Ijazah

| Part of a series on Islam |

| Usul al-fiqh |

|---|

| Fiqh |

| Ahkam |

| Theological titles |

|

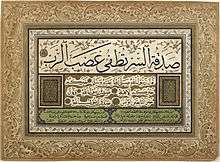

An ijazah (Arabic: الإِجازَة, "permission", "authorization", "license") is a license authorizing its holder to transmit a certain text or subject, which is issued by someone already possessing such authority. It is particularly associated with transmission of Islamic religious knowledge.[1] The license usually implies that the student has acquired this knowledge from the issuer of the ijaza through first-hand oral instruction, although this requirement came to be relaxed over time.[1] An ijaza providing a chain of authorized transmitters going back to the original author often accompanied texts of hadith, fiqh and tafsir, but also appeared in mystical, historical, and philological works, as well as literary collections.[1] While the ijaza is primarily associated with Sunni Islam, the concept also appears in the hadith traditions of Twelver Shia.[1]

George Makdisi hypothesized that the ijazah was a direct precursor to academic degrees,[2][3] a reversal of his earlier view that saw both systems as of "the most fundamental difference",[4] though this has been rejected by Toby Huff as unsubstantiated.[5]

Description

In a paper titled Traditionalism in Islam: An Essay in Interpretation,[6] Harvard professor William A. Graham explains the ijazah system as follows:

The basic system of "the journey in search of knowledge" that developed early in Hadith scholarship, involved travelling to specific authorities (shaykhs), especially the oldest and most renowned of the day, to hear from their own mouths their hadiths and to obtain their authorization or "permission" (ijazah) to transmit those in their names. This ijazah system of personal rather than institutional certification has served not only for Hadith, but also for transmission of texts of any kind, from history, law, or philology to literature, mysticism, or theology. The isnad of a long manuscript as well as that of a short hadith ideally should reflect the oral, face-to-face, teacher-to-student transmission of the text by the teacher's ijazah, which validates the written text. In a formal, written ijazah, the teacher granting the certificate typically includes an isnad containing his or her scholarly lineage of teachers back to the Prophet through Companions, a later venerable shaykh, or the author of a specific book.

Hypothesis on origins of doctorate

According to the Lexikon des Mittelalters and A History of the University in Europe, the origin of the European doctorate lies in high medieval teaching with its roots going back to late antiquity and the early days of Christian teaching of the Bible.[7][8] This view does not suggest any link between the ijazah and the doctorate.[9] Historians such as George Makdisi and his students Devin J. Stewart, Josef W. Meri, and Shawkat Toorawa have instead stated that the ijazah was an early type of academic degree or doctorate issued in early medieval madrasahs, similar to that which later appeared in European medieval universities.[3][2] Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia draws parallels between the Islamic ijazah and European doctorate,[3] though the entry on the "Madrasa" in the Encyclopedia of Islam draws no such parallels.[10]

Makdisi, in a 1970 investigation into the differences between the Christian university and the Islamic madrasah, was initially of the opinion that the Christian doctorate of the medieval university was the one element in the university that was the most different from the Islamic ijazah certification.[4] In 1989, though, he said that the origins of the Christian medieval doctorate ("licentia docendi") date to the ijāzah al-tadrīs wa al-iftā' ("license to teach and issue legal opinions") in the medieval Islamic legal education system.[2] Makdisi proposed that the ijazat attadris was the origin of the European doctorate, and went further in suggesting an influence upon the magisterium of the Christian Church.[11] According to the 1989 paper, the ijazat was equivalent to the Doctor of Laws qualification and was developed during the 9th century after the formation of the Madh'hab legal schools. To obtain a doctorate, a student "had to study in a guild school of law, usually four years for the basic undergraduate course" and at least ten years for a post-graduate course. The "doctorate was obtained after an oral examination to determine the originality of the candidate's theses," and to test the student's "ability to defend them against all objections, in disputations set up for the purpose" which were scholarly exercises practiced throughout the student's "career as a graduate student of law." After students completed their post-graduate education, they were awarded doctorates giving them the status of faqih (meaning "master of law"), mufti (meaning "professor of legal opinions") and mudarris (meaning "teacher"), which were later translated into Latin as magister, professor and doctor respectively.[2]

Madrasas issued the ijazat attadris in a single field, the Islamic religious law of Sharia.[12] Other academic subjects, including the natural sciences, philosophy and literary studies, were treated "ancillary" to the study of the Sharia.[13] The Islamic law degree in Al-Azhar University, the most prestigious madrasa, was traditionally granted without final examinations, but on the basis of the students' attentive attendance to courses.[14] However, the postgraduate doctorate in law was only obtained after "an oral examination."[15] In a 1999 paper, Makdisi points out that, in much the same way granting the ijazah degree was in the hands of professors, the same was true for the early period of the University of Bologna, where degrees were originally granted by professors.[16] He also points out that, much like the ijazat attadris was confined to law, the first degrees at Bologna were also originally confined to law, before later extending to other subjects.[17]

Makdisi's thesis has led to further research on the topic by historians such as Stewart, Meri, Lowery and Toorawa.[3] However, several other scholars have criticized Makdisi's work. Norman Daniel, in a 1984 paper, criticized an earlier work of Makdisi for relying on similarities between the two education systems rather than citing historical evidence for a transmission. He stated that Makdisi "does not seriously consider the spontaneous recurrence of phenomena", and notes that similarities between two systems do not automatically imply that one has created the other. He further states that there is a lack of evidence for schools in the short-lived Arab settlements of France and mainland Italy, which Makdisi argues may have been links between the Islamic and European educational systems, as well as a lack of evidence of the alleged transmission of scholastic ideas between the two systems altogether.[18] In a discussion of Makdisi's 1989 thesis, Toby Huff argued that there was never any equivalent to the bachelor's degree or doctorate in the Islamic madrasahs, owing to the lack of a faculty teaching a unified curriculum.[19]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Vajda, G., Goldziher, I. and Bonebakker, S.A. (2012). "Id̲j̲āza". In P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3485. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 Makdisi, George (April–June 1989), "Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 109 (2): 175–182 [175–77], doi:10.2307/604423, JSTOR 604423

- 1 2 3 4 Devin J. Stewart, Josef W. Meri (2005). Degrees, or Ijazah. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 201–203. ISBN 9781135455965.

- 1 2 Makdisi, George (1970). "Madrasa and University in the Middle Ages". Studia Islamica (32): 255–264 (260). doi:10.2307/1595223.

Perhaps the most fundamental difference between the two systems is embodied in their systems of certification; namely, in medieval Europe, the licentia docendi, or license to teach; in medieval Islam, the ijaza, or authorization. In Europe, the license to teach was a license to teach a certain field of knowledge. It was conferred by the licensed masters acting as a corporation, with the consent of a Church authority ... Certification in the Muslim East remained a personal matter between the master and the student. The master conferred it on an individual for a particular work, or works. Qualification, in the strict sense of the word, was supposed to be a criterion, but it was at the full discretion of the master

- ↑ Huff, Toby E. (2007). The rise of early modern science : Islam, China, and the West (2. ed., repr. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0521529948.

It remains the case that no equivalent of the bachelor's degree, the licentia docendi, or higher degrees ever emerged in the medieval or early modern Islamic madrasas.

- ↑ Graham, William A. (Winter 1993), "Traditionalism in Islam: An Essay in Interpretation", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, MIT Press, 23 (3): 495–522, doi:10.2307/206100, JSTOR 206100

- ↑ Verger, J. (1999), "Doctor, doctoratus", Lexikon des Mittelalters, 3, Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, cols 1155–1156

- ↑ Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX: "No other European institution has spread over the entire world in the way in which the traditional form of the European university has done. The degrees awarded by European universities – the bachelor's degree, the licentiate, the master's degree, and the doctorate – have been adopted in the most diverse societies throughout the world."

- ↑ Cf. Lexikon des Mittelalters, J.B. Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, entries on: Baccalarius, Doctor, Grade, universitäre, Licentia, Magister universitatis, Professor, Rector

- ↑ Pedersen, J.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R. "Madrasa." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C. E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010, retrieved 21 March 2010)

- ↑ Makdisi, George (April–June 1989), "Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 109 (2): 175–182 [175–77], doi:10.2307/604423, JSTOR 604423,

I hope to show how the Islamic doctorate had its influence on Western scholarship, as well as on the Christian religion, creating there a problem still with us today. [...] As you know, the term doctorate comes from the Latin docere, meaning to teach; and the term for this academic degree in medieval Latin was licentia docendi, "the license to teach." This term is the word for word translation of the original Arabic term, ijazat attadris. In the classical period of Islam's system of education, these two words were only part of the term; the full term included wa I-ifttd, meaning, in addition to the license to teach, a "license to issue legal opinions." [...] The doctorate came into existence after the ninth century Inquisition in Islam. It had not existed before, in Islam or anywhere else. [...] But the influence of the Islamic doctorate extended well beyond the scholarly culture of the university system. Through that very system it modified the millennial magisterium of the Christian Church. [...] Just as Greek non-theistic thought was an intrusive element in Islam, the individualistic Islamic doctorate, originally created to provide machinery for the Traditionalist determination of Islamic orthodoxy, proved to be an intrusive element in hierarchical Christianity. In classical Islam the doctorate consisted of two main constituent elements: (I) competence, i.e., knowledge and skill as a scholar of the law; and (2) authority, i.e., the exclusive and autonomous right, the jurisdictional authority, to issue opinions having the value of orthodoxy, an authority known in the Christian Church as the magisterium. [...] For both systems of education, in classical Islam and the Christian West, the doctorate was the end-product of the school exercise, with this difference, however, that whereas in the Western system the doctorate at first merely meant competence, in Islam it meant also the jurisdictional magisterium.

- ↑ Makdisi, George (April–June 1989), "Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 109 (2): 175–182 [176], doi:10.2307/604423, JSTOR 604423,

There was no other doctorate in any other field, no license to teach a field, except that of the religious law. To obtain a doctorate, one had to study in a guild school of law.

- ↑ Pedersen, J.; Rahman, Munibur; Hillenbrand, R. "Madrasa." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010, retrieved 20 March 2010: "Madrasa,...in mediaeval usage, essentially a college of law in which the other Islamic sciences, including literary and philosophical ones, were ancillary subjects only."

- ↑ Jomier, J. "al- Azhar (al-Ḏj̲āmiʿ al-Azhar)." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2010: "There was no examination at the end of the course of study. Many of the students were well advanced in years. Those who left al-Azhar obtained an idjāza or licence to teach; this was a certificate given by the teacher under whom the student had followed courses, testifying to the student's diligence and proficiency."

- ↑ Makdisi, George (April–June 1989), "Scholasticism and Humanism in Classical Islam and the Christian West", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 109, No. 2, 109 (2): 175–182 (176), doi:10.2307/604423, JSTOR 604423

- ↑ George Makdisi (1999), "Religion and Culture in Classical Islam and the Christian West", in Richard G. Hovannisian & Georges Sabagh, Religion and culture in medieval Islam, Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–23 [10], ISBN 0-521-62350-2

- ↑ George Makdisi (1999), "Religion and Culture in Classical Islam and the Christian West", in Richard G. Hovannisian & Georges Sabagh, Religion and culture in medieval Islam, Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–23 [10–1], ISBN 0-521-62350-2

- ↑ Norman Daniel: Review of "The Rise of Colleges. Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West by George Makdisi", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 104, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 1984), pp. 586–588 (587)

- ↑ Toby Huff, Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China and the West, 2nd ed., Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-52994-8, p. 155: "It remains the case that no equivalent of the bachelor's degree, the licentia docendi, or higher degrees ever emerged in the medieval or early modern Islamic madrasas."