005.

- Jonestown Lullaby, by Teri Buford O’Shea. Bloomington, Ind.: iUniverse, 2011.

- Jonestown and Other Madness, by Pat Parker. Ithaca, N.Y.: Firebrand Books, 1985.

- Jonestown, by Fraser Sutherland. Toronto, Ontario: McClelland and Stewart, 1996.

Theater

- The Peoples Temple. Written by Leigh Fondakowski, with Greg Pierotti, Stephen Wangh, and Margo Hall. Premiered in 2005. [134].

See also

- Mass suicide

- List of people who have claimed to be Jesus

- List of Buddha claimants

- The Sacrament, a fictional film compared by some critics to events that occurred at Jonestown

- David Dick, CBS News correspondent who covered Jonestown

- Marshall Applewhite

- Heaven's Gate (religious group)

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ While Jim Jones claimed to be partially of Cherokee descent through his mother Lynetta, this story was apparently not true.(Lindsay, Robert. "How Rev. Jim Jones and Black Spencer Gained His Power Over Followers". The New York Times. November 26, 1978). Lynetta's cousin Barbara Shaffer said "there wasn't an ounce of Indian in our family". (Lindsay, Robert. "How Rev. Jim Jones Gained His Power Over Followers". The New York Times. November 26, 1978). Shaffer said that Lynetta was Welsh. ("Jones—The Dark Private Side Emerges". Los Angeles Times. November 24, 1978). The birth records for Lynetta have since been lost. (Kilduff, Marshall and Ron Javers. "Jim Jones Always Led – Or Wouldn't Play". San Francisco Chronicle. December 4, 1978).

Citations

- ↑ Rolls 2014, p. 100

- ↑ Hall 1987, p. 3

- ↑ Levi 1982

- 1 2 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 9–10

- 1 2 3 Kilduff, Marshall and Javers, Ron. The Suicide Cult. Bantam Books, 1978. p. 10.

- ↑ "Jones, Jim (1931 - 1978) American Cult Leader". World of Criminal Justice, Gale. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- 1 2 Hall 1987, p. 5

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 24

- 1 2 3 Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple. American Experience, PBS.org.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 27

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 33

- 1 2 "Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple - Timeline". PBS.org. February 20, 2007.

- ↑ Knoll, James. Mass Suicide & the Jonestown Tragedy: Literature Summary. Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University. October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Wessinger 2000

- 1 2 Jones, Jim. "Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 134". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.]

- 1 2 Horrock, Nicholas M., "Communist in 1950s", The New York Times, December 17, 1978

- 1 2 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 68

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 69

- 1 2 3 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 71

- 1 2 3 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 72

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 76

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 65

- 1 2 3 Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple - People & Events PBS.org. February 20, 2007.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 63

- ↑ Jones, Jim. "Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 1023". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.

- 1 2 "The Wills of Jim Jones and Marceline Jones". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple - Race and the Peoples Temple". PBS.org. February 20, 2007.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 76–77

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 78

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 79

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 81

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 84

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 82

- 1 2 3 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 83

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 85–86

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 86

- 1 2 3 New York Times, "How Rev. Jim Jones Gained His Power Over Followers", Robert Lindsay, November 26, 1978

- ↑ Layton 1998, p. 53

- ↑ Jim Jones, Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 1053

- ↑ Jones, Jim. "The Letter Killeth". Original material reprint. Department of Religious Studies. San Diego State University.

- ↑ See, e.g., Jones, Jim in conversation with John Maher, "Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 622". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.]

- ↑ Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple. PBS.org.

- 1 2 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 302–304

- ↑ Los Angeles Times, "First Lady Among Cult's References; Mondale, Califano also listed", November 21, 1978.

- ↑ Jones, Jim. "Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 799". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.

- 1 2 Kilduff, Marshall and Phil Tracy. "Inside Peoples Temple". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University. August 1, 1977.

- ↑ Layton 1998, p. 105

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 308

- ↑ "Another Day of Death". Time. December 11, 1978.

- ↑ VanDeCarr, Paul "Death of dreams: in November 1978, Harvey Milk's murder and the mass suicides at Jonestown nearly broke San Francisco's spirit.", The Advocate, November 25, 2003

- ↑ Sawyer, Mary My Lord, What a Mourning:’ Twenty Years Since Jonestown, Jonestown Institute at SDSU

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 369

- ↑ Goodlett, Carlton B., Notes on Peoples Temple, reprinted in Moore, Rebecca and Fielding M. McGehee, III, The Need for a Second Look at Jonestown, Edwin Mellen Press, 1989, ISBN 0-88946-649-1

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 282

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 285, 306, 587

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 314

- ↑ Layton 1998, p. 113

- ↑ Hall 1987, p. 132

- ↑ Jones, Jim. "Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 50". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 451

- ↑ McCormick Maaga, Mary. Hearing the voices of Jonestown. Syracuse University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8156-0515-3.

- ↑ Moore, Rebecca. "The Demographics of Jonestown. Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University, adapted from Moore, Rebecca, Anthony Pinn and Mary Sawyer. "Demographics and the Black Religious Culture of Peoples Temple". in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. Bloomington: Indiana Press University, 2005. 57-80)

- ↑ Followership in Peoples Temple: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly by Wendy M. Edmonds

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 130–131

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 445

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 377

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 324

- ↑ "Jim Jon (Kimo) Prokes". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 408

- ↑ Hall 1987, p. 227

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 458

- 1 2 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982

- ↑ Liebert, Larry, "What Politicians Say Now About Jones", San Francisco Chronicle, November 20, 1978

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 327

- ↑ Milk, Harvey Letter Addressed to President Jimmy Carter, Dated February 19, 1978

- ↑ Moore, Rebecca. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown. Lewiston: E. Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-860-5. p. 143.

- ↑ "Accusation of Human Rights Violations by Rev. James Warren Jones". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University. April 11, 1978.

- 1 2 3 "Affidavit of Deborah Layton Blakey". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 440

- 1 2 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 481

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 476–480

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 487–488

- 1 2 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 519–520

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 524

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 516

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 527

- 1 2 3 4 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 529–531

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 533

- ↑ Who Died?, Alternative Considerations of Jonestown, San Diego State University

- ↑ 1978: Mass suicide leaves 900 dead. BBC, November 18, 2005

- ↑ Rapaport, Richard, Jonestown and City Hall slayings eerily linked in time and memory, San Francisco Chronicle, November 16, 2003

- ↑ Jim Jones, "Transcript of Recovered FBI tape Q 42". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Jonestown Audiotape Primary Project". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 559

- 1 2 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 390–391

- ↑ "Guyana Inquest – Interviews of Cecil Roberts & Cyril Mootoo" (PDF). Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ↑ Jonestown: Paradise Lost, Interview of Stephan Jones, Documentary airing on Discovery Networks, 2007

- ↑ Autopsy of Jim Jones by Kenneth H. Mueller, Jonestown Institute at SDSU

- 1 2 Wise, David. "Sex in Peoples Temple". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.

- 1 2 Paranoia And Delusions, Time, December 11, 1978

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 176–177

- ↑ "FAQ: Who was the leader of Peoples Temple?" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 505–506

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 565

- 1 2 Fish, Jon and Chris Connelly (October 5, 2007). "Outside the Lines: Grandson of Jonestown founder is making a name for himself". ESPN. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Who Survived the Jonestown Tragedy?" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Janet Marie Tupper" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Mary Elizabeth Tupper" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Ruth Ann Tupper" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Larry Howard Tupper" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Rita Jeanette Tupper Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, pp. 474–475

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Smith, Gary. "Escaping Jonestown". Sports Illustrated. CNN. December 24, 2007.

- ↑ https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/30849783

- ↑ Jones, Stephan. - "Marceline/Mom" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ Brownstein, Bill. "The son who survived Jonestown". The Gazette. Canada. March 9, 2007.

- ↑ Stephen Stept (producer, director, writer) (November 9, 2008). Witness to Jonestown. MSNBC Films.

- ↑ "22 - Rob Jones". University of San Diego Official Athletic Site. Retrieved October 3, 2009. Archived by WebCite

- ↑ Agnes Paulette Jones Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple]. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Forrest Ray Jones" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Billy Jones" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Jimbo Jones" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Michael Ray Jones" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Stephanie Jones" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ Lew Eric Jones Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Terry Carter Jones" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Chaeoke Warren Jones" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ FBI Tape Q 265 - October 17, 1978 address. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "November 18 1978 Letter from Marceline Jones". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "Letter from Marceline Jones". Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Jonestown Project: San Diego State University.

- ↑ Who Has Died Since 18 November 1978? Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ Smith, Gary. "Escape From Jonestown" Sports Illustrated CNN.com. December 24, 2007.

- ↑ "Carolyn Louise Moore Layton" Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.

- ↑ "The People's Temple, on Stage". NPR. 2005-05-01. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

Bibliography

- Chidester, David (2004). Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the People's Temple and Jonestown (Religion in North America) (2nd ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21632-8.

- Hall, John R. (1987). Gone from the Promised Land. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-88738-801-9.

- Hutchinson, Sikivu (2015). White Nights, Black Paradise. Infidel Books. ISBN 978-0-692-26713-4.

- Klineman, George; Butler, Sherman (1980). The Cult That Died. G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-399-12540-9.

- Layton, Deborah (1998). Seductive Poison. Anchor Books. ISBN 978-1-85410-600-1.

- Levi, Ken (1982). Violence and Religious Commitment: Implications of Jim Jones's People's Temple Movement. Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00296-5.

- Maaga, Mary McCormick (1998). Hearing the voices of Jonestown. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0515-7.

- Naipaul, Shiva (1980). Black & White. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-10337-1.

- Reiterman, Tom; Jacobs, John (1982). Raven: The Untold Story of Rev. Jim Jones and His People. E. P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-24136-2.

- Rolls, Geoff (2014). Classic Case Studies in Psychology (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-90961-3.

- Wessinger, Catherine (2000). How the Millennium Comes Violently: From Jonestown to Heaven's Gate. Seven Bridges Press. ISBN 978-1-889119-24-3.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jim Jones |

- The Jonestown Institute

- FBI No. Q 042 The "Jonestown Death Tape", Recorded November 18, 1978 (Internet Archive)

- Transcript of Jones's final speech, just before the mass suicide

- Jonestown Audiotape Primary Project : Transcripts

- Biography of Jim Jones Encyclopædia Britannica

- The first part of a series of articles about Jim Jones published in the San Francisco Examiner in 1972.

- History Channel Video and Stills

- Isaacson, Barry. From Silver Lake to Suicide: One Family's Secret History of the Jonestown Massacre

- Mass Suicide at Jonestown: 30 Years Later, Time magazine

- Jonestown 30 Years Later photo gallery published Friday, October 17, 2008.

- Rapaport, Richard. Jonestown and City Hall slayings eerily linked in time and memory Both events continue to haunt city a quarter century later

- Maurice Brinton. "Suicide for socialism?". Brinton's analysis of the bizarre mass suicide of a socialist cult led by American Jim Jones in Jonestown, Guyana, which discusses the dynamics of political sects in general.

- Nakao, Annie.The ghastly Peoples Temple deaths shocked the world. Berkeley Rep takes on the challenge of coming to terms with it.

- American Experience documentary, "Jonestown: The Life And Death Of Peoples Temple", shown on PBS

- Jonestown: 25 Years Later How spiritual journey ended in destruction: Jim Jones led his flock to death in jungle by Michael Taylor, San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Published Thursday, November 12, 1998.

- Utopian nightmare Jonestown: What did we learn? Larry D. Hatfield, of The Examiner staff, Gregory Lewis and Eric Brazil of The Examiner staff and Examiner Librarian Judy Canter contributed to this report. Published Sunday, November 8, 1998.

- Jones Captivated S.F.'s Liberal Elite: They were late to discover how cunningly he curried favor by Michael Taylor, San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. And [Haunted by Memories of Hell ] by Kevin Fagan, San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Published Thursday, November 12, 1998. Both stories were included in the first of a two-part series.

- The End To Innocent Acceptance Of Sects Sharper scrutiny is Jonestown legacy by Don Lattin, San Francisco Chronicle religion writer. And Most Peoples Temple Documents Still Sealed by Michael Taylor and Don Lattin, San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. And Surviving the Heart of Darkness: Twenty years later, Jackie Speier remembers how her companions and rum helped her endure the night of the Jonestown massacre by Maitland Zane, San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Published Friday, November 13, 1998. All stories were included in the second part of a two-part series.

- Inside Peoples Temple Marshall Kilduff and Phil Tracy, Used by permission of authors for the San Francisco Chronicle. Published Monday, August 1, 1977.

- Jonestown: Dismantling the Disinformation Laurie Efrein Kahalas, an 8 1⁄2-year member of the Peoples Temple who was living in the Temple building in San Francisco when tragedy struck. Published April 8, 1999.

- The Downfall of Jim Jones by Larry Lee Litke. Published on the San Diego State University Department of Religious Studies website. Originally published 1980.