2010s Haiti cholera outbreak

| Date | October 2010 – present |

|---|---|

| Location | Haiti |

| Cause | Suspected contamination by United Nations peacekeepers.[1][2] |

| Casualties | |

| 10,075 dead (all countries) | |

|

Cases: Cases recorded in: | |

The 2010-2017 Haitian cholera outbreak was the first modern large scale outbreak of cholera, once considered a beaten back disease thanks to the invention of modern sanitation, yet now resurgent, having spread across Haiti from October 2010 to May 2017, waxing and waning with eradication effort and climate variability. Early efforts were made to cover up the source of the epidemic, but thanks largely to the investigations of journalist Jonathan M. Katz and epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux,[5] today it is believed widely to be the result of contamination by infected United Nations peacekeepers deployed from Nepal.[6] In terms of total infections, the outbreak has since been surpassed by the war-fueled 2016–17 Yemen cholera outbreak, although the Haiti outbreak is still the most deadly modern outbreak.[7]

Summary of size and development

The outbreak began in mid October 2010 in the rural Center department of Haiti,[8] about 100 kilometres (62 mi) north of the capital, Port-au-Prince. By the first 10 weeks of the epidemic, cholera spread to all of Haiti's 10 departments or provinces.[9] It had killed 4,672 people by March 2011[10] and hospitalized thousands more.[11]

As of 12 December 2012, hospitalizations (2,300 per week) and deaths (40 per week) had roughly tripled since Hurricane Sandy struck the island in what was expected to be a quiet cholera season. Cholera caused more deaths than all deaths related to the hurricane.[3] In November 2010, the first cases of cholera were reported in the Dominican Republic and a single case in Florida, United States; in January 2011, a few cases were reported in Venezuela. The epidemic came back strongly in the 2012 rainy season, despite a localised delayed vaccine drive. In late June 2012, Cuba confirmed three deaths and 53 cases of cholera in Manzanillo,[12] in 2013 with 51 cases in Havana.[13] Vaccination of half the population was urged by the University of Florida to stem the epidemic.[14][15]

By March 2017, it had killed 9,985 Haitians and others and sickened several hundred thousand persons while spreading to the neighboring countries of the Dominican Republic and Cuba.[16] When the outbreak began in October 2010, more than 6% of Haitians resulted in acquiring the disease.[17] While there had been an apparent lull in cases in 2014, by August 2015 the rainy season brought a spike in the number of cases. At that time more than 700,000 Haitians had become ill with the disease and the death toll had climbed to 9,000.[18]

Background

.jpg)

Before the outbreak, Haiti suffered from relatively poor public health and sanitation infrastructure. As of 2008, 37% of Haiti's population lacked access to adequate drinking water, and 83% lacked improved sanitation facilities.[19] This made Haiti particularly vulnerable to an outbreak of waterborne disease. In January, 2010, a massive earthquake hit Haiti, killing over 100,000 people and further disrupting healthcare and sanitation infrastructure in the country.[20][21] In the aftermath of the earthquake, international workers from many countries arrived in Haiti to assist in the rebuilding effort, including a number of workers from countries where cholera was endemic. This presented an opportunity for cholera to spread to Haiti.[22] Furthermore, Haiti had likely never suffered an outbreak of cholera previously; as such the population of Haiti had little to no immunity to cholera.[23]

Outbreak

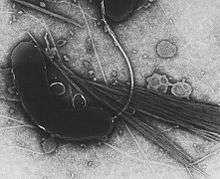

The suspected source for the epidemic was the Artibonite River, from which most of the affected people had drunk water.[11] The outbreak occurred ten months after a powerful earthquake which devastated the nation's capital and southern towns on 12 January 2010, leading some observers to wrongly suspect it was a result of the disaster.[24][25] But immediate suspicion among Haitians centered on a UN military base on a tributary of that river home to peacekeepers from Nepal.[26] MINUSTAH officials issued a press statement denying the possibility that the base could have caused the epidemic, citing stringent sanitation standards.[27]

The next day, 27 October, Katz, an Associated Press correspondent, visited the base and found gross inconsistencies between the statement and the base's actual conditions. Katz also happened upon UN military police taking samples of ground water to test for cholera, despite UN assertions that it was not concerned about a possible link between its soldiers and the disease. Neighbors told the reporter that waste from the base often spilled into the river.[28] Later that day, a crew from Al Jazeera English including reporter Sebastian Walker filmed the soldiers trying to excavate a leaking pipe; the video was posted online the next day and, citing AP's report, drew increased awareness to the base.[29] MINUSTAH spokesmen later contended that the samples taken from the base proved negative for cholera. However, an AP investigation showed that the tests were improperly done at a laboratory in the Dominican Republic with no experience of testing for cholera.[30]

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said its tests of "DNA fingerprinting" showed various samples of cholera from Haitian patients were identified as Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1, serotype Ogawa, a strain found in South Asia.[31][32]

For three months, UN officials, the CDC, and others argued against investigating the source of the outbreak. Gregory Hartl, a spokesman for the World Health Organization (WHO), said finding the cause of the outbreak was "not important". "Right now, there is no active investigation. I cannot say one way or another [if there will be]. It is not something we are thinking about at the moment. What we are thinking about is the public health response in Haiti."[33] Jordan Tappero, the lead epidemiologist at the CDC, said the main task was to control the outbreak, not to look for the source of the bacteria and that "we may never know the actual origin of this cholera strain."[34] A CDC spokesperson, Kathryn Harben, added that "at some point in the future, when many different analyses of the strain are complete, it may be possible to identify the origin of the strain causing the outbreak in Haiti."

Paul Farmer, co-founder of the medical organisation Partners In Health and a UN official himself who served Bill Clinton's deputy at the Office of the Special Envoy for Haiti, told the AP's Katz on 3 November that there was no reason to wait. "The idea that we'd never know is not very likely. There's got to be a way to know the truth without pointing fingers." A cholera expert, John Mekalanos, supported the assertion that it was important to know where and how the disease emerged because the strain is a "novel, virulent strain previously unknown in the Western Hemisphere and health officials need to know how it spreads." The Swedish ambassador to Haiti said the epidemic had strains originating in Nepal.[35] However, Nepal's representative to the United Nations "categorically refuted" the hypothesis that Nepali peacekeepers were the source of the outbreak.[36]

Under intense pressure, the UN relented, and said it would appoint a panel to investigate the source of the cholera strain.[37] That panel's report, issued in May 2011, confirmed substantial evidence that the Nepalese troops had brought the disease to Haiti. However, in the report's concluding remarks, the authors hedged to say that a "confluence of circumstances" was to blame.[8]

Some US professors have disagreed with the contention that Nepalese soldiers caused the outbreak. Some said it was more likely dormant cholera bacteria had been aroused by various environmental incidents in Haiti.[38] Before studying the case, they said a sequence of events, including changes in climate triggered by the La Niña climate pattern and unsanitary living conditions for those affected by the earthquake, triggered bacteria already present to multiply and infect humans.[38]

However, a study unveiled in December and conducted by French epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux contended that UN troops from Nepal had started the epidemic as waste from outhouses at their base flowed into and contaminated the Artibonite River.[39] A separate study published in December in the New England Journal of Medicine presented DNA sequence data for the Haitian cholera isolate, finding that it was most closely related to a cholera strain found in Bangladesh in 2002 and 2008. It was more distantly related to existing South American strains of cholera, the authors reported, adding that "the Haitian epidemic is probably the result of the introduction, through human activity, of a V. cholerae strain from a distant geographic source."[40] Rita Colwell, former director of the National Science Foundation and climate change expert, still contends that climate changes were an important factor in cholera's spread, stating in an interview with UNEARTH News in August 2013 that the outbreak was "triggered by a complicated set of factors. The precipitation and temperatures were above average during 2010 and that, in conjunction with a destroyed water and sanitation infrastructure, can be considered to have contributed to this major disease outbreak."[41]

In August 2016, after Katz obtained a leaked copy of a report by United Nations Special Rapporteur Philip Alston,[42][42] Secretary General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon accepted responsibility for the UN's role in the initial outbreak and stated that a "significant new set of U.N. actions" will be required to help solve the problem.[2]

International spread

Cholera was reported in the Dominican Republic in mid-November 2010,[43] following the Pan-America Health Organisation's prediction.[44] By January 2011, the Dominican Republic had reported 244 cases of cholera.[45] The first man to die of it there died in the province of Altagracia on 23 January 2011.[45][46]

On 15 November the director of programming for Catholic Relief Services in Haiti, said, "Some people have been reporting that we've gotten in front of it and are in control of the spread of cholera. Actually WHO does not believe that. There's such a severe underreporting of cases that they're not sure of all of the hot spots."[9][47]

In late January 2011, more than 20 Venezuelans were reported to have been taken to hospital after contracting cholera after visiting the Dominican Republic.[48][49] 37 cases were reported in total.[45] Contaminated food was blamed for the spread of the disease.[50] Venezuelan health minister Eugenia Sader gave a news conference which was broadcast on VTV during which she described all 37 people as "doing well".[45] The minister had previously observed that the last time cholera was recorded in Venezuela was twenty years before this, in 1991.[45]

On 15 March 2011, a report was issued by the University of California that predicted total infections would number up to 779,000 and total deaths up to 11,000 by November 2011, compared with earlier UN estimates that around 400,000 people would end up infected.[51] The revised numbers were based on more factors than the UN's estimates, which assumed a total infection rate of between two and four percent of the population.[51] In a statement released at the same time, the WHO said total deaths thus far had reached 4,672, with 252,640 cases reported.[51]

Within the time period of October 2010 to October 2014, a total of 711,442 confirmed cases of cholera occurred.[52] Of these cases 400,103 were hospitalized and 8,646 died, resulting in a cumulative case-fatality rate of 1.2%.[52] Variations in case-fatality rates were observed based on location.[52] The case fatality rate in the department of Sud-Est was 4.4%, compared to 0.6% in Port-au-Prince.[52]

Domestic reactions

There were fears that following the discovery of 15 cases in the capital, the epidemic could spread further.[53] On 15 November, a riot broke out in Cap-Haïtien following the death of a young Haitian inside the Cap-Haïtien UN base and rumours that the outbreak was caused by UN soldiers from Nepal.[54] Protesters demanded that the Nepalese brigade of the UN leave the country.[55] At least 5 people were killed in the riots, including 1 UN personnel.[56] Riots then continued for a second day.[57]

Following the riots the UN said the outbreak was being staged for "political reasons because of forthcoming elections", as the Haitian government sent its own forces to "protest" the UN peacekeepers.[58] During a third day of riots UN personnel were blamed for shooting at least 5 protestors but denied responsibility.[59] On the fourth day of demonstrations against the UN presence, police fired tear gas into an IDP camp in the capital.[60] Riots following the election were a cause for concern in the ability to contain the epidemic.[61]

Casualties over the years

Even before the outbreak Haiti has suffered from infectious diseases due to crowded living conditions and lack of clean water and sewage disposal. There is also a chronic shortage of health care personnel, and hospitals lack resources, a situation that became readily apparent after the January 2010 earthquake.[62]

Some aid agencies have reported that the toll may be higher than the official figures because the government does not track deaths in rural areas where people never reached a hospital or emergency treatment center.[47] In 2011, reports suggested over 6,700 people had been killed during the outbreak.[63]

By March 2011, after the initial intense flare up, some 4,672 people died and as of March 2012, cholera has killed more than 7,050 Haitians and sickened more than 531,000, or 5 percent of the population.[51][64]

The next years there was significant progress reduction of caseloads and deaths, with solid backing of international medical efforts and preventative measures, including latrines installed and changes in Haitian behaviors, such as thoroughly cooking food and rigorous handwashing. However, roughly 75% of Haitian households lack running water and thousands still live in camps or similar substandard conditions. Despite all these efforts, every rainy season or hurricane has caused a temporary spike in cases and deaths. Per the Haitian Health Ministry, as of August 2012, the outbreak had caused 7,490 deaths and caused 586,625 people to fall ill.[65] According to the Pan American Health Organization, as of 21 November 2013, there had been 689,448 cholera cases in Haiti, leading to 8,448 deaths.[66]

In the first 4 months of 2016, there were nearly 14,000 new cases of cholera and over 150 deaths.[67] Six years after the outbreak, the disease is still killing an average of 37 people a month.[68] As of March 2017, around 7% of Haiti's population (around 800,665 people) have been affected with cholera, and 9,480 Haitians have died.

Political reactions

On 12 November 2010, the United Nations issued an appeal for around US$160 million to fight the spread of the disease, saying that "all our efforts can be outrun by the epidemic" and warned of a lack of space for patients in hospitals.[69] It also denied that the Nepali contingent were responsible for the outbreak.[56] In November 2011, the UN received a petition from 5,000 victims for hundreds of millions of dollars in reparations over the outbreak thought to have been caused by UN members of MINUSTAH.[63] In February 2013, the United Nations responded by invoking its immunity from lawsuits under the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations.[70] On 9 October 2013, Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI), the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), and civil rights lawyer Ira Kurzban's law firm Kurzban Kurzban Weinger Tetzeli & Pratt, P.A.(KKWT) filed a lawsuit against the UN in the Southern District of New York.[71] The lawsuit was dismissed, but an appeal was filed in the Second Circuit.[72] In October 2016, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the United Nations' immunity from claims.[73] In December 2016, the then UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon finally apologized on behalf of UN, saying he was "profoundly sorry" for the outbreak.[74] The Secretary-General promised to spend $400 million to aid the victims and to improve the nation's crumbling sanitation and water systems. As of March 2017, the UN has come through with only 2 percent of that amount.[75]

The outbreak of cholera became an issue for candidates to answer in the 2010 general election.[76] There were fears that the election could be postponed. The head of MINUSTAH, Edmond Mulet said that it should not be delayed as that could lead to a political vacuum with untold potential problems.[77]

See also

Further reading

- Frerichs, Ralph R. Deadly River: Cholera and Cover-Up in Post-Earthquake Haiti. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2016. 978-1-5017-0230-3

- Katz, Jonathan M. The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. ISBN 978-0230341876

- Wilentz, Amy Farewell, Fred Voodoo: A Letter from Haiti. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013. ISBN 978-1451643978

References

- ↑ "U.N. Admits Role in Cholera Epidemic in Haiti". New York Times. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- 1 2 Jonathan M. Katz (17 August 2016). "U.N. Admits Role in Cholera Epidemic in Haiti". New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Epidemiological Update Cholera 28 Dec 2017".

- 1 2 "Epidemiological Update Cholera 19 October 2013". WHO. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ Freichs, Ralph R. Deadly River. ISBN 1501702300.

- ↑ Katz, Jonathan M. (2016-08-19). "The U.N.'s Cholera Admission and What Comes Next". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ↑ "News Scan for Dec 21, 2017". umn.edu. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- 1 2 "Final Report of the Independent Panel of Experts on the Cholera Outbreak in Haiti" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- 1 2 Basu, Moni (31 December 2010). "Cholera death toll in Haiti rises to more than 3,000". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ↑ "PAHO's Interactive Atlas of Cholera in la Hispaniola". new.paho.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- 1 2 "Cholera cases found in Haiti capital". MSNBC. 23 October 2010. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ Sarah Rainsford (3 July 2012). "Cuba confirms deadly cholera outbreak". BBC. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ↑ "Cuba confirms 51 cholera cases in Havana". BBC News. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ "To stop cholera in Haiti, vaccinate some—not all". Futurity. 11 January 2013. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ "Vaccinating Half of Haiti's Population Could Stem Cholera Epidemic: Report". Caribbean Journal. 17 January 2013. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ Government of Haiti, health ministry "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Roos, Robert (9 January 2013). "Cholera has struck more than 6% of Haitians". CIDRAP. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013.

- ↑ Editorial board (12 August 2015). "UN must step up, apologize, and help drive cholera from Haiti". The Boston Globe newspaper. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ World Health Organization; United Nation Children's Fund (2010). "Progress on sanitation and drinking water: Joint Monitoring Programme 2010 update". p. 43. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Maura R. O'Connor (12 January 2012). "Two years later, Haitian earthquake death toll in dispute". Columbia Journalism Review. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Dowell SF, Tappero JW, Frieden TR (27 January 2011). "Public Health in Haiti — Challenges and Progress". New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (4): 300–301. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1100118.

- ↑ Somini Sengupta (1 December 2016). "U.N. apologizes for role in Haiti's 2010 cholera outbreak". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ↑ Jenson D; Szabo V; Duke FHI Haiti Humanities Laboratory Student Research Team (November 2011). "Cholera in Haiti and Other Caribbean Regions, 19th Century". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (11). doi:10.3201/eid1711.110958. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ↑ "In the Time of Cholera". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ↑ Katz, Jonathan (2014). The Big Truck That Went By. St Martins Press. pp. 219–222. ISBN 1137278978.

- ↑ "UPDATE: Community Outcry Blaming Nepalese MINUSTAH Deployment in Mirebalais". 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013.

- ↑ "MINUSTAH denies rumour that it spread cholera in Haiti". 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "UN probes base as source of Haiti cholera outbreak". 27 October 2010. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ Al Jazeera English 28 October 2010 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ "UN worries its troops caused cholera in Haiti". 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 6 January 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ "Haiti cholera 'resembles South Asian strain'". BBC News. 1 November 2010. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ "CDC Announces Laboratory Test Results of Cholera Outbreak Strain in Haiti". Infection Control Today. Archived from the original on 2 November 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ Katz, Jonathan M.; Associated Press (3 November 2010). "Experts ask: Did U.N. troops infect Haiti?". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 7 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ "Haiti's cholera 'from South Asia'". Al Jazeera English. 2 November 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ "Svenska ambassadören: "Smittan kommer från Nepal" (Swedish)". Svenska Dagbladet. 16 November 2010. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- ↑ "Nepal's UN Mission Denies Blame For Haiti Outbreak".

- ↑ "UN panel to investigate Haiti cholera outbreak". Associated Press. 17 December 2010. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- 1 2 "Haiti's cholera epidemic caused by weather, say scientists". The Guardian. UK. 22 November 2010. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ↑ "Haiti cholera: UN peacekeepers to blame, report says". BBC News. 7 December 2010. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ↑ Chin, C. S.; Sorenson, J.; Harris, J. B.; Robins, W. P.; Charles, R. C.; Jean-Charles, R. R.; Bullard, J.; Webster, D. R.; Kasarskis, A.; Peluso, P.; Paxinos, E. E.; Yamaichi, Y.; Calderwood, S. B.; Mekalanos, J. J.; Schadt, E. E.; Waldor, M. K. (2011). "The Origin of the Haitian Cholera Outbreak Strain". New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1012928. PMC 3030187. PMID 21142692.

- ↑ Auber, T. (7 August 2013). "UN peacekeepers or climate change? The complex factors contributing to Haiti's cholera crisis". UNEARTH News. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Philip Alston's Draft Report on the U.N. and the Haiti Cholera Outbreak". 19 August 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ "Haiti cholera reaches Dominican Republic". BBC News. 16 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ↑ "Cholera death toll in Haiti passes 600". BBC News. 10 November 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Venezuela reports 37 cholera cases". CNN. 27 January 2011. Archived from the original on 30 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ↑ "Case of Cholera in Florida Is Linked to Haiti Outbreak". The New York Times. 17 November 2010. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Haiti cholera toll rises as medical supplies are rushed to victims". US Catholic. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ "Cholera alert reaches Venezuela via Dominican Republic". BBC News. 26 January 2011. Archived from the original on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ↑ "Cholera Arrives in Venezuela". Latin American Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012.

- ↑ Ezequiel Minaya (27 January 2011). "Venezuela's Confirmed Cholera Cases Increases To Nearly 40". The Wall Street Journal. News Corporation. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Haiti cholera 'far worse than expected', experts fear". BBC News. 15 March 2011. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Epidemiological Update: Cholera". Pan American Health Organization. 6 November 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Cholera spreads to Haitian capital". Al Jazeera English. 9 November 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ↑ "Cholera protesters barricade Haiti city, assail UN". Associated Press. 15 November 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- ↑ "UN troops blamed for Haiti cholera". Al Jazeera English. 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- 1 2 "Haiti cholera protest turns violent – Americas". Al Jazeera English. 29 September 2010. Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ "UN faces heat over Haiti cholera". Al Jazeera. 17 November 2010. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ↑ "Haiti riots against UN heat up". Al Jazeera. 17 November 2010. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ↑ "UN blamed for Haiti shootings". Al Jazeera. 17 November 2010. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ↑ "Cholera unrest hits Haiti capital". Al Jazeera. 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ↑ "Haiti vote chaos continues". Al Jazeera. 29 November 2010. Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ↑ Robert Lee Hadden and Steven G. Minson. 2010. The Geology of Haiti: An Annotated Bibliography of Haiti's Geology, Geography and Earth Science. handle.dtic.mil. p. 10.

- 1 2 "UN hit with cash demand over Haiti cholera - Americas". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ↑ Deborah Sontag (31 March 2012). "In Haiti, Global Failures on a Cholera Epidemic". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ↑ Megan Dhaliwal (7 August 2012). "Panic Has Subsided, But Cholera Remains in Haiti". Pulitzer Center. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ Pan American Health Organization (21 November 2013). "Epidemiological Update, Cholera". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ "Breaking News, World News & Video from Al Jazeera". video.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ "Cholera quietly still kills dozens a month in Haiti". ap.org. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ "Haiti cholera toll tops 900 with six provinces affected". Reuters. 14 November 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ↑ Pilkington, Ed (21 February 2013). "UN will not compensate Haiti cholera victims, Ban Ki-moon tells president". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti: Cholera Litigation". www.ijdh.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ "BAI/IJDH and Cholera Victims Appeal Court's Dismissal of Their Case". IJDH. Archived from the original on 20 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ↑ Moloney, Anastasia. "U.S. judge upholds U.N. immunity in Haiti cholera case". reuters.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ Sengupta, Somini (1 December 2016). "U.N. Apologizes for Role in Haiti's 2010 Cholera Outbreak". Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ "Haiti is still waiting on promised UN help for cholera epidemic". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ "Haiti: Seismic Election". Al Jazeera. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 18 November 2010.

- ↑ "Unrest 'must not stop Haiti polls'". Al Jazeera. 20 November 2010. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

External links

| Wikinews has news related to: |

- Centers for Disease Control page on the outbreak

- PAHO Situation Reports on the Haiti cholera outbreak

- Cholera Will Not Go Away Until Underlying Situations that Make People Vulnerable Change – video report by Democracy Now!

- Not Doing Enough: Unnecessary Sickness and Death from Cholera in Haiti, from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, August 2011

- Responding to the Cholera Emergency, in Best Practices and Lessons Learnt in Communication with Disaster Affected Communities, a infoasaid report, November 2011

- Rebuilding in Haiti Lags After Billions in Post-Quake Aid: Lofty Hopes and Hard Truths, New York Times Dec 2012

- Institute for Justice and Democracy in Haiti's cholera case with UN