Halle train collision

Location within Belgium | |

| Date | 15 February 2010 |

|---|---|

| Time | 08:28 CET (07:28 UTC) |

| Location | Buizingen, Halle |

| Coordinates | 50°44′42″N 4°15′6″E / 50.74500°N 4.25167°E |

| Country | Belgium |

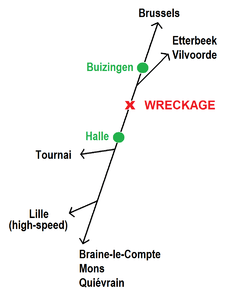

| Rail line | Line 96 (Brussels–Quévy) |

| Operator | NMBS/SNCB |

| Type of incident | Collision |

| Cause | Running of a red signal |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 2 passenger trains |

| Passengers | 250–300 passengers |

| Deaths | 19 |

| Injuries | 171, of which 35 seriously |

| Damage |

Extensive damage to rails and overhead wiring Extensive damage to first three rail carriages of both trains |

The Halle train collision (also known as the Buizingen train collision) was a collision between two NMBS/SNCB passenger trains carrying 250–300 people in Buizingen, in the municipality of Halle, Flemish Brabant, Belgium, on 15 February 2010. The accident occurred in snowy conditions at 08:28 CET (07:28 UTC), during rush hour, on railway line 96 (Brussels–Quévy) about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) from Brussels between P-train E3678 from Leuven to Braine-le-Comte (a local rush hour train) and IC-train E1707 from Quiévrain to Liège (an intercity train). A third train could come to a stop just in time to avoid getting involved.[1][2] The collision killed 19 and injured 171 people, making it the deadliest rail accident in Belgium in over fifty years.[3][4]

Three investigations were held in the aftermath of the accident: a parliamentary investigation to review railway safety, a safety investigation for the purpose of preventing future accidents and a judicial investigation whether any laws were broken. The cause of the accident was determined to be a human error on behalf of the driver of the train from Leuven, who passed a red signal without authorization. This was contested by the train driver, despite the safety investigation and the judicial investigation confirming this. Another contributing factor was the absence of TBL 1+ on the train that passed the red signal. If TBL 1+ would have been installed, the accident may have been avoided. Because of multiple difficulties, the judicial investigation lasted for years, causing the train driver, the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel (the infrastructure operator) only to be summoned to court in June 2018.

The disaster also lead to the accelerated roll-out of TBL 1+ on the entire Belgian railway network. The last NMBS/SNCB train was fitted with the system in November 2016.

Collision

The train from Leuven was heading south running on schedule to Braine-le-Comte in the normal (left-handed) direction on its track. It passed a double yellow railway signal at 08:16 am about half a kilometer ahead of Buizingen train station (the next stop of the train). A double yellow signal in Belgium means a train needs to slow down to be able to stop at the next signal (which might be red). The next signal was a few hundred meters after the Buizingen station. The train driver needed to manually confirm he saw the double yellow signal, otherwise the train would have braked automatically. At 08:26 am the train stopped in Buizingen and at 08:27 am it left the station again for its next stop, Halle station. The train passed the signal behind Buizingen station at a speed of 60 km/h whilst accelerating. It was established later that the signal was red, and that the train thus was not allowed to pass it.[3]

The train from Quiévrain was also heading north running in the normal direction on its track, but with a delay of ten minutes according to schedule. After it left Halle station, it passed a yellow-green vertical signal and slowed down to a speed of 80 km/h. A yellow-green vertical signal in Belgium means the next signal will be double yellow, but there won't be enough distance between the double yellow signal and the (potentially red) signal after it to come to a full stop. A train thus needs to start braking already before encountering the double yellow signal. The train slowed down to a speed of 40 km/h when it passed the double yellow signal. At 08:26 am, the signaller in the Brussels-South signal control center directed the train from line 96 to line 96N, causing it to pass a few railway switches and this way to cross the path of the train from Leuven. This action also automatically changed the signal in front of the first railway switch to green. The train accelerated and passed the green signal at 08:27 am with a speed of about 70 km/h.[3]

Whilst approaching the railway switches, the driver of the train from Leuven noticed the train from Quiévrain was crossing its path. He used his horn and applied emergency braking, but the train could not come to a full stop in time to avoid the accident. The train from Leuven hit the train from Quiévrain in the side (laterally) at 08:28 am. The first three carriages of both trains were severely damaged in the collision; they were either crushed or flipped on their sides. The second carriage of the train from Leuven was even forced upwards into the air over the third carriage of the train.[3][5] Eyewitnesses described the collision as "brutal", with passengers being thrown "violently" around the carriages. Some mentioned "dead bodies lying next to the tracks".[6]

The driver of a third train, train E1557 from Geraardsbergen to Brussels-South that was coming from Halle and was running on a parallel track to the other trains, saw the accident happen and applied emergency braking as well. Train E1557 came to a full stop next to the two collided trains at 08:29 am, just in time to avoid hitting them, without injuries to any of the passengers.[3]

Emergency response

The train driver of the third (non-involved) train immediately contacted Infrabel's Traffic Control to report the accident (Infrabel is Belgium's national rail infrastructure owner). Traffic Control then immediately alerted the provincial 112 emergency control center of Flemish Brabant and reported "a collision with derailment and possible deaths" to them. Traffic Control also activated its emergency procedures to halt all train traffic in the area. Just a few minutes after the accident, at 08:32 am, the emergency control center initiated its "medical intervention plan" for a mass-casualty incident. The first emergency crews arrived within minutes, given that the accident happened not too far from the Halle fire station. A number of police-, fire- and emergency medical services, alongside the Red Cross and the Civil Protection, were involved in the rescue operations. At 08:39 am the provincial governor, Lodewijk De Witte, was informed of the accident. At 09:15 am, the provincial phase of emergency management was initiated.[3]

The first responders first on the scene and one of the train conductors initially asked passengers to remain in the carriages until the power was switched off, because the carriages and ground were littered with loose overhead wires. After the emergency services assured the power was switched off, they asked the walking wounded to leave the carriages and to follow the tracks. They were taken care of in a nearby sports center in Buizingen. The more seriously injured victims were first brought to a tent from the fire service, but later a field medical post was set up at the square in front of Halle train station. Here, the victims were triaged and divided over fourteen hospitals in the area, including hospitals in Brussels. Non-injured victims were gathered in another sports center in Halle, where authorities also set up a reception center for worried friends and family members who feared a loved one was amongst the victims. A telephone number for information was also installed. The Red Cross was asked to ensure the availability of regular emergency services in areas where ambulances were dispatched from.[3][7]

Casualties

Initial reports of fatalities were somewhat confusing, with the mayor of Halle, Dirk Pieters, saying that at least 20 people had been killed in the crash, whilst other sources were quoting a death toll ranging from 8 to 25.[1][7] A more rigorous figure was provided by the provincial authorities of Flemish Brabant during a press conference on the afternoon of 15 February: a provisional death toll of 18 people (15 men and 3 women), based on bodies actually recovered from the wreckage, and 162 injured victims.[2] Rescuers early on discounted the possibility of finding more survivors still trapped in the two trains, and the search for bodies was interrupted at nightfall to resume the next morning. The recovered bodies were identified by the Belgian federal police's Disaster Victim Identification team and transported to a morgue in the Neder-Over-Heembeek military hospital, where support was also provided for the relatives of the death.[8][9]

The final death toll was determined to be 19, including the driver of the intercity train from Quiévrain. There were also 171 people injured in total. Of the injured victims, the emergency services transported 55 from the field medical post to a hospital by ambulance. 89 victims presented themselves to a hospital later that day by their own means. 11 victims were initially said to be in a "very serious" condition; later figures from the investigation classified 35 victims as "seriously injured", 44 as "moderately injured" and 92 as having only sustained minor bruising.[3]

Damage and service disruption

Train services disrupted

Immediately after the accident, all rail traffic was suspended on lines 96 (Brussels–Quévy), 94 (Halle–Tournai), 26 (Halle–Schaarbeek) and HSL 1. Consequential disruptions were expected throughout much of Wallonia (southern Belgium) and in a more limited fashion also in Flanders (northern Belgium). It took two to three days to recover human remains and perform necessary investigative acts, and a few additional days to repair the damage to adjacent tracks so those could be taken into service again. During those days, alternative bus services were provided between Halle station and Brussels-South station. After the damage to the adjacent tracks and overhead wiring was repaired, limited service could resume on those tracks.[10][11]

Because line 96 is also used by international high-speed trains leaving from Brussels for France and the United Kingdom until they can enter HSL 1 in Halle, international traffic was suspended as well and remained suspended through Tuesday 16 February. Thalys, a high-speed operator built around the line between Paris and Brussels, had to divert four of its high-speed trains in the area at the time to alternative stations. It cancelled all of its services, including trains to Amsterdam and Cologne. A limited Thalys service between Brussels and Paris resumed on the evening of 16 February, with trains leaving from Brussels passing on the single usable track at Buizingen, while trains from Paris were diverted via Ghent. Thalys services between Brussels and Cologne resumed on 17 February. Other TGV services from France to Brussels terminated at Lille-Flandres, just before the Belgian border and the last station before Brussels-South that can accommodate high-speed trains in normal service.[12][10][11]

Eurostar, which operates services through the Channel Tunnel to the United Kingdom, cancelled all its services to and from Brussels, but continued to operate its services between London and Paris and between London and Lille, the latter with delays.[13] A skeleton service of three Eurostar trains a day in each direction between London and Brussels resumed on 22 February. The trains were diverted via Ghent, causing the journey time to be lengthened. The full timetabled service resumed on Monday 1 March, two weeks after the accident.[14]

According to data from Infrabel, the accident caused 1,109 trains to be completely cancelled between 16 February and 2 March and 2,615 trains to be partially cancelled between 16 February and 11 March. The accident was also responsible for a total of 41,257 minutes (± 688 hours) of delays between 16 February and 19 March. All service disruptions were ultimately resolved on 19 March.[3]

Spontaneous strike

Further disruption was also caused on 16 February when train personnel staged an unofficial strike in protest of what they called "deteriorating working conditions", which they said could lead to accidents such as the one in Buizingen. The largest impact was in Wallonia, and international train traffic was also affected.[15]

Damage to the infrastructure

The crash caused major damage to the overhead contact system and the tracks on railway lines 96 and 96N. Railway line 26, a major freigth and commuter line, was also damaged due to debris thrown around.[3] After the recovery of human remains and the necessary investigative acts on the scene, which took two to three days, the (relatively) undamaged carriages got hauled away between Tuesday 16 and Wednesday 17 February. The removal of the wrecked train carriages started on Thursday 18 February. The carriages were completely removed on 26 February, after which Infrabel could start repairing the tracks and overhead wiring. On Monday 1 March, two weeks after the crash, the tracks and overhead wiring were repaired by Infrabel and all suspended train traffic could resume on the affected lines. However, a speed limitation of 40 km/h remained in place until the end of the week because the new tracks had to be stabilised yet. Infrabel warned the speed restriction could result in delays of 5 to 10 minutes during rush hour.[16][17]

Condolences and reactions

Domestic

Both King Albert II and prime minister Yves Leterme returned from their foreign stay to Belgium and visited the crash site the same day of the accident. Prime minister Leterme expressed his condolences with the victimes and their families, and stated that "there was a sense of defeat. First Liège, and now this". A few weeks prior, on 27 January 2010, a gas explosion in Liège killed 14 people. They were accompanied by a large delegation of ministers of the federal government and the regional governments, the CEOs of the Belgian rail companies (NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel), Brussels Royal Prosecutor Bruno Bulthé, the general commissioner of the federal police Fernand Koekelberg and governor Lodewijk De Witte. Walloon minister-president Rudy Demotte called the accident a "not just a Walloon or Flemish drama, but a national drama". Flemish minister-president Kris Peeters was on an economic mission in San Francisco and thus could not be there, but he expressed his condolences in the name of the Flemish government, and thanked the emergency services for their quick intervention. Federal minister of Public Enterprises (responsible for the NMBS/SNCB) Inge Vervotte visited the crash site together with the other ministers of the government, and said she was "very impressed" by the wreckage. She thanked the railway workers and emergency services for their rescue efforts. Former prime minister and then European president Herman Van Rompuy also expressed his sorrow and condolences.[18][19]

Foreign

The train crash was quickly reported on in the international news media, and condolences were received from multiple foreign officials. President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso expressed his condolences with Belgium in the name of the European Commission and in his own name, and sent a letter to prime minister Leterme. French president Nicolas Sarkozy offered his condolences in the name of the French people to King Albert II and stated "he was saddened when he learned which terrible train accident struck the country with grief". He stressed the deep solidarity between both countries. Prime minister Leterme also received condolences from British prime minister Gordon Brown and Dutch prime minister Jan Peter Balkenende.[19][20]

Memorial

On Saturday 12 February 2011, a year after the crash, a bilingual French-Dutch memorial stone was unveiled on the town square of Buizingen in remembrance of the 19 killed victims. The memorial ceremony was attended by family members of the victims, members of the emergency services, mayor Dirk Pieters of Halle, federal ministers Inge Vervotte and Annemie Turtelboom, the railway CEOs and the governors of Flemish Brabant and Hainaut. Some family members expressed hope that the NMBS/SNCB and politicians would finally commit to install automatic braking systems on each train.[21]

On 15 February 2015, on the fifth anniversary of the accident, a memorial plaque with the names of the 19 killed victims on the memorial stone was unveiled during a ceremony.[22]

Cause of the accident

Initial reports

Initial reports suggested the Leuven–Braine-le-Comte train (heading south from Buizingen train station) was on the wrong track because of either the unauthorized running of a red signal or a technical failure in the railway signalling. During a press conference, governor De Witte confirmed that "the signals probably weren't correctly followed". It was also reported that the railway line itself was fitted with a safety system that would have caused a train that ran a red signal to brake automatically, but that not all trains were fitted with the system as well.[2] The CEO of the NMBS/SNCB at the time, Marc Descheemaecker, replied that it was "too early to confirm a hypothesis" and that "[we] will have to carry out a neutral enquiry", but admitted that de Witte's comments were "not unbelievable". Another possible cause was reported in Le Soir, a French-speaking Belgian daily, suggesting a fault in the electricity supply could have caused a signal failure, and hence be behind the accident.[7]

The possibility of a signal failure was quickly dismissed however, since that would have been registered in the Brussels-South signal control center. In case of a signal failure, the signal for the Quiévrain–Liège train would have been automatically changed to red as well. It was also established that the Quiévrain–Liège train followed the signals correctly.[23] The driver of the Leuven–Braine-le-Comte train, who was injured in the accident, denied he passed a red signal however. He stated the signal was green.

In the weeks following the accident, multiple irregularities occurred with the signal in which it changed from green to red. On 11 March, a train had to apply emergency braking when the signal suddenly changed to red, causing it to only come to a full stop past the signal. On 15 March this occurred again, but this time the train driver was able to stop the train ahead of the signal. According to Infrabel, this was due to a strict application of the precautionary principle, which causes a signal to change to red whenever an irregularity is detected. Infrabel also said there was no danger to passengers in either of these two incidents, but the track and signal were put out of service nonetheless until the problem was solved. A theory was suggested that these defects were caused by the electromagnetic field of trains rushing past the signal on adjacent tracks. Specifically, high-speed trains passed on those adjacent tracks.[24][25]

Running of a red signal

The safety investigation carried out by the Belgian Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents (Organisme d'Enquête sur les Accidents et Incidents Ferroviaires in French; Onderzoeksorgaan voor Ongevallen en Incidenten op het Spoor in Dutch) after the accident established that the signal passed by the Leuven–Braine-le-Comte train was red however. The investigation did not reveal any action from the signal control center that could have caused the signal to be green. Moreso, because the signaller had created a path for the train from Quiévrain that would cross the path of the train from Leuven, the interlocking system automatically switched the signal for the train from Leuven to red. The Investigation Body did not find any physical defect that could have caused the signal to be green instead of red. It did however reveal problems that could have made the signal less visible, but those were not of the nature that they could have caused the accident.[3]

The prosecutor in the judicial investigation came to the same conclusion as the Investigation Body, and charged the driver of the Leuven–Braine-le-Comte train with having involuntarily caused a train wreck, caused by the unauthorized passing of a red signal.[26]

The train driver still denied running a red signal, and held on to his testimony that the signal was green.

Absence of TBL 1+ safety system

A second important factor was that the Leuven–Braine-le-Comte train was not yet fitted with the TBL 1+ safety system. The TBL 1+ system caused a train that passed a red signal, or that approaches a red signal too fast to be able to brake in time (> 40 km/h), to apply emergency braking. The track in question was fitted with the system. If the train would have been fitted with the system as well, it thus would have automatically applied emergency braking upon approaching the red signal too fast and the accident thus may have never happened. This was identified in both the safety investigation by the Investigation Body as well as in the judicial investigation. The NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel had started to equip the trains and rail network with the TBL 1+ system in 2009, but the roll out over the entire network happened slowly. Because of this, the prosecutor charged both the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel with negligence.[3][26]

Investigations

Three separate investigations were held in the aftermath of the accident: a parliamentary inquiry, a safety investigation by the Belgian Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents and a judicial investigation by the judicial authorities in Brussels (and later Halle-Vilvoorde). The final report of the parliamentary commission that looked into the case was approved and published a year after the accident, on 3 February 2011. The report of the Investigation Body was published in May 2012. The judicial investigation however experienced significant delays due to the complicated technical aspects to the case, the transfer of the case from the Brussels prosecutor to the prosecutor of Halle-Vilvoorde, the retirement of the initial investigating judge and litigation about the language of the investigation. The case was only brought before the police tribunal of Halle in June 2018.

Parliamentary investigation

Demand for investigation

Soon after the collision happened, questions about the accident arose from politicians. The minister of Public Enterprises (responsible for the NMBS/SNCB) at the time, Inge Vervotte (CD&V), asked the Railway Safety and Interoperability Service of the Federal Public Service Mobility and Transport an overview of train protection systems from 1999 to 2010. The first decision to implement ETCS was made in 1999. Minister Vervotte wanted to track all measures regarding train safety taken since then, together with former NMBS/SNCB CEO and state secretary for Mobility at the time Etienne Schouppe (CD&V).[27]

In the Chamber of Representatives, the lower house of the Belgian Federal Parliament, opposition parties including Groen!, N-VA, Vlaams Belang and Lijst Dedecker asked for a formal parliamentary investigative commission to research the circumstances of the accident and railway safety in general. The majority parties however wanted to wait until the Infrastructure commission of the Chamber would have met on Monday 22 February, a week after the accident. In the meeting on 22 February, the three CEOs of the Belgian rail companies Luc Lallemand (Infrabel), Marc Descheemaecker (NMBS/SNCB) and Jannie Haek (NMBS/SNCB-Holding) and minister Vervotte were heard by the commission about investments in railway safety. The most important question asked was why an automatic braking system like TBL 1+ was not implemented yet across the entire rail network, nine years after the Pécrot rail crash.[28] It was eventually decided a special Chamber commission (not an investigative commission however, which has more powers) would be installed to look into the accident and railway safety in general. The end of the commission's work was initially foreseen to be before the summer of 2010.[29] The work of the commission was disrupted however by the resignation of the Leterme II government and the following general elections. The commission eventually approved its report on 3 February 2011. The report consisted of more than 300 pages and contained 109 recommendations to avoid similar accidents in the future.[30]

In its investigation, the commission also relied on reports from the Court of Audit, the European Railway Agency and other experts, made on request of the commission. The Court of Audit reviewed investments made by the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel, whilst the Agency assessed the functioning of the Railway Safety and Interoperability Service and the Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents.[31][32]

Identified shortcomings

In the report, the commission concluded that the general railway safety level in Belgium did not undergo any meaningful improvements from 1982 to 2010, unlike foreign countries and despite the deadly accidents in Aalter in 1982 and in Pécrot in 2001. The NMBS/SNCB was said to have had a reactive attitude towards safety during that period. The lack of safety improvements could not be explained by lacking investment budgets. The preference for national companies in public tenders for safety systems and the preference of the NMBS/SNCB for self-developed systems however was said to have had an impact on the speed with which systems were rolled out. Favouring national companies in public tenders was made illegal in the European Union in 1993, but the Court of Audit said that recent safety investment projects regarding GSM-R and ETCS could have been done better nonetheless.[30][33]

The parliamentary report confirmed that, even when ETCS would be fully rolled out in the future, the human factor will remain very important in railway safety. It criticized the complex hierarchy within the railway companies, preventing a proper information flow in both directions, and other occupational stress factors like a lack of punctuality, irregular working schedules and a lack of participation and autonomy as having an impact on safety. It also mentioned the rising incidence of red signals passed, from 82 in 2005 to 117 incidents in 2009 (a rise of 43%), and distraction being reported as the main cause (52%). It was said the incidents were too often analysed on an individual basis, instead of the underlying causes and trends being analysed. The existing plans of action at the time to combat the passing of red signals were said to be ineffective and with too little results. A train stopping between a double yellow signal and a red signal was mentioned as having an increased risk of running the red signal.[30]

The commission also reviewed the company culture at the rail companies, more specifically the safety culture. It was said the companies each had a proper safety policy but lacked an integrated safety culture. Safety was too often only a concern of front-line personnel instead of being subject to systemic planning and risk analysis. The further development of a complete safety culture was considered to be necessary, given the future challenges expected for the railways.[30]

Additionally, other problems cited were a problematic transposition of European directives regarding railways and rail safety into national law, insufficient resources for the Railway Safety and Interoperability Service, an unclear division of responsibilities between the Service and Infrabel and a lack of cooperation between the Service and the Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents.[30]

Recommendations

Regarding train protection systems, the commission recommended the further rollout of the TBL 1+ system as planned without any delay, which was due to be completed by 2013 for the rolling stock and 2015 for the rail infrastructure. However, an evolution to a system in line with the ERTMS specifications that allows full control over a train's speed was deemed to be necessary. In this regard, the rollout of ETCS1 was to be continued as well. The commission also stated all locomotives fitted with ETCS1 had to be equipped with ETCS2, and the further rollout of ETCS2 had to be studied and considered.[30]

Regarding the factor of human errors in railway safety, the commission underscored the need for improvement in the railway companies' human resources management, more specifically in the recruitment of new personnel and the training of both new and existing personnel. To reduce stress on train drivers, more attention needs to be given to their scheduling, the communication with them and their participation in the company. Regarding the passing of red signals in particular, the commission stated the need to replace badly visible signals or to install repeater signals. A better feedback culture needed to be created within the railway companies to report problems such as bad signalling. A thorough analysis has to be made of each incident of a red signal passed, as part of a proactive safety culture. Procedures on how to handle the passing of a red signal need to focus less on the punishment of the train driver and more on how to avoid similar incidents in the future.[30]

Regarding safety culture, the commission warned that a one-sided focus on safety technology would be insufficient, and that safety always has to be approached in an integrated way. It recommended an audit of and the improvement of safety culture across the board. More thorough risk inventarisation, risk assessment and follow-up on measures taken was deemed necessary. More participation of front-line personnel in railway safety was to be encouraged, and the company hierarchy was to be simplified to improve the flow of information regarding safety.[30]

Other recommendations included improvements in the independence, the financing, the staffing and the functioning of the Railway Safety and Interoperability Service and the Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents, and the development of measurable safety indicators.[30]

Follow-up

The European Railway Agency published a report in 2013 on the corrective measures taken by Railway Safety and Interoperability Service and the Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents in response to the parliamentary recommendations.[34]

Safety investigation

The Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents (Organisme d'Enquête sur les Accidents et Incidents Ferroviaires in French; Onderzoeksorgaan voor Ongevallen en Incidenten op het Spoor in Dutch) carries out safety investigations into railway accidents for the purpose of improving general railway safety. Their investigations are explicitly not meant to cast guilt or blame upon anyone, which remains the responsibility of the judicial authorities. The Investigation Body published its report in May 2012.[3]

Running of a red signal

The investigation by the Investigation Body did not reveal any action from the signaller in the signal control center that could have caused the signal to be green for the train from Leuven. Moreso, because the signaller had created a path for the train from Quiévrain that would cross the path of the train from Leuven, the interlocking system automatically switched the signal for the train from Leuven to red. The Investigation Body did not find any physical defect that could have caused the signal to be green instead of red, and therefor considers it as established that the signal was in fact red. The Investigation Body also analysed the possible reasons as to why the red signal could have been passed by the driver. It found that there were problems that could have made the signal less visible, but those were not of the nature that they could have caused the running of the signal. It also did not find any physical or physiological condition that could have explained a poor perception of the color of the signal. Nor was distraction, abnormal fatigue, time pressure or stress found to be a plausible cause, aside from the fact that the driver had had a short night's sleep. A possible explanation could be found in the psychological and more specifically the cognitive aspects of the train driver's activities in the operational context in which he found himself to be. This way, the train driver could have erroneously assumed the signal was green because of the combination of a slightly lessened attention due to the driver's short night's sleep and a routine reaction to the signal that the train's doors were closed. The Investigation Body made recommendations to decrease the risk of such situations in the future.[3]

Automatic protection systems

The risk of unauthorized passages of red signals was not an unknown scenario however; there is always a certain risk of such situations occurring due to complex psychological reasons and shortcomings in human reliability on which mankind will never fully have a grasp. Because of this, the Investigation Body stated that the only solution is the adoption of automatic train protection systems: systems that can monitor a train's speed and apply the brakes automatically, such as the TBL 1+ system that was being rolled out since 2009. Aside from such systems, a corrective system should also be implemented for the cases where a red signal is passed. Such corrective systems did not exist yet at the time. In more general terms, the Investigation Body stated more attention should go to a corrective system for all situations in which there is a loss of control, and to passive safety.[3]

Safety culture

The Belgian railway companies were already aware of the impossibility of eliminating human errors and of the need of technological solutions to combat red signals being passed for almost a decade. However, this knowledge did not sufficiently translate in concrete actions being taken. As reasons for this, the Investigation Body mentioned the cultural heritage of the railway companies, which was characterised by a reactive attitude and a normative response to accidents focused on ground personnel. The common cultural perception was that the main responsibility lied with the train drivers, and that the problem of red signals being passed could thus be solved through training and punishments, amongst other things. The importance of monitoring systems and automatic braking in improving railway safety was not sufficiently recognised, and the eventual recognition of its importance was not sufficient to also introduce such systems quickly and effectively. The Investigation Body also found a certain weakness in the designated National Safety Authority (the Railway Safety and Interoperability Service of the Federal Public Service Mobility and Transport), which caused an important shift in the responsibility for safety management to Infrabel, the national railway infrastructure operator. Nevertheless, the Railway Safety and Interoperability Service was the only independent service that could mandate an integrated approach to safety. This weakness was the result of important delays in meeting deadlines of regulatory requirements. The approval and management of risk management methods and the systemic and organisational analysis of incidents remained incomplete, despite the application of the relevant European Union directive.[3]

Accelerated roll-out of TBL 1+

Infrabel and the SNCB/NMBS proposed a plan for the accelerated roll-out of TBL 1+ on the level of the rolling stock by the end of 2013, and on the level of the railway infrastructure by the end of 2015. This plan was considered to be an acceptable catch up by the Investigation Body. However, because TBL 1+ does not allow the complete monitoring of a train, the Investigation Body noted that this catch up could only serve as a transitional measure towards the implementation of ETCS by the two companies.[3]

Judicial investigation and indictments

Opening of the investigation

The Brussels Royal Prosecutor, Bruno Bulthé, opened an investigation and announced the appointment of an investigating judge from the Dutch-speaking tribunal of first instance of Brussels, Jeroen Burm, to oversee the judicial enquiry. The investigating judge delegated the investigation to the railway police and appointed two boards of experts: a medicolegal board and a technical board of five experts, including engineers and computer scientists, to research all possible causes of the accident. The first report of the technical board was ready two years later, but in March 2013 the judge requested further technical investigation. The additional report was finished in February 2014. A month later, the case was transferred to the newly created Halle-Vilvoorde prosecution office as a result of the judicial reform that came into force in 2014 following the sixth Belgian state reform. The Halle-Vilvoorde prosecutor concluded that there were sufficient indications of guilt and asked the investigating judge in June 2014 to hear and if necessary indict the (surviving) train driver of the train driving to Braine-le-Comte, the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel.[26] The train driver and representatives of the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel were heard in September 2014 and formally indicted by the investigating judge.[35]

Delays in the investigation

In 2015 however, the investigating judge retired, causing the case to be taken over by a new judge. The train driver also asked for a French translation of certain documents, which he received from the railway police in March 2015. In March 2015, the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel also submitted their remarks to the technical investigation, and their representatives were again interrogated by the railway police in June 2015. In July 2015, the train driver's defence petitioned the tribunal to hold the investigation in French rather than Dutch and to transfer the case to a French-speaking judge, since that's the language the train driver speaks. In Belgium, the use of language in public affairs is a sensitive topic and is extensively regulated. The tribunal rejected, and an appeal was struck down in October 2015 as well. A cassation appeal was lodged with the Court of Cassation, the Belgian supreme court, but was later retracted by the train driver in January 2016. The train driver was finally heard in July 2016. In the mean time, many other witnesses were heard as well, and the last processes-verbal of the hearings were added to the case in September 2016. The investigating judge rounded up the investigation at the end of September 2016 and sent it back to the Halle-Vilvoorde prosecution office to decide on whether and who to prosecute.[26]

Final charges

After the long delays in the case, the Halle-Vilvoorde prosecutor formally asked the Brussels tribunal of first instance in November 2016 to summon the train driver, the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel to the police tribunal of Halle, which has jurisdiction over traffic offences. According to the prosecutor it was established that the train driver ignored a red signal light, which laid at the basis of the crash, despite the train driver contesting this. In addition, the prosecutor stated that Infrabel and the NMBS/SNCB were guilty of negligence with regards to respectively the safety of rail infrastructure and the operating of trainsets without appropriate safety systems.[26] The tribunal was to decide on the summons on 24 April 2017.[36] At the hearing however, a request was made for additional investigation. A new hearing was planned for March 2018.[37]

In March 2018, the tribunal of first instance in Brussels definitively decided that the driver, the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel would be held to account before the police tribunal of Halle. The train driver's defence announced that it would ask the police tribunal to have the case tried in French instead of Dutch.[38]

Court trial

The opening session of the case before the police tribunal was held on 5 June 2018. Due to the large number of people expected, the tribunal exceptionally held session in a nearby community cultural centre. Before the start of the trial, 65 people had made themselves known to the investigating judge as civil parties to the case. In the Belgian justice system, people who believe they have suffered damage as the result of a crime can become civil parties to the case and ask for compensation during the trial. During the opening session, an additional 25 people made themselves known as civil parties, bringing the total number of civil parties to 90. As announced, the train driver's defence asked for a language change to French, to which the prosecutor objected.[39]

The police tribunal refused the language change because granting so would pose a risk of exceeding the reasonable time and the statute of limitations (which would set in in 2021). The police tribunal of Halle deemed it "unbelievable" that the police tribunal of Brussels could still try the case in 2018, because all documents (encompassing 46 cartons in total) would have to be translated to French, and because a new judge and prosecutor would have to familiarize themselves with the case. The police tribunal also blamed the indicted train driver of having tried all avenues to delay the case, including the earlier language-related litigation, which caused a delay of 34 months in total. Additionally, the police tribunal argued the "equality of arms" would be jeopardised, because the lawyers of the defence were already familiar with the case, but a new prosecutor from Brussels would never be able to become as familiar with the case as the current Halle-Vilvoorde prosecutor. The further handling of the case was postponed to 14 November 2018.[40]

Accelerated roll-out of TBL 1+

Following the accident, the NMBS/SNCB and Infrabel planned an accelerated roll-out of TBL 1+ on the level of the rolling stock (1.021 locomotives and self-propelled trains) by the end of 2013, and on the level of the railway infrastructure by the end of 2015. By the end of 2012, Infrabel planned on equipping 4,200 signals with the system, in comparison with the 650 equipped signals at the beginning of 2010.[33] In July 2011, 52% of all rolling stock had been equipped with TBL 1+, in comparison with only 2.5% at the beginning of 2010.[41]

However, it should be noted that the installation of TBL 1+ was only foreseen for signals on risky rail junctions (where there is a risk of an accident if a red signal is passed). The amount of signals at these risky junctions is about 70% of the more than 10,000 railway signals in Belgium. Signals not equipped with TBL 1+ can for example be found on freight lines.[42]

In September 2014, all national rolling stock had been equipped with TBL 1+ as planned, and Infrabel had installed the system on 93% of the signals at risky junctions. Infrabel foresaw that 99.9% of all these signals (7,573 signals in total) would be fitted with TBL 1+ by the end of 2015, as planned.[43]

However, international trains (such as the Benelux train) were exempted from the requirement to install TBL 1+. This exemption was eventually lifted, and in November 2016, the last of these trains were fitted with the system. By the end of 2016, freight operators such as B-Logistics also had fitted all their trains with TBL 1+. Since December 2016, trains without TBL 1+ are prohibited from driving on the Belgian railway network.[44]

See also

| Wikinews has related news: Train collision kills at least eighteen near Brussels, Belgium |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2010 Halle train crash. |

External links

- Summary of safety investigation report – Collision of two passenger trains in Buizingen on 15 February 2010 (Belgian Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents, May 2012)

- Verslag – De veiligheid van het spoorwegennet in België [Report – The safety of the railway network in Belgium] (Belgian Chamber of Representatives, 3 February 2011)

References

- 1 2 "Belgian train crash: Eighteen people dead in Halle". BBC News. 15 February 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Dodentol van 18 personen bevestigd" [Death toll of 18 persons confirmed]. De Standaard (in Dutch). 15 February 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "Rapport d'enquête de sécurité – La collision ferroviaire survenue le 15 février 2010 à Buizingen" [Report of the safety investigation – The train collision of 15 February 2010 in Buizingen] (PDF). www.mobilit.fgov.be (in French). Investigation Body for Railway Accidents and Incidents. May 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Treinramp bij dodelijkste in onze geschiedenis" [Train disaster one of the deadliest in our history]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). 15 February 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Death toll of Halle train crash mounts". Flandersnews.be. 15 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Graham (15 February 2010). "At Least 18 Killed In Rush Hour Train Smash". Sky News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 "La catastrophe de Buizingen, minute par minute" [The Buizingen catastrophe, minute by minute]. Le Soir (in French). 15 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 March 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "18 doden en 162 gewonden na treinramp Halle" [18 death and 162 injured after Halle train disaster]. De Morgen (in Dutch). 15 February 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Lourd bilan après la catastophe de Hal: 18 morts, 162 blessés" [Heavy bilan after the Halle catastrophe: 18 deaths, 162 injured]. RTBF Info (in French). 17 February 2010. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Le trafic ferroviaire perturbé pendant plusieurs jours" [Railway traffic disrupted for multiple days]. Le Soir (in French). 16 February 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Nog dagen vertragingen op spoor door treinramp in Halle" [Delays expected for days because of train disaster in Halle]. De Morgen (in Dutch). 15 February 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Certains Thalys circulent entre Paris et Bruxelles" [Certain Thalys trains ride between Paris and Brussels]. Le Soir (in French). 16 February 2010. Archived from the original on 19 February 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Eurostar halted for second day after Belgium rail crash". BBC News. 16 February 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Eurostar trains to fully resume between UK and Brussels". BBC News. 26 February 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Rail strike follows Belgian crash". BBC News. 16 February 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Helft dodelijke slachtoffers treinramp Halle geïdentificeerd" [Half of all fatalities of Halle train disaster identified]. Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 17 February 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Treinverkeer in Buizingen komt weer op gang" [Train traffic in Buizingen resumes again]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). 1 March 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ "Koning bezoekt de plaats van het ongeluk" [King visits scene of the accident]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). 15 February 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Koning en ministers bezoeken plaats van drama" [King and ministers visit place of drama]. De Standaard (in Dutch). 15 February 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ "Treinramp is ook wereldnieuws" [Train disaster is also world news]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). 15 February 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ "Gedenksteen voor slachtoffers treinramp Buizingen onthuld" [Memorial stone for victims of Buizingen train disaster unveiled]. Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 12 February 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Kempeneer, Freddy (15 February 2015). "Nieuwe gedenkplaat met namen 19 slachtoffers treinramp Buizingen (Foto's)" [New memorial plaque with names of 19 victims of Buizingen train disaster (Photos)]. Persinfo (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Treinbestuurder uit Leuven negeerde rood sein" [Train driver from Leuven ignored red signal]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). 16 February 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Opnieuw problemen met sein Belgische treinramp" [Again problems with signal from Belgian train disaster]. De Volkskrant (in Dutch). 16 March 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Opnieuw signalisatiefout in Buizingen" [Again signal failure in Buizingen]. Het Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). 15 March 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Onderzoek" [Investigation]. buizingen150210.be (in Dutch). Halle-Vilvoorde Prosecution Office. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "Vervotte wil overzicht beslissingen sinds 1999" [Vervotte wants an overview of decisions since 1999]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). 17 February 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Vraag naar onderzoekscommissie over Buizingen" [Demand for investigative commission into Buizingen]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). 22 February 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Commissie-Buizingen maakt werkingsafspraken" [Buizingen commission makes working agreements]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). 3 March 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Musin, Linda; Balcaen, Ronny; De Bue, Valérie; Van Den Bergh, Jef (3 February 2011). "Rapport – La sécurité du rail en Belgique/Verslag – De veiligheid van het spoorwegennet in België" (PDF). www.dekamer.be. 2nd session of the 53th legislature. Doc 53 0444/002 (2010/2011) (in French and Dutch). Belgian Chamber of Representatives. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ↑ "Assessment of Belgian NSA and NIB". www.era.europa.eu. European Union Agency for Railways. 26 October 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ "Rail security – Court of Audit's contribution to the parliamentary examination of the security conditions of the rail (in Belgium)". www.ccrek.be. Court of Audit. 11 August 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Rekenhof kritisch over veiligheidssystemen voor treinen" [Court of Audit critical about safety systems for trains]. De Morgen (in Dutch). 30 August 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ "Assessment of NSA and NIB activities in Belgium". www.era.europa.eu. European Union Agency for Railways. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ "Accident de Buizingen: la SNCB et Infrabel inculpées" [Buizingen accident: the SNCB and Infrabel indicted]. Le Soir (in French). 26 September 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "Judicial authorities want rail companies and train driver summoned". Flandersnews.be. 10 March 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "Home". buizingen150210.be (in Dutch). Halle-Vilvoorde Prosecution Office. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "Alle beschuldigden treinramp Buizingen doorverwezen naar rechtbank" [All accused in Buizingen train collision referred to court]. De Standaard (in Dutch). 30 March 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ ""Treinbestuurder treinramp Buizingen wil in eigen taal zeggen dat hij niet in fout was": openbaar ministerie verzet zich daartegen" ["Train driver from Buizingen train collision wants to say he did not make an error in his own language": public ministry objects]. Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 5 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ "Proces treinramp Buizingen moet in het Nederlands, beslist rechter" [Buizingen train disaster trial will be held in Dutch, decides judge]. Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 29 June 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ↑ "Helft NMBS-treinen uitgerust met veiligheidssysteem TBL1+" [Half of all NMBS trains equipped with TBL1+ safety system]. Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 29 July 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ "Developing safety systems". www.infrabel.be. Infrabel. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Maréchal, Gisèle (26 September 2014). "Accident de Buizingen: la SNCB et Infrabel inculpées" [Buizingen accident: the SNCB and Infrabel indicted]. Le Soir (in French). Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ↑ Arnoudt, Rik; Piessen, Maité (11 December 2016). "Alle Belgische treinen uitgerust met automatische noodrem" [All Belgian trains equipped with automatic braking]. VRT Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 16 June 2018.