Hospital

_2007-03-03.jpg)

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized medical and nursing staff and medical equipment.[1] The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emergency department to treat urgent health problems ranging from fire and accident victims to a heart attack. A district hospital typically is the major health care facility in its region, with large numbers of beds for intensive care and additional beds for patients who need long-term care. Specialized hospitals include trauma centers, rehabilitation hospitals, children's hospitals, seniors' (geriatric) hospitals, and hospitals for dealing with specific medical needs such as psychiatric treatment (see psychiatric hospital) and certain disease categories. Specialized hospitals can help reduce health care costs compared to general hospitals.[2] Hospitals are classified as general, specialty, or government depending on the sources of income received.

A teaching hospital combines assistance to people with teaching to medical students and nurses. The medical facility smaller than a hospital is generally called a clinic. Hospitals have a range of departments (e.g. surgery and urgent care) and specialist units such as cardiology. Some hospitals have outpatient departments and some have chronic treatment units. Common support units include a pharmacy, pathology, and radiology.

Hospitals are usually funded by the public sector, health organisations (for profit or nonprofit), health insurance companies, or charities, including direct charitable donations. Historically, hospitals were often founded and funded by religious orders, or by charitable individuals and leaders.[3]

Currently, hospitals are largely staffed by professional physicians, surgeons, nurses, and allied health practitioners, whereas in the past, this work was usually performed by the members of founding religious orders or by volunteers. However, there are various Catholic religious orders, such as the Alexians and the Bon Secours Sisters that still focus on hospital ministry in the late 1990s, as well as several other Christian denominations, including the Methodists and Lutherans, which run hospitals.[4] In accordance with the original meaning of the word, hospitals were originally "places of hospitality", and this meaning is still preserved in the names of some institutions such as the Royal Hospital Chelsea, established in 1681 as a retirement and nursing home for veteran soldiers.

Etymology

| Look up hospital in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

During the Middle Ages, hospitals served different functions from modern institutions. Middle Ages hospitals were almshouses for the poor, hostels for pilgrims, or hospital schools. The word "hospital" comes from the Latin hospes, signifying a stranger or foreigner, hence a guest. Another noun derived from this, hospitium came to signify hospitality, that is the relation between guest and shelterer, hospitality, friendliness, and hospitable reception. By metonymy the Latin word then came to mean a guest-chamber, guest's lodging, an inn.[5] Hospes is thus the root for the English words host (where the p was dropped for convenience of pronunciation) hospitality, hospice, hostel and hotel. The latter modern word derives from Latin via the ancient French romance word hostel, which developed a silent s, which letter was eventually removed from the word, the loss of which is signified by a circumflex in the modern French word hôtel. The German word 'Spital' shares similar roots.

The grammar of the word differs slightly depending on the dialect. In the United States, hospital usually requires an article; in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, the word normally is used without an article when it is the object of a preposition and when referring to a patient ("in/to the hospital" vs. "in/to hospital"); in Canada, both uses are found.

Types

Some patients go to a hospital just for diagnosis, treatment, or therapy and then leave ("outpatients") without staying overnight; while others are "admitted" and stay overnight or for several days or weeks or months ("inpatients"). Hospitals usually are distinguished from other types of medical facilities by their ability to admit and care for inpatients whilst the others, which are smaller, are often described as clinics.

General/Acute-Care

The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, also known as an acute-care hospital. These facilities handle many kinds of disease and injury, and normally have an emergency department (sometimes known as "accident & emergency") or trauma center to deal with immediate and urgent threats to health. Larger cities may have several hospitals of varying sizes and facilities. Some hospitals, especially in the United States and Canada, have their own ambulance service.

District

A district hospital typically is the major health care facility in its region, with large numbers of beds for intensive care, critical care, and long-term care.

In California, "district hospital" refers specifically to a class of healthcare facility created shortly after World War II to address a shortage of hospital beds in many local communities.[6][7] Even today, district hospitals are the sole public hospitals in 19 of California's counties,[6] and are the sole locally-accessible hospital within 9 additional counties in which one or more other hospitals are present at substantial distance from a local community.[6] Twenty-eight of California's rural hospitals and 20 of its critical-access hospitals are district hospitals.[7] They are formed by local municipalities, have boards that are individually elected by their local communities, and exist to serve local needs.[6][7] They are a particularly important provider of healthcare to uninsured patients and patients with Medi-Cal (which is California's Medicaid program, serving low-income persons, some senior citizens, persons with disabilities, children in foster care, and pregnant women).[6][7] In 2012, District hospitals provided $54 million in uncompensated care in California.[7]

Specialised

Types of specialised hospitals include rehabilitation hospitals, children's hospitals, seniors' (geriatric) hospitals, long-term acute care facilities and hospitals for dealing with specific medical needs such as psychiatric problems (see psychiatric hospital), certain disease categories such as cardiac, oncology, or orthopedic problems, and so forth. In Germany specialised hospitals are called Fachkrankenhaus; an example is Fachkrankenhaus Coswig (thoracic surgery).

A hospital may be a single building or a number of buildings on a campus. Many hospitals with pre-twentieth-century origins began as one building and evolved into campuses. Some hospitals are affiliated with universities for medical research and the training of medical personnel such as physicians and nurses, often called teaching hospitals. Worldwide, most hospitals are run on a nonprofit basis by governments or charities. There are however a few exceptions, e.g. China, where government funding only constitutes 10% of income of hospitals. (need citation here. Chinese sources seem conflicted about the for-profit/non-profit ratio of hospitals in China)

Specialised hospitals can help reduce health care costs compared to general hospitals. For example, Narayana Health's Bangalore cardiac unit, which is specialised in cardiac surgery, allows for significantly greater number of patients. It has 3000 beds (more than 20 times the average American hospital) and in pediatric heart surgery alone, it performs 3000 heart operations annually, making it by far the largest such facility in the world.[8][2] Surgeons are paid on a fixed salary instead of per operation; thus, the costs to the hospital drops when the number of procedures increases, taking advantage of economies of scale.[8] Additionally, it is argued that costs go down as all its specialists become efficient by working on one "production line" procedure.[2]

Teaching

A teaching hospital combines assistance to people with teaching to medical students and nurses and often is linked to a medical school, nursing school or university. In some countries like UK exists the clinical attachment system that is defined as a period of time when a doctor is attached to a named supervisor in a clinical unit, with the broad aims of observing clinical practice in the UK and the role of doctors and other healthcare professionals in the National Health Service (NHS).

Clinics

The medical facility smaller than a hospital is generally called a clinic, and often is run by a government agency for health services or a private partnership of physicians (in nations where private practise is allowed). Clinics generally provide only outpatient services.

Departments or wards

Hospitals consist of departments, traditionally called wards, especially when they have beds for inpatients, when they are sometimes also called inpatient wards. Hospitals may have acute services such as an emergency department or specialist trauma centre, burn unit, surgery, or urgent care. These may then be backed up by more specialist units such as the following:

- Emergency department

- Cardiology

- Intensive care unit

- Paediatric intensive care unit

- Neonatal intensive care unit

- Cardiovascular intensive care unit

- Neurology

- Oncology

- Obstetrics and gynaecology, colloquially, maternity ward

In addition, there is the department of nursing, often headed by a chief nursing officer or director of nursing. This department is responsible for the administration of professional nursing practice, research, and policy for the hospital. Nursing permeates every part of a hospital. Many units or wards have both a nursing and a medical director that serve as administrators for their respective disciplines within that specialty. For example, in an intensive care nursery, the director of neonatology is responsible for the medical staff and medical care while the nursing manager/director for the intensive care nursery is responsible for all of the nurses and nursing care in that unit/ward.

Some hospitals have outpatient departments and some have chronic treatment units such as behavioral health services, dentistry, dermatology, psychiatric ward, rehabilitation services, and physical therapy.

Common support units include a dispensary or pharmacy, pathology, and radiology. On the non-medical side, there often are medical records departments, release of information departments, information management (a.k.a. IM, IT or IS), clinical engineering (a.k.a. biomed), facilities management, plant ops (operations, also known as maintenance), dining services, and security departments.

History

Early examples

The earliest documented institutions aiming to provide cures were ancient Egyptian temples. In ancient Greece, temples dedicated to the healer-god Asclepius, known as Asclepieia functioned as centres of medical advice, prognosis, and healing.[9] Asclepeia provided carefully controlled spaces conducive to healing and fulfilled several of the requirements of institutions created for healing.[10] Under his Roman name Æsculapius, he was provided with a temple (291 B.C.) on an island in the Tiber in Rome, where similar rites were performed.[11]

Institutions created specifically to care for the ill also appeared early in India. Fa Xian, a Chinese Buddhist monk who travelled across India ca. A.D. 400, recorded in his travelogue that: The heads of the Vaisya [merchant] families in them [all the kingdoms of north India] establish in the cities houses for dispensing charity and medicine. All the poor and destitute in the country, orphans, widowers, and childless men, maimed people and cripples, and all who are diseased, go to those houses, and are provided with every kind of help, and doctors examine their diseases. They get the food and medicines which their cases require, and are made to feel at ease; and when they are better, they go away of themselves.[12]

The earliest surviving encyclopaedia of medicine in Sanskrit is the Charakasamhita (Compendium of Charaka). This text, which describes the building of a hospital is dated by Dominik Wujastyk of the University College London from the period between 100 B.C. and A.D. 150.[13] According to Dr. Wujastyk, the description by Fa Xian is one of the earliest accounts of a civic hospital system anywhere in the world and, coupled with Caraka's description of how a clinic should be equipped, suggests that India may have been the first part of the world to have evolved an organised cosmopolitan system of institutionally-based medical provision.[13]

According to the Mahavamsa, the ancient chronicle of Sinhalese royalty, written in the sixth century A.D., King Pandukabhaya of Sri Lanka (reigned 437 B.C. to 367 B.C.) had lying-in-homes and hospitals (Sivikasotthi-Sala) built in various parts of the country. This is the earliest documentary evidence we have of institutions specifically dedicated to the care of the sick anywhere in the world.[14][15] Mihintale Hospital is the oldest in the world.[16] Ruins of ancient hospitals in Sri Lanka are still in existence in Mihintale, Anuradhapura, and Medirigiriya.[17]

The Romans constructed buildings called valetudinaria for the care of sick slaves, gladiators, and soldiers around 100 B.C., and many were identified by later archaeology. While their existence is considered proven, there is some doubt as to whether they were as widespread as was once thought, as many were identified only according to the layout of building remains, and not by means of surviving records or finds of medical tools.[18]

Late Roman Empire and Sassanid Persia

The declaration of Christianity as an accepted religion in the Roman Empire drove an expansion of the provision of care. Following the First Council of Nicaea in A.D. 325 construction of a hospital in every cathedral town was begun. Among the earliest were those built by the physician Saint Sampson in Constantinople and by Basil, bishop of Caesarea in modern-day Turkey. Called the "Basilias", the latter resembled a city and included housing for doctors and nurses and separate buildings for various classes of patients.[19] There was a separate section for lepers.[20] Some hospitals maintained libraries and training programmes, and doctors compiled their medical and pharmacological studies in manuscripts. Thus in-patient medical care in the sense of what we today consider a hospital, was an invention driven by Christian mercy and Byzantine innovation.[21] Byzantine hospital staff included the Chief Physician (archiatroi), professional nurses (hypourgoi) and the orderlies (hyperetai). By the twelfth century, Constantinople had two well-organised hospitals, staffed by doctors who were both male and female. Facilities included systematic treatment procedures and specialised wards for various diseases.[22]

A hospital and medical training centre also existed at Gundeshapur, a major city in southwest of the Sassanid Persian Empire founded in A.D. 271 by Shapur I. A large percentage of the population were Syriacs, most of whom were Christians. Under the rule of Khusraw I, refuge was granted to Greek Nestorian Christian philosophers including the scholars of the Persian School of Edessa (Urfa) (also called the Academy of Athens), a Christian theological and medical university. These scholars made their way to Gundeshapur in A.D. 529 following the closing of the academy by Emperor Justinian. They were engaged in medical sciences and initiated the first translation projects of medical texts.[23] The arrival of these medical practitioners from Edessa marks the beginning of the hospital and medical centre at Gundeshapur.[24] It included a medical school and hospital (wēmārestān), a pharmacology laboratory, a translation house, a library and an observatory.[25] Indian doctors also contributed to the school at Gundeshapur, most notably the medical researcher Mankah. Later after Islamic invasion, the writings of Mankah and of the Indian doctor Sustura were translated into Arabic at Baghdad's House of Wisdom.[26]

Early medieval Europe

The Romans first introduced hospitals to Britain during the early Anglo-Saxon period. During this period, hospitals were mainly confined to the domestic household or existed as small, military hospitals with the function of caring to the sick, travellers, and of the long-term infirm. During the Early Middle Ages (476\529–800) and the middle time period (ca. 800–1100), the rise of Christianity had a great effect on the practice of medicine. Church-sponsored hospitals began to appear already after A.D. 350, but they primarily furnished bed and board and seldom ventured into actual treatment. Over the next seven centuries, the hospitals gradually passed from Church to monastic control. Soon many Christian monasteries became centers of accumulation of the medical knowledge and practical experience in Europe.

Around 529 A.D. St. Benedict of Nursia (480-543 A.D.), later a Christian saint, the founder of western monasticism and the Order of St. Benedict, today the patron saint of Europe, established the first monastery in Europe (Monte Cassino) on a hilltop between Rome and Naples, that became a model for the Western monasticism and one of the major cultural centers of Europe throughout the Middle Ages, where he wrote the "Rule", containing directions for monks and Christians. The Rule of Saint Benedict is one of the most important written works in the shaping of Western civilian society because it included a written constitution, authority limited by law, and a degree of democracy. Besides, it mandated the moral obligations to care for the sick. In Monte Cassino St. Benedict founded a hospital that is considered today to have been the first hospital in Europe of the new era. There Benedictine monks took care of the sick and wounded according to the Benedict's Rule. The monastic routine called for hard work. The care of the sick was such an important duty that those caring for them were enjoined to act as if they served Christ directly. Benedict founded twelve communities for monks at nearby Subiaco (about 64 km to the east of Rome), where hospitals were settled too as adjuncts to the monasteries in order to provide charity and care for soldiers and patients. Since that time the Benedictines were very involved in healing and caring for the sick and dying, so in many cases early Medieval medicine was closely connected with Christianity and the Benedictines in particular. This is why very often the early Middle Ages are called "the Benedictine centuries".

Medieval Islamic world

_-_TIMEA.jpg)

The earliest general hospital was built in 805 in Baghdad by Harun Al-Rashid.[27][28] By the tenth century, Baghdad had five more hospitals, while Damascus had six hospitals by the 15th century and Córdoba alone had 50 major hospitals, many exclusively for the military.[29] Some of the prominent early Islamic hospitals are believed to have been founded with the assistance of Christians such as Jibrael ibn Bukhtishu from Gundeshapur;[30][31] there is no evidence to associate the construction of the earliest hospital with Christian physicians from Gondeshapur, but they may have played a role in the function of the first hospital in Baghdad.[32]

Compared to contemporaneous Christian institutions, which were poor and sick relief facilities offered by some monasteries, the Islamic hospital was a more elaborate institution with a wider range of functions. In Islam, there was a moral imperative to treat the ill regardless of financial status. Islamic hospitals tended to be large, urban structures, and were largely secular institutions, many open to all, whether male or female, civilian or military, child or adult, rich or poor, Muslim or non-Muslim. The Islamic hospital served several purposes, as a center of medical treatment, a home for patients recovering from illness or accidents, an insane asylum, and a retirement home with basic maintenance needs for the aged and infirm.[32]

The typical hospital was divided into departments such as systemic diseases, surgery and orthopedics with larger hospitals having more diverse specialties. "Systemic diseases" was the rough equivalent of today's internal medicine and was further divided into sections such as fever, infections and digestive issues. Every department had an officer-in-charge, a presiding officer and a supervising specialist. The hospitals also had lecture theaters and libraries. Hospitals staff included sanitary inspectors, who regulated cleanliness, and accountants and other administrative staff.[29] The hospitals were typically run by a three-man board comprising a non-medical administrator, the chief pharmacist, called the shaykh saydalani, who was equal in rank to the chief physician, who served as mutwalli (dean).[33] Medical facilities traditionally closed each night, but by the 10th century laws were passed to keep hospitals open 24 hours a day.[34]

For less serious cases, physicians staffed outpatient clinics. Cities also had first aid centers staffed by physicians for emergencies that were often located in busy public places, such as big gatherings for Friday prayers to take care of casualties. The region also had mobile units staffed by doctors and pharmacists who were supposed to meet the need of remote communities. Baghdad was also known to have a separate hospital for convicts since the early 10th century after the vizier ‘Ali ibn Isa ibn Jarah ibn Thabit wrote to Baghdad's chief medical officer that "prisons must have their own doctors who should examine them every day". The first hospital built in Egypt, in Cairo's Southwestern quarter, was the first documented facility to care for mental illnesses while the first Islamic psychiatric hospital opened in Baghdad in 705.[35][29]

Hospitals in this era were the first to require medical diplomas to license doctors.[36] The licensing test was administered by the region's government appointed chief medical officer. The test had two steps; the first was to write a treatise, on the subject the candidate wished to obtain a certificate, of original research or commentary of existing texts, which they were encouraged to scrutinize for errors. The second step was to answer questions in an interview with the chief medical officer. Physicians worked fixed hours and medical staff salaries were fixed by law. For regulating the quality of care and arbitrating cases, it is related that if a patient dies, their family presents the doctor's prescriptions to the chief physician who would judge if the death was natural or if it was by negligence, in which case the family would be entitled to compensation from the doctor. The hospitals had male and female quarters while some hospitals only saw men and other hospitals, staffed by women physicians, only saw women.[29] While women physicians practiced medicine, many largely focused on obstetrics.[37]

Hospitals were forbidden by law to turn away patients who were unable to pay.[34] Eventually, charitable foundations called waqfs were formed to support hospitals, as well as schools.[34] Part of the state budget also went towards maintaining hospitals.[29] While the services of the hospital were free for all citizens[34] and patients were sometimes given a small stipend to support recovery upon discharge, individual physicians occasionally charged fees.[29] In a notable endowment, a 13th-century governor of Egypt Al Mansur Qalawun ordained a foundation for the Qalawun hospital that would be free for patients and contain a mosque, a library for doctors and a pharmacy[38] and the hospital is used today for ophthalmology.[29] The hospital had accommodation for 8,000 people - [39] "it served 4,000 patients daily."[40]

Late medieval Europe

The Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, founded in 1099 (The Knights of Malta) itself has - as its raison d’être - the founding of a hospital for pilgrims to the Holy Land. In Europe, Spanish hospitals are particularly noteworthy examples of Christian virtue as expressed through care for the sick, and were usually attached to a monastery in a ward-chapel configuration, most often erected in the shape of a cross. This style reached a high point during the hospital building campaign of Portuguese St. John of God in the sixteenth-century, the founder of the Hospitaller Order of the Brothers of John of God.[41]

Soon many monasteries were founded throughout Europe, and everywhere there were hospitals like in Monte Cassino. By the 11th century, some monasteries were training their own physicians. Ideally, such physicians would uphold the Christianized ideal of the healer who offered mercy and charity towards all patients and soldiers, whatever their status and prognosis might be. In the 6th–12th centuries the Benedictines established lots of monk communities of this type. And later, in the 12th–13th centuries the Benedictines order built a network of independent hospitals, initially to provide general care to the sick and wounded and then for treatment of syphilis and isolation of patients with communicable disease. The hospital movement spread through Europe in the subsequent centuries, with a 225-bed hospital being built at York in 1287 and even larger facilities established at Florence, Paris, Milan, Siena, and other medieval big European cities.

In the North during the late Saxon period, monasteries, nunneries, and hospitals functioned mainly as a site of charity to the poor. After the Norman Conquest of 1066, hospitals are found to be autonomous, freestanding institutions. They dispensed alms and some medicine, and were generously endowed by the nobility and gentry who counted on them for spiritual rewards after death.[42] In time, hospitals became popular charitable houses that were distinct from both English monasteries and French hospitals.

The primary function of medieval hospitals was to worship to God. Most hospitals contained one chapel, at least one clergyman, and inmates that were expected to help with prayer. Worship was often a higher priority than care and was a large part of hospital life until and long after the Reformation. Worship in medieval hospitals served as a way of alleviating ailments of the sick and insuring their salvation when relief from sickness could not be achieved.[43][44]

The secondary function of medieval hospitals was charity to the poor, sick, and travellers. Charity provided by hospitals surfaced in different ways, including long-term maintenance of the infirm, medium-term care of the sick, short-term hospitality to travellers, and regular distribution of alms to the poor.[43]:58 Though these were general acts of charity among medieval hospitals, the degree of charity was variable. For example, some institutions that perceived themselves mainly as a religious house or place of hospitality turned away the sick or dying in fear that difficult healthcare will distract from worship. Others, however, such as St. James of Northallerton, St. Giles of Norwich, and St. Leonard of York, contained specific ordinances stating they must cater to the sick and that "all who entered with ill health should be allowed to stay until they recovered or died".[43]:58

The tertiary function of medieval hospitals was to support education and learning. Originally, hospitals educated chaplains and priestly brothers in literacy and history; however, by the 13th century, some hospitals became involved in the education of impoverished boys and young adults. Soon after, hospitals began to provide food and shelter for scholars within the hospital in return for helping with chapel worship.[43]:65

Three well-documented medieval European hospitals are St. Giles in Norwich, St. Anthony's in London, and St. Leonards in York.[45] St. Giles, along with St. Anthony's and St. Leonards, were open ward hospitals that cared for the poor and sick in three of medieval England's largest cities.[45]:23 The study of these three hospitals can provide insight into the diet, medical care, cleanliness and daily life in a medieval hospital of Europe.

St Giles, Norwich

Discrepancies exist among sources regarding the founding of St. Giles of Norwich, or the "Great Hospital" as it is known today. Some sources maintain that it was founded in 1246.[43]:65[44]:140 [46] Other sources state that it was founded in 1249.[45]:23 Though the date may be debatable, it seems agreed upon that The Great Hospital was founded by Walter Suffield, a Bishop known to be very liberal to the poor especially in the city of Norwich.[47] St Giles provided thirty beds and maintained within its ten-acre precinct, many meadows courtyards, ponds, and fruit trees until the late fifteenth century.[45]:23, 34 The hospital cultivated many productive gardens abundant in apples, leeks, garlic, onions and honey. The gardens were so productive that surplus goods were sold on the open market. St Giles of Norwich owned six manors and advowson of eleven churches.[45]:34

St Giles was unique in that food was provided for children who were getting free education elsewhere.[47]:27 It is also noted that St Giles arranged for seven poor scholars to receive board at the hospital during their term at Norwich School.[43]:65 Accommodations of early medieval hospitals were frequently communal. For example, in St Giles, the master and brothers ate in the common hall while sisters ate by themselves.[43]:90 St Giles hospital was a complex building that housed a community of clergy with cloister and residential accommodation, a hospital and a parish church. St Giles was also wealthy enough to maintain its own kitchen and staff. This allowed poor men to receive a dish of meat, fish, eggs or cheese in addition to the customary daily ration of bread and drink.[43]:122

St. Anthony's, London

St. Anthony's was erected in the thirteenth century (some time before 1254), in the heart of London on Threadneedle Street, atop the less than ideal site of a Jewish synagogue.[43]:43,88 [45]:23 The chapel of St. Anthony's was built in 1310 without permission of the bishop of London. To prevents its degradation, the hospital petitioned for a chapel on the bishops terms.[43]:88 Unlike St. Giles, there was insufficient land at St. Anthony's, London, for recreation or food production. As a result, herbs or 'erbys' and vegetables had to be bought on a daily basis for consumption by the entire community.[46]:178 Accounts of foreign expenses at St. Anthony's also show the purchase of various spices, often with intrinsic medicinal qualities that could alter the level of heat and moisture within the body. Some of the spices bought include, saffron, cloves, ginger, cinnamon, lavender, pepper and mustard.[45]:35 The amount spent on herbs, produce, and spices were far surpassed by the amount spent on fish and meat.

According to quarterly expenditure reports, fifty-eight percent of the quarterly budget was spent on meat, thirty-four percent on fish, three percent on pottage, two percent on dairy, one percent herbs and one percent on eggs.[45]:33 The unusually detailed records of diet and expenditures at St. Anthony's have revealed that the diet of the clerical establishment ('the hall') and the diets of the almsmen, patients and children ('the hospital') were quite different and class-based.[46]:179 During a typical week, "the entire community shared dishes of pottage, veal, mutton and eggs; the hall alone consumed pork, ribs of roast beef, duck, fresh salmon and eels; and the hospital was supplied with mutton, plaice and haddock."[45]:41 It is clear that the hall, or more wealthy, enjoyed extravagant meals of meat and fish, while the hospital, the patients and the poor, were fed simpler and cheaper food.

In addition to its reputation of spending lavishly on food, St. Anthony's was famous for its grammar school, choir and pigs, which roamed freely among the streets identified by bells.[45]:23 Pigs on sale in London, which were considered by officials to be unfit for food were handed over to St. Anthony's. The pigs were fed through charity or by scavenging and later, when their condition improved, they were then taken by the hospital for use as food for the poor or sick.[43]:122

As mentioned, medieval hospitals became concerned in education and in the feeding and housing of students as early as the thirteenth century. In 1441, John Carpenter, the master of St. Anthony London, was able to finance a grammar school whose teachings were without fees to any student. This was the first source of free education in London and remained one of London's leading schools for one hundred years following its founding.[43]:144

In 1449, St. Anthony's received a handsome legacy for the support of a clerk to train scholars in both polyphony and plainsong. St. Anthony's became so famous for its choir that in 1469, the royal minstrels set up a fraternity at the hospital so they may also study music.[46]:125

St Leonards, York

St Leonard's was one on England's largest and richest hospitals with a primary purpose of caring for the poor, the sick, the old and infirm.[45]:24 It maintained 200 beds and in its prosperous days, "maintained up to eighteen clergy, 16 sister and female servants, 30 choristers, 10 private boarders (corrodarians) and between 144 and 240 poor sick people."[43]:36 Additionally, during Easter of 1370, records show accommodation of 224 sick and poor in the infirmary and 23 children in the orphanage.[47]:156

The records of St Leonard provide the best details of daily hospital worship and patient life. In 1249, for example, matins and lauds were said in the morning hours of darkness, followed by mass of the Virgin Mary held by members of the clergy. The "lesser hours and mass of the day were said at mid-morning, vespers in the afternoon and compline in the early evening after supper." [43]:50, 52 Sisters at St. Leonard's were instructed to feed the poor and the sick, wash them, and lead them around the grounds.[45]:43 Although the food given to the sick were the simple, and often quite cheap, daily provisions, sisters were allowed to distribute special food if they were very ill.[43]:62

At St Leonard's, charity and care for the sick was not only given to inmates of the hospitals, but also to the poor in other neighboring institutions as well as inmates of local leper houses.[43]:63 Additionally, one or two of the chaplains at St Leonard's were instructed to "minister spiritually to the poor by speaking consoling words, hearing confessions, and administering the sacraments".[43]:80

Early modern and Enlightenment Europe

In Europe the medieval concept of Christian care evolved during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries into a secular one. In England, after the dissolution of the monasteries in 1540 by King Henry VIII, the church abruptly ceased to be the supporter of hospitals, and only by direct petition from the citizens of London, were the hospitals St Bartholomew's, St Thomas's and St Mary of Bethlehem's (Bedlam) endowed directly by the crown; this was the first instance of secular support being provided for medical institutions.

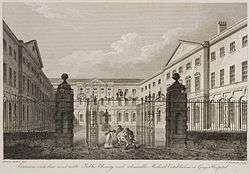

The voluntary hospital movement began in the early 18th century, with hospitals being founded in London by the 1720s, including Westminster Hospital (1719) promoted by the private bank C. Hoare & Co and Guy's Hospital (1724) funded from the bequest of the wealthy merchant, Thomas Guy.

Other hospitals sprang up in London and other British cities over the century, many paid for by private subscriptions. St Bartholomew's opened in London in 1730, and the London Hospital in 1752.

These hospitals represented a turning point in the function of the institution; they began to evolve from being basic places of care for the sick to becoming centres of medical innovation and discovery and the principal place for the education and training of prospective practitioners. Some of the era's greatest surgeons and doctors worked and passed on their knowledge at the hospitals.[48] They also changed from being mere homes of refuge to being complex institutions for the provision of medicine and care for sick. The Charité was founded in Berlin in 1710 by King Frederick I of Prussia as a response to an outbreak of plague.

The concept of voluntary hospitals also spread to Colonial America; the Bellevue Hospital Center opened in 1736; the Pennsylvania Hospital opened in 1752, New York Hospital in 1771, and Massachusetts General Hospital in 1811. When the Vienna General Hospital opened in 1784 (instantly becoming the world's largest hospital), physicians acquired a new facility that gradually developed into one of the most important research centres.[49]

Another Enlightenment era charitable innovation was the dispensary; these would issue the poor with medicines free of charge. The London Dispensary opened its doors in 1696 as the first such clinic in the British Empire. The idea was slow to catch on until the 1770s, when many such organisations began to appear, including the Public Dispensary of Edinburgh (1776), the Metropolitan Dispensary and Charitable Fund (1779) and the Finsbury Dispensary (1780). Dispensaries were also opened in New York 1771, Philadelphia 1786, and Boston 1796.[50]

The Royal Naval Hospital, Stonehouse, Plymouth, was a pioneer of hospital design in having "pavilions" to minimize the spread of infection. John Wesley visited in 1785, and commented "I never saw anything of the kind so complete; every part is so convenient, and so admirably neat. But there is nothing superfluous, and nothing purely ornamented, either within or without." This revolutionary design was made more widely known by John Howard, the philanthropist. In 1787 the French government sent two scholar administrators, Coulomb and Tenon, who had visited most of the hospitals in Europe.[51] They were impressed and the "pavilion" design was copied in France and throughout Europe.

19th century

English physician Thomas Percival (1740–1804) wrote a comprehensive system of medical conduct, 'Medical Ethics, or a Code of Institutes and Precepts, Adapted to the Professional Conduct of Physicians and Surgeons (1803) that set the standard for many textbooks.[52] In the mid-19th century, hospitals and the medical profession became more professionalised, with a reorganisation of hospital management along more bureaucratic and administrative lines. The Apothecaries Act 1815 made it compulsory for medical students to practise for at least half a year at a hospital as part of their training.[53]

Florence Nightingale pioneered the modern profession of nursing during the Crimean War when she set an example of compassion, commitment to patient care and diligent and thoughtful hospital administration. The first official nurses' training programme, the Nightingale School for Nurses, was opened in 1860, with the mission of training nurses to work in hospitals, to work with the poor and to teach.[54] Nightingale was instrumental in reforming the nature of the hospital, by improving sanitation standards and changing the image of the hospital from a place the sick would go to die, to an institution devoted to recuperation and healing. She also emphasised the importance of statistical measurement for determining the success rate of a given intervention and pushed for administrative reform at hospitals.[55]

By the late 19th century, the modern hospital was beginning to take shape with a proliferation of a variety of public and private hospital systems. By the 1870s, hospitals had more than trebled their original average intake of 3,000 patients. In continental Europe the new hospitals generally were built and run from public funds. The National Health Service, the principal provider of health care in the United Kingdom, was founded in 1948. During the nineteenth century, the Second Viennese Medical School emerged with the contributions of physicians such as Carl Freiherr von Rokitansky, Josef Škoda, Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra, and Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis. Basic medical science expanded and specialisation advanced. Furthermore, the first dermatology, eye, as well as ear, nose, and throat clinics in the world were founded in Vienna, being considered as the birth of specialised medicine.[56]

20th century and beyond

By the late 19th and the beginning 20th century, medical advancements such as anesthesia and sterile techniques that could make surgery less risky, and availability of more advanced diagnostic devices such as X-rays continued to make hospitals a more attractive option for treatment. The number of hospitalizations in the United States continued to grow and reached its peak in 1981 with 171 admissions per 1000 Americans and 6933 hospitals.[57]

This trend, however, has been reversed since then, with the rate of hospitalization falling by more than %10 and the number of hospitals shrinking to 5534 in 2016 compared to 1981 in the United States[58]. Among the reasons for this are the increasing availability of more complex care elsewhere such as at home or at the physicians' offices and also the less therapeutic and more life-threatening image of the hospitals in the eyes of the public[59].[57]

Funding

In the modern era, hospitals are either funded by the government of the country in which they are situated, or survive financially by competing in the private sector (a number of hospitals also are still supported by the historical type of charitable or religious associations).

In the United Kingdom for example, a relatively comprehensive, "free at the point of delivery" health care system exists, funded by the state. Hospital care is thus relatively easily available to all legal residents, although free emergency care is available to anyone, regardless of nationality or status. As hospitals prioritise their limited resources, there is a tendency for 'waiting lists' for non-crucial treatment in countries with such systems, as opposed to letting higher-payers get treated first, so sometimes those who can afford it take out private health care to get treatment more quickly.[60] On the other hand, some countries, including the USA, have in the twentieth century introduced a private-based, for-profit-approach to providing hospital care, with few state-money supported 'charity' hospitals remaining today.[61] Where for-profit hospitals in such countries admit uninsured patients in emergency situations (such as during and after Hurricane Katrina in the USA), they incur direct financial losses,[61] ensuring that there is a clear disincentive to admit such patients. In the United States, laws exist to ensure patients receive care in life-threatening emergency situations regardless of the patient's ability to pay.[62]

As the quality of health care has increasingly become an issue around the world, hospitals have increasingly had to pay serious attention to this matter. Independent external assessment of quality is one of the most powerful ways to assess this aspect of health care, and hospital accreditation is one means by which this is achieved. In many parts of the world such accreditation is sourced from other countries, a phenomenon known as international healthcare accreditation, by groups such as Accreditation Canada from Canada, the Joint Commission from the USA, the Trent Accreditation Scheme from Great Britain, and Haute Authorité de santé (HAS) from France.

Buildings

Architecture

Modern hospital buildings are designed to minimise the effort of medical personnel and the possibility of contamination while maximising the efficiency of the whole system. Travel time for personnel within the hospital and the transportation of patients between units is facilitated and minimised. The building also should be built to accommodate heavy departments such as radiology and operating rooms while space for special wiring, plumbing, and waste disposal must be allowed for in the design.[63]

However, many hospitals, even those considered "modern", are the product of continual and often badly managed growth over decades or even centuries, with utilitarian new sections added on as needs and finances dictate. As a result, Dutch architectural historian Cor Wagenaar has called many hospitals:

- "... built catastrophes, anonymous institutional complexes run by vast bureaucracies, and totally unfit for the purpose they have been designed for ... They are hardly ever functional, and instead of making patients feel at home, they produce stress and anxiety."[64]

Some newer hospitals now try to re-establish design that takes the patient's psychological needs into account, such as providing more fresh air, better views and more pleasant colour schemes. These ideas harken back to the late eighteenth century, when the concept of providing fresh air and access to the 'healing powers of nature' were first employed by hospital architects in improving their buildings.[64]

The research of British Medical Association is showing that good hospital design can reduce patient's recovery time. Exposure to daylight is effective in reducing depression. Single-sex accommodation help ensure that patients are treated in privacy and with dignity. Exposure to nature and hospital gardens is also important – looking out windows improves patients' moods and reduces blood pressure and stress level. Open windows in patient rooms have also demonstrated some evidence of beneficial outcomes by improving airflow and increased microbial diversity.[65][66] Eliminating long corridors can reduce nurses' fatigue and stress.[67]

Another ongoing major development is the change from a ward-based system (where patients are accommodated in communal rooms, separated by movable partitions) to one in which they are accommodated in individual rooms. The ward-based system has been described as very efficient, especially for the medical staff, but is considered to be more stressful for patients and detrimental to their privacy. A major constraint on providing all patients with their own rooms is however found in the higher cost of building and operating such a hospital; this causes some hospitals to charge for private rooms.[68]

See also

References

- ↑ "Hospitals". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- 1 2 3 "India's 'production line' heart hospital". bbcnews.com. 1 August 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ↑ Hall, Daniel (December 2008). "Altar and Table: A phenomenology of the surgeon-priest". Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 81 (4): 193–8. PMC 2605310. PMID 19099050.

Although physicians were available in varying capacities in ancient Rome and Athens, the institution of a hospital dedicated to the care of the sick was a distinctly Christian innovation rooted in the monastic virtue and practise of hospitality. Arranged around the monastery were concentric rings of buildings in which the life and work of the monastic community was ordered. The outer ring of buildings served as a hostel in which travellers were received and boarded. The inner ring served as a place where the monastic community could care for the sick, the poor and the infirm. Monks were frequently familiar with the medicine available at that time, growing medicinal plants on the monastery grounds and applying remedies as indicated. As such, many of the practicing physicians of the Middle Ages were also clergy.

- ↑ Lovoll, Odd (1998). A Portrait of Norwegian Americans Today. U of Minnesota Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-8166-2832-2.

- ↑ Cassell's Latin Dictionary, revised by J. Marchant & J. Charles, 260th. thousand.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Our Background". District Hospital Leadership Forum. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Knox, Dennis. "District Hospitals' Important Mission". Payers &–° Providers. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Narayana Hrudayalaya Hospitals". fastcompany.com. 7 February 2012. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ↑ Risse, G.B. Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals. 1990. p. 56

- ↑ Risse, G.B. Mending bodies, saving souls: a history of hospitals. Oxford University Press, 1990. p. 56 Books.Google.com

- ↑ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopaedia of Medical History (Macmillan 1985), pp.134–5.

- ↑ Legge, James (1965). A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fâ-Hien of his Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399–414) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline.

- 1 2 The Nurses should be able to Sing and Play Instruments – Wujastyk, Dominik; University College London. Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Prof. Arjuna Aluvihare, "Rohal Kramaya Lovata Dhayadha Kale Sri Lankikayo" Vidhusara Science Magazine, November 1993.

- ↑ Resource Mobilisation in Sri Lanka's Health Sector – Rannan-Eliya, Ravi P. & De Mel, Nishan, Harvard School of Public Health & Health Policy Programme, Institute of Policy Studies, February 1997, Page 19. Accessed 22 February 2008.

- ↑ Heinz E Müller-Dietz, Historia Hospitalium (1975).

- ↑ Ayurveda Hospitals in ancient Sri Lanka Archived 7 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine. – Siriweera, W. I., Summary of guest lecture, Sixth International Medical Congress, Peradeniya Medical School Alumni Association and the Faculty of Medicine

- ↑ The Roman military Valetudinaria: fact or fiction – Baker, Patricia Anne, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Sunday 20 December 1998

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia – (2009) Accessed April 2011.

- ↑ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopedia of Medical History (Macmillan 1985), p.135.

- ↑ James Edward McClellan and Harold Dorn, Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), p.99,101.

- ↑ Byzantine medicine

- ↑ The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 22:2 Mehmet Mahfuz Söylemez, The Gundeshapur School: Its History, Structure, and Functions, p.3.

- ↑ Gail Marlow Taylor, The Physicians of Gundeshapur, (University of California, Irvine), p.7.

- ↑ Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p.7.

- ↑ Cyril Elgood, A Medical History of Persia and the Eastern Caliphate, (Cambridge University Press, 1951), p.3.

- ↑ Husain F. Nagamia, [Islamic Medicine History and Current practise], (2003), p.24.

- ↑ Sir Glubb, John Bagot (1969), A Short History of the Arab Peoples, retrieved 25 January 2008

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Islamic Roots of the Modern Hospital". aramcoworld.com. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ Guenter B. Risse, Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals, (Oxford University Press, 1999), p.125

- ↑ The Hospital in Islam, [Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic Science, An Illustrated Study], (World of Islam Festival Pub. Co., 1976), p.154.

- 1 2 Islamic Culture and the Medical Arts: Hospitals, United States National Library of Medicine

- ↑ "The Islamic roots of modern pharmacy". aramcoworld.com. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Rise and spread of Islam. Gale. 2002. p. 419. ISBN 9780787645038.

- ↑ Medicine And Health, "Rise and Spread of Islam 622–1500: Science, Technology, Health", World Eras, Thomson Gale.

- ↑ Alatas, Syed Farid (2006). "From Jami'ah to University: Multiculturalism and Christian–Muslim Dialogue". Current Sociology. 54 (1): 112–32. doi:10.1177/0011392106058837.

- ↑ "Pioneer Muslim Physicians". aramcoworld.com. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ Philip Adler; Randall Pouwels (2007). World Civilizations. Cengage Learning. p. 198. ISBN 9781111810566. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ↑ Bedi N. Şehsuvaroǧlu (2012-04-24). "Bīmāristān". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; et al. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition (2nd ed.). Retrieved 5 June 2014. More than one of

|encyclopedia=and|journal=specified (help) - ↑ Mohammad Amin Rodini (7 July 2012). "Medical Care in Islamic Tradition During the Middle Ages" (PDF). International Journal of Medicine and Molecular Medicine. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ↑ Gordon, Benjamin, Medieval and Renaissance Medicine, (New York: Philosophical Library, 1959) , 313. Catholic Encyclopedia, ed. Charles Herberman, et al., Vol. VII, “Hospitals”, (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910), 481-2. By 1715, 150 years after the death of St. John of God, over 250 hospitals had been constructed throughout Europe and the New World through the assistance of the Order he founded. See Grace Goldin, Work of Mercy (Ontario: Boston Mills Press, 1994), 33, 50-57.

- ↑ Watson Sethina (2006). "The Origins of the English Hospital". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Sixth Series. 16: 75–94. doi:10.1017/s0080440106000466. JSTOR 25593861.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Orme, Nicholas; Webster, Margaret (1995). The English Hospital. Yale University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-300-06058-4.

- 1 2 Bowers, Barbara S. (2007). The Medieval Hospital and Medical Practice. Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-7546-5110-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Abreu, Laurinda (2013). Hospital Life : Theory and Practice from the Medieval to the Modern. Pieterlen Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. pp. 21–34. ISBN 978-3-0353-0517-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Rawcliffe, Carole (1999). Medicine for the Soul: The Life, Death and Resurrection of an English Medieval Hospital- St. Giles's Norwich, c. 1249–1550. Sutton Publishing. p. xvi. ISBN 978-0-7509-2009-4.

- 1 2 3 Clay, Rotha Mary (1909). The Medieval Hospitals of England. London: Methuen & Co. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-7905-4209-6.

- ↑ Reinarz, Jonathan (2007). "Corpus Curricula: Medical Education and the Voluntary Hospital Movement". Brain, Mind and Medicine: Essays in Eighteenth-Century Neuroscience. pp. 43–52. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-70967-3_4. ISBN 978-0-387-70966-6.

- ↑ Roderick E. McGrew, Encyclopedia of Medical History (Macmillan 1985), p.139.

- ↑ Michael Marks Davis; Andrew Robert Warner (1918). Dispensaries, Their Management and Development: A Book for Administrators, Public Health Workers, and All Interested in Better Medical Service for the People. MacMillan. pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Surgeon Vice Admiral A Revell in http://www.histansoc.org.uk/uploads/9/5/5/2/9552670/volume_19.pdf

- ↑ Waddington Ivan (1975). "The Development of Medical Ethics - A Sociological Analysis". Medical History. 19 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1017/s002572730001992x. PMC 1081608. PMID 1095851.

- ↑ Porter, Roy (1999) [1997]. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 316–317. ISBN 978-0-393-31980-4.

- ↑ Kathy Neeb (2006). Fundamentals of Mental Health Nursing. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. ISBN 9780803620346.

- ↑ Nightingale, Florence (August 1999). Florence Nightingale: Measuring Hospital Care Outcomes. ISBN 978-0-86688-559-1. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ↑ Erna Lesky, The Vienna Medical School of the 19th Century (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976)

- 1 2 Emanuel, Ezekiel J. (2018-02-25). "Opinion | Are Hospitals Becoming Obsolete?". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, 2018 | AHA".

- ↑ https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/hai/infections_deaths.pdf

- ↑ Johnston, Martin (21 January 2008). "Surgery worries create insurance boom". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- 1 2 Hospitals in New Orleans see surge in uninsured patients but not public funds – USA Today, Wednesday 26 April 2006

- ↑ "Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA)". centres for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2012-03-26. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ↑ Annmarie Adams, Medicine by Design: The Architect and the Modern Hospital, 1893–1943 (2009)

- 1 2 Healing by design Archived 17 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. – Ode Magazine, July/August 2006 issue. Accessed 10 February 2008.

- ↑ Sample, Ian (2012-02-20). "Open hospital windows to stem spread of infections, says microbiologist". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ↑ Bowdler, Neil (2013-04-26). "Closed windows 'increase infection'". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- ↑ "The psychological and social needs of patients". British Medical Association. 7 January 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ↑ Health administrators go shopping for new hospital designs Archived 26 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. – National Review of Medicine, Monday 15 November 2004, Volume 1 NO. 21

Bibliography

History of hospitals

- Brockliss, Lawrence, and Colin Jones. "The Hospital in the Enlightenment," in The Medical World of Early Modern France (Oxford UP, 1997), pp. 671–729; covers France 1650–1800

- Chaney, Edward (2000),"'Philanthropy in Italy': English Observations on Italian Hospitals 1545–1789", in: The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance, 2nd ed. London, Routledge, 2000. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_evolution_of_the_grand_tour.html?id=rYB_HYPsa8gC

- Connor, J. T. H. "Hospital History in Canada and the United States," Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 1990, Vol. 7 Issue 1, pp 93–104

- Crawford, D.S. Bibliography of Histories of Canadian hospitals and schools of nursing.

- Gorsky, Martin. "The British National Health Service 1948–2008: A Review of the Historiography," Social History of Medicine, December 2008, Vol. 21 Issue 3, pp 437–460

- Harrison, Mar, et al. eds. From Western Medicine to Global Medicine: The Hospital Beyond the West (2008)

- Horden, Peregrine. Hospitals and Healing From Antiquity to the Later Middle Ages (2008)

- McGrew, Roderick E. Encyclopedia of Medical History (1985)

- Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (1996), Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, 3, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2

- Porter, Roy. The Hospital in History, with Lindsay Patricia Granshaw (1989) ISBN 978-0-415-00375-9

- Risse, Guenter B. Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals (1999); world coverage

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America's Hospital System (1995); history to 1920

- Scheutz, Martin et al. eds. Hospitals and Institutional Care in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (2009)

- Wall, Barbra Mann. American Catholic Hospitals: A Century of Changing Markets and Missions (Rutgers University Press, 2011). ISBN 978-0-8135-4940-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hospital. |

- Database

- "Global and Multilanguage Database of public and private hospitals". hospitalsworldguide.com.

- "Directory and Ranking of more than 17.000 Hospitals worldwide". hospitals.webometrics.info.

- "Medical History". open access scholarly journal.