Fort Erie, Ontario

| Fort Erie Fort Érié (French) | |

|---|---|

| Town (lower-tier) | |

|

Town of Fort Erie Ville de Fort Érié (French) | |

The Peace Bridge between Fort Erie and Buffalo. | |

Location of Fort Erie within Niagara Region | |

Location in Ontario | |

| Coordinates: 42°55′N 79°01′W / 42.917°N 79.017°WCoordinates: 42°55′N 79°01′W / 42.917°N 79.017°W | |

| Country |

|

| Province |

|

| Regional Municipality | Niagara |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Wayne H. Redekop |

| • MP | Rob Nicholson |

| • MPP | Wayne Gates |

| Area[1] | |

| • Land | 166.27 km2 (64.20 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 30,710 |

| • Density | 184.7/km2 (478/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Forward Sortation Area | L2A |

| Area code(s) | 905, 289, 365 |

| Highways |

|

| Website | www.forterie.ca |

Fort Erie is a town on the Niagara River in the Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada. It is directly across the river from Buffalo, New York and is the site of Old Fort Erie which played a prominent role in the War of 1812.

Fort Erie is one of Niagara's fastest growing communities, and has experienced a high level of residential and commercial development in the past few years. Garrison Road (Niagara Regional Road 3) is the town's commercial corridor, stretching east to west through Fort Erie.

Fort Erie is also home to other commercial core areas (Bridgeburg, Ridgeway, Stevensville and Crystal Beach) as a result of the 1970 amalgamation of Bertie Township and the village of Crystal Beach with Fort Erie.

Crystal Beach Amusement Park occupied waterfront land at Crystal Beach, Ontario from 1888 until the park's closure in 1989. The beach is part of Fort Erie.[2]

Geography

Fort Erie is generally flat, but there are low sand hills, varying in height from 2 to 15 metres (6.6 to 49.2 ft), along the shore of Lake Erie, and a limestone ridge extends from Point Abino to near Miller's Creek, giving Ridgeway its name. The soil is shallow, with a clay subsoil.

The town's beaches on Lake Erie, most notably Erie Beach, Crystal Beach and Bay Beach, are considered the best in the area and draw many weekend visitors from the Toronto and Buffalo, New York areas. While summers are enjoyable, winters can occasionally be fierce, with many snowstorms, whiteouts and winds coming off Lake Erie.

Communities

In addition to the primary urban core of Fort Erie, the town also contains the neighbourhoods of Black Creek, Bridgeburg/NorthEnd/Victoria, Crescent Park, Crystal Beach, Point Abino, Ridgeway, Snyder, and Stevensville. Smaller and historical neighbourhoods include Amigari Downs, Bay Beach, Buffalo Heights, Douglastown, Edgewood Park, Erie Beach, Garrison Village, Mulgrave, Oakhill Forest, Ridgemount, Ridgewood, Rose Hill Estates, Thunder Bay, Walden, Wavecrest and Waverly Beach.

Fort Erie Secondary School and Ridgeway-Crystal Beach High School were two public high schools serving Fort Erie and area communities until September 2017 when Greater Fort Erie Secondary School opened on Garrison road the first new high school since 1971 in the region.

Climate

| Climate data for Fort Erie (1981−2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59) |

16.5 (61.7) |

25.0 (77) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

35.5 (95.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

22.5 (72.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

35.5 (95.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

26.1 (79) |

25.5 (77.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.0 (59) |

8.7 (47.7) |

2.8 (37) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.1 (24.6) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.4 (32.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

12.7 (54.9) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8 (18) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

1.4 (34.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

12.8 (55) |

16.1 (61) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.1 (34) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.5 (−19.3) |

−31 (−24) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

−12 (10) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

1.0 (33.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−1 (30) |

−6.1 (21) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−31 (−24) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 78.9 (3.106) |

66.6 (2.622) |

71.0 (2.795) |

78.8 (3.102) |

93.2 (3.669) |

81.7 (3.217) |

84.7 (3.335) |

88.5 (3.484) |

105.4 (4.15) |

96.7 (3.807) |

102.8 (4.047) |

103.2 (4.063) |

1,051.3 (41.39) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 34.2 (1.346) |

32.8 (1.291) |

44.7 (1.76) |

74.4 (2.929) |

92.3 (3.634) |

81.7 (3.217) |

84.7 (3.335) |

88.5 (3.484) |

105.4 (4.15) |

95.3 (3.752) |

89.9 (3.539) |

52.5 (2.067) |

876.3 (34.5) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 44.7 (17.6) |

33.8 (13.31) |

26.3 (10.35) |

4.4 (1.73) |

0.9 (0.35) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

1.4 (0.55) |

12.9 (5.08) |

50.7 (19.96) |

175.0 (68.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 15.8 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 13.2 | 13.0 | 11.4 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 11.4 | 12.9 | 14.7 | 15.2 | 152.3 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.9 | 5.0 | 7.9 | 12.3 | 13.0 | 11.4 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 11.4 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 7.9 | 120.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 10.6 | 8.0 | 5.4 | 1.5 | 0.08 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.08 | 2.9 | 8.2 | 36.6 |

| Source: Environment Canada[3] | |||||||||||||

History

The Fort Erie area contains deposits of flint,[4] and became important in the production of spearheads, arrowheads, and other tools. In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the Niagara Peninsula was inhabited by the Neutral Nation, so named by the French because they tried to remain neutral between the warring Huron and Iroquois peoples. In 1650, during the Beaver Wars, the Iroquois Confederacy declared war on the Neutral Nation, driving them from their traditional territory by 1651, and practically annihilating them by 1653.

After the Treaty of Paris, which ended the French and Indian War and transferred Canada from France to Britain, King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, establishing a "proclamation line", the territory beyond which (including what is now Southern Ontario) would be an Indian Reserve. This was an attempt to avoid further conflict with the Indians, although it did not forestall Pontiac's War the following year. The British also built a string of military forts to defend their new territory, including Fort Erie, the first version of which was established in 1764.

During the American Revolution Fort Erie was used as a supply depot for British troops. After the war the territory of what is now the Town of Fort Erie was settled by soldiers demobilised from Butler's Rangers, and the area was named Bertie Township in 1784.

The original fort, built in 1764, was located on the Niagara River's edge below the present fort. It served as a supply depot and a port for ships transporting merchandise, troops and passengers via Lake Erie to the Upper Great Lakes.[5] The fort was damaged by winter storms and in 1803, plans were made for a new fort on the higher ground behind the original. It was larger and made of flintstone but was not quite finished at the start of the War of 1812.[6][5]

During the war, the Americans attacked Fort Erie twice in 1812, captured and abandoned it in 1813, and then recaptured it in 1814. The Americans held it for a time, breaking a prolonged British siege. Later they destroyed Fort Erie and returned to Buffalo in the winter of 1814.

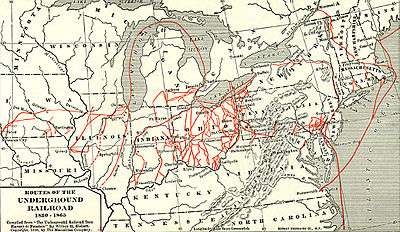

The Fort Erie area became a major terminus for slaves using the Underground Railroad (between 1840 and 1860); many had crossed into Canada from Buffalo, New York. Bertie Hall (which was used for a time in the 20th century as a Doll House Museum) may have been a stopping point on the Underground Railroad although some sources dispute this as a "legend".[7][8]

In 1866, during the Fenian raids, between 1,000 and 1,500 Fenians crossed the Niagara River, occupied the town and demanded food and horses. The only payment they were able to offer was Fenian bonds; these were not acceptable to the citizens. The Fenians then cut the telegraph wires and tore up some railway tracks. Afterwards, they marched to Chippewa and the next day to Ridgeway where they fought the Battle of Ridgeway, a series of skirmishes with the Canadian militia.[9] The Fenians then returned to Fort Erie and fought the Battle of Fort Erie, defeating the Canadian militia. Fearing British reinforcements, they then decided to retreat to the U.S.[10][11]

In 1869 the population was 1,000 and Fort Erie was served by the Grand Trunk and the Erie & Niagara railways. The Grand Trunk Railway built the International Railway Bridge in 1873, bringing about a new town, originally named Victoria and subsequently renamed to Bridgeburg, north of the original settlement of Fort Erie. By 1876, Ridgeway had an estimated population of 800, the village of Fort Erie has an estimated population of 1,200, and Victoria boasted three railway stations.[12] By 1887, Stevensville had an estimated population of "nearly 600", Victoria of "nearly 700", Ridgeway of "about 600", and Fort Erie of "about 4,000".[13]

In 1888, the amusement park at Crystal Beach opened. From 1910, the steamship Canadiana (and until 1929, the steamship SS Americana) brought patrons from Buffalo until 1956. The park continued to operate until it closed in 1989. A gated community was built in this area.[14][15]

In 1904, a group of speculators bought land at Erie Beach, planning to build an amusement park and other amenities, and sell lots around the park to vacationers from Buffalo. Erie Beach featured a hotel, a casino, a race track, regular ferry service from Buffalo and train service from the ferry dock in Fort Erie, and what was billed as the world's largest outdoor swimming pool. Erie Beach and Crystal Beach were in competition to provide bigger thrills to patrons, until Erie Beach went bankrupt during the Depression and closed down on Labour Day weekend, 1930.[16]

The Niagara Movement meeting was held at the Erie Beach Hotel[17] in 1905. The movement later led to the founding of the NAACP.

The Point Abino Light Tower was built by the Canadian government in 1918. The lighthouse has been automated in 1989. Since its decommissioning in 1995, the Point Abino Lighthouse was designated as a National Historic Site. The lighthouse is now owned by the Town of Fort Erie and is available for weekend tours in the summer.

On August 7, 1927 the Peace Bridge was opened between Fort Erie and Buffalo.

On January 1, 1932, Bridgeburg and Fort Erie amalgamated into a single town.

The ruins of Fort Erie remained until they were rebuilt through a depression era "work program" project, as a tourist attraction. Work started in 1937, and the fort was opened to the public in 1939.

In 1970, the provincial government consolidated the various villages in what had been Bertie Township, including the then town of Fort Erie, into the present Town of Fort Erie.

Demographics

The 2016 Census of Canada indicates a current population of 30,710 for Fort Erie. This is a 2.5% increase over the last Census (2011).[1] The median household income in 2005 for Fort Erie was $47,485.00, which is below the Ontario provincial average of $60,455.00.[18]

| Canada 2006 Census | Population | % of Total Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minority group Source:[19] |

South Asian | 225 | 0.8% |

| Chinese | 365 | 1.2% | |

| Black | 300 | 1% | |

| Filipino | 50 | 0.2% | |

| Latin American | 410 | 1.4% | |

| Arab | 40 | 0.1% | |

| Southeast Asian | 45 | 0.2% | |

| West Asian | 30 | 0.1% | |

| Korean | 85 | 0.3% | |

| Japanese | 20 | 0.1% | |

| Other visible minority | 35 | 0.1% | |

| Mixed visible minority | 20 | 0.1% | |

| Total visible minority population | 1,620 | 5.5% | |

| Aboriginal group Source:[20] | First Nations | 750 | 2.5% |

| Métis | 150 | 0.5% | |

| Inuit | 0 | 0% | |

| Total Aboriginal population | 940 | 3.2% | |

| White | 26,985 | 91.3% | |

| Total population | 29,545 | 100% | |

| Census | Population |

|---|---|

| 1871 | 835 |

| 1901 | 890 |

| 1911 | 1,146 |

| 1921 | 1,546 |

| 1931 | 2,383 |

| 1941 | 6,566 |

| 1951 | 7,572 |

| 1961 | 9,027 |

| 1971 | 23,113 |

| 1981 | 24,096 |

| 1991 | 26,006 |

| 2001 | 28,143 |

| 2006 | 29,925 |

| 2011 | 29,960 |

| 2016 | 30,710 |

According to the 2001 census, the population was 28,143, broken down as follows: 92.8% White, 3.2% Aboriginal, 1.4% Chinese, 0.9% Black, and a very small percentage of Asian, Arab, and Hispanic populations.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Highway access

Fort Erie has been the Niagara terminus of the Queen Elizabeth Way since 1937. Road traffic continues to Buffalo, New York across the Peace Bridge, which was built in 1927.

Fort Erie was the Eastern terminus of King's Highway 3A from 1927 to 1929, and Ontario Highway 3 from 1929 until 1998, when the portion of Highway 3 within Fort Erie was downloaded to the Regional Municipality of Niagara and redesignated as Niagara Regional Road 3. Within Fort Erie, Highway 3 is named Garrison Road, and is the major East-West connection through the town. Dominion Road was designated as King's Highway 3C from 1934 until 1970, when it was downloaded to the newly formed Regional Municipality of Niagara and redesignated as Niagara Regional Road 1.

Fort Erie is the Southern Terminus of the Niagara Parkway, which extends from Fort Erie to Fort George.

Public transit

Public transit is provided by Fort Erie Transit, which operate buses in town and connecting to other Niagara municipalities.[21]

Niagara Falls Transit operates a service from Niagara Falls into Fort Erie, connecting with the Fort Erie Transit bus at Wal Mart Plaza at 750 Garrison Road.[22]

Intercity transit

Private intercity coach services are primarily operated by Coach Canada and Greyhound, with connections to Hamilton and Toronto and to US destinations via Buffalo.[23] The terminus is located at Robo Mart, 21 Princess Street at Waterloo Street.

The International Railway Bridge was built in 1873, and connects Fort Erie to Buffalo, New York across the Niagara River. There is currently no passenger rail service to Fort Erie.

Waterways

Fort Erie is at the outlet of Lake Erie into the Niagara River. The lake and river serve as a playground for numerous personal yachts, sailboats, power boats and watercraft. There is a marina at the site of a former shipyard at Miller's Creek on the Niagara River, and a boat launch ramp in Crystal Beach.

Prior to the completion of the two bridges, passengers and freight were carried across the river by ferry.

From 1829, when the Welland Canal first opened, to 1833, when the cut was completed to Port Colborne, ship traffic between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario would transit the upper Niagara River.

Utilities

In order to reduce large-scale ice blockage in the Niagara River, with resultant flooding, ice damage to docks and other waterfront structures, and blockage of the water intakes for the hydro-electric power plants at Niagara Falls, the New York Power Authority and Ontario Power Generation have jointly operated the Lake Erie-Niagara River Ice Boom since 1964. The boom is installed on December 16, or when the water temperature reaches 4 °C (39 °F), whichever happens first. The boom is opened on April 1 unless there is more than 650 square kilometres (250 sq mi) of ice remaining in Eastern Lake Erie. When in place, the boom stretches 2,680 metres (8,790 ft) from the outer breakwall at Buffalo Harbor almost to the Canadian shore near the ruins of the pier at Erie Beach in Fort Erie. Originally, the boom was made of wooden timbers, but these have been replaced by steel pontoons.[24]

Sports and recreation

Attractions

- Fort Erie Race Track

- Old Fort Erie

- Point Abino Lighthouse

- Safari Niagara[25]

Hiking

Fort Erie is the Eastern terminus of the Friendship Trail, and the Southern terminus of the Niagara River Recreation Pathway. Both trails are part of the Trans-Canada Trail system.

Parks

Mather Arch Park, located just to the south of the Peace Bridge, is on land donated by American citizen Alonzo C. Mather in tribute to the peace and friendship between Canada and the United States. The park contains Mather Arch, which was built largely due to donations by Mather, originally dedicated by the Niagara Parks Commission in 1939, and restored in 2000 as a millennium project. There is also a memorial statue to those from Fort Erie who died in World War I, World War II, and the Korean War.[26]

Sports

Baseball

- Oakes Park, a five diamond complex off Central Avenue, is the home field of the Fort Erie Cannons, who compete in the Niagara District Baseball Association's senior men's league.

Golf

- Bridgewater Country Club on Gilmore Road.

- Cherry Hill Club is a private club in Ridgeway.

- Fort Erie Golf Club on Garrison Road.

- International Country Club of Niagara in Stevensville.

- Rio VIsta Golf on Crooks Street.

Hockey

- The Fort Erie Leisureplex on Garrison Road is the home rink of the Fort Erie Meteors.

- The Crystal Ridge Arena in Crystal Beach hosts a number of hockey and figure skating clubs.

Soccer

- Fort Erie Sting Competitive and new PSL over 18 team

- Thriving youth house league program

- Club at Ferndale Park, on Fendale Ave in Crescent Park, with washroom facilities. Two full fields, two mid fields/four minifields

- Optimist Park, Bowen Rd at Petit Rd., two full fields with lights, two midfields/four minifields

Current teams

| Team | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fort Erie Meteors | Greater Ontario Junior Hockey League | Ice hockey | Fort Erie Leisureplex | 1957 | 0 (1 in previous leagues) |

| Fort Erie Cannons | Niagara District Baseball Association | Baseball | Oakes Park | 2005 | 2 |

Notable people

- Sandy Annunziata, professional football player, two time Grey Cup Champion; was born in Fort Erie and currently serves as the town's Regional Councillor.

- Ernest Alexander Cruikshank, Brigadier General and historian; was born in Bertie Township.

- Billy Dea, professional hockey player, lived in Crystal Beach with his wife Sally and son Derrick for a large part of his professional career.

- Michael Fonfara, keyboard player; was born in Stevensville.

- Paul Gardner, professional hockey player; was born in Fort Erie.

- Douglas Kirkland, photographer.

- James L. Kraft, entrepreneur and inventor; was born outside of Stevensville and worked in Fort Erie before emigrating to the United States.

- Shane Lindstrom (professionally known as Murda Beatz), record producer.

- Pierre Pilote, professional hockey player; lived in Fort Erie for most of his adolescence.

- Ron Sider, theologian and social activist; was born in Stevensville.

- Nick Weglarz, professional baseball player; was born in Stevensville.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 2016 Census Profile

- ↑ "Crystal Beach". forteriecanada.com. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Fort Erie, Ontario". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ↑ Old Fort Erie: History Archived 2010-08-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Old Fort Erie History ". Niagara Parks, Canada. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-04-28. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ↑ Calarco, Tom; Vogel, Cynthia; Grover, Kathryn; Hallstrom, Rae; Pope, Sharron; Waddy-Thibodeaux, Melissa (2011). Places of the Underground Railroad: A Geographical Guide. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-313-38147-8.

- ↑ Calarco, Tom (2014). "Chapter 13: Was Your House a Stop on the Underground Railroad?". The Search for the Underground Railroad. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-62584-954-0.

- ↑ "The Fenian Raid 1866". The Queen's Own Rifles. Archived from the original on 2005-08-30. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "The Fenian Raid 1866". The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada Regimental Museum and Archives. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ For the figure of 850, see: H.W. Hemans to Lord Monck, telegram June 3, 1866, in [s.n.] Correspondence Relating to the Fenian Invasion and Rebellion of the Southern States, Ottawa: 1869. p. 142; also Colonel Lowry, Report, June 4, 1866, Miscellaneous Records Relating to the Fenian Raids, British Military and Naval Records "C" Series, RG8-1, Volume 1672; Microfilm reel C-4300, p. 282. (Public Archives of Canada)

- ↑ Bertie Township

- ↑ The Township Papers of Bertie Township, Welland County

- ↑ "Crystal Beach Amusement Park". exploringniagara.com. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "S.S. Canadiana Facts". sscanadiana.com. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Erie Beach Amusement Park". exploringniagara.com. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Niagara Movement First Annual Meating" (PDF). University of Massachusetts. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ "Fort Erie, Ontario - Detailed City Profile". Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ "Community Profiles from the 2006 Census". Statistics Canada - Census Subdivision. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ "Aboriginal Peoples - Data table". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ Transit Schedule

- ↑ For Erie Fall Service Update

- ↑ "Getting Around Fort Erie". world66.com. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Lake Erie–Niagara River Ice Boom Information Sheet" (PDF). The International Niagara Board of Control of the International Joint Commission. November 1999. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "About - Safari Niagara". Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- ↑ "Historic Plaques & Markers". Niagara Park Commission. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Erie, Ontario. |