Fall of Kampala

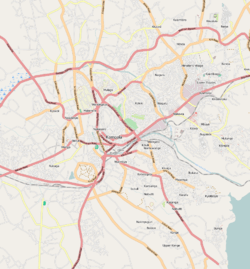

The Fall of Kampala, also known as the Liberation of Kampala, was a battle during the Uganda-Tanzania War, in which the combined forces of Tanzania and the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) attacked and captured the Ugandan capital, Kampala. As a result, Ugandan President Idi Amin was deposed, his forces were scattered, and a UNLF government was installed. Amin had seized power in Uganda in 1971 and established a brutal dictatorship. Seven years later he attempted to invade Tanzania to the south. Tanzania repulsed the assault and launched a counter-attack into Ugandan territory. Though Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere publicly claimed that he did not want to depose Amin, he suggested in private that the Ugandan dictator should be overthrown, and the government felt that Tanzania's security would be threatened unless Amin was removed from power. The Tanzanians originally hoped that anti-Amin forces led by the UNLF would seize the capital, but this was deemed infeasible after Liyan troops intervened in the war on Amin's behalf. Plans of attack were drawn up in late March, but the Tanzanians decided to attack Entebbe first after seeing a concentration of Ugandan and Libyan forces there. The Tanzanians routed the Libyans in the town and modified their offensive designs. The plans called for the 208th Brigade to advance from the south, spearheaded by Lieutenant Colonel Ben Msuya's 800-strong 19th Battalion, which was to secure the centre of Kampala. The 207th Brigade and a UNLF battalion were to attack from the west, while the 20st Brigade was to establish roadblocks in the north to prevent Ugandan units from withdrawing. An eastern corridor was left open to allow the Libyans, following their defeat in Entebbe, to withdraw to Jinja and fly out of the country. Amin prepared for the defence of Kampala but fled through the gap.

The Tanzanians began their assault on the city on the morning of 9 April. The 19th Battalion moved cautiously down the Entebbe-Kampala road. Other battalions of the 208th advanced on Port Bell. The 201st Brigade led by Brigadier established its roadblocks north of Kampala and intercepted both forces attempting to reinforce Kampala from Bombo and those attempting to effect a breakout. The 207th Brigade under Brigadier advanced from the west in tandem with the UNLF battalion, which secured Nateete and passed through Rubaga. One of the 207th's battalions seized Kasubi hill and the royal tomb of the Kabakas. The 19th Battalion encountered only sporadic resistance and was greeted by crowds of rejoicing civilians. Upon reaching Kampala's city centre, the unit, lacking in maps, had trouble navigating the streets. The Tanzanians secured the radio station and set up a command post on Kololo hill. The UNLF battalion occupied Republic House, the Ugandan army's headquarters at the edge of the city, unopposed, but was unable to take the State Research Bureau (Amin's secret police) at Nakasero. Men of the 207th and 208th Brigades seized the southern and western portions of the city. The few Libyan units in the area put up little resistance, most having retreated to Jinja.

By dawn of 10 April Tanzanian troops had cut off all routes leaving Kampala, including the road to Jinja, and began eliminating remaining pockets of resistance. Some UNLF forces conducted revenge killings against suspected collaborators with the Amin regime, while others attacked Kakwa and Nubians, both ethnic groups that had benefited from the dictatorship. Later in the morning Tanzanian artillery bombarded certain sectors of the city. More civilians, seeing that the troops on their streets were Tanzanian, came out from their dwellings to celebrate and loot. The remaining Ugandan soldiers in the city desperately attempted to escape by changing into civilian clothes and requisitioning civilian vehicles. Fighting continued into the next day. Casualty statistics are not exact, though Tanzanian losses are estimated to be light and dozens of Ugandan soldiers and civilians are believed to have died.

The battle marked the first time in the history of the continent that an African state seized the capital of another African country and deposed its government. In the following days civilians engaged in rampant looting, despite the attempts of Tanzanian and UNLF troops to maintain order. Immediately after the seizure of Kampala the Tanzanians began establishing a new Ugandan government. Though pro-Amin forces were left scattered and disjointed by the seizure of the capital, combat operations in the country continued until 3 June, when Tanzanian forces reached the Sudanese border and eliminated the last resistance.

Background

In 1971 Idi Amin launched a military coup that overthrew the President of Uganda, Milton Obote, precipitating a deterioration of relations with the neighboring state of Tanzania. Amin installed himself as President and ruled the country under a brutal dictatorship.[1] In October 1978 he launched an invasion of Tanzania.[2] Tanzania blunted the assault, unified anti-Amin opposition groups, and launched a counter-offensive.[3] The President of Tanzania, Julius Nyerere, told foreign diplomats that he did not intend to depose Amin, but only "teach him a lesson". The claim was not believed; Nyerere despised Amin, and he made statements to some of his colleagues about overthrowing him. The Tanzanian Government also felt that the northern border would not be secure unless the threat presented by Amin was eliminated.[4] After initial advances into Ugandan territory, Major General David Msuguri was appointed commander of the Tanzania People's Defence Force (TPDF)'s 20th Division and ordered to push further into the country.[5]

On 24 February 1979 the TPDF seized Masaka. Nyerere originally planned to halt his forces there and allow Ugandan exiles to attack Kampala, the Ugandan capital, and overthrow Amin. He feared that scenes of Tanzanian troops occupying the city would reflect poorly on the country's image abroad.[6] In late March the Ugandan opposition groups met in Moshi. They elected Yusuf Lule chairman of the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) and established a cabinet.[7] The next day President Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, an ally of Amin, attempted to stem the advance by sending an ultimatum to Nyerere, demanding that he withdraw his forces in 24 hours or face the opposition of Libyan troops (which were already present in Uganda). Nyerere rejected the threat in a radio broadcast, announcing that Libya's entry into the war did not change the Tanzanian government's view of Amin.[8] Ugandan rebel forces did not have the strength to defeat Libyan units, so Nyerere decided to use the TPDF to take Kampala.[6] Tanzanian leaders were also moved to capture the city after Ugandan planes bombed Kagera and following Amin's announcement that the inhabitants of Masaka and Mbarara would face retaliation for welcoming the Tanzanian invasion.[9] The successful formation of the UNLF government eased Tanzanian concerns about the aftermath of a seizure of the capital.[10] Plans of attack were drawn up on 31 March.[11]

Prelude

In early April Tanzanian forces began to concentrate their efforts on weakening the Ugandan position in Kampala.[12] Tanzanian commanders had originally assumed that Amin would station the bulk of his forces in the capital, and their initial plans called for a direct attack on the city. But from the high ground in Mpigi they could see the Entebbe peninsula, where there was a heavy amount of Libyan air traffic and a large contingent of Ugandan and Libyan soldiers. If the TPDF seized Kampala before securing the town of Entebbe, it would susceptible to a flanking attack.[10] Taking Entebbe would cutoff Uganda's Libyan reinforcements and permit an assault on the capital from the south.[13] Msuguri made the decision to attack the peninsula first, and ordered the 208th Brigade to secure it. A preliminary bombardment frightened Amin in his official residence, the Entebbe State House, and he fled via helicopter to Kampala. On 7 April the brigade advanced into the town. Many Libyan soldiers attempted to evacuate to Kampala but were unsuccessful.[14] Following the seizure of the Entebbe, the remnants of the Libyan force and the Ugandan Army took up positions around Kampala. Their morale was extremely low.[15]

On the morning of 8 April Tanzanian officers held a final meeting in the Entebbe State House before the attack on Kampala. Brigadier Mwita Marwa, commander of the 208th Brigade, conducted the briefing. Nyerere requested that his commanders leave the eastern road from the city leading to Jinja be left clear so Libyan troops and foreign diplomats could evacuate. He thought that by allowing the former to escape, Libya could quietly safe face and withdraw from the war. Nyerere also feared that further conflict with Libyan troops would incite Afro-Arab tensions and invite the armed belligerence of Arab states. He sent a message to Gaddafi explaining his decision, saying that the Libyans could be airlifted out of Uganda unopposed from the airstrip in Jinja.[16] He further requested that his forces avoid damaging key buildings in the city, including Mulago Hospital, Makerere University, and Parliament.[11] The Tanzanian plan of attack called for an advance by the 207th Brigade and a UNLF battalion from the west along the road from Masaka with a simultaneous assault from Entebbe in the south by the 208th Brigade. The latter's 19th Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Ben Msuya was earmarked for the seizure of the city center, while other units were to cover their flanks in the bush. The 201st Brigade was to maintain a "blocking action" north of Kampala to prevent Ugandan forces from escaping.[16]

A week before the Tanzanian attack Amin ordered all soldiers in the Kampala garrison to evacuate their families.[9] He made final preparations for the defence of the capital,[17] and General Dusman Sabuni was left in charge of the defences.[18] Journalists estimated that Amin had 2,000 to 3,000 soldiers garrisoning the city. Many civilians also fled in anticipation of a battle, though Minister of Commerce Muhammad Bakhit declared that they had to return within two days or have their property "reallocated".[19] On 8 April the Soviet Union's diplomats evacuated in a convoy accompanied by the personnel of other Eastern bloc legations.[20]

The 800-strong 19th Battalion entrenched itself on a hill 21 kilometers away from Kampala overlooking the road from Entebbe.[17] Throughout the night of 8 April the battalion command post faced harassing fire from a tank. Ugandan reconnaissance patrols engaged in sporadic fighting with Tanzanian defences.[21] Artillery bombarded Kampala's suburbs.[22] At 03:30 on 9 April the 19th Battalion descended from its position. TPDF soon thereafter artillery initiated a 15-minute bombardment of Ugandan positions near around Kampala. The battalion reassembled on the Entebbe-Kampala road and began its advance. Two companies advanced parallel down either side of the road in the bush to screen for ambushes.[23] The rest of the battalion split into companies that walked on the alternating dirt shoulders of the road. They occasionally paused to ensure the advance units stayed ahead. At 09:00 the battalion, having covered the distance necessitated by the battle plan, re-encamped itself around a residence along the side of the road.[18]

Battle

9 April

Later in the morning of 9 April Tanzanian forces were ordered to seize Kampala. The 19th Battalion vacated its position and assembled on the Entebbe-Kampala road. Other battalions of the 208th secured Cape Town View, Amin's villa on Lake Victoria, and advanced on Port Bell. The 201st Brigade led by Brigadier Imran Kombe established roadblocks north of Kampala and intercepted both forces attempting to reinforce Kampala from Bombo and those attempting to effect a breakout. Over the course of the day they destroyed seven vehicles and killed 80 Ugandan soldiers. The 207th Brigade under Brigadier John Walden advanced from the west in tandem with a UNLF battalion under Lieutenant Colonel David Oyite Ojok. Ojok's men secured Nateete and passed through Rubaga. One of the 207th's battalions seized Kasubi hill and the royal tomb of the Kabakas.[24]

As the 19th Battalion advanced down the Entebbe-Kampala road, it was joined by an increasing amount of celebratory civilians, eager for the removal of the Amin regime. The column did not encounter resistance until it came under small-arms fire near the Makindye roundabout from a marketplace by the left side of the road, about two kilometers from the center of the city. The Tanzanian troops took cover in a drainage ditch and returned fire while the civilians scattered.[25] Fire was exchanged for 10 minutes until the source of the opposition, a limousine occupied by five Ugandan soldiers armed with semi-automatic weapons, emerged from cover and drove towards the Tanzanian column. It was quickly destroyed with small-arms fire, a rocket-propelled grenade, and a 75mm tank shell. The Tanzanians searched the market but found no more Ugandans, and subsequently resumed their march into the capital, joined by the cheering civilians. The battalion received some harassing fire but took no casualties and proceeded to the clock tower in Kampala where the Entebbe road entered the downtown, which was reached at 17:00.[26]

Lieutenant Colonel Msuya was eager to complete his battalion's objectives before nightfall in two hours. His decisions were complicated by the fact that he had no map of Kampala and had to rely upon a Ugandan guide for directions. He resolved to secure the radio station first. Leaving a guard behind to prevent the civilians from following, the battalion moved out into in city streets but with only the guide's confused and limited directions, its progress was slow.[27] Aside from a brief firefight with Ugandan soldiers positioned in a balcony, the 19th Battalion located the radio station without incident. Though its equipment was intact, Msuya was under orders not to make any broadcasts (He told a junior officer, "This is almost worth getting court-martialed for.").[28] The Tanzanians repulsed a brief ambush from an adjacent skyscraper before considering their next move. They were supposed to secure Nakasero hill, the location of the State Research Bureau and the presidential residence, and Kololo hill, home to Amin's personal "Command Post", before nightfall. Msuya determined that only one area could be seized in the time frame, and of the two choices Kololo presented a safer location for an overnight encampment.[29] Meanwhile the UNLF battalion occupied Republic House, the Ugandan army's headquarters at the edge of the city. They were unopposed, but five men were killed by friendly fire when Tanzanian artillery bombarded the location, the gunners unaware that the location had been taken. At around nightfall the UNLF force approached the State Research Bureau at Nakasero in the belief that it had been abandoned. When the unit was close, Ugandan soldiers opened fire, destroying a Land Rover and forcing the UNLF to retreat.[30] The Ugandans later abandoned the Bureau, but threw grenades into the holding cells in an attempt to kill the last prisoners.[31]

While the bulk of the 19th Battalion set out for Kololo, a detached company set up an ambush position in a park overlooking a street that led towards the Jinja road. The Tanzanians attacked two passing Ugandan Land Rovers, killing their three occupants. In one of the vehicles the soldiers recovered a detailed plan for Kampala's defense, with various sectors responsible to certain battalions and commanders, most of which had already dispersed.[32] By nightfall the 19th Battalion had not located the Command Post. Kampala was quiet and there was no electricity in the entire city. Eventually the Ugandan guide directed the unit to a golf course which the troops cut across to the base of Kololo. By 21:00 the Tanzanians were following residential streets up the hill.[33] Frustrated by his guide's inability to locate the Command Post, Msuya decided to forgo the location and establish his own in an abandoned home whilst his battalion dug trenches and established roadblocks. At 23:00 he held a toast with his officers to celebrate the capture of Kampala.[32]

Over night several other battalions of the 208th moved into the southern portion of Kampala, while the 207th occupied the west.[20] The few Libyan units in the city put up little resistance. Most retreated to Jinja and then to Ethiopia and Kenya to await repatriation.[15] The UNLF battalion established its camp in the golf course. As the troops were settling down a small white car drove by and an occupant opened fire, mortally wounding an officer. The UNLF subsequently erected roadblocks around the location. The men maintaining them grew drunk throughout the night on pillaged beer and whisky. At 04:00 on 10 April the East German ambassador, Gottfried Lessing, and his wife left their residence in a small white car with another vehicle following in an attempt to escape the city. When they drove by the golf course two rocket-propelled grenades were fired, destroying the cars and killing the four occupants.[30]

10 April

By dawn of 10 April Tanzanian troops had cut off all routes leaving Kampala, including the road to Jinja, and began eliminating the remaining pockets of resistance.[20] Some UNLF forces conducted revenge killings against suspected collaborators with the Amin regime, while others attacked Kakwa and Nubians, both ethnic groups that had benefited from the dictatorship.[31] Later in the morning Tanzanian artillery bombarded certain sectors of the city. More civilians, seeing that the troops on their streets were Tanzanian, came out from their dwellings to celebrate and loot. Meanwhile, the diplomatic staff resident on Kololo hill felt it was safe enough to begin visiting Msuya's command post to pay their respects to him.[34] Civilians raided the files of the State Research Bureau in search of records that contained the whereabouts of missing family members.[31] The Tanzanians found among the documents a copy of their top-secret plan of attack for Kampala.[35] Lieutenant Colonel Salim Hassan Boma led a detachment on a security sweep. On the edge of the city they discovered Luzira Prison. Boma ordered over 1,700 inmates held to be set free.[36]

The remaining Ugandan soldiers in the city desperately attempted to escape by changing into civilian clothes and requisitioning civilian vehicles. They robbed residents at gunpoint and in some cases murdered them to secure the items. As Tanzanian patrols secured Kampala's neighborhoods, some of them stumbled across the Ugandan soldiers and exchanged fire with them. Three men attempted to rob the residence of the First Secretary of the French Embassy, but were driven away by gunfire from the secretary's wife.[37] At least 10 Ugandan soldiers were beaten to death by enraged civilians.[1] Amin fled to Jinja, though how and precisely when are not agreed upon.[lower-alpha 1]

11 April

On 11 April Lieutenant Colonel Juma Butabika, one of Amin's top commanders, was killed in a firefight with soldiers of the 205th and 208th Brigades in the Bwaise-Kawempe area as they attempted to secure the northern section of the city.[11] That day, shortly before the fall of the city was announced, Amin held a meeting with his advisers in Munyonyo, where it was agreed that they should flee into exile. They drove east before boarding an aircraft and flying to Iraq.[41]

Aftermath

Statistics for battle casualties were unclear in the immediate aftermath of the battle. According to journalist Martha Honey, fewer than 100 Ugandan soldiers were killed.[1] The Superintendent of Mortuaries supervised the collection of bodies, and by 15 April he had recovered over 200 dead Ugandan soldiers and civilians. He estimated that the total statistic could be as high as 500.[42] According to the Daily Monitor, up to several dozen Ugandan civilians were killed. Over 500 Ugandan soldiers were captured by the TPDF.[11] Sabuni was arrested by the UNLF and charged with murder He later died from undernourishment.[43] The Libyans suffered few casualties during the battle,[15] though large stocks of Libyan munitions were seized.[44] The TPDF casualties were also deemed to be light; only three members of the 19th Battalion were wounded in the fighting.[1]

The Tanzanians recovered the body of Hans Poppe, a biracial police officer who had been killed in a 1971 border clash. His corpse had been put on display by Amin as evidence that foreign mercenaries were being deployed against him. The body was repatriated and buried.[45] Immediately after the seizure of Kampala the TPDF began establishing a new Ugandan government. On 13 April Lule was flown into the city and installed as President of Uganda. Though pro-Amin forces were left scattered and disjointed by the seizure of the capital, combat operations in the country continued until 3 June, when Tanzanian forces reached the Sudanese border and eliminated the last resistance.[38] In the following days civilians engaged in rampant looting, despite the attempts of Tanzanian and UNLF troops to maintain order.[46] The TPDF withdrew from Ugandan in mid-1981.[47]

Legacy

The fall of Kampala marked the first time in the history of the continent that an African state seized the capital of another African country.[48] The overthrow of a sovereign head of state by a foreign military had never occurred in Africa and had been strongly discouraged by the Organisation of African Unity. The invasion and removal of Amin was controversial, though most Western and African states tacitly accepted the action. The New York Times wrote, "Tanzania has set a disturbing precedent. What has been done this time in a good cause, and with considerable provocation, might as easily be done by others in [different] circumstances." According to Roy May and Oliver Furley, "It marked a mile-post in the history of Africa."[49]

Notes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Honey, Martha (12 April 1979). "Ugandan Capital Captured". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Honey, Martha (5 April 1979). "Anti-Amin Troops Enter Kampala". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "1979: New president for war-torn Uganda". BBC On This Day. British Broadcasting Company. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ Anderson & Rolandsen 2017, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 79.

- 1 2 Anderson & Rolandsen 2017, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 117.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 120.

- 1 2 Lubega, Henry (11 April 2018). "39 years after war that brought down Amin". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 4 "How Mbarara, Kampala fell to Tanzanian army". Daily Monitor. 27 April 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Pollack 2004, p. 372.

- ↑ Pollack 2004, pp. 372–373.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 121–122.

- 1 2 3 Pollack 2004, p. 373.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 124–125.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 125.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 130.

- ↑ Darnton, John (10 April 1979). "Amin's Forces Appear to Fight Harder". The New York Times. p. A1.

- 1 2 3 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 145.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 126.

- ↑ "Shelling Gives Kampala its "First Real Night of War"". The New York Times. 9 April 1979. p. A3.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 134.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 135.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 137–138.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 149.

- 1 2 Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 138.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 143.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 150.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 151.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 148–149.

- 1 2 Anderson & Rolandsen 2017, p. 163.

- ↑ Strasser, Steven; Gibson, Helen; Moreau, Ron (23 April 1979). "The Fall of Idi Amin". Newsweek. p. 41.

- ↑ Mugabe, Faustin (8 May 2016). "How Amin escaped from Kampala". Daily Monitor. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ↑ Magembe, Muwonge (18 August 2015). "Aspects of Amin's life that you missed". New Vision. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ Winfrey, Carey (16 April 1979). "Death Toll in Uganda Increases in Wake of Battle for Kampala". The New York Times. pp. A1, A8.

- ↑ Uganda 1981, p. 77.

- ↑ Pollack 2004, p. 375.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 35.

- ↑ Honey, Martha (12 April 1979). "Ugandans go on a looting spree". The Guardian.

- ↑ Cowell, Alan (10 July 1981). "Tanzanian Withdrawal Leaves Kampala Jumpy". The New York Times. p. A2.

- ↑ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 124.

- ↑ May & Furley 2017, The Verdict on Tanzania: International Relations.

References

- "Uganda". African Defence Journal. Paris: Société africaine de presse et d'édition fusionnées (5–16). 1981. ISSN 0244-0342.

- Anderson, David M.; Rolandsen, Øystein H., eds. (2017). Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa: The Struggles of Emerging States. Routledge. ISBN 9781317539520.

- Avirgan, Tony; Honey, Martha (1983). War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Tanzania Publishing House. ISBN 9789976100563.

- May, Roy; Furley, Oliver (2017). African Interventionist States. Routledge. ISBN 9781351756358.

- Pollack, Kenneth Michael (2004). Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948-1991. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803206861.