Hejira (album)

| Hejira | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Joni Mitchell | ||||

| Released | November 1976 | |||

| Recorded | 1976 | |||

| Studio | A&M Studios, Hollywood | |||

| Genre | Folk jazz, pop jazz, jazz fusion | |||

| Length | 52:18 | |||

| Label | Asylum | |||

| Producer | Joni Mitchell | |||

| Joni Mitchell chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Robert Christgau | B+[2] |

| Le Guide du CD | GOLD[3] |

| MusicHound | |

| Pitchfork Media | 8.0/10[5] |

| Rolling Stone | (favorable)[6] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Martin C. Strong | 9/10[3] |

| Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Polari Magazine | |

Hejira is the eighth studio album by Canadian singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell, released in 1976.

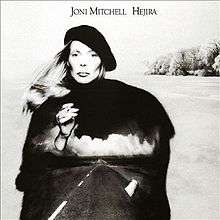

The songs on the album were largely written by Mitchell on a trip by car from Maine back to Los Angeles, California, with prominent imagery including highways, small towns and snow. The photographs of Mitchell on the front and back cover were taken by Norman Seeff and appear against a backdrop of Lake Mendota, in Madison, Wisconsin, after an ice storm.[9]

Characterized by lyrically dense, sprawling songs, and the distinctive fretless bass playing of Jaco Pastorius, Hejira marked Mitchell's turn towards the jazz-based music she would implement on later recordings. The album did not sell as well as its predecessors, peaking at #22 in Mitchell's native Canada. It also reached #13 on the Billboard 200 pop album chart in the United States (where it was certified gold by RIAA), and #11 in the UK, where it attained a silver certification. Critically, the album was generally well received, and in the years since its release, Hejira has been recognized as one of the high-water marks in Mitchell's career.

Recording sessions

Background

According to Mitchell, the album was written during or after three journeys she took in late 1975 and the first half of 1976. The first was a stint as a member of Bob Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue in late 1975. During this time period, she became a frequent cocaine user, and it would take several years for her to kick the addiction.

In February 1976, Mitchell was scheduled to play about six weeks of concert dates across the US promoting The Hissing of Summer Lawns. However, the relationship between Mitchell and her boyfriend John Guerin (who was acting as her drummer on the string of dates) soured, possibly due to Mitchell's fling with director Sam Shepard during the Rolling Thunder Revue. Tensions became so fraught that the tour was abandoned about halfway through.

The third trip came soon after when Mitchell traveled across America with two men, one of them being a former lover from Australia. This trip inspired six of the songs on the album. She drove with her two friends from Los Angeles to Maine, and then went back to California alone via Florida and the Gulf of Mexico. She traveled without a driver's licence and stayed behind truckers, relying on their habit of signaling when the police were ahead of them; consequently, she only drove in daylight hours.[10][11]

During some of her solo journeys, Mitchell donned a red wig, sunglasses, and told the varying strangers she met that her name was either "Charlene Latimer" or "Joan Black."[12] Despite the disguise, Mitchell was still sometimes recognized.

Collaboration with Jaco Pastorius

During the recording of her albums Court and Spark and The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Mitchell grew increasingly frustrated by the rock session musicians who had been hired to perform her music. "...There were grace notes and subtleties and things that I thought were getting kind of buried."[13] The session musicians in turn recommended that Mitchell start looking for jazz instrumentalists to perform on her records. In addition, her relationship with drummer and musician John Guerin (which lasted through a significant portion of the mid-1970s) influenced her decision to move more towards experimental jazz music and further away from her folk and pop roots.

After recording the basic tracks that would become Hejira, Mitchell met bassist Jaco Pastorius and they formed an immediate musical connection;[14] Mitchell was dissatisfied with what she called the "dead, distant bass sound" of the 1960s and early 1970s, and was beginning to wonder why the bass part always had to play the root of a chord.[15] She overdubbed his bass parts on four of the tracks on Hejira and released the album in November 1976.[14]

Dominated by Mitchell's guitar and Pastorius's distinctive fretless bass, the album drew on a range of influences but was more cohesive and accessible than some of her later more jazz-oriented work. "Coyote", "Amelia" and "Hejira" became concert staples shortly after Hejira's release, especially after being featured on the live album Shadows and Light, alongside "Furry Sings the Blues" and "Black Crow".

Album title

The album title is a transliteration of the Arabic word "hijra", which means "journey", usually referring to the migration of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (and his companions) from Mecca to Medina in 622. She later stated that when she chose the title, she was looking for a word that meant "running away with honor."[16] She found the word "hejira" while reading the dictionary, and was drawn to the "dangling j, like in Aja... it's leaving the dream, no blame".[16]

Songs

Mitchell has described the album as "really inspired... there is this restless feeling throughout it... The sweet loneliness of solitary travel",[17] and has said that "I suppose a lot of people could have written a lot of my other songs, but I feel the songs on Hejira could only have come from me."[10]

Coyote

Hejira opens with "Coyote", about a one-night stand with a ladies' man,[10] speculated by several biographers to be playwright and actor Sam Shepard.[18] Mitchell would later perform the song with The Band at their farewell concert, which was eventually released under the title The Last Waltz (1978).

Amelia

The second track on Hejira, "Amelia", was inspired by Mitchell's breakup with Guerin, and described by her as almost an exact account of her experience in the desert.[10] The song interweaves a story of a desert journey (the "hejira within the hejira"[19]) with the famous aviator Amelia Earhart who mysteriously vanished during a flight over the Pacific Ocean. Mitchell has commented on the origins of the song: "I was thinking of Amelia Earhart and addressing it from one solo pilot to another... sort of reflecting on the cost of being a woman and having something you must do." [17] The song, each verse of which ends with the refrain "Amelia, it was just a false alarm", repeatedly shifts between two keys, giving it a constant unsettled feeling.[20]

Furry Sings the Blues

"Furry Sings the Blues", which features Neil Young on harmonica, was inspired by a meeting in 1975 that came about between Mitchell and the blues guitarist and singer Furry Lewis in Memphis after she had "hit on" a local policeman. In exchange for Mitchell taking him to a record store in her limousine, he showed her Beale Street, where she met a pawn shop owner who introduced her to Lewis.[17][21] She brought Lewis a carton of cigarettes and a bottle of alcohol in hopes of gaining his good graces.

Lewis was displeased with Mitchell's unauthorized use of his name and "hated" the song.[22][23] He told Rolling Stone in February 1977: "She shouldn't have used my name in no way, shape, form or faction without consultin' me 'bout it first. The woman came over here and I treated her right, just like I does everybody that comes over. She wanted to hear 'bout the old days, said it was for her own personal self, and I told it to her like it was, gave her straight oil from the can."[23]

Mitchell would return to the song live in concert throughout the years. After not performing live since 2002, Mitchell played "Furry Sings the Blues" (as well as "Don't Interrupt the Sorrow" from The Hissing of Summer Lawns and "Woodstock" from Ladies of the Canyon) during her birthday tribute at Massey Hall on June 18 and 19, 2013. This was Mitchell's final public performance to date.

A Strange Boy

"A Strange Boy" recounts the affair Mitchell had with one of the men she was traveling with from Los Angeles to Maine; he was a flight attendant in his thirties who lived with his parents.[10]

Hejira

"Hejira" is about Mitchell's reasons for leaving John Guerin, and Mitchell described it as probably the toughest tune on the album to write.[10] It features the bass work of Pastorius, who was inspired by Mitchell's use of multi-tracking with her guitar to mix four separate tracks of his carefully arranged bass parts, having them all play together at certain points of the tune.[24]

Song for Sharon

Side two of Hejira begins with the epic "Song for Sharon", which at eight minutes and 40 seconds stands as the longest track on the album. The lyrics deal with the conflict faced by a woman who is deciding between freedom and marriage. The song references the places Mitchell went during her trip to New York City, including scenes at Mandolin Brothers in Staten Island and a visit to a fortune teller on Bleecker Street.[10][25] The song was allegedly written while Mitchell was high on cocaine at the end of her visit to the city.[10]

The namesake of the song was her childhood friend Sharon Bell, who studied voice and wanted to be a singer when she was young but married a farmer; Mitchell wanted to be a farmer's wife, but ended up becoming a singer.[26] The song also mentions the blowout fight and abandoned midwestern tour that served as the death knell for Mitchell's relationship with Guerin: "I left my man at a North Dakota junction, and I came out to the Big Apple here to face the dream's malfunction."

According to biographer Sheila Weller, "Song For Sharon" also makes a coded reference to the March 1976 suicide of Jackson Browne's wife, fashion model Phyllis Major.[27][28] Browne and Mitchell had a brief, "high-strung" affair in 1972; on at least one occasion, Browne allegedly physically abused Mitchell.[29] After their relationship dissolved, Browne quickly married Major.[27] Although Major had died from a barbiturate overdose, Mitchell sang "A woman I knew just drowned herself", and questioned if her suicide was a means of "punishing somebody".[28]

Black Crow

"Black Crow"'s lyrics deal with the practical difficulty for Mitchell of traveling from her second home on British Columbia's Sunshine Coast.[10]

Blue Motel Room

"Blue Motel Room" was written at the DeSoto Beach Motel in Savannah, Georgia. The song was inspired by the first breakup of the on-again-off-again relationship between Mitchell and Guerin.[30] The lyrics express Mitchell's hopes of rekindling their relationship, and she tells her love interest to rebuff any other suitors: "Tell those girls that you've got German Measles, honey tell 'em you've got germs."[10]

Refuge of the Roads

"Refuge of the Roads" was written about a three-day visit that Mitchell had made to the Buddhist meditation master Chögyam Trungpa in Colorado on her way back to Los Angeles.[10][31] Mitchell would later say that "Refuge of the Roads" was one of her own favorite songs,[30] and would re-record the tune, along with "Amelia" and "Hejira", with a full orchestra for her 2002 album Travelogue.

Release

Commercially the album did not do as well as its two predecessors. Despite reaching #13 on the Billboard 200 pop album chart and being certified Gold, it failed to get significant airplay on commercial radio. Critically, the album was, however, generally well received, and it has since been recognized as one of the high-water marks in Mitchell's career.

In 1991 Rolling Stone cited the album's cover as the 11th greatest album cover of all time.[32]

In 2000 German Spex magazine critics voted it the 55th greatest album of the 20th century, calling it "a self-confident, coolly elegant design".

The album was included in Robert Dimery's 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.

Track listing

All tracks written by Joni Mitchell.

| Side one | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "Coyote" | 5:01 |

| 2. | "Amelia" | 6:01 |

| 3. | "Furry Sings the Blues" | 5:07 |

| 4. | "A Strange Boy" | 4:15 |

| 5. | "Hejira" | 6:42 |

| Side two | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 6. | "Song for Sharon" | 8:40 |

| 7. | "Black Crow" | 4:22 |

| 8. | "Blue Motel Room" | 5:04 |

| 9. | "Refuge of the Roads" | 6:42 |

Personnel

- Joni Mitchell – vocals, acoustic guitar and electric guitars

- Larry Carlton – electric guitar on "Amelia", "A Strange Boy" and "Black Crow"; acoustic guitar on "Blue Motel Room"

- Jaco Pastorius – bass guitar on "Coyote", "Hejira", "Black Crow" and "Refuge of the Roads"

- Max Bennett – bass guitar on "Furry Sings the Blues" and "Song for Sharon"

- Chuck Domanico – double bass on "Blue Motel Room"

- John Guerin – drums on "Furry Sings the Blues", "Song for Sharon", "Blue Motel Room" and "Refuge of the Roads"

- Bobbye Hall – percussion on "Coyote", "A Strange Boy" and "Hejira"

- Victor Feldman – vibraphone on "Amelia"

- Neil Young – harmonica on "Furry Sings the Blues"

- Abe Most – clarinet on "Hejira"

- Chuck Findley, Tom Scott – horns on "Refuge of the Roads"

Production

- Henry Lewy – production, recording, mixing

- Steve Katz – assistant production, mixing

- Keith Williamson – art direction

- Joel Bernstein, Norman Seeff – photography

References

- ↑ Cleary, David (2011). "Hejira – Joni Mitchell | AllMusic". allmusic.com. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ Christgau, R. (2011). "Robert Christgau: CG: joni mitchell". robertchristgau.com. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Joni Mitchell Hejira". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (eds) (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 769. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ↑ Hopper, Jessica (November 9, 2012). "Joni Mitchell studio albums review". pitchfork.com. Retrieved March 18, 2014.

- ↑ Swartley, Ariel (2011). "Hejira by Joni Mitchell | Rolling Stone Music | Music Reviews". rollingstone.com. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian, eds. (2004). "Joni Mitchell". The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. London: Fireside. pp. 547–548. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8. Retrieved 8 September 2009. Portions posted at "Joni Mitchell > Album Guide". rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ↑ Bryant, Christopher (26 March 2009). "Hejira • Joni Mitchell". polarimagazine.com. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Doug Moe, "Joni Mitchell and Lake Mendota", The Capital Times, March 31, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Fisher, Doug (October 8, 2006). "The trouble she's seen". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Ruhlman, William (February 17, 1995). "From Blue to Indigo". Goldmine. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Mercer, Michelle (2009). Will You Take Me As I Am: Joni Mitchell's Blue Period. Simon and Schuster. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-1-4165-6655-7. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ Weller, Sheila (2008). Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon -- and The Journey of a Generation. New York, NY: Atria Books. p. 412. ISBN 0743491483.

- 1 2 Breese, Wally (January 1998). "Biography: 1976–1977 Refuge of the Roads". Jonimitchell.com. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Mitchell, Joni (December 1987). "The Life and Death of Jaco Pastorius". Musician. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- 1 2 Daily Motion video: "Joni Mitchell: Painting With Words and Music."

- 1 2 3 Hilburn, Robert (December 8, 1996). "Both Sides, Later". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Friedman, Roger (April 1, 2008). "Joni Mitchell's '70s Suicide Attempt". Fox News. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Ron (December 4, 2007), "The Best Joni Mitchell Song Ever", Slate

- ↑ Manoff, Tom, Joni Mitchell's Stylistic Journey, PBS

- ↑ Levitin, Daniel (1996). "A conversation with Joni Mitchell" (PDF). Grammy Magazine. Vol. 14 no. 2. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ "newsobserver.com |On the Beat: David Menconi on music – Elvis forever and ever, amen". Blogsarchive.newsobserver.com. Archived from the original on 2009-04-02. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- 1 2 Rolling Stone article: "Furry Lewis is Furious at Joni." February 24, 1977.

- ↑ Suchow, Rick (December 2011). "Jaco at 60: his legacy lives on". Bass Musician. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Ohrstrom, Lysandra (July 15, 2008). "Mandolin 'Mecca' on Staten Island". The New York Observer. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Aikins, Mary (July 2005). "Heart of a Prairie Girl". Reader's Digest. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- 1 2 http://www.lamag.com/culturefiles/a-requiem-for-jackson-brownes-dream/

- 1 2 Weller, Sheila (2008). Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon -- and The Journey of a Generation. New York, NY: Atria Books. pp. 410–411. ISBN 0743491483.

- ↑ Weller, Sheila (2008). Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon -- and The Journey of a Generation. New York, NY: Atria Books. p. 407. ISBN 0743491483.

- 1 2 Weller, Sheila (2008). Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon -- and The Journey of a Generation. New York, NY: Atria Books. p. 415. ISBN 0743491483.

- ↑ Ehrlich, Dimitri (April 1991). "Joni Mitchell". Interview. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Rolling Stone's 100 Greatest Album Covers". Rate Your Music. 1991-11-14. Retrieved 2012-02-21.