2016–18 Yemen cholera outbreak

.svg.png) | |

| Disease | Cholera |

|---|---|

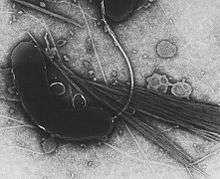

| Bacteria strain | Vibrio cholerae |

| Dates |

October 2016 – present (2 years) |

| Origin |

Yemeni Civil War Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen Saudi Blockade of Yemen Famine in Yemen (2016–present) |

| Deaths | 2,310 from 27 April 2017 to July 1st, 2018[1] |

| Confirmed cases | 612,703[2][3] |

| Suspected cases‡ | 1,055,788 since April 2017 as of February 15th 2018[4] |

| ‡ Suspected cases have not been confirmed as being due to this strain by laboratory tests, although some other strains may have been ruled out. | |

In October 2016, an outbreak of cholera began in Yemen[5] and is ongoing as of October 2018.[6] In February and March 2017, the outbreak was in decline,[7][8] but the number of cholera cases resurged after 27 April 2017,[9] reportedly ten days after Sana'a's sewer system stopped working.[10] Devastation of Yemeni infrastructure, health, water and sanitation systems and facilities by Saudi-led coalition air strikes led to the spread of cholera.[11][12][13] Saudi-led coalition airstrikes are deliberately targeting water systems in Yemen.[14][15][16] The UN accused the Saudi-led coalition of "complete disregard for human life".[17]

The outbreak is a result of the ongoing war led by the Saudi-led coalition against Houthis in Yemen since March 2015. As stated by in the statement of the UNICEF and WHO executive directors: "This deadly cholera outbreak is the direct consequence of two years of heavy conflict. Collapsing health, water and sanitation systems have cut off 14.5 million people from regular access to clean water and sanitation, increasing the ability of the disease to spread. Rising rates of malnutrition have weakened children's health and made them more vulnerable to disease. An estimated 30,000 dedicated local health workers who play the largest role in ending this outbreak have not been paid their salaries for nearly 10 months."[18] The outbreak is of an "unprecedented scale", according to the World Health Organization (WHO), one of the worst in recorded history.[19]

Outbreak

The cholera outbreak began in early October 2016.[5][8] The World Health Organization (WHO) considers the outbreak to be unusual in its rapid and wide geographical spread.[20] The earliest cases were predominantly in the capital, Sana'a, with some occurring in Aden.[5] By the end of October, cases had been reported in the governorates of Al-Bayda, Aden, Al-Hudaydah, Hajjah, Ibb, Lahij and Taiz[21] and, by late November, also in Al-Dhale'a and Amran.[22] By mid-December, 135 districts of 15 governorates had reported suspected cases, but nearly two-thirds were confined to Aden, Al-Bayda, Al-Hudaydah and Taiz.[23] By mid-January of 2017, 80% of cases were located in 28 districts of Al-Dhale'a, Al-Hudaydah, Hajjah, Lahij and Taiz.[20]

By the end of February 2017, the rate of spread in most areas had reduced,[7] and by mid-March 2017, the outbreak was in decline. A total of 25,827 suspected cases, including 129 deaths, had been reported by 26 April 2017.[8]

The number of cholera cases resurged after 27 April 2017.[9] During May, 74,311 suspected cases, including 605 deaths, were reported.[8] By 24 June 2017, UNICEF and WHO estimated that the total number of cases in the country since the outbreak began in October had exceeded 200,000, with 1,300 deaths, and that 5,000 new cases a day were occurring.[9][24][25] The two agencies stated that it was then "the worst cholera outbreak in the world".[9] Approximately half of the cases, and a quarter of the deaths, were among children.[10]

As of 12 June 2017, the case fatality rate for the outbreak was 0.7%, with higher rates in people over 60 years old (3.2%).[26] The serotype of Vibrio cholerae involved is Ougawa.[26] A total of 268 districts from 20 of the country's 23 governorates had reported cases by 21 June 2017;[27] over half are from the governorates of Amanat Al Asimah (the capital Sana'a), Al Hudeideh, Amran and Hajjah, which are all located in the west of the country.[26]

On 23 June 2017, Saudi Arabia authorized a donation in excess of $66 million, while continuing its airstrikes and military operations in Yemen.[28]

By 4 July 2017, there were 269,608 cases and the death toll was at 1,614 with a total case fatality rate of 0.6%.[29]

From 27 April to 14 August there were nearly 2,000 documented death cases from cholera.[30] On 14 August 2017 the WHO updated the number of suspected cholera cases to 500,000.[31]

On 5 September 2017, the World Health Organization updated that number to 612,703 suspected cases, with the death toll standing at 2,048.[32]

On 30 September 2017, the World Health Organization reported 771,945 suspected cases of cholera with 2,132 death cases.[18]

On 22 December 2017, the World Health Organization reported the number of suspected cholera cases in Yemen had surpassed 1 million.[33]

In August 2018, the WHO warned that a third wave of cholera might be underway that was related to Saudi air strikes in the western region around the port city of Hodeidah.[34] By October, WHO was reporting 10,000 suspected cases per week.[35] In May, on oral cholera vaccine campaign was launched,[36] but the shortages of vaccine and the ongoing conflict made delivery into all areas difficult.[37]

Associated factors

UNICEF and WHO attributed the outbreak to malnutrition and collapsing sanitation and clean water systems due to the country's ongoing conflict.[9] An ICRC worker in Yemen noted that April's cholera resurgence began ten days after Sana'a's sewer system stopped working.[10] The impacts of the outbreak have been reported to have been exacerbated by the collapse of the Yemeni health services, where many health workers have remained unpaid for months.[10] The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the UN have pointed to the naval and aerial blockade and bombing campaign by the Saudi-led coalition and the United States Navy as central causes behind the preventable cholera epidemic.[38][39]

With the right medicines, these [diseases] are all completely treatable – but the Saudi Arabia-led coalition is stopping them from getting in.

— Grant Pritchard, Save the Children's interim country director for Yemen, April 2017, Vice News[40]

Efforts to reduce the cholera outbreak

From 27 April 2017 to 20 September 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) has partnered with 50 different organizations across and trained around 900 health workers in Yemen in efforts to combat the cholera crisis. Among the efforts implemented include the opening of 36 diarrhea treatment centers and 139 oral rehydration corners were established. Additionally, medical resources including 1 million bags of IV fluids and 1450 cholera beds have been provided across the country and 158 cholera kits have been distributed. As a result, more than 700,000 people have been treated for suspected cholera. The response has also contributed to a decline in cases in some of the worst-affected districts in the country. More than 99% of the suspected cases are no longer in a life-threatening situation.[41]

News coverage on the cholera outbreak

The cholera outbreak in Yemen has gained global attention and was covered by the media from all over the world. PBS article "Biggest challenge of Yemen’s humanitarian crisis is making the world pay attention" [42] and the Independent's article on "Yemen cholera outbreak set to be the worst on record" [43] are just one of many new coverage that drew attention to the magnitude of the crisis that is happening now in Yemen. Recent headlines highlight that this outbreak is spiraling out of control[44] and could potentially affect more than 1 million lives by 2018.[45][46]

June 2018 - Airstrike on cholera treatment center in Abs

Doctors Without Borders reported that a Saudi Arabian coalition airstrike struck a new Médecins Sans Frontières cholera treatment center in Abs, in northwestern Yemen. Doctors Without Borders reported that they had provided GPS coordinates to Saudi Arabia on twelve separate occasions, and had received nine written responses confirming receipt of those coordinates [47]

See also

References

- ↑ CSR. "WHO EMRO | Outbreak update – Cholera in Yemen, 19 July 2018 | Cholera | Epidemic and pandemic diseases". www.emro.who.int. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ↑ "Epidemiology bulletin 36, 16 July 2017" (PDF). WHO-EMRO. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ "Yemen cholera epidemic slowing after infecting 400,000". Reuters. 25 July 2017.

- ↑ CSR. "WHO EMRO | Outbreak update – cholera in Yemen, 15 February 2018 | Cholera | Epidemic and pandemic diseases". www.emro.who.int. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- 1 2 3 "Cholera cases in Yemen". World Health Organization. 10 October 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "Yemen crisis". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- 1 2 "Update on cholera in Yemen". World Health Organization. 26 February 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Cholera situation in Yemen: May 2017" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Statement from UNICEF Executive Director Anthony Lake and WHO Director-General Margaret Chan on the cholera outbreak in Yemen as suspected cases exceed 200,000". UNICEF. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Bruwer, Johannes (25 June 2017). "The horrors of Yemen's spiralling cholera crisis". BBC News. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "Thousands in Yemen get sick in an entirely preventable cholera outbreak". Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "U.S. Support "Vital" to Saudi Bombing of Yemen, Targeting Food Supplies as Millions Face Famine". Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Kennedy, Jonathan (2 August 2017). "Blame the Saudis for Yemen's cholera outbreak – they are targeting the people - Jonathan Kennedy". the Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "Access to water continues to be jeopardized for millions of children in war-torn Yemen". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "PressTV-UNICEF censures Saudi attacks on Yemen water systems". Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Sputnik. "Water Facility Attack Cuts Off 10,500 People From Safe Drinking Water in Yemen". sputniknews.com. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "Saudi-led air strikes in Yemen killed 68 civilians in one day, UN says". Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- 1 2 "UNICEF Yemen - Media centre - Statement from UNICEF Executive Director Anthony Lake and WHO Director-General Margaret Chan on the cholera outbreak in Yemen as suspected cases exceed 200,000". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ Lyons, Kate (2017-10-12). "Yemen's cholera outbreak now the worst in history as millionth case looms". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- 1 2 "Weekly update: cholera cases in Yemen". World Health Organization. 15 January 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "Update on the cholera situation in Yemen, 30 October 2016". World Health Organization. 30 October 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "Cholera cases in Yemen, 24 November 2016". World Health Organization. 24 November 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "Weekly update: cholera cases in Yemen". World Health Organization. 22 December 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "UN: 1,310 dead in Yemen cholera epidemic". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "Yemen faces world's worst cholera outbreak – UN". BBC News. 25 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Yemen: Cholera outbreak response: Situation report No. 3" (PDF). World Health Organization. 12 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "Weekly update – cholera in Yemen, 22 June 2017". World Health Organization. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ Gladstone, Rick (23 June 2017). "Saudis, at War in Yemen, Give Country $66.7 Million in Cholera Relief". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ↑ "Epidemiology bulletin 26, 4 July 2017" (PDF). WHO-EMRO. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ↑ "Cholera count reaches 500 000 in Yemen". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- ↑ McNeil Jr, Donald G (14 August 2017). "More Than 500,000 Infected With Cholera in Yemen". NY Times. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ "Yemen's cholera epidemic hits 600,000, confounding expectations". Reuters. 2017-09-05. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ↑ "Suspected cholera cases in Yemen surpass one million, reports UN health agency". www.news.un.org. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- ↑ Miles, Tom. "WHO warns of new Yemen cholera surge, asks for ceasefire to vaccinate". U.S. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters. "Yemen cholera outbreak accelerates to 10,000+ cases per week: WHO". U.S. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ publisher, English. "WHO EMRO | Fighting the world's largest cholera outbreak: oral cholera vaccination campaign begins in Yemen | Yemen-news | Yemen". www.emro.who.int. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ "What's really stopping a cholera vaccination campaign in Yemen?". IRIN. 2017-10-17. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- ↑ "'Entirely preventable': Aid agencies blame Yemen blockade, economic collapse for cholera outbreak". RT. 15 May 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "Aid agencies blame Saudi war, blockade for cholera outbreak in Yemen". Press TV. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ Liautaud, Alexa (23 June 2017). "Saudi Arabia donates to end Yemen cholera outbreak it helped start". Vice News. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ Yemen. "WHO EMRO | Situation reports | Yemen-infocus | Yemen". www.emro.who.int. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ "Biggest challenge of Yemen's humanitarian crisis is making the world pay attention". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ "Yemen's man-made cholera crisis is set to become the worst outbreak on record". The Independent. 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (2017-07-13). "'Cholera is everywhere': Yemen epidemic spiralling out of control". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ "Cholera outbreak in Yemen could infect 'unprecedented' 1 million". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ↑ Al Jazeera News. (11 December 2017). "More than 8 million 'a step away' from famine in Yemen". Al Jazeera website Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ↑ "Yemen: Airstrike hits cholera treatment center in Abs". 12 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.