Fidesz

Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance Fidesz – Magyar Polgári Szövetség | |

|---|---|

| |

| President | Viktor Orbán |

| Vice Presidents |

Gergely Gulyás Gábor Kubatov Szilárd Németh Katalin Novák |

| Parliamentary leader | Máté Kocsis |

| Founded | 30 March 1988 |

| Headquarters | 1088 Budapest, VIII. Szentkirályi Street 18. |

| Youth wing | Fidelitas |

| Ideology |

Hungarian nationalism[1][2] National conservatism[3][4][5] Social conservatism[6] Soft Euroscepticism[7][8] Right-wing populism[5][4][9] Christian democracy[10] Economic nationalism[11] |

| Political position | Right-wing[12][13][14] |

| National affiliation | Fidesz–KDNP |

| European affiliation | European People's Party |

| International affiliation |

International Democrat Union Centrist Democrat International |

| European Parliament group | European People's Party |

| Colours | Orange |

| National Assembly |

117 / 199 |

| European Parliament |

11 / 21 |

| County Assemblies |

245 / 419 |

| Party flag | |

.svg.png) | |

| Website | |

| www.fidesz.hu | |

Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈfidɛs]; in full, Hungarian: Fidesz – Magyar Polgári Szövetség) is a national-conservative[3][4][5] and right-wing populist[5][4][9] political party in Hungary. It has dominated Hungarian politics on the national and local level since its landslide victory in the 2010 national elections on a joint list with the Christian Democratic People's Party,[15] securing it a parliamentary supermajority that it retained in 2014[16][17] and again in 2018.[18] Fidesz also enjoys majorities in the county legislatures (19 of 19), almost all (20 of 23) urban counties and in the Budapest city council. Viktor Orbán has been the leader of the party for most of its history.

History

The party was founded in 1988, named simply Fidesz (Fiatal Demokraták Szövetsége, meaning the Alliance of Young Democrats), originally as a youthful classical liberal party. Fidesz was founded by young democrats, mainly students, who were persecuted by the communist party and had to meet in small, clandestine groups. The movement became a major force in many areas of modern Hungarian history. The membership had an upper age limit of 35 years (this requirement was abolished at the 1993 congress).

In 1989, Fidesz won the Rafto Prize. The Hungarian youth opposition movement was represented by one of its leaders, Dr Péter Molnár, who became a Member of Parliament in Hungary. In 1992, Fidesz joined the Liberal International.[19] At that time, it was a moderate liberal centrist party.

After its disappointing result in the 1994 elections, Fidesz changed its political position from liberal to conservative.[5][19] In 1995, it added "Hungarian Civic Party" (Magyar Polgári Párt) to its shortened name. The conservative turn caused a severe split in the membership. Péter Molnár left the party, as well as Gábor Fodor and Klára Ungár, who joined the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats.

Fidesz gained power in 1998 under leader and Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who governed Hungary in coalition with the smaller Hungarian Democratic Forum and the Independent Smallholders' Party. In 2000, Fidesz joined the European People's Party and had its membership in the Liberal International terminated.[19]

Fidesz narrowly lost the 2002 elections to the Hungarian Socialist Party, by 41.07% to the Socialists' 42.05%. Fidesz had 169 members of the Hungarian National Assembly, out of a total of 386. Following the defeat, the municipal elections in October saw huge Fidesz losses.

In the spring of 2003, Fidesz took its current name, "Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Union".[19]

It was the most successful party in the 2004 European Parliamentary Elections: it won 47.4% of the vote and 12 of its candidates were elected as Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), including Lívia Járóka, the second Romani MEP.

The election of Dr. László Sólyom as the new President of Hungary as the most recent success of the party. He was endorsed by Védegylet, an NGO including people from the whole political spectrum. His activity does not entirely overlap with the conservative ideals and he championed for elements of both political wings with a selective, but conscious choice of values.[20]

In 2005, Fidesz and the Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP) formed an alliance for the 2006 elections. Despite winning 42.0% of the list votes and 164 representatives out of 386 in National Assembly, they were beaten by the social-democratic and liberal coalition of Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) and the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ).

On 1 October 2006 Fidesz won the municipal elections, which counterbalanced the MSZP-led government's power to some extent. Fidesz won 15 of 23 mayoralties in Hungary's largest cities—although its candidate narrowly lost the city of Budapest to a member of the Liberal Party—and majorities in 18 out of 20 regional assemblies.[21][22]

In the 2009 European Parliament election, Fidesz won a landslide victory, gaining 56.36% of the vote and 14 of Hungary's 22 seats. This predicted a landslide in the 2010 parliamentary elections, where they won the outright majority in the first round on 11 April, with the Fidesz-KDNP alliance winning 206 seats, including 119 individual seats. In the final result, they won 263 seats, of which 173 are individual seats.[23] Fidesz held 227 of these seats, giving it an outright majority in the National Assembly by itself.

After winning 53% of the popular vote in the first-round of the 2010 parliamentary election, which translated into a supermajority of 68% of parliamentary seats, giving Fidesz sufficient power to revise or replace the constitution, the party embarked on an extraordinary project of passing over 200 laws and drafting and adopting a new constitution—since followed by nearly 2000 amendments.

The new constitution has been widely criticized[24][25][26][27][28][29] by the Venice Commission for Democracy through Law,[30] the Council of Europe, the European Parliament[31] and the United States[32] for gathering too much power in the hands of the ruling party, Fidesz, for limiting oversight of the new constitution by the Constitutional Court of Hungary, and for removing democratic checks and balances in various areas, including the ordinary judiciary,[33] supervision of elections and the media.

In October 2013 Thorbjørn Jagland, Secretary General of the Council of Europe said that the Council were satisfied with the amendments which had been made to the criticised laws.[34]

Fidesz won the nationwide parliamentary election in April 2014 and secured a second supermajority with 133 seats (of 199) in the legislature. This supermajority was lost, however, when Tibor Navracsics was appointed to the European Commission. His Veszprém county seat was taken by an independent candidate in a by-election.[16] Another by-election on 12 April 2015 saw the supermajority lose a second seat, also in Veszprém, to a Jobbik candidate.[17]

Fidesz won the nationwide parliamentary election in April 2018 and secured a 3rd supermajority with 134 seats (of 199) in the legislature. Orbán and Fidesz campaigned primarily on the issues of immigration and foreign meddling, and the election was seen as a victory for right-wing populism in Europe.[35][36][37]

Leaders

| Image | Name | Entered office | Left office | Length of Leadership | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Viktor Orbán | 18 April 1993 | 29 January 2000 | 6 years, 286 days | Prime Minister, 1998–2002 |

| 2 | László Kövér | 29 January 2000 | 6 May 2001 | 1 year, 97 days | ||

| 3 | Zoltán Pokorni | 6 May 2001 | 3 July 2002 | 1 year, 58 days | ||

| 4 |  |

János Áder | 3 July 2002 | 17 May 2003 | 318 days | |

| 5 |  |

Viktor Orbán | 17 May 2003 | Incumbent | 15 years, 154 days | Prime Minister, 2010–present |

Ideology

Fidesz's position on the political spectrum has changed over time. At its inception as a student movement in the late-1980s, the party supported social and economic liberalism and European integration. As the Hungarian political landscape crystallized following the fall of communism and the first free elections, Fidesz began moving to the right. Although Fidesz was in opposition to the Hungarian Democratic Forum's national-conservative coalition government from 1990 to 1994, by 1998 Fidesz was the most prominent conservative political force in Hungary.

Fidesz is currently considered a national conservative party favoring interventionist policies on economic issues like handling of banks, and a strong conservative stance on social issues and European integration.[38][39][40] Like the Hungarian right in general, it has been more skeptical of the neoliberal economic policies than the Hungarian left: according to researchers, the elites of the Hungarian left (MSzP and SZDSZ) have been differentiated from the right by being more supportive of the classical liberal economic policies, while the right (especially extreme right) has advocated more interventionist policies. In contrast, on issues like church and state and family policies, the liberals show alignment along the traditional left-right spectrum.[41]

Fidesz has adopted anti-immigration stances and rhetoric.[42][43][44][45] Recently, the party has increasingly been described as far-right.[46][47][48][49][50]

The party is anti-communist.[51] In May 2018, the President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker attended and spoke at a celebration of the deceased Karl Marx’s 200th birthday, where he defended Marx's legacy. In response, MEPs from Fidesz wrote: "Marxist ideology led to the death of tens of millions and ruined the lives of hundreds of millions. The celebration of its founder is a mockery of their memory."[51]

Youth

In December 2005 the Congress of Fidesz established the Fidesz Youth Section as a division within the party gathering all members below the age of 30. The chairman of Fidesz Youth Section was Dániel Loppert until 2011. The current chairman is Áron Veress. The Fidesz Youth Section is member of European Democrat Students (EDS) and observer member in the Democrat Youth Community of Europe (DEMYC).

Electoral results

National Assembly

| Election | Votes | Seats | Rank | Government | Leader | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ±pp | # | +/− | ||||

| 1990 | 439,481 | 8.95% | – | 22 / 386 |

±0 | 5th | MDF–FKgP–KDNP | Viktor Orbán |

| MDF–EKGP–KDNP | ||||||||

| 1994 | 379,295 | 7.02% | 20 / 386 |

6th | MSZP–SZDSZ Supermajority | Viktor Orbán | ||

| 1998 | 1,263,522 | 28.18% | 148 / 386 |

1st | Fidesz-FKgP-MDF | Viktor Orbán | ||

| 20021 | 2,306,763 | 41.07% | 164 / 386 |

2nd | MSZP–SZDSZ | Viktor Orbán | ||

| 20062 | 2,272,979 | 42.03% | 141 / 386 |

2nd | MSZP–SZDSZ | Viktor Orbán | ||

| MSZP Minority | ||||||||

| 20102 | 2,706,292 | 52.73% | 227 / 386 |

1st | Fidesz–KDNP Supermajority | Viktor Orbán | ||

| 20142 | 2,264,486 | 44.87% | 117 / 199 |

1st | Fidesz–KDNP Supermajority | Viktor Orbán | ||

| 20182 | 2,824,206 | 49.27% | 117 / 199 |

1st | Fidesz–KDNP Supermajority | Viktor Orbán | ||

1 Joint list with Hungarian Democratic Forum (MDF)

2 Joint list with Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP)

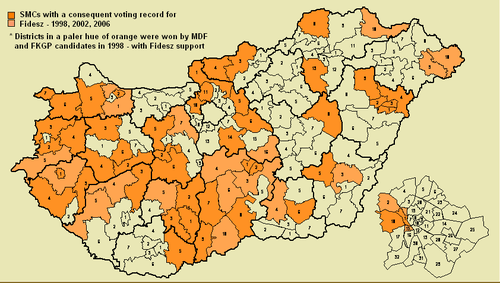

Single member constituencies voting consistently for Fidesz

The SMCs shown on the image have voted for Fidesz ever since 1998. SMCs with a paler hue of orange elected FKGP candidates in 1998, as part of a pact between the two parties.

In January 2010, László Kövér, head of the party's national board, told reporters the party was aiming at winning a two-thirds majority at the parliamentary elections in April. He noted that Fidesz had a realistic chance to win a landslide. Concerning the radical nationalist Jobbik party's gaining ground Kövér said it was a "lamentably negative" tendency, adding that it was rooted in the "disaster government" of the Socialist Party and its former liberal ally Free Democrats.[52]

European Parliament

| Election year | # of overall votes | % of overall vote | # of overall seats won | +/- | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 1,457,750 | 47.4% (1st) | 12 / 24 |

||

| 20091 | 1,632,309 | 56.36% (1st) | 13 / 22 |

||

| 20141 | 1,193,991 | 51.48% (1st) | 11 / 21 |

1 Joint list with Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP)

References

- ↑ {{cite book|page=379|publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press|first1=Tristan|last1=Mabry|first2=John|first3=Margaret|first4=Brendan|last4=O'Leary|last3=Moore|last2=McGarry|year=2013|title=Divided Nations and European Integration}}

- ↑ "Hungary experiences nationalism renaissance". Deutsche Welle. 1 June 2012.

- 1 2 Nordsieck, Wolfram (2018). "Hungary". Parties and Elections in Europe.

- 1 2 3 4 Hloušek, Vít; Kopeček, Lubomír (2010), Origin, Ideology and Transformation of Political Parties: East-Central and Western Europe Compared, Ashgate, p. 115

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bakke, Elisabeth (2010), "Central and East European party systems since 1989", Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989, Cambridge University Press, p. 79, ISBN 9781139487504, retrieved 17 November 2011

- ↑ "Orban drags Hungary through rapid change". Financial Times. 7 February 2011.

- ↑ "Territoriality and Eurosceptic Parties in V4 Countries" (PDF). Ispo.fss.muni.cz. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ {{cite web

Anti-immigration |url=http://www.policysolutions.hu/userfiles/elemzesek/Euroszkepticizmus%20Magyarorsz%C3%A1gon.pdf |format=PDF |title=Euroszkepticizmus Magyarországon |publisher=Policysolutions.hu |accessdate=2015-09-04 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150906103039/http://www.policysolutions.hu/userfiles/elemzesek/Euroszkepticizmus%20Magyarorsz%C3%A1gon.pdf |archivedate=2015-09-06 |df}} - 1 2 Hans-Jürgen Bieling (2015). "Uneven development and 'European crisis constitutionalism', or the reasons for and conditions of a 'passive revolution in trouble'". In Johannes Jäger; Elisabeth Springler. Asymmetric Crisis in Europe and Possible Futures: Critical Political Economy and Post-Keynesian Perspectives. Routledge. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-317-65298-4.

- ↑ "Hungary: the Fidesz Project" (PDF). Aspen Institute. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ↑ The Hungarian Patient: Social Opposition to an Illiberal Democracy. Central European University Press. 2015. p. 21.

- ↑ "Fidesz: The story so far", The Economist, 18 December 2010, retrieved 18 November 2011

- ↑ Right-wing Fidesz win election by landslide, Radio France Internationale, 12 April 2010, retrieved 18 November 2011

- ↑ Seres, Balint (12 April 2010), "Right-wing Fidesz party wins by landslide in Hungary elections", news.com.au, retrieved 18 November 2011

- ↑ Fidesz had common regional and nationwide lists and had common candidates with KDNP in the 2010 and 2014 elections

- 1 2 "Hungary's Ruling Party Loses Two-Thirds Majority after By-Election". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- 1 2 Dull, Szabolcs. "Győzött a Jobbik a tapolcai választáson". Index.hu. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ↑ Bayer, Lili (10 April 2018). "Orbán poised to tighten grip on power". Politico. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Archived October 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ (in Hungarian) Sólyom politikaformáló erő akar lenni, Kern Tamás, Index.hu, August 22, 2005

- ↑ "VoksCentrum - a választások univerzuma". Vokscentrum.hu. Archived from the original on 2007-08-18. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ↑ "Opposition makes substantial gains in Hungarian elections". Taipei Times. 2015-08-29. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Országos Választási Iroda - 2010 Országgyűlési Választások" (in Hungarian). Valasztas.hu. 2010-05-03. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ↑ Archived December 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Working Document 1" (PDF). Europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Working Document 2" (PDF). Europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Working Document 3" (PDF). Europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Working Document 4" (PDF). Europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Documents by opinions and studies". Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ↑ "EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) : OPINION" (PDF). Lapa.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Texts adopted - Tuesday, 5 July 2011 - Revised Hungarian constitution - P7_TA(2011)0315". Europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Remarks & Statements | Budapest, Hungary - Embassy of the United States". Hungary.usembassy.gov. 2011-12-08. Archived from the original on 2015-10-18. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ Archived March 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Ferenc Kumin — Council of Europe's Jagland: 'Hungarians Have Gone..." Ferenckumin.tumblr.com. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ↑ Than, Krisztina; Szakacs, Gergely (9 April 2018). "Hungary's Strongman Viktor Orban Wins Third Term in Power". Reuters. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Zalan, Eszter (9 April 2018). "Hungary's Orban in Sweeping Victory, Boosting EU Populists". EUobserver. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Murphy, Peter; Khera, Jastinder (9 April 2018). "Hungary's Orban Claims Victory as Nationalist Party Takes Sweeping Poll Lead". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ "Europe.view: Stars and soggy bottoms - The Economist". The Economist. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ↑ "Hegedűs Zsuzsa: Orbán igazi szociáldemokrata". Fent és lent - gátlástalan patriotizmus. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ↑ Archived May 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bodan Todosijević The Hungarian Voter: Left–Right Dimension as a Clue to Policy Preferences in International Political Science Review (2004), Vol 25, No. 4, p. 421

- ↑ "A Race To The Far Right In Hungarian Politics". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ↑ "Hungary set to reject EU refugee quotas in referendum". The Independent. 2016-10-02. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ↑ "Hungary's future: anti-immigration, anti-multiculturalism and anti-Roma?". openDemocracy. 2015-08-03. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ↑ Nolan, Daniel (2015-07-02). "Hungary government condemned over anti-immigration drive". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ↑ Schaeffer, Carol (28 May 2017). "How Hungary Became a Haven for the Alt-Right".

- ↑ Dunai, Marton. "Hungary's Orban courts far-right voters ahead of 2018 vote".

- ↑ "Hungary elections: Another populist test for Europe?". www.aljazeera.com.

- ↑ "Hungary gears up for election: what is at stake?".

- ↑ Huetlin, Josephine (7 April 2018). "In Hungary, Real News Has Become NSFW" – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- 1 2 "EU chief defends Marx in controversial speech to mark communist's birth". Yahoo News. 4 May 2018.

- ↑ MTI. "Opposition Fidesz aims at two-thirds majority". Politics.hu. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fidesz. |

- Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Union Official website

- Fidesz page on the website of the European People's Party

- Speech delivered by Mr Viktor Orban at the 17th Congress of Fidesz upon his election as president of Fidesz - Hungarian Civic Union, 17 May 2003 (from Google's cache)

- The History of FIDESZ (from Google's cache)

- Hungary's PM calls confidence vote