Sam Shepard

| Sam Shepard | |

|---|---|

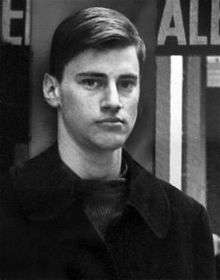

Shepard in 2004 | |

| Born |

Samuel Shepard Rogers III November 5, 1943 Fort Sheridan, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died |

July 27, 2017 (aged 73) Midway, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1962–2017 |

| Works | Filmography |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Partner(s) | Jessica Lange (c. 1982; sep. 2009) |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Full list |

| Website |

www |

| Signature | |

| |

Samuel Shepard Rogers III (November 5, 1943 – July 27, 2017), known professionally as Sam Shepard, was an American actor, playwright, author, screenwriter, and director whose career spanned half a century.[1] He won ten Obie Awards for writing and directing, the most won by any writer or director. He wrote 44 plays as well as several books of short stories, essays, and memoirs. Shepard received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1979 for his play Buried Child and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of pilot Chuck Yeager in the 1983 film The Right Stuff. He received the PEN/Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater Award as a master American dramatist in 2009. New York magazine described Shepard as "the greatest American playwright of his generation."[2]

Shepard's plays are known for their bleak, poetic, surrealist elements, black comedy, and rootless characters living on the outskirts of American society.[3] His style evolved from the absurdism of his early off-off-Broadway work to the realism of later plays like Buried Child and Curse of the Starving Class.[4]

Early life

Shepard was born on November 5, 1943, in Fort Sheridan, Illinois.[5] He was named Samuel Shepard Rogers III after his father, Samuel Shepard Rogers, Jr., but was called Steve Rogers.[6] Samuel Shepard Rogers, Jr. was a teacher and farmer who served in the United States Army Air Forces as a bomber pilot during World War II. Shepard characterized his father as "a drinking man, a dedicated alcoholic".[7] His mother, Jane Elaine (née Schook), was a teacher and a native of Chicago.[8]

Shepard worked on a ranch as a teenager. After graduating from Duarte High School in Duarte, California in 1961, he briefly studied animal husbandry at nearby Mt. San Antonio College.[7][9] While at college, Shepard became enamored of Samuel Beckett, jazz, and abstract expressionism. He dropped out to join a touring repertory group, the Bishop's Company.

Career

Writing

Shepard found work as a busboy at the Village Gate nightclub when he arrived in New York City, and in 1962 became involved in the off-off-Broadway theater scene through Ralph Cook, the Village Gate's head waiter. Steve Rogers then adopted the professional name Sam Shepard.[6] Although his plays would eventually be staged at several off-off-Broadway venues, Shepard was most closely connected with Cook's Theatre Genesis, housed at St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery in the East Village.[10]

In 1965, Shepard's one-act plays Dog and The Rocking Chair were produced at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club.[11] This was the first in many productions of Shepard's work at La MaMa during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. In 1967, Tom O'Horgan directed Shepard's Melodrama Play alongside Leonard Melfi's Times Square and Rochelle Owens' Futz at La MaMa.[12] In 1969, Jeff Bleckner directed Shepard's science fiction play The Unseen Hand at La MaMa.[13] The Unseen Hand would later influence Richard O'Brien's musical The Rocky Horror Show. Bleckner then directed The Unseen Hand alongside Forensic and the Navigators at the nearby Astor Place Theater in 1970.[14]

Shepard's play Shaved Splits was directed at La MaMa in 1970 by Bill Hart.[15] Seth Allen directed Melodrama Play at La MaMa the following year.[16] In 1981, Tony Barsha directed The Unseen Hand at La MaMa. The production then transferred to the Provincetown Playhouse and ran for over 100 performances.[17] Syracuse Stage co-produced The Tooth of Crime at La MaMa in 1983.[18] Also in 1983, the Overtone Theatre and New Writers at the Westside co-produced Shepard's plays Superstitions and The Sad Lament of Pecos Bill on the Eve of Killing His Wife at La MaMa.[19] John Densmore performed in his own play Skins and Shepard and Joseph Chaikin's play Tongues, directed as a double bill by Tony Abatemarco, at La MaMa in 1984.[20] Nicholas Swyrydenko directed a production of Geography of a Horse Dreamer at La MaMa in 1985.[21]

Several of Shepard's early plays, including Red Cross (1966) and La Turista (1967), were directed by Jacques Levy. A patron of the Chelsea Hotel scene, he also contributed to Kenneth Tynan's Oh! Calcutta! (1969) and drummed sporadically from 1967 through 1971 with the psychedelic folk band The Holy Modal Rounders, appearing on their albums Indian War Whoop (1967) and The Moray Eels Eat The Holy Modal Rounders (1968). After winning six Obie Awards between 1966 and 1968, Shepard emerged as a screenwriter with Robert Frank's Me and My Brother (1968) and Michelangelo Antonioni's Zabriskie Point (1970).

Cowboy Mouth, a collaboration with his then-lover Patti Smith, was staged at The American Place Theatre in April 1971, providing early exposure for Smith, who became a well-known musician. The story and characters in Cowboy Mouth were loosely inspired by Shepard and Smith's relationship. After opening night, he abandoned the production and fled to New England without a word to anyone involved.[22]

Shortly thereafter, Shepard relocated with his wife and son to London. While in London, he immersed himself in the study of G. I. Gurdjieff's Fourth Way, a recurring preoccupation for much of his life. Returning to the United States in 1975, he moved to the 20-acre Flying Y Ranch in Mill Valley, California, where he raised a young colt named Drum and rode double with his young son on an appaloosa named Cody.[23][24][25][26][27] Shepard continued to write plays and served for a semester as Regents' Professor of Drama at the University of California, Davis.

Shepard accompanied Bob Dylan on the Rolling Thunder Revue of 1975 as the screenwriter for Renaldo and Clara that emerged from the tour. However, because much of the film was improvised, Shepard's work was seldom used. His diary of the tour, Rolling Thunder Logbook, was published in 1978. A decade later, Dylan and Shepard co-wrote the 11-minute song "Brownsville Girl", included on Dylan's 1986 Knocked Out Loaded album and on later compilations.

In 1975, Shepard was named playwright-in-residence at the Magic Theatre in Omaha, Nebraska, where he created many of his notable works, including his Family Trilogy. One of the plays in the trilogy, Buried Child (1978), won the Pulitzer Prize, and was nominated for five Tony Awards.[28] This marked a major turning point in his career, heralding some of his best-known work, including True West (1980), Fool for Love (1983), and A Lie of the Mind (1985). A comic tale of reunion, in which a young man drops in on his grandfather's Illinois farmstead only to be greeted with indifference by his relations, Buried Child saw Shepard stake a claim to the psychological terrain of classic American theater. True West and Fool for Love were subsequently nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.[29][30] Some critics have expanded the trilogy to a quintet, including Fool for Love and A Lie of the Mind. Shepard won a record-setting 10 Obie Awards for writing and directing between 1966 and 1984.

In 2010, A Lie of the Mind was revived in New York at the same time as Shepard's new play Ages of the Moon opened there.[31] Reflecting on the two plays, Shepard said that the older play felt "awkward", adding, "All of the characters are in a fractured place, broken into pieces, and the pieces don't really fit together," while the newer play "is like a Porsche. It's sleek, it does exactly what you want it to do, and it can speed up but also shows off great brakes."[32] The revival and the new play also coincided with the publication of Shepard's collection Day out of Days: Stories.[33] The book includes "short stories, poems and narrative sketches... that developed from dozens of leather-bound notebooks [Shepard] carried with him over the years."[32]

Acting

Shepard began his acting career when cast in a major role as the doomed land baron in Terrence Malick's Days of Heaven (1978), opposite Richard Gere and Brooke Adams.[29] This led to other important film roles, including that of Cal, Ellen Burstyn's character's love interest in Resurrection (1980), and, most notably, Shepard's portrayal of Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff (1983). The latter performance earned Shepard an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor. By 1986, Fool for Love was getting a film adaptation directed by Robert Altman, with Shepard in the lead role; A Lie of the Mind was being performed Off-Broadway with an all-star cast (including Harvey Keitel and Geraldine Page); and Shepard was working steadily as a film actor. Together, these achievements put him on the cover of Newsweek.

Over the years, Shepard taught extensively on playwriting and other aspects of theater. He gave classes and seminars at various theater workshops, festivals, and universities. Shepard was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1986, and was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1986.[34] In 2000, Shepard demonstrated his gratitude to the Magic Theatre by staging The Late Henry Moss as a benefit for the theatre, in San Francisco. The cast included Nick Nolte, Sean Penn, Woody Harrelson, and Cheech Marin. The limited, three-month run was sold out. In 2001, Shepard played General William F. Garrison in the film Black Hawk Down. Although he was cast in a supporting role, Shepard enjoyed renewed interest in his talent for screen acting.

Shepard performed Spalding Gray's final monologue, Life Interrupted, for the audiobook version, released in 2006. In 2007, Shepard contributed banjo to Patti Smith's cover of Nirvana's song "Smells Like Teen Spirit" on her album Twelve. Although many artists had an influence on Shepard's work, one of the most significant was Joseph Chaikin, a veteran of The Living Theatre and founder of The Open Theater.[10] The two worked together on various projects, and Shepard has stated that Chaikin was a valuable mentor.

In 2011, Shepard starred in the film Blackthorn. His final film appearance is Never Here, which premiered in June 2017 but had been filmed in the fall of 2014.[35] Shepard also appeared in the television series Bloodline between 2014-2017.[36]

Directing

At the beginning of his career, Shepard did not direct his own plays. His early plays had a number of different directors, but were most frequently directed by Ralph Cook, the founder of Theatre Genesis. Later, while living at the Flying Y Ranch, Shepard formed a successful playwright-director relationship with Robert Woodruff, who directed the premiere of Buried Child (1982), among other plays. During the 1970s, Shepard decided that his vision for his plays required him to direct them himself. He directed many of his own plays from that point on. With only a few exceptions, he did not direct plays by other playwrights. He also directed two films, but reportedly did not see film directing as a major interest.

Personal life

When Shepard first arrived in New York City, he roomed with Charlie Mingus, Jr., a friend from high school and the son of jazz musician Charles Mingus. He then lived with actress Joyce Aaron. From 1969 to 1984, he was married to actress O-Lan Jones, with whom he had one son, Jesse Mojo Shepard (born 1970). From 1970 to 1971, Shepard was involved in an extramarital affair with musician Patti Smith, who remained unaware of Shepard's identity as a multiple Obie Award-winning playwright until it was divulged to her by Jackie Curtis. According to Smith, "Me and his wife still even liked each other. I mean, it wasn't like committing adultery in the suburbs or something."[37]

Shepard met Academy Award-winning actress Jessica Lange on the set of the film Frances, in which they were both acting. He moved in with her in 1983, and they were together for nearly 30 years; they separated in 2009.[38] They had two children, Hannah Jane Shepard (born 1986) and Samuel Walker Shepard (born 1987). In 2003, Shepard's elder son, Jesse, wrote a book of short stories, and Shepard appeared with him at a reading at City Lights Bookstore.[39]

Despite having a longstanding aversion to flying, Shepard allowed Chuck Yeager to take him up in a jet plane in 1982, in preparation to play the pilot in the film The Right Stuff.[40][41] Shepard cited his fear of flying as a source for a character in his 1966 play Icarus's Mother.[42] He went through an airliner crash in the film Voyager, and apparently vowed never to fly again after a turbulent trip on an airliner returning from Mexico in the 1960s.[43]

In the early morning hours of January 3, 2009, Shepard was arrested and charged with speeding and drunk driving in Normal, Illinois.[44] He pled guilty to both charges on February 11, 2009, and was sentenced to 24 months probation, alcohol education classes, and 100 hours of community service.[45] On May 25, 2015, Shepard was arrested again, this time in Santa Fe, New Mexico, for aggravated drunk driving.[46]

His 50-year friendship with Johnny Dark, stepfather to O-Lan Jones, was the subject of the 2013 documentary Shepard & Dark by Treva Wurmfeld.[47] A collection of Shepard and Dark's correspondence, Two Prospectors, was also published that year.[48]

Shepard died on July 27, 2017, at his home in Kentucky, aged 73, from complications of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[5][49][50] Patti Smith paid homage to their long collaboration in The New Yorker.[51]

Archives

Sam Shepard's papers are split between the Wittliff Collections of Southwestern Writers at Texas State University, comprising 27 boxes (13 linear feet)[52] and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, comprising 30 document boxes (12.6 linear feet).[53]

Bibliography

- Plays

- 1964: Cowboys

- 1964: The Rock Garden

- 1965: Chicago

- 1965: Icarus's Mother

- 1965: 4-H Club

- 1966: Red Cross

- 1967: La Turista

- 1967: Cowboys #2

- 1967: Forensic & the Navigators

- 1969: The Unseen Hand

- 1969: Oh! Calcutta! (contributed sketches)

- 1970: The Holy Ghostly

- 1970: Operation Sidewinder

- 1971: Mad Dog Blues

- 1971: Back Bog Beast Bait

- 1971: Cowboy Mouth (with Patti Smith)

- 1972: The Tooth of Crime

- 1974: Geography of a Horse Dreamer

- 1975: Action

- 1976: Angel City

- 1976: Suicide in B Flat

- 1977: Inacoma

- 1978: Curse of the Starving Class

- 1978: Buried Child

- 1978: Tongues (with Joseph Chaikin)

- 1979: Seduced: a Play in Two Acts

- 1980: True West

- 1981: Savage/Love (with Joseph Chaikin)

- 1983: Fool for Love

- 1985: A Lie of the Mind

- 1987: A Short Life of Trouble

- 1987: The War in Heaven

- 1991: States of Shock

- 1993: Simpatico

- 1996 Tooth of Crime (Second Dance)

- 1998: Eyes for Consuela

- 2000: The Late Henry Moss

- 2004: The God of Hell

- 2007: Kicking a Dead Horse

- 2009: Ages of the Moon

- 2012: Heartless

- 2014: A Particle of Dread (Oedipus Variations)

- Collections

- 1973: Hawk Moon, PAJ Books; ISBN 0-933826-23-0

- 1983: Motel Chronicles, City Lights; ISBN 0-87286-143-0

- 1984: Seven Plays, Dial Press, 368 pages; ISBN 0-553-34611-3

- 1984: Fool for Love and Other Plays, Bantam Books, 320 pages; ISBN 0-553-34590-7

- 1996: The Unseen Hand: and Other Plays, Vintage Books, 400 pages; ISBN 0-679-76789-4

- 1996: Cruising Paradise, Vintage Books, 255 pages; ISBN 0-679-74217-4

- 2003: Great Dream of Heaven, Vintage Books, 160 pages; ISBN 0-375-70452-3

- 2004: Rolling Thunder Logbook, Da Capo Press, 176 pages (reissue); ISBN 0-306-81371-8

- 2004: Day out of Days: Stories, Knopf, 304 pages; ISBN 978-0-307-26540-1

- 2013: Two Prospectors: The Letters of Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark, University of Texas Press, 400 pages; ISBN 978-0-292-76196-4

- Novels

Filmography

Awards and nominations

See also

References

- ↑ Shewey, Don (1997). Sam Shepard. Perseus Books Group. ISBN 9780306807701. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ Wetzsteon, Ross (November 11, 1984). "The Genius of Sam Shepard". New York. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ Wim Wenders on Sam Shepard Archived August 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Video (in French), Institut National de l'Audiovisuel, 1984.

- ↑ Bloom, Harold (2009). Harold Bloom's Major Dramatists: Sam Shepard. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438116464. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- 1 2 Deb, Sopan. "Sam Shepard, Pulitzer-Winning Playwright and Actor, Is Dead at 73". The New York Times (July 31, 2017). Archived from the original on July 31, 2017.

- 1 2 Harold Bloom, ed., Sam Shepard, p. 11 Archived June 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 10, 2016

- 1 2 O'Mahony, John (October 11, 2003). "The write stuff". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017.

- ↑ "Sam Shepard biography". Film Reference. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ↑ Shirley, Don (January 14, 1979). "Searching for Sam Shepard". Washington Post. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- 1 2 Botting, Gary (1972). The Theatre of Protest in America. Harden House. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: 'Two One-Act Plays by Sam Shepard' (1965)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Times Square, Melodrama Play, and Futz (1967)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Unseen Hand, The (1969)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: 'Two by Sam Shepard' (1970)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Shaved Splits (1970)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Melodrama Play (1971)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Unseen Hand, The (1981)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Tooth of Crime, The (1983)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Superstitions and The Sad Lament of Pecos Bill on the Eve of Killing His Wife (1983)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Tongues and Skins (1984)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Geography of a Horse Dreamer (1985)". Accessed August 29, 2018.

- ↑ "Sam Shepard and Identity". Archived from the original on December 6, 2015.

- ↑ San Rafael Daily Independent Journal Archives, Aug 19, 1963, p. 13. "THE FLYING Y RANCH above Mill Valley is a popular place throughout the year with 4-H groups and Southern Marin Horsemen's Assn. members..."

- ↑ "Where is Homestead Valley?". Mill Valley Historical Society. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ↑ "4-H Valley Riders". Mill Valley Historical Society. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Jesse Shepard". Sam Shepard. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Sam Shepard's kid in writing game / Like his father's, Jesse's stories are filled with horses". SF Gate. February 21, 2003. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Sam Shepard, playwright and actor, dead at 73". CNN. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017.

- 1 2 "Sam Shepard: US actor and playwright dies aged 73". BBC. July 31, 2017. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Broadway to Dim Lights in Memory of Sam Shepard". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017.

- ↑ Brantley, Ben (February 19, 2010). "THEATER REVIEW: Home Is Where the Soul Aches". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010.

- 1 2 Healy, Patrick (February 13, 2010). "Getting Faster With Age: Sam Shepard's New Velocity". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ↑ Kirn, Walter (January 17, 2010). "Sam Shepard: The Highwayman – Review of Day out of Days: Stories by Sam Shepard". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 18, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter S" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Feature Films: 'You Were Never Here'". Backstage. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "The Sam Shepard Web Site". Sam Shepard. Archived from the original on February 25, 2017.

- ↑ "patti smith: affair w/ sam shepard". Ocean Star. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Johnson, Zach (December 19, 2011). "Rep: Jessica Lange and Sam Shepard Have Separated". Us Weekly. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ↑ Sullivan, James (April 26, 2003). "THE SCENE: Sam Shepard joins Jesse Shepard for a reading at City Lights". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ Kirn, Walter (May 13, 1996). "Tales of Two Hipsters". New York. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ Lang, Peter (2007). Dis/figuring Sam Shepard. p. 42. ISBN 9789052013527. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ Bottoms, Stephen J. (1998). The Theatre of Sam Shepard: States of Crisis. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780521587914. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ Callens, Mark (1998). Sam Shepard V8, Part 4. Taylor & Francis. p. 79. ISBN 9780203989890. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Sam Shepard Arrested – Blows It Big Time". TMZ. January 3, 2009. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ↑ "Sam Shepard Guilty of Very Drunken Driving". TMZ. February 11, 2009. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009.

- ↑ Mackie, Drew (May 26, 2015). "Actor/Playwright Sam Shepard Arrested on Drunk Driving Charges in Santa Fe". People. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015.

- ↑ DeMara, Bruce (March 7, 2013). "Shepard & Dark, a testament to friendship: review". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ Shepard, Sam; Dark, Johnny (November 2013). Two Prospectors: The Letters of Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292754225.

- ↑ Hill, Libby (July 31, 2017). "Sam Shepard, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and Oscar-nominated actor, dies at 73". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ↑ Desta, Yohana (July 31, 2017). "Sam Shepard, Prolific Playwright and Actor, Dies at 73". Vanity Fair. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ↑ "My Buddy: Patti Smith Remembers Sam Shepard". The New Yorker. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ↑ "Sam Shepard Papers, 1972–1999". Texas State University - San Marcos. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Sam Shepard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center". University of Texas at Austin. Processed by: Liz Murray (2011), Daniela Lozano (2012). Retrieved September 4, 2017.

Further reading

- Espartaco, Carlos. Eduardo Sanguinetti: The Experience of Limits, p. 96 (Ediciones de Arte Gaglianone, first published 1989). ISBN 950-9004-98-7

- Radavich, David. "Back to the (Plutonian) Midwest: Sam Shepard's The God of Hell". New England Theatre Journal 18 (2007): 95–108.

- Radavich, David. "Rabe, Mamet, Shepard, and Wilson: Mid-American Male Dramatists of the 1970s and '80s". The Midwest Quarterly XLVIII: 3 (Spring 2007): 342–58.

- Shewey, Don (1997). Sam Shepard. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80770-1.

- Ryder Howe, Benjamin; McCulloch, Jeanne; Simpson, Mona (1997). "Sam Shepard, The Art of Theater No. 12". The Paris Review (142).

- Corrigan, Michael (May 12, 2015). "Cruising Paradise with Sam Shepard". Atticus Review. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- Winters, John. Sam Shepard: a life. Berkeley, California. ISBN 9781619027084. OCLC 960836493.

External links

- Official website

- The Flying Y Ranch

- Sam Shepard on IMDb

- Sam Shepard Papers at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

- Sam Shepard at Bucknell University

- Sam Shepard at the Internet Broadway Database

- Sam Shepard at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- Works by or about Sam Shepard in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Carol Benet collection of Sam Shepard research materials, 1970–1995 Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Shepard's page on La MaMa Archives Digital Collections