Finnish markka

| Finnish markka | |

|---|---|

|

Suomen markka (Finnish) finsk mark (Swedish) | |

1983 1 markka | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | FIM |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | penni |

| Plural |

markkaa (Finnish partitive sg.) mark (Swedish) |

| penni |

penniä (Finnish partitive sg.) penni (Swedish) |

| Symbol | mk |

| penni | p |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | 10 mk, 20 mk, 50 mk, 100 mk, 500 mk |

| Rarely used | 1000 mk |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | 10 p, 50 p, 1 mk, 5 mk, 10 mk |

| Rarely used | 1 p (until 1979), 5 p and 20 p (until 1990) |

| Demographics | |

| User(s) |

None, previously: |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Bank of Finland |

| Website |

www |

| Valuation | |

| ERM | |

| Since | 14 October 1996 |

| Fixed rate since | 31 December 1998 |

| Replaced by €, non cash | 1 January 1999 |

| Replaced by €, cash | 1 January 2002 |

| € = | 5.94573 mk |

|

This infobox shows the latest status before this currency was rendered obsolete. | |

The Finnish markka (Finnish: Suomen markka, abbreviated mk, Swedish: finsk mark, currency code: FIM) was the currency of Finland from 1860 until 28 February 2002, when it ceased to be legal tender. The markka was replaced by the euro (€), which had been introduced, in cash form, on 1 January 2002, after a transitional period of three years when the euro was the official currency but only existed as 'book money'. The dual circulation period – when both the Finnish markka and the euro had legal tender status – ended on 28 February 2002.

The markka was divided into 100 pennies (Finnish: penni, with numbers penniä, Swedish: penni), postfixed "p". At the point of conversion, the rate was fixed at €1 = 5.94573 mk.

History

The markka was introduced in 1860[1] by the Bank of Finland, replacing the Russian ruble at a rate of four markkaa to one ruble. Senator Fabian Langenskiöld is called "father of markka". In 1865 the markka was separated from the Russian ruble and tied to the value of silver.[2] From 1878 to 1915, Finland adopted the gold standard of the Latin Monetary Union.[3] Before markka there were Swedish riksdaler and Russian ruble used side-by-side for a time.

Up to World War 1, the value of the markka fluctuated within +23%/−16% of its initial value, but with no trend. However, the markka suffered heavy inflation (91%) during 1914–18.[4] Gaining independence in 1917, Finland returned to the gold standard from 1926 to 1931.[3] Prices remained stable until 1940.[4] but the markka suffered heavy inflation (17% annually on average[4]) during the war years and then up to 1926, and again in 1956–57 (11%).[4] In 1963 the markka was replaced by the new markka, equivalent to 100 old markkaa.

Finland joined the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1948. The value of markka was pegged to the dollar at 320 mk/US$, which became 3.20 new mk/US$ in 1963 and devalued to 4.20 mk/US$ in 1967. After the breakdown of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971, a basket of currencies became the new reference. Inflation was high (over 5%) during 1971–85.[4] Occasionally, devaluation was used, 60% in total between 1975 and 1990, allowing the currency to more closely follow the depreciating US dollar than the rising German mark. The paper industry, which mainly traded in US dollars, was often blamed for demanding these devaluations to boost their exports. Various economic controls were removed and the market was gradually liberalized throughout the 1980s and the 1990s.

The monetary policy called "strong markka policy" (vahvan markan politiikka) was a characteristic feature of the 1980s and early 1990s. The main architect of this policy was President Mauno Koivisto, who opposed floating the currency and devaluations. As a result, the nominal value of markka was extremely high and in the year 1990, Finland was nominally the most expensive country in the world according to OECD's Purchasing Power Parities report.[5]

Koivisto's policy was maintained only briefly after Esko Aho was elected Prime Minister. In 1991, the markka was pegged to the currency basket ECU, but the peg had to be withdrawn after two months with a devaluation of 12%. In 1992, Finland was hit by a severe recession, the Early 1990s depression in Finland. It was caused by several factors, the most severe being the incurring of debt, as the 1980s economic boom was based on debt. Also, the Soviet Union had collapsed, which brought an end to bilateral trade, and existing trade connections were severed. The most important source of export revenue, Western markets, were also depressed during the same time, in part due to the war in Kuwait. As a result, by some opinions years overdue, the artificial fixed exchange rate was abandoned and the markka was floated.[6] Its value immediately decreased 13% and the inflated nominal prices converged towards German levels. In total, the value of the markka had decreased 40% as a result of the recession. Also, as a result, several entrepreneurs who had borrowed money denominated in foreign currency suddenly faced insurmountable debt.[7]

Inflation was low during the markka's independent existence as a floating currency (1992–1999): 1.3% annually on average.[4] The markka was added into the ERM system in 1996 and then became a fraction of the euro in 1999, with physical euro money arriving later in 2002. It has been speculated that if Finland had not joined the euro, market fluctuations such as the dot-com bubble would have reflected as wild fluctuations in the price of the markka. (Nokia, formerly traded in markkas, was in 2000 the European company with the highest market capitalization.[8] )

Names

The name "markka" was based on a medieval unit of weight. Both "markka" and "penni" are similar to words used in Germany for that country's former currency, based on the same roots as the German Mark and pfennig.

Although the word "markka" predates the currency by several centuries, the currency was established before being named "markka". A competition was held for its name, and some of the other entries included "sataikko" (meaning "having a hundred parts"), "omena" (apple) and "suomo" (from "Suomi", the Finnish name for Finland).

With numbers, Finnish does not use plurals but partitive singular forms: "10 markkaa" and "10 penniä" (the nominative is penni). In Swedish, the singular and plural forms of mark and penni are the same.

When the euro replaced the markka, mummonmarkka "grandma's markka" (sometimes shortened to just mummo) became a new slang term for the old currency. The sometimes used "old markka" can be misleading, since it can also be used to refer to the pre-1963 markka.

In Helsinki slang, a hundred markkaa was traditionally called huge [hu.ge] (from Swedish hundra "hundred"). After the 1963 reform this name was used for one new markka.

Coins

First markka

When the markka was introduced, coins were minted in copper (1, 5 and 10 penniä), silver (25 and 50 penniä, 1 and 2 markkaa) and gold (10 and 20 markkaa). After the First World War, silver and gold issues were ceased and cupro-nickel 25 and 50 penniä and 1 markka coins were introduced in 1921, followed by aluminium-bronze 5, 10 and 20 markkaa between 1928 and 1931. During the Second World War, copper replaced cupro-nickel in the 25 and 50 penniä and 1 markka, followed by an issue of iron 10, 25 and 50 penniä and 1 markka. This period also saw the issue of holed 5 and 10 penniä coins.

| Denomination | Years | Image | Material | Size | Obverse | Reverse | Designer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 markka | 1921–24 | Cupro-nickel | 24 mm | Rampant lion and date | Denomination flanked by branches | Isak Sundell | ||

| 1928–40 | Cupro-nickel | 21 mm | ||||||

| 1940–51 | Copper | 21 mm | ||||||

| 1943–44 | Iron | 21 mm | ||||||

| 5 markkaa | 1928–46 | Aluminum-bronze | 23 mm | Wreath and denomination | Shielded arms within wreath and date | Isak Sundell | ||

| 1946–52 | Brass | 23 mm | ||||||

| 10 markkaa | 1928–39 | Aluminum-bronze | 27 mm | Wreath and denomination | Shielded arms within wreath and date | Isak Sundell | ||

| 20 markkaa | 1928–39 | Aluminum-bronze | 31 mm | Wreath and denomination | Shielded arms within wreath and date | Isak Sundell | ||

All coins below 1 markka had ceased to be produced by 1948. In 1952, a new coinage was introduced, with smaller iron (later nickel-plated) 1- and 5=markka coins alongside aluminium-bronze 10-, 20- and 50-markka coins and (from 1956) silver 100- and 200-markka denominations. This coinage continued to be issued until the introduction of the new markka in 1963.

Second markka

1st series

The new markka coinage consisted initially of six denominations: 1 (bronze, later aluminium), 5 (bronze, later aluminium), 10 (aluminium-bronze, later aluminium), 20 and 50 penniä (aluminium-bronze) and 1 markka (silver, later cupro-nickel). From 1972, aluminium-bronze 5 markka were also issued.

2nd series

The last series of Finnish markka coins included five coins (listed with final euro values, rounded to the nearest cent):

- 10 penniä (silver-coloured) – a honeycomb on the reverse and a lily of the valley flower on the obverse = €0.02

- 50 penniä (silver-coloured) – haircap moss on the reverse and a bear on the obverse = €0.08

- 1 markka (copper-coloured) – the Finnish coat of arms on the obverse = €0.17

- 5 markkaa (copper-coloured) – a lily pad leaf and a dragonfly on the reverse and a Saimaa seal on the obverse = €0.84

- 10 markkaa (two-metal coin, copper-coloured centre and silver-coloured edge) – rowan tree branches and berries on the reverse and a wood grouse on the obverse = €1.68

Banknotes

This section covers the last design series of the Finnish markka, designed in the 1980s by Finnish designer Erik Bruun and issued in 1986.

| Denomination | Value in Euro (€) | Image | Main colour | Obverse | Reverse | Remark | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 markkaa | €1.68 |  |

|

Blue | Paavo Nurmi (1897–1973), athlete and Olympic winner | Helsinki Olympic Stadium | Discontinued upon the introduction of the 20-markkaa note in 1993. |

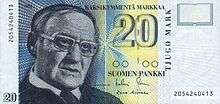

| 20 markkaa | €3.36 |  |

|

Blue | Väinö Linna (1920–1992), author and novelist | Tammerkoski | Introduced in 1993 to replace the 10-markkaa note. |

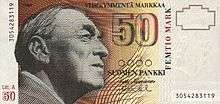

| 50 markkaa | €8.41 |  |

|

Brown | Alvar Aalto (1898–1976), architect | Finlandia Hall | |

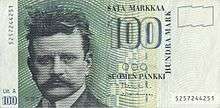

| 100 markkaa | €16.82 |  |

|

Green | Jean Sibelius (1865–1957), composer | Swans | |

| 500 markkaa | €84.09 |  |

|

Red | Elias Lönnrot (1802–1884), compiler of Kalevala | Forest hiking trail | |

| 1,000 markkaa | €168.19 |  |

|

Blue/purple | Anders Chydenius (1729–1803), priest and statesman | Kuninkaanportti gate in Suomenlinna | |

| 5,000 markkaa | €840.94 | Red/purple | Mikael Agricola (1510–1557), priest and linguist | Turku Cathedral | The note was never introduced. It was only a backup plan for inflation.[9] | ||

In this final banknote series, Bank of Finland used a photograph of Väinö Linna on the 20-markkaa note without permission from copyright holders. This was only revealed after several million notes were in use. The Bank paid 100,000 mk (€17,000) compensation to the rights holders.[10]

The second-to-last banknote design series, designed by Tapio Wirkkala, was introduced in 1955 and revised in the reform of 1963. It was the first series to depict actual specific persons. These included Juho Kusti Paasikivi on the 10 markkaa, K. J. Ståhlberg on the 50 markkaa, J. V. Snellman on the 100 markkaa and Urho Kekkonen on the 500 markkaa (introduced later). Unlike Erik Bruun's series, this series did not depict any other real-life subjects, but only abstract ornaments in addition to the depictions of people. A popular joke at the time was to cover Paasikivi's face except for his ear and back of the head on the 10-markka note, ending up with something resembling a mouse, said to be the only animal illustration in the entire series.

The still-older notes, designed by Eliel Saarinen, were introduced in 1922. They also depicted people, but these were generic men and women, and did not represent any specific individuals. The fact that these men and women were depicted nude caused a minor controversy at the time.

Coins and banknotes that were legal tender at the time of the markka's retirement could be exchanged for euros until February 29, 2012.

See also

References

- ↑ "Pankinjohtaja Sinikka Salon puhe Snellman ja Suomen markka -näyttelyn avajaisissa Suomen Pankin rahamuseossa". Suomen Pankki. 2006-01-10. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- ↑ Klinge, Matti. "Snellman, Johan Vilhelm (1806 - 1881)". The National Biography of Finland. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- 1 2 Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich, Jaime Reis, and Gianne Toniolo, The Emergence of Modern Central Banking from 1918 to the Present, table 4.2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nordean rahanarvokerroin.

- ↑ Wall Street Journal

- ↑ Genberg, Hans: Monetary Policy Strategies after EU Enlargement. Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva, Switzerland, 2 February 2004. Accessed 7 February 2009.

- ↑ http://www.barrikadi.fi/artikkelit/kun-oikeutta-ohjattiin

- ↑ "Finnish Consumer Prices are the highest in OECD". Wall Street Journal. 14 January 1992.

- ↑ Kaartamo, Outi: Raha on kaunista. Helsingin Sanomat monthly supplement, April 2010, pp. 83–88.

- ↑ Luukka, Teemu (2006-09-27). "Suomen Pankki maksoi korvauksia valokuvasta 17 000 euroa" (in Finnish). HS. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

External links

- Overview of markka from the BBC

- Historical Finnish banknotes and coins at the Bank of Finland

- Main outlines of Finnish history-thisisFINLAND

- History of the Finnish Markka (1860–2002)

- Historical banknotes from Finland (in English) (in German)

| Preceded by Russian ruble |

Finnish currency 1860–2002 |

Succeeded by euro |

.jpg)