Ghazanchetsots Cathedral

| Ghazanchetsots Cathedral | |

|---|---|

The cathedral in 2014 | |

Shown within Republic of Artsakh | |

| Basic information | |

| Location | 11 Ghazanchetots Street, Shusha (Shushi)[1][lower-alpha 1] |

| Geographic coordinates | 39°45′32″N 46°44′52″E / 39.758819°N 46.747883°ECoordinates: 39°45′32″N 46°44′52″E / 39.758819°N 46.747883°E |

| Affiliation | Armenian Apostolic Church |

| Rite | Armenian |

| Year consecrated |

September 20, 1888 June 18, 1998 (reconsecration) |

| Status | Active |

| Architectural description | |

| Architect(s) | Simon Ter-Hakobian(ts) |

| Architectural style | Armenian |

| Groundbreaking | 1868 |

| Completed | 1887 |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 34.7 metres (114 ft) |

| Width | 23 metres (75 ft) |

| Height (max) | 35 metres (115 ft) |

Holy Savior Cathedral (Armenian: Սուրբ Ամենափրկիչ մայր տաճար, Surb Amenap′rkich mayr tachar), commonly referred to as Ghazanchetsots (Ղազանչեցոց),[lower-alpha 2] is an Armenian Apostolic cathedral in Shusha (Shushi), in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh). It is the seat of the Diocese of Artsakh of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[1][4]

Built between 1868 and 1887, the cathedral was consecrated in 1888. It was damaged during the March 1920 massacre of Armenians of the city by Azerbaijanis and experienced a decades-long decline under Soviet rule. During the Nagorno-Karabakh War Azerbaijan used the cathedral as an armory, where hundreds of missiles were stored. It was restored in the aftermath of the war and reconsecrated in 1998. A landmark of Shusha and Karabakh, it has become an icon for the Karabakh Armenian cause. Standing 35 metres (115 ft) high, Ghazanchetsots is one of the largest Armenian churches in the world.

History

Foundation

According to historical records a small basilica church stood on its place as of 1722.[5] In the 19th century, following the conquest of the Caucasus by the Russian Empire, Shusha was one of the largest cities in region. Thomas de Waal notes that it was larger and more prosperous than either Baku or Yerevan, the current capitals of Azerbaijan and Armenia, respectively.[6] The city was one of the major cities of Armenian cultural activity in the Caucasus, along with Tiflis.[7] According to Russian imperial data of 1886 the city had a mixed Armenian (57%) and Tatar (Azerbaijani) (43%) population of almost 27,000.[8] The earliest part of the current cathedral, the bell tower, was built in 1858, which financed by the Khandamiriants family.[5]

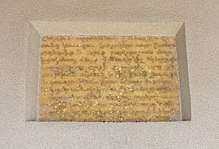

The church's construction began in 1868 and was completed in 1887. Its name comes from Ghazanchi (present-day Qazançı), a village in Nakhichevan, migrants from which financed the church's construction. It was designed by Simon Ter-Hakobian(ts).[5] The church was consecrated on September 20, 1888[9][5] according to an inscription on upper part of the southern portal.[10] The inscription reads:[11]

By the blessing and grace of almighty God this miraculous sacred cathedral is built at the expense and with the donations of the parish of the church of Amenaprkich Ghazanchetsots of the city of Shushi, the construction has commenced in 1868 at the reign of the allpowerful emperor of all Russia Alexander II and the patriarchate of Gevorg IV and was completed in 1887 at the time of the coronation of the son of His Majesty the blessed emperor Alexander III and Catholicos Markar I, on September 20, 1888.

Decline

The majority of the Armenian population of Shusha was massacred or expelled in March 1920. The cathedral was damaged and gradually declined. After the region came under Soviet control, due to the state atheist policies, it was eventually closed down in 1930,[9][4] and was turned into a granary in the 1940s. Its dome and part of the walls surrounding it were destroyed in the 1950s. It was then looted and its stones were used to build several upscale houses in the Azerbaijani part of the city. By the 1970s the cathedral "looked like it survived heavy shelling." Soviet and Azerbaijani authorities granted a permission to launch a restoration project of the cathedral in the 1980s under public pressure.[11] The restoration began in 1981 and continued until 1988 and was supervised by Volodya Babayan.[12][9][4] By 1987 only two of the four stone statues of angels on the bell tower had survived.[13]

Nagorno-Karabakh War

Shusha's Armenian minority was expelled from the city when the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict began in February 1988. The cathedral was turned into an armory by Azerbaijan.[12] According to Armenian political analyst Levon Melik-Shahnazaryan the cathedral was set on fire three times between 1988 and 1991 using car tires.[14] Azerbaijanis dismantled the stone statues of angels on the bell tower in 1989.[15] They reportedly sold off its bronze bell, which was later found in a market in Donetsk, Ukraine and was bought by an Armenian officer for 3 million rubles and sent it back to Armenia.[16] When Shusha was captured by Armenian forces on May 9, 1992, it was a turning point of the war. Prior to the fall of Shusha, Azerbaijani forces stored hundreds of boxes of Grad missiles as the cathedral was safe from potential Armenian bombardment.[17][18][19] Shusha was used as a base for shelling of Stepanakert, the largest city of Karabakh, with Grad launchers for several months.[20][21] Armenian volunteers, including noted activist Igor Muradyan, carried the wooden boxes of artillery and rocket shells out of the church immediately after the capture of the city.[22][23] The flag of Armenia was raised on top of the damaged dome by Armenian troops.[24] Melik-Shahnazaryan wrote that by the time of its capture "practically, only a stone skeleton had remained of the magnificent structure."[14] A foreign visitor noted that its "windows were missing but the interior was in reasonable condition."[23]

On August 23, 1992 Azerbaijani bombers attempted to target the church, however, no serious casualties were reported. Felix Corley suggested that the attempt was not of any military importance and "appeared to be a deliberate attempt to attack the Armenian heritage in Karabakh."[23]

Restoration and revival

Restoration of the church began soon after its capture by Armenian forces. As of 1997 it was reportedly the only building being restored in Shusha.[25] Restoration works were conducted by Volodya Babayan and primarily funded by Andreas Roubian, an Armenian Evangelical benefactor from New Jersey, who provided $110,000. Tens of thousands of dollars came from various Armenian diaspora communities and wealthy individuals.[12][26] Cleanup and furnishing were completed in May 1998.[12] The cathedral was reconsecrated on June 18, 1998 on the Feast of the Transfiguration by Archbishop Pargev Martirosyan, the Primate of the Diocese of Artsakh.[27] The first Divine Liturgy at the restored cathedral took place on July 19 with attendance of Nagorno-Karabakh President Arkadi Ghukasyan and officials from Armenia. Archbishop Sebouh Chouldjian read a letter sent by Catholicos Karekin I,[27] who did not attend due to health problems.[28]

Yulia Antonyan suggested that its reconstruction was "perceived more as a cultural process aimed at a restoration of the Armenian cultural heritage, a spiritual and physical 'rebirth' of the Armenian nation" and came to symbolize the rebirth of Shusha.[29] It now "towers, immaculate once more, above the ruined town," wrote Thomas de Waal in his 2003 book Black Garden.[30] Daniel Bardsley wrote that the cathedral is now "one of the few pristine-looking buildings in the city."[31]

Notable events

On October 16, 2008 a mass wedding, sponsored by Levon Hayrapetyan, a Russian-based businessman from Karabakh, took place in Nagorno-Karabakh. Some 700 couples got married on that day, 500 of whom married at Ghazanchetsots and 200 at Gandzasar monastery.[32][33][34]

.jpg)

On April 14, 2016 Catholicos Karekin II and Catholicos of Cilicia Aram I delivered a prayer for peace and safety of Nagorno-Karabakh. It came days after the clashes between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces which were the deadliest since the ceasefire of 1994.[35][36][37]

On April 6, 2017 Serj Tankian, the lead singer of the rock band System of a Down performed the Christian liturgical prayer "Lord, have mercy" (Ter voghormia), in Armenian, at the cathedral.[38][39]

Architecture

The cathedral's church is a domed basilica with four apsides.[40] It is 34.7 m (114 ft) long and 23 m (75 ft) wide.[10][lower-alpha 3] Standing at a height of 35 m (115 ft),[10] it is one of the largest Armenian churches.[30][40][41] Its dome, the conical roof of which is metallic, is 17 m (56 ft) tall.[11][27] Artak Ghulyan criticized the proportions of the roof, restored by Volodya Babayan, as being unfaithful (too tall) to the original proportions.[42] The church has three identical entrances from the west, south and north. There are ornamental reliefs on the portals and windows.[11] The church's floor plan is an imitation of that of Etchmiadzin Cathedral, Armenia's mother church.[9][41][43] The cathedral is seen as having combined both innovative techniques and well-established traditions of Armenian architecture.[43]

Both the church and the bell tower are built of white limestone.[9][30][44] The freestanding bell tower has three floors (levels) and contains two bells, the larger of which was cast in Tula, Russia in 1857.[12] Sculptures of angels blowing trumpets stand on the top of its first floor.[40]

Significance

The cathedral, along with Gandzasar monastery, is a symbol of history and identity for the Armenians of Karabakh. Novelist Zori Balayan noted that it was often recalled during the emergence of the Karabakh movement.[24] It has become a symbol of liberation of the city as perceived by Armenians[45] and a popular pilgrimage site for Armenians from Armenia and the diaspora.[46] Catholicos Karekin II called the cathedral a symbol of the Armenian liberation movement of Artsakh during a mass at the cathedral in 2016.[47] Furthermore, it is seen as a remnant of the 19th and early 20th century religious-cultural renaissance of Shusha.[48]

Numerous manuscripts used to be kept at the cathedral,[11] the earliest dated 1612.[5] The Right Arm of Grigoris, the grandson of Gregory the Illuminator, was also kept at the church.[12]

References

Notes

- ↑ de facto controlled by the Republic of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh), de jure recognized as part of Azerbaijan

- ↑ Also spelled Ghazanchetzotz, Gazanchetsots (Russian: Газанчецоц), Kazanchetsots (Russian: Казанчецоц). In Azerbaijani: Kazançetsots/Qazançetsots[2] or Qazançı kilsəsi.[3]

- ↑ Alternatively given as 35 by 23 metres (115 by 75 ft).[9]

References

- 1 2 "Dioceses: Armenia". armenianchurch.org. Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin.

- ↑ de Waal, Thomas (2008). Qarabağ: Ermənistan və Azərbaycan sülh və savaş yollarında (Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War) (in Azerbaijani). Yusif Axundov (translator). Baku: “İlay” MMC. pp. 210, 216. ISBN 978-9952-25-086-2.

p. 208: ...Qazançetsots kilsəsində... p. 216: ...Kazançetsots kilsəsi...

- ↑ "Dünya əhəmiyyətli daşınmaz tarix və mədəniyyət abidələrinin Siyahısı (Memarlıq abidələri)" (PDF). mct.gov.az (in Azerbaijani). Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Azerbaijan. p. 12. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 Karapetyan, B. "Շուշի [Shushi]" (in Armenian). Yerevan State University Institute for Armenian Studies (via Ղարաբաղյան ազատագրական պատերազմ 1988-1994 (Karabakh Liberation War 1988-1994), 2004, Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing).

Արցախի թեմի առաջնորդանիստ Ղազանչեցոց Ս. Ամենափրկիչ մայր տաճարը (XIX դ.): Եկեղեցին գործել է մինչև 1930-ը, մասամբ նորոգվել 1981-1988-ին՝ մշեցի վերականգնող վարպետ Վ. Բաբայանի (ծ. 22.6.1937) ջանքերով: 1988-ին Շուշիի հայերին տեղահանելուց հետո ադրբեջանցիները ջարդել են զանգակատան հրեշտակների խորաքանդակները: 1998-ին ավարտվել է եկեղեցու զանգակատան նորոգումը և մեծ հանդիսությամբ օծվել հուլիսի 19-ին, որպես հայ առաքելական եկեղեցու Արցախի թեմի առաջնորդանիստ՝ Պարգև արքեպիսկոպոս Մարտիրոսյանի առաջնորդությամբ:

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vardanyan 1998, p. 114.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, p. 45.

- ↑ Walker, Edward (2000). "No War, No Peace in the Caucasus: Contested Sovereignty in Chechnya, Abkhazia, and Karabakh". In Bertsch, Gary K.; Craft, Cassady; Jones, Scott A.; Beck, Michael. Crossroads and Conflict: Security and Foreign Policy in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Routledge. p. 297. ISBN 0-415-92273-9.

...Shusha, along with Tbilisi (Tiflis), was at one time one of the two main Armenian cities of the Transcaucasus...

- ↑ Свод статистических данных о населении Закавказского края, извлечённых из посемейных списков 1886 года (in Russian). Tiflis. 1893. view online

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hasratyan 2002.

- 1 2 3 Mkrtchyan 1988, p. 183.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mkrtchian & Davtian 1999.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vardanyan 1998, p. 115.

- ↑ "Վերանորոգվում է Շուշիի Ս. Ամենափրկիչ եկեղեցին [Shushi's St. Savior Church is being renovated]". Etchmiadzin. 44 (11–12): 35. 1987.

- 1 2 Melik-Shahnazaryan, Levon (1997). "Армянская Культура – Объект Агрессии Азербайджана [Armenian Culture: An Object of Aggression by Azerbaijan]". Военные преступления Азербайджана против мирного населения НКР [Azerbaijani War Crimes Against the Peaceful Population of NKR]. Yerevan: Nairi.

Только за период 1988-91 гг. в Шуши трижды поджигали, обкладывая автомобильными покрышками, шедевр армянской архитектуры XIX века, церковь Газанчецоц Христа Спасителя. От великолепного строения фактически остался лишь каменный остов.

- ↑ Karapetyan, Samvel (2011). The State of Armenian Historical Monuments in Azerbaijan and Artsakh (PDF). Yerevan: Research on Armenian Architecture. p. 38. ISBN 978-9939-843-00-1.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, p. 190.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, pp. 179-180, 190.

- ↑ Gore, Patrick Wilson (2008). 'Tis Some Poor Fellow's Skull: Post-Soviet Warfare in the Southern Caucasus. iUniverse. p. 83. ISBN 9780595486793.

...the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral, which the shrewd Azeris had been using as their main ammunition depot, sure that it was safe from Armenian gunners.

- ↑ Cox, Caroline; Rogers, Benedict (2011). "Nagorno-Karabakh: 'We Must Always Love'". The Very Stones Cry Out: The Persecuted Church: Pain, Passion and Praise. A&C Black. p. 85. ISBN 9780826442727.

Soldiers had taken the now empty boxes which had contained the GRAD missiles out of the church...

- ↑ Goltz, Thomas (2015) [1998]. Azerbaijan Diary: A Rogue Reporter's Adventures in an Oil-rich, War-torn, Post-Soviet Republic. Routledge. p. 184. ISBN 9780765602435.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, p. 174.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, pp. 179-180.

- 1 2 3 Corley 1998, p. 331.

- 1 2 Corley 1998, p. 330.

- ↑ de Waal, Thomas (15 November 1997). "An Eccentric Outpost of Christianity". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017.

The only building being restored is the church of Gazanchetsots, Armenia's largest church.

- ↑ Vartivarian, Hagop (16 December 2011). "Overdue Recognition for Andreas Roubian". Armenian Mirror-Spectator.

Roubian, who is of Evangelical faith, became the benefactor of the Ghazanchetots Sourp Asdvadzadzin Cathedral of Shushi. He personally supervised and financed its reconstruction.

- 1 2 3 Vardanyan 1998, p. 116.

- ↑ "Ամենայն Հայոց Վեհափառ Հայրապետի Օրհնության գիրը Արցախի թեմի առաջնորդ գերաշնորհ Տ. Պարգև եպիսկոպոս Մարտիրոսյանին՝ Շուշիի Ս. Ամենափրկիչ Ղազանչեցոց եկեղեցու օծման առթիվ". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. 54 (7): 113–120. 1998.

- ↑ Antonyan, Yulia (2015). "Political power and church construction in Armenia". In Agadjanian, Alexander; Jödicke, Ansgar; van der Zweerde, Evert. Religion, Nation and Democracy in the South Caucasus. Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 9781317691570.

The reconstruction, or construction, of churches was perceived more as a cultural process aimed at a restoration of the Armenian cultural heritage, a spiritual and physical "rebirth" of the Armenian nation. Thus, among the first churches to be reconstructed were the Ghazanchetsots Cathedral in Shushi (Karabakh) and the Amenaprkich (Lord Saviour) Church at Gyumri. Both churches were rebuilt to symbolize the rebirth of the cities, one of which devastated during the war...

- 1 2 3 de Waal 2003, p. 185.

- ↑ Bardsley, Daniel (21 July 2009). "Shusha breathes new life after years of strife". The National. Abu Dhabi.

The city's Ghazanchetsots Cathedral has been restored since the conflict ended and is now one of the few pristine-looking buildings in the city.

- ↑ "Արցախի Ճերմակազգեստ Գեղեցկուհին [The While Beauty of Artsakh]". hushardzan.am (in Armenian). Service for the Protection of Historical Environment and Cultural Museum Reservations (Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Armenia). Archived from the original on 1 March 2017.

- ↑ "Karabakh's Big Wedding Day". Institute for War and Peace Reporting. 31 October 2008.

The couples were married in the churches of Gandzasar and Kazanchetsots in Shushi.

- ↑ Hayrapetyan, Anahit (23 October 2008). "Nagorno-Karabakh: Mass Wedding Hopes to Spark Baby Boom in Separatist Territory". EurasiaNet.

Five hundred and sixty couples ended up being married either at St. Ghazanchetsots church or the 13th century Gandzasar monastery, not far from Vank.

- ↑ "Հայոց երկու հայրապետները մաղթանք կատարեցին Շուշիի Ղազանչեցոց եկեղեցում". azatutyun.am (in Armenian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Շուշիի Ղազանչեցոց Սուրբ Ամենափրկիչ եկեղեցում Հանրապետական մաղթանք է կատարվե" (in Armenian). Armenpress. 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Երկու Վեհափառ Հայրապետները Շուշիի Ղազանչեցոց Ս. Ամենափրկիչ Եկեղեցւոյ Մէջ Հայրապետական Պատգամ Տուած Են". Aztag (in Armenian). Beirut. 15 April 2016.

- ↑ "Serj Tankian is singing "Lord, Have mercy" in Shushi: Civilnet". A1plus. 6 April 2017.

- ↑ ""Տեր, Ողորմեա"-ն՝ Թանկյանի կատարմամբ՝ Շուշիի Ղազանչեցոց եկեղեցում". civilnet.am (in Armenian). 6 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Hasratyan 1982.

- 1 2 Chorbajian, Levon; Mutafian, Claude; Donabedian, Patrick (1994). The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh. London: Zed Books. p. 84. ISBN 1-85649-287-7.

Thus when it was decided to construct the Cathedral of Our Savior, called Ghazanchetsots (one of the grandest churches in all of Armenia), in 1868–1888 in Shushi, it was to Etchmiadzin, the most important sanctuary for Armenians, that they looked for inspiration, at least for the plan.

- ↑ "Ղազանչեցոց Ամենափրկիչ եկեղեցու գմբեթի վեղարը խոստացավ վերականգնել ու չարեց". operativ.am (in Armenian). 10 May 2015. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018.

- 1 2 "A Brief History of the Art and Architecture of Artsakh — Nagorno Karabakh". nkrusa.org. Office of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic in the United States. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016.

Artsakh's architecture of the nineteenth century is distinguished by a merger of innovation and the tradition of grand national monuments of the past. One example is the Cathedral of the Holy Savior also known as Ghazanchetzotz (1868-1888). It stands in Artsakh's former capital of Shushi, and is among the largest Armenian churches ever erected. The cathedral's architectural forms were influenced by the designs of the ancient cathedral of St. Echmiadzin (4th-9th centuries), center of the Armenian Apostolic Church located to the west of Armenia's capital of Yerevan.

- ↑ Juskalian, Russ (21 September 2012). "Off the Map in the Black Garden". The New York Times.

...the Tolkienesque Ghazanchetsots Cathedral, built of white limestone.

- ↑ Hagopian, Michelle (26 September 2013). "Blog Posts from Armenia and Artsakh". Armenian Weekly.

But it has withstood war, and it symbolizes the liberation of Shushi and our people.

- ↑ "Shushi City of Artsakh attracts tourists from Armenia and Diaspora". news.am. 7 November 2014.

The rebuilt Temple St. Kazanchetsots is a popular place of pilgrimage for tourists from Armenia and the Diaspora.

- ↑ "Շուշիի Ղազանչեցոց Ս․ Ամենափրկիչ եկեղեցում կատարվեց Հանրապետական մաղթանք". Aravot (in Armenian). via Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. 9 September 2016.

...ազատագրական մեր պայքարի խորհրդանիշը հանդիսացող Շուշիի Սուրբ Ամենափրկիչ Ղազանչեցոց եկեղեցում...

- ↑ Tchilingirian, Hratch (1998). "Religious Discourse on the Conflict in Nagorno Karabakh" (PDF). Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe. George Fox University. 18 (4).

Between 1820 and 1930, Karabakh was a hub of vibrant religious and cultural life. [...] A remnant of this religious-cultural renaissance is the famous Cathedral of Our Saviour (1868-1887) in the Kazanchetsots neighborhood of Shushi (Lalayan 1988 and Ter Gasbarian 1993).

Bibliography

- Corley, Felix (1998). "The Armenian Church under the Soviet and independent regimes, part 3: The leadership of Vazgen". Religion, State and Society. Taylor & Francis. 26 (3–4): 291–355.

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-1945-9.

- Vardanyan, Mariam (1998). "Օծվեց Շուշիի Սուրբ Ամենափրկիչ Ղազանչեցոց եկեղեցին [Consecration of the Ghazanchetsots Holy Savior Cathedral of Shushi]". Etchmiadzin (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. 54 (7): 113–120.

- Hasratyan, Murad (2002). "Շուշիի Ղազանչեցոց Ս. Ամենափրկիչ Եկեղեցի [Ghazanchetsots S. All-Savior Church of Shushi]". In Ayvazyan, Hovhannes. "Քրիստոնյա Հայաստան" հանրագիտարան ["Christian Armenia" Encyclopedia] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing. view online

- Hasratyan, Murad (1982). "Շուշի. Ճարտարապետությունը [Shushi: Architecture]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume (in Armenian). Yerevan. p. 601.

- Mkrtchyan, Shahen (1988). "Церковь Казанчецоц [Ghazanchetsots Church]". Историко-архитектурные памятники Нагорного Карабаха [Historical and architectural monuments of Nagorno-Karabakh]. Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing. pp. 183–184.

- Mkrtchian, Shahen; Davtian, Schors (1999). "The Church of Ghazanchetsots". In Oskanian, Vartan. Shushi: The City of Tragic Fate. Yerevan: Amaras Publishing House. ISBN 9789993010050.