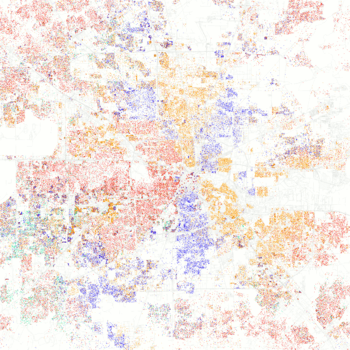

Ethnic groups in Houston

Houston is a diverse and international city, in part because of its many academic institutions and strong biomedical, energy, manufacturing and aerospace industries. According to the U.S. Census 2000, the racial makeup of the city was 49.3% White (including Hispanic or Latino), 25.3% Black or African American, 0.4% Native American, 5.3% Asian, 0.1&% Pacific Islander, 16.5% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. 37% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race.

By 2010 Houston had significant numbers of Hispanic and Latino Americans, Chinese Americans, and Indian Americans, as well as the second-largest Vietnamese-American population of any U.S. city. Houston became a "majority-minority" city (one where the non-Hispanic White population is smaller than the minority groups combined) in the 1990s, and by 2000 Greater Houston became majority-minority.[1] John B. Strait and Gang Gong, authors of the article "Ethnic Diversity in Houston, Texas: The Evolution of Residential Segregation in the Bayou City, 1990–2000," wrote that in the 1990s, the minority groups of Houston became more integrated with one another but more segregated from whites. Hispanics integrated with other groups more because the overall number of Hispanics in Greater Houston increased. Many Asians moved into neighborhoods with other Asians, and blacks and Hispanics moved into neighborhoods which Whites were leaving.[2]

The Daily Mail stated, in regards to the 2000 census data, that the racial and ethnic diversity in Houston and Greater Houston increases further from the center of the city.[3]

Hispanics and Latinos

The Hispanic population in Houston is increasing as more immigrants from Latin American countries come to work in the area. As of 2006 the city has the third-largest Hispanic population in the United States. As of the same year Karl Eschbach, a University of Texas Medical Branch demographer, said that the number of illegal aliens in the Houston area was estimated at about 400,000, with over 70% being of Mexican descent.[4] This influx of immigrants is partially responsible for Houston having a population younger than the national average.

As of 2011, the city is 44% Hispanic. As of 2011, of the city's U.S. citizens that are Hispanic, half are at voting age or older. Many Hispanics in Houston are not U.S. citizens, especially those living in Gulfton and Spring Branch. As a result, Hispanics have proportionally less representation in the municipal government than other ethnic groups. As of April 2011 two of the Houston City Council members are Hispanic, making up 18% of the council.[5]

As of 2010, Strait and Gong, authors of "Ethnic Diversity in Houston, Texas: The Evolution of Residential Segregation in the Bayou City, 1990–2000," stated that Hispanics and Latinos had "intermediate levels of segregation" from non-Hispanic whites.[6]

In the early 1980s, there were 300,000 native Hispanics, and an estimated 80,000 illegal immigrants from Mexico in Houston.[7]

In 1985, Harris County had about 500,000 Hispanics. Eschbach said that, historically, Hispanics resided in specific neighborhoods of Houston, such as Denver Harbor, the Houston Heights, Magnolia Park, and the Northside. Between 1985 and 2005, the county's Hispanic population tripled, with Hispanics making up about 40% of the county's residents. In most communities inside and outside Beltway 8, Hispanics became the predominant ethnic group. Some communities in Greater Houston which do not have Hispanics as the predominant ethnic group include expensive, predominantly non-Hispanic white communities such as Memorial, Uptown, and West University Place; and historically African-American neighborhoods located south and northeast of Downtown Houston. Eschbach said, "But even these core black and white neighborhoods are experiencing Hispanic inroads. Today, Hispanics live everywhere."[8]

Asians

Houston also has large populations of immigrants from Asia. In addition, the city has the largest Vietnamese American population in Texas and third-largest in the United States as of 2004.[9][10]

In 1910 30 Asians lived in Houston. 20 were Japanese and 10 were Chinese.[11] The Chinese were the only ethnic group with a significant settlement pattern in Houston until the 1970s. The lack of Asian immigration in Greater Houston was due to historical restrictions on Asian Americans. According to the 1980 U.S. census, 484 Chinese immigrants currently living in the area had lived there prior to 1950, of twelve Asian nationalities other than Chinese listed by the census for the Houston area, there were fewer than 100 immigrants who had settled before 1950. The 1965 Immigration Act, which had ended the restrictions, allowed an increase in Chinese Americans. Chinese residents. The number increased to 121 by the start of World War II. During the war, many Chinese from southern states migrated to take advantage of the economy and the population increased by more than twice its size.[12]

In the 1970s large-scale Asian immigration to Houston began. In 1980 48,000 Asians lived in Greater Houston. The amount of Asian immigration increased in the 1980s. In 1990 90,000 Asian immigrants lived in Harris County, and 48,000 Asians lived in Greater Houston.[13] As of 1990 the largest two Asian immigrant groups to Houston were the Chinese and the Vietnamese,[14] making up 46% of all Asian immigrants,[15] with 15,568 Vietnamese and 10,817 of Chinese from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The others were 7,044 Indians, 4,807 Filipinos, 3,249 Koreans, 2,419 Iranians, 2,411 Pakistanis, 1,950 Japanese, 1,489 Lebanese, and 1,146 Cambodians.[13]

In the 1990s the Asian immigration rates exceeded those of Hispanics. A U.S. Census survey conducted in 1997 stated that in Harris County and Fort Bend County, there were 202,685 Asians combined.[13] In 1998 Betty Ann Bowser, a reporter for PBS Newshour, said that many Southeast Asians came to Houston because "its hot humid climate reminded them of home."[16]

According to a 2002 survey of 500 Asian Americans in Harris County overseen by Stephen Klineberg, a professor at Rice University, Asian immigrants have substantially lower household income than Anglo residents and other immigrant groups, while they have higher levels of education.[17]

In 2007 Houston had 16,000 Asian American businesses. A 2006 U.S. Census Bureau report stated that the annual revenues of those businesses totaled to $5.5 billion ($6676625949.16 in today's money).[18]

In 2010 Strait and Gong stated that Asians were "only modestly segregated from" non-Hispanic whites.[6]

Vietnamese

In 2005 Greater Houston had 32,000 Vietnamese and Vietnamese Americans, making it the second largest Vietnamese American community in the United States after that of San Jose, California.[19]

Chinese

According to the American Community Survey, as of 2013, Greater Houston (Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown metropolitan area) has 72,320 residents of Chinese origin.[20]

South Asians

As of the 2010 U.S. Census, if the Indian American and Pakistani American populations are combined, there are 50,045 of them in Harris County, together making up 17.9% of the Asians in Harris County and being the second largest Asian ethnic group in Harris County. The combined group was the largest Asian ethnic group in Fort Bend County, making up 31% of the Asians there, and the largest Asian ethnic group in Montgomery County.[21]

In 1983 Allison Cook of the Texas Monthly stated that "Some estimates put the number of Indians and Pakistanis in Houston as high as 25,000."[22]

In 1990 there were a combined 21,191 Indian and Pakistani descent people in Harris County, making up 19.3% of the county's Asians and at the time being the third largest Asian ethnic group. In 2000 there were 35,971 members of the combined group in Harris County, making up 18.6% of the county's Asians and now being the second largest Asian ethnic group in the county. From 2000 to 2010 the combined group in Harris County increased by 39%.[21]

Half a dozen Indian American and Pakistani American newspapers are offered in stores and restaurants. The publications include India Herald and the Voice of Asia. The city has Masala Radio, a South Asian radio station. Indian singers often make tour stops in Houston. The Bollywood 6 movie theater on Texas State Highway 6 plays Indian films. The Houston area has Indian dance schools, including the Abhinaya School of Performing Arts and the Shri Natraj School of Dance.[23]

Of the Zoroastrian groups in Houston, As of 2000, Parsi were one of the two main Zoroastrian groups. As of that year the total number of Iranians of all religions in Houston is, on a 10 to 1 basis, larger than the total Parsi population.[24] As of 2000 the Zoroastrian Association of Houston (ZAH) is majority Parsi. Rustomji wrote that because of that and the historic tensions between the Parsi and Iranian groups, the Iranians in Houston did not become full members of the ZAH. Rustomji stated that Iranian Zoroastrians "attend religious functions sporadically and remain tentative about their ability to fully integrate, culturally and religiously, with Parsis."[24]

Asian Indians

Harris County had almost 36,000 Indian Americans as of the 2000 Census. The population had a $53,000 ($75316.33 in today's money) median yearly household income, $11,000 ($15631.69 in today's money) more than the county average. Almost 65% of the Indian Americans in Harris County had university and college degrees, compared to 18% of all of the Harris County population. Indian Americans in Fort Bend County, as of the same census, numbered at almost 13,000 and had a median annual income of $84,000 ($119369.28 in today's money). 62% of Indian Americans in Fort Bend County had university and college degrees, compared to 25% of all residents of Fort Bend County. An estimate from the 2009 American Community Survey stated that Harris County had 46,125 Indian Americans and that Fort Bend County had 25,104 Indian Americans. Katharine Shilcutt of the Houston Press said that the high education and income levels of Indian Americans caused businesses in the Mahatma Gandhi District, an Indian American ethnic enclave in Houston, to thrive.[25]

In 1999 the Houston area had about 500 Indian Catholics. There were no particular Indian Catholic churches.[26]

As of 2007, the median income of Indians in Houston was $50,250.[27]

As of 2012 the majority of the city's Sikhs originate from the portion of Punjab in India.[28]

As of 2007 there were over 24 Indian-American-oriented publications. As of that year, most Indian-American newspapers in Houston are in English. Some smaller newspapers are in Indian languages such as Hindi and Gujarati.[27]

The Indo-American News, a newspaper owned by K.L. Sindwani, is distributed to fifty locations in Southwest Houston and has a 5,000 copy-per-week print rate. As of 2007 each issue has 44 pages. Sindwani established it in 1982; at the time he was the only employee and the each issue had eight pages.[27]

The self-published novel An Indian in Cowboy Country was written by Indian immigrant Pradeep Anand, who works as an engineer and lives in Sugar Land.[29]

Pakistanis

In 2007 the Pakistani-American Association of Greater Houston (PAGH) stated that about 60,000 people of Pakistani origin lived in Greater Houston and that many of them lived in Southwest Houston.[30] As of 2000, over 70% of the Muslims in Houston are Indian or Pakistani.[31]

Bangladeshis

The Bangladesh Association, Houston (BAH, Bengali: বাংলাদেশ এসোসিয়েশন, হিউস্টন[32]),[33] Bangladesh Students Association at the University of Houston, and Bangladesh Society of Greater Houston are the Bangladeshi groups in the city.

In 1971 the Bangladeshi American community in Greater Houston consisted of about 10 university students; 1971 was the year when Bangladesh seceded from Pakistan. As of 2011 the Bangladeshi American population of Greater Houston includes over 10,000 people. The Bangladesh Association bought 4 acres (1.6 ha) of land in southwestern unincorporated Harris County in 2001. By 2011 the association announced plans to develop the $2.5 million ($2719674.56 in today's money) facility Bangladeshi American Center, which will include auditoriums, classrooms, a playground, and an outdoor sports complex. .[34] The first donor conference was held at the Stafford Civic Center in Stafford.In 2012, Bangladeshi Students Association at the University of Houston was resurrected after a ten-year hiatus. This organization was first formed in the 70's soon after the independence of Bangladesh in 1971. UH BSA serves as the link between the 2nd generation of Bangladeshis and the older generation[35]

Filipinos

As of the 2010 U.S. Census there were 22,575 ethnic Filipinos in Harris County, making up 8.1% of the county's Asian population. In 1990 there were 10,502 ethnic Filipinos in the county, making up 9.6% of the county's Asian population. In 2000 this had increased to 15,576, making up 8.1% of the county's Asian population. The Filipino population increased by 45% from 2000 to 2010.[21]

In 1999 the Houston area had about 40,000 Filipino Catholics. There were no particular Filipino Catholic churches.[26]

Koreans

As of 1983 there were about 10,000 Korean people in Houston.[36]

As of the 2010 U.S. Census there were 11,813 ethnic Koreans in Harris County, making up 4.2% of the county's Asian population. In 1990 there were 6,571 ethnic Koreans, making up 6% of the county's Asian population. In 2000 this figure had increased to 8,764, making up 4.5% of the county's Asian population. The number of Koreans increased by 35% from 2000 to 2010.[21]

Spring Branch has a large ethnic Korean population.[37]

In 1999 the Houston area had over 1,000 Korean Catholics. The Korean Catholic church is St. Andrew Kim Catholic Church in Spring Branch, named after Andrew Kim Taegon.[26]

Japanese

As of the 2010 U.S. Census, there were 3,566 people of Japanese descent in Harris County, making up 1.3% of the Asians in the county. In 1990 there were 3,425 ethnic Japanese in the county, making up 3.1% of the county's Asians, and in 2000 there were 3,574 ethnic Japanese in the county, making up 1.9% of the county's Asians.[21]

Cambodians

The first Cambodians arrived in Houston while fleeing the Cambodian genocide. A woman named Yani Rose Keo became a community leader and was involved in the affairs of Cambodians who settled in Houston. In 2000 Yani Keo stated that 80,000 people of Cambodian origins lived in Houston while Greater Houston had a total of 82,000 people of Cambodian origins.[38] Many Cambodians in Houston operate doughnut shops; according to Samoeurn Phan, a Cambodian man quoted by food writer Robb Walsh in the Washington Post, about 90% of the doughnut shops in Houston were owned by Cambodians in 2017.[39]

In 1985 Keo established a farm in an area called "Little Cambodia",[40] in Brazoria County, near Rosharon. Terrence McCoy of the Houston Press stated that there were "perhaps" 90 families of Cambodian origin living there.[41] In the 2000s (decade) the farmers got into a dispute with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) over the farming of water spinach, which the TPWD classified as “Harmful or Potentially Harmful Exotic Fish, Shellfish and Aquatic Plants.”[42] Ultimately the TPWD allowed the farming of water spinach. "Little Cambodia" sustained damage during Hurricane Ike in 2008,[41] and in Hurricane Harvey in 2017.[40]

Other Asian ethnic groups

In addition Houston has populations of Asians from other countries in Southeast Asia and East Asia. This includes Burma (Myanmar), Indonesia, and Thailand. In 2010 there were 40,684 Asians from Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Thailand living in Harris County, making up 14.5% of the Asians there.[21]

In 1990 there were 12,114 Asians from other countries in Harris County, making up 11% of the county's Asian population. In 2000 the number had increased to 20,579, making up 10.7% of the county's Asian population. The other Asian population of Harris County increased by almost 100% from 2000 to 2010.[21]

As of 1983 the Consulate-General of Indonesia, Houston estimated that 300 Indonesian persons were in Houston.[43] As of 2004 Houston had the fifth largest Indonesian population in the United States; this helps sustain the consulate.[44]

Over the three years leading to 2009, Houston took about 2,200 Burmese.[45]

Blacks

African Americans

Historically Houston had a significant African-American population,[11] as this area of the state developed cotton plantation agriculture that was dependent on enslaved laborers. Thousands of enslaved African-Americans lived near the city before the Civil War. Many of them worked on sugar and cotton plantations. Slaves held in the city primarily worked in domestic household and artisan jobs. In 1860 forty-nine percent of the city's population was made up of enslaved people of color. In 1860 nearby Fort Bend County had a population with twice as many black slaves as white residents; it was one of six majority-black counties statewide.

From the 1870s to the 1890s, black people made up almost 40% of Houston's population.[11] Before being effectively disfranchised by the state legislature imposing payment of a poll tax in 1902, they were politically active and strongly supported Republican Party candidates.[11] After disfranchisement, the state legislature established legal segregation and Jim Crow. Between 1910 and 1970, the black population of Houston ranged from 21% to 32.7%.[11] They were virtually without political representation until after 1965 and passage of the federal Voting Rights Act, which enforced their constitutional rights of suffrage. Many blacks left Houston for the West Coast during and after World War II in the Great Migration, as jobs increased rapidly in the defense industry on that coast and social conditions were better.

In 1970, 90% of the black people in Houston lived in predominantly African-American neighborhoods, reflecting decades of legal, residential segregation. By 1980 there was some increase in diversity in the city, and 82% of blacks lived in majority-black areas.[46] Since the late 20th century, with changes in social conditions and the burgeoning Houston economy, there has been a New Great Migration of blacks to the South. Many are college educated and have moved to Houston for its lower cost of living and job opportunities compared to some northern and western cities.[47] Many of the new professional migrants settle directly in the suburbs, which offer more housing than the city; among them are upper class, majority-black neighborhoods.

In 2010 Strait and Gong stated that of all ethnic groups in Houston, African Americans were the most segregated from non-Hispanic whites.[6]

African immigrants

A significant number of African immigrants have made the Houston area home.[48] As of 2003 Houston does not have as many African immigrants as Hispanic and Asian immigrants. The African immigrants in Houston have higher education levels than other immigrant groups and US-born whites. According to Stephen Klineberg, a sociology professor at Rice University, as of 2003, almost 35% of African immigrants have university degrees, and 28% of African immigrants have postgraduate degrees. In the Houston area, 28% of US-born Whites have university degrees, and 16% have postgraduate degrees.[49] In 2012, the total trade between Houston and Africa was $19.7 billion. Houston is Africa's largest U.S. trade partner.[50]

Nigerians

Charles W. Corey of the U.S. Department of State said that it has been estimated that Greater Houston has the largest Nigerian expatriate population in the United States. [48] As of 2014 an estimated 150,000 Nigerian Americans live in Houston.[51] As of 2003 Houston has 23,000 Nigerian Americans. Many Nigerian Americans choose Houston over other American destinations due to its warmer climate and the ease of establishing businesses.[49] Nigerians in Houston are highly educated and often have postgraduate degrees.[52] Nigerians in the Houston area opened Nigerian groceries, restaurants, and churches.[53]

Until Continental Airlines began nonstop flights to Lagos from George Bush Intercontinental Airport in November 2011, many Nigerians had to fly through Europe to travel between Texas and Nigeria.[54] Jenalia Moreno of the Houston Chronicle said that the Nigerian community and the energy companies in Houston have worked for a long time to get a flight to Nigeria from this city.[55] In 2016 United Airlines, which had merged with Continental, canceled the Lagos route, citing a decline in the energy industry and inability to get currency out of Nigeria.[56]

Ethiopians

Mesfin Genanaw, a Houston Community College teacher who was one of the individuals who assisted with the building of the area Ethiopian Orthodox church, stated in a 2003 Houston Chronicle article that there are an estimated 5,000 Ethiopians in Greater Houston.[57]

One Ethiopian Orthodox church in Houston is the Debre Selam Medhanealem Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahdo Church (Amharic: ደብረ ሰላም መድኃኔዓለም የኢትዮጵያ ኦርቶዶክስ ተዋሕዶ ቤተ ክርስቲያን Debre Selam MedhaneAlem YeItyopphya Ortodoks Tewahedo Bete Kristiyan; the name approximately means "Sanctuary of Peace and the Savior"). Prior to the construction of the church, those of the Ethiopian Orthodox faith worshiped at Coptic Orthodox churches. Genanaw, stated that in 1992 20 Ethiopian women who were attending a Coptic church planned the establishment of an Ethiopian church. In 1993 the group purchased a 2.5-acre (1.0 ha) site and a tent, and conducted church services in a tent. After fundraisers were held, in 1995 construction of the permanent church started, and the church later obtained an additional 5 acres (2.0 ha) of land.[57]

Non-Hispanic Whites

White Americans of northern and western European origin, particularly those of German and British origins, founded the City of Houston. Roberto R. Treviño, author of The Church in the Barrio: Mexican American Ethno-Catholicism in Houston, said that German Americans "historically played a central role in Houston, far outnumbering other whites such as the British, Irish, Canadians, French, Czechs, Poles, and Scandinavian groups who historically have comprised a smaller part of the city's ethnic mosaic."[11]

In 1910, prior to new waves of immigration from eastern and southern Europe, descendants of ethnic Whites who had founded Houston numerically outnumbered other ethnic groups who had later settled in Houston.[11] After European immigrants and their descendants assimilated into United States culture, they tended to develop with the city of Houston. Demographics at mid-century reflected a white majority, with Latino (mostly Mexican-American) and African-American minorities. The state legislature had disfranchised most blacks at the turn of the century and in practice, erected barriers to Latino voting as well.

After the Civil Rights Movement gained some successes, such as congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 to enforce minority constitutional rights, in the 1970s, white flight occurred in Houston as wealthier people moved to newer housing in suburbs, also choosing to avoid economic and racial integration of public schools in the city.[58] The city government used annexation as a strategy to mitigate White flight by annexing areas where White Americans moved.[59] Between the 1970-1971 and the 1971-1972 school years, enrollment at the Houston Independent School District decreased by 16,000. They were overwhelmingly ethnic Whites; 700 African-American students left the system.[58]

As the suburbs developed and Texas enjoyed the 1970s oil boom, many Anglo Whites settled directly in established suburbs, and they lacked any ties to inner city Houston. In 2004 about 33% of Anglo white people born in Harris County came from the Houston area, either by birth or from growing up there as children.[60]

Demographers Max Beauregard and Karl Eschbach, both of University of Houston Center for Public Policy, concluded from their analysis of the 2000 U.S. Census that white flight from the city continued to occur in the 1990s. In the decade prior to the 2000 U.S. Census, White residents left communities within Houston such as Alief, Aldine, Fondren Southwest, Gulfton, and Sharpstown. Other communities in Houston that lost large numbers of Whites by the 2000 census include Inwood Forest, Northline, Northside, and Spring Branch. Communities in other parts of Greater Houston that lost large numbers of Whites include Channelview, Cloverleaf, Galena Park, and Pasadena.[61]

Lori Rodriguez said, regarding the movement of white people in Greater Houston leading up to the year 2000, "Picture a stone dropped on the urban core and ripples of people spreading from within the Loop to the second-ring suburbs between the Loop and Beltway 8; and then beyond, to the outer-ring settlements and even unincorporated perimeter; Kingwood, The Woodlands, FM 1960."[61]

In the period between the 1990 and 2000 censuses, the largest growth of non-Hispanic White Americans within Greater Houston occurred in White-majority communities, such as Clear Lake City, Kingwood, northwest Harris County, the FM 1960 corridor, and The Woodlands.[61]

European residents and immigrants

19th and early 20th centuries

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Houston received numerous immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, many of whom entered through the Port of Galveston. As did other southern cities, Houston attracted "overflow" European immigrants first destined for industrial cities in the eastern seaboard and the Midwestern United States, which received larger numbers of Eastern and Southern Europeans in this period. In 1910, Houston had groups of Austro-Hungarians, Greeks, Italians, Russians, and Europeans from other populations. Those groups were smaller than the total of Mexican-Americans in Houston. By 1930, Houston had 8,339 first and-second generation Eastern and Southern European people. This was almost half of the size of Houston's Mexican-American population.[11]

Armenians

As of 2007 there were about 4,000-5,000 ethnic Armenians in the Houston area, according to St. Kevork parish council chairperson Vreij Kolandjian and pontifical visit host committee chairperson David Onanian.[62] Most are descendants of early 20th century immigrants who fled persecution the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. St. Kevork Armenian Church, which was established around 1982, serves as the Armenian Apostolic Church facility in Houston. As of 2007 about 10% of the ethnic Armenians in Houston are active in this church.[62]

Germans

German immigrants arrived in number following the revolutions of 1848 in the German states; they tended to oppose slavery and supported the Republican Party through the Reconstruction era.[63] The Second Ward, in the 1800s, had a heavily German American community. Thomas McWhorter, author of "From Das Zweiter to El Segundo, A Brief History of Houston’s Second Ward," wrote that "Second Ward became an unofficial hub of German-American culture and social life during the nineteenth century."[64] German settlers also predominated in Spring Branch, a community that later become a part of Houston, in the mid-1800s.[65]

Greeks

The first recorded ethnic Greeks in Houston, listed in the Houston City Directory of 1889-1890, were George and Peter Poleminacos. They worked as manual laborers, as they did not speak English. Kalliope Vlahos was the first Greek woman to arrive, in 1903; after her, more women and families with children began settling Houston.[66] Many of the earliest settlers planned to make money in the U.S. and then return to their homelands. Several Greeks became businessowners;[67] historically many Greeks operated cafes and sweets shops in Downtown Houston.[68] The capital start-up costs of such shops were relatively low.

Italians

Brina D'Amico, a member of the D'Amico restaurateur family, said in 2014 that most Italian-American families in Houston were of Sicilian origins, and their immigrant ancestors had entered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries at the Port of Galveston.[69]

Norwegians

In the late 1800s, more Norwegians arrived at the port of Galveston than any other United States port other than Ellis Island in New York City. Many of the Norwegians who were processed through Galveston migrated to join compatriots in farming areas of Minnesota and other areas in the Midwestern United States.[70]

Late 20th century to present

Since the late 20th century, new immigrants have arrived from Norway, Russia, and the Mideast. In addition, there are nationals from the UK and other countries who work here for a period of time. Lasse Sigurd Seim, the consul general of the Norwegian Consulate General, Houston, described the estimated 5,000–6,000 Norwegians in the Houston area around 2008 as the largest concentration of ethnic Norwegians outside of Scandinavia. Jenalia Moreno of the Houston Chronicle said during that year that the influx of Norwegians into Greater Houston was "relatively new" and related to Norway's also having a major oil industry.[70]

In a 2004 Houston Chronicle article, Nikolai V. Sofinskiy, the first consul general of the Consulate-General of Russia in Houston, said that there were around 40,000 Russian speakers in the Houston area. [71]

As of 1983 there were about 10,000 British nationals in Houston.[72] Annette Baird of the Houston Chronicle said that, as of December 2000, the number of British citizens in Greater Houston was estimated to be over 40,000. Grainne O'Reilly-Askew, the first headmistress of the British School of Houston, said that before the school was established, British companies encountered difficulty in convincing their executives to relocate to Greater Houston, since the area previously did not have a school using the British educational system.[73] John Major, the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, attended the school's official opening.[74]

Iranians/Persians

As of 1994, over 50,000 ethnic Iranians live in Houston. As of that year, 12 city blocks along Hillcroft Avenue, from Westheimer Road to a point just south of Westpark, contain a Persian business district including shops and restaurants. Allison Cook of the Houston Press referred to the area as "Little Persia".[75]

As of 1990 most Iranians/Persians in Houston are not religious.[76]

As of 2000, Iranians were one of the two main Zoroastrian groups in Houston. As of that year the total number of Iranians in Houston of all religions is larger than the total Parsi (generally immigrants from India) population by a 10 to 1 ratio.[24]

Rustomji wrote that as of 2000, because of the historic tensions between the Parsi and Iranian groups, the Iranians in Houston did not become full members of the Zoroastrian Association of Houston (ZAH), which was majority Parsi. Rustomji stated that Iranian Zoroastrians "attend religious functions sporadically and remain tentative about their ability to fully integrate, culturally and religiously, with Parsis."[24] In 1996 the Iranian population had its largest attendance at a ZAH event when it attended Jashne-e-Sade, an event the community created for ZAH. By 2000 some Muslim Iranians who were opposed to fundamentalism in the mosques, began attending Zoroastrian events. Rustomji wrote in 2000 that from 2000 to 2005, Iranians were expected to make up a greater proportion of ZAH.[24]

As of 2006 most Bahá'í Center members are Persians.[77] As of 2010 many Houston Bahá'í are refugees from Iran. In Iran many of their relatives and parents suffered religious and political persecution, being arrested and/or executed.[78]

After Iranian student and activist Gelareh Bagherzadeh was murdered in Houston in 2012, Lomi Kriel of the Houston Chronicle stated that "The case has been complicated by the possible Iranian link and the close-knit nature of Houston's Iranian community. Many have been either afraid to talk or reluctant to disclose details they consider private or disrespectful."[79] The perpetrator, Ali Irsan, was later convicted and sentenced to death for the crime,[80] an honor killing in retaliation against Bagherzadeh's encouragement of Irsan's daughter to leave Islam and marry a Christian man.[81][82]

Arabs

Badr stated that as of 2000, about 10% of the Islamic Society of Greater Houston (ISGH) consists of ethnic Arabs, from a variety of Middle East nations. She added that the percentage of Arabs among Houston's Muslim population is estimated by some to be "as high as 30%."[83] According to Badr, from 1990 to 2000 many Arabs began to found their own mosques and Islamic schools separate from the ISGH. They disagreed about various issues with other members of the Society, including the language of the Friday sermons in the mosques, the operations of Sunday schools and full-time schools, and monetary collection and distribution within the community.[83]

As of 2014 U.S. Census estimates, 23,300 people in the Houston area speak the Arabic language; this is a one-third increase in the number of Arabic speakers compared to 2009.[84]

The Arab Times is published in the Houston area.

Ethnoreligious groups

Jews

Jews were part of the great waves of immigration from eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, coming especially from the Russian Empire, that than included Poland and Ukraine. Most entered through the Port of Galveston. Jewish aid societies encouraged immigrants to settle in the South, as the northeastern cities were absorbing so many from Europe.

By around 1987 about 42,000 Jews lived in Greater Houston.[85] In 2008 Irving N. Rothman, author of The Barber in Modern Jewish Culture: A Genre of People, Places, and Things, with Illustrations, wrote that Houston "has a scattered Jewish populace and not a large enough population of Jews to dominate any single neighborhood." He wrote that the city's "hub of Jewish life" is the Meyerland community.[86]

Copts

Christian Egyptians and some North Africans have historically belonged to the Coptic Orthodox Church. A sufficient number of immigrants from these areas have settled in Houston since the late 20th century to establish churches and the Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States. As of 2004, there were three Coptic Orthodox churches in Houston: St. Mark Coptic Orthodox Church in Bellaire, the St. Mary and Archangel Michael Church in northwest Harris County, and the Archangel Raphael Coptic Orthodox Church in Clear Lake City. The St. Mary and Archangel Michael church began church services on July 25, 2004, had 200 families in August of that year, and was built at a cost of $2.5 million.[87] The St. Mary and Archangel Michael church is the largest Copt church in the Houston area.[88]

In the late 1960s there were far fewer Coptic families. They were served by a priest from Los Angeles, who would fly monthly to Houston and hold mass in a borrowed Orthodox church or in a private house.[87] From 1968 to 2006, more than 600 Coptic families moved to Houston. Due to sectarian strife against Copts in Egypt, by 2006 the number of immigrants had increased and membership of Copt churches in Houston was growing.[88]

In 2006 Gregory Katz of the Houston Chronicle said that, partly because many Copt church leaders are accustomed to anti-Copt attitudes in Egypt, those who come to Houston are not accustomed to speaking freely about their religious beliefs. They "do not mingle easily with the rest of the large Christian community in the Houston area".[88]

After the 2011 Alexandria bombing in Egypt, Houston Coptic churches cancelled their Coptic Christmas services.[89]

Parsis

The Parsi in 2000 made up one of the two chief ethnic groups practicing the Zoroastrian religion. As of that year the total number of Iranians of all religions in Houston was larger than the total Parsi population by a ratio of 10 to 1.[24] As of 2000 the members of the Zoroastrian Association of Houston (ZAH) are majority Parsi. Rustomji wrote that because of that and the historic tensions between the Parsi and Iranian groups, many Iranians in Houston did not become full members of the ZAH. Rustomji said that Iranian Zoroastrians "attend religious functions sporadically and remain tentative about their ability to fully integrate, culturally and religiously, with Parsis."[24]

Sikhs

In 2012 the Sikh National Center stated that the city of Houston has 7,000 to 10,000 Sikhs. The Gurdwara Guru Teg Bahadur Sahib Ji is a Sikh temple in Houston,[90] located off of Fairbanks North Houston. As of 2012 the majority of the city's Sikhs originate from the portion of Punjab in India.[28]

Maronites

As of 2008 Our Lady of the Cedars Maronite Catholic Church is Houston's only Maronite Church. That year, Christine Dow, a spokesperson for the church, stated that there were about 500 families who were members, and that the community, since the 1990s, had increased.[91] Richard Vara of the Houston Chronicle wrote that in 1991 there had "only a handful of registered families" in the Houston Maronite church.[92]

References

- Badr, Hoda. "Al Noor Mosque: Strength Through Unity" (Chapter 11). In: Chafetz, Janet Salzman and Helen Rose Ebaugh (editors). Religion and the New Immigrants: Continuities and Adaptations in Immigrant Congregations. AltaMira Press, October 18, 2000. ISBN 0759117128, 9780759117129.

- Bell, Roselyn. "Houston." In: Tigay, Alan M. (editor) The Jewish Traveler: Hadassah Magazine's Guide to the World's Jewish Communities and Sights. Rowman & Littlefield, January 1, 1994. p. 215-220.

ISBN 1568210787, 9781568210780.

- Content also in: Tigay, Alan M. Jewish Travel-Prem. Broadway Books, January 18, 1987. ISBN 0385241984, 9780385241984.

- Brady, Marilyn Dell. The Asian Texans. Texas A&M University Press, 2004. ISBN 1585443123, 9781585443123.

- Fischer, Michael M. J. and Mehdi Abedi. Debating Muslims: Cultural Dialogues in Postmodernity and Tradition. University of Wisconsin Press, 1990. ISBN 0299124347, 9780299124342.

- Klineberg, Stephen L. and Jie Wu. "DIVERSITY AND TRANSFORMATION AMONG ASIANS IN HOUSTON: Findings from the Kinder Institute’s Houston Area Asian Survey (1995, 2002, 2011)" (" (Archive). Kinder Institute for Urban Research, Rice University. February 2013.

- Rodriguez, Nestor. "Hispanic and Asian Immigration Waves in Houston." in: Chafetz, Janet Salzman and Helen Rose Ebaugh (editors). Religion and the New Immigrants: Continuities and Adaptations in Immigrant Congregations. AltaMira Press, October 18, 2000.

ISBN 0759117128, 9780759117129.

- Also available in: Ebaugh, Helen Rose Fuchs and Janet Saltzman Chafetz (editors). Religion and the New Immigrants: Continuities and Adaptations in Immigrant Congregations. Rowman & Littlefield, January 1, 2000. 0742503909, 9780742503908.

- Rodriguez, Nestor P. (University of Houston) "Undocumented Central Americans in Houston: Diverse Populations." International Migration Review Vol. 21, No. 1 (Spring, 1987), pp. 4–26. Available at JStor.

- Rothman, Irving N. The Barber in Modern Jewish Culture: A Genre of People, Places, and Things, with Illustrations. Edwin Mellen Press, August 14, 2008.

- Rustomji, Yezdi. "The Zoroastrian Center: An Ancient Faith in Diaspora." in: Chafetz, Janet Salzman and Helen Rose Ebaugh (editors). Religion and the New Immigrants: Continuities and Adaptations in Immigrant Congregations. AltaMira Press, October 18, 2000. ISBN 0759117128, 9780759117129.

Notes

- ↑ Strait, John B ; Gong, Gang. "Ethnic Diversity in Houston, Texas: The Evolution of Residential Segregation in the Bayou City, 1990–2000," Population Review, 2010, Vol.49(1). cited: p. 56. "During the 1990s Houston emerged as a member[...]"

- ↑ Strait, John B ; Gong, Gang. "Ethnic Diversity in Houston, Texas: The Evolution of Residential Segregation in the Bayou City, 1990–2000." Population Review, 2010, Vol.49(1). cited: p. 64. "First, during the 1990s all non-white populations in Houston became increasingly segregated from and less residentially exposed to whites, while becoming more integrated with one another.[...]"

- ↑ Gardner, David. "Revealed: The maps that show the racial breakdown of America’s biggest cities," Daily Mail. September 26, 2010. Retrieved on November 12, 2011.

- ↑ Hegstrom, Edward. "Shadows cloaking immigrants prevent accurate count.", Houston Chronicle (February 21, 2006).

- ↑ Casey, Rick. "City Hall Latino win may end up as a loss instead," Houston Chronicle. April 28, 2011. Retrieved on June 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Strait, John B ; Gong, Gang. "Ethnic Diversity in Houston, Texas: The Evolution of Residential Segregation in the Bayou City, 1990–2000." Population Review, 2010, Vol.49(1). cited: p. 58.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Nestor, "Undocumented Central Americans in Houston: Diverse Populations," p. 4.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Lori. "Targeting Spanish-speaking riders, Taxis Fiesta's business blossoms as Hispanic communities spread across the city / Latino growth drives cab boom," Houston Chronicle, November 28, 2005. B1 MetFront. Retrieved on December 31, 2011. Quote: "Since 1985, said Eschbach, the Hispanic population has tripled, and now two of every five Harris County residents are Hispanic. Hispanics are becoming the dominant population group in most areas out to and past Beltway 8. The exceptions are the historically black neighborhoods northeast and south of downtown and high-dollar white communities from West University Place through Uptown and Memorial."

- ↑ Money Smart Press Release. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

- ↑ Power Speaks Spanish in Texas. Puerto Rico Herald

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Treviño, Robert R. The Church in the Barrio: Mexican American Ethno-Catholicism in Houston. UNC Press Books, February 27, 2006. 29. Retrieved from Google Books on November 22, 2011. ISBN 0-8078-5667-3, ISBN 978-0-8078-5667-3.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Nestor, "Hispanic and Asian Immigration Waves in Houston," p. 38.

- 1 2 3 Rodriguez, Nestor, "Hispanic and Asian Immigration Waves in Houston," p. 37.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Nestor, "Hispanic and Asian Immigration Waves in Houston," p. 37-38.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Nestor, "Hispanic and Asian Immigration Waves in Houston," p. 41.

- ↑ "Number Crunching." PBS Newshour. August 25, 1998. Retrieved on March 17, 2012.

- ↑ Snyder, Mike. "Survey provides insight into Chinese community." Houston Chronicle. October 2, 2002. Retrieved on April 22, 2013.

- ↑ Moreno, Jenalia. "Houston's 'Chinatown' near Beltway 8 sparks banking boom." Houston Chronicle. Sunday February 18, 2007. Retrieved on October 16, 2011.

- ↑ Harkinson, Josh. "Tale of Two Cities." Houston Press. Thursday December 15, 2005. 2. Retrieved on March 17, 2012.

- ↑ Collier, Kiah. "It's official: Air China to begin flights to Beijing." Houston Chronicle. January 15, 2013. Retrieved on April 21, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Klineberg and Wu, p. 12.

- ↑ Cook, Allison. "The Grand Tour." Texas Monthly. Emmis Communications, January 1983. Vol. 11, No. 1. Start page p. 98. ISSN 0148-7736. Cited p. 109.

- ↑ Shilcut, Katharine. "Little India." Houston Press. Wednesday May 25, 2011. 4. Retrieved on May 26, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rustomji, p. 249.

- ↑ Shilcut, Katharine. "Little India." Houston Press. Wednesday May 25, 2011. 1. Retrieved on May 26, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Vara, Richard. "Area Asian Catholics to come together in celebration." Houston Chronicle. August 21, 1999. Religion p. 1. NewsBank Record: 3159522. Available from the Houston Chronicle website's newspaper databases, accessible with a library card and PIN.

- 1 2 3 Patel, Purva. "Asian-American newspapers reach a flourishing market." Houston Chronicle. September 30, 2007. Retrieved on May 25, 2014.

- 1 2 "Houston Sikh community reacts to shooting." Houston Chronicle. August 6, 2012. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Kumar, Seshadri. "Sugar Land engineer pens novel" (Archived October 30, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.). Houston Chronicle. December 20, 2006. Retrieved on October 7, 2014.

- ↑ Patel, Purva. "Pakistani center touts retail concept as a novel idea." ("Pakistani center pays its way Retail space included as old H-E-B remodeled") Houston Chronicle. January 16, 2007. Retrieved on May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Badr, p. 193.

- ↑ "header.jpg" (Archive). Bangladesh Association, Houston. Retrieved on September 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Home." Bangladesh Association, Houston. Retrieved on September 26, 2014.

- ↑ Christian, Carol. "Bangladeshis plan SW Harris center More than 10,000 from ex-East Pakistan live in Houston" (Archive). Houston Chronicle. June 2, 2011. Retrieved on June 3, 2011. "As envisioned, the $2.5 million facility at 13145 Renn Road in southwest Harris County will have an auditorium and classrooms as well as an outdoor sports complex and playground."

- ↑ "Bangladesh-American Center of Houston" (Archived May 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.). India Herald. Retrieved on May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Cook, Allison. "The Grand Tour." Texas Monthly. Emmis Communications, January 1983. Vol. 11, No. 1. ISSN 0148-7736. START: p. 98. CITED: p. 144.

- ↑ Lomax, John Nova. "The Seoul of Houston: The Weather Was Not the Strong Point on Long Point Archived August 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.." Houston Press. January 30, 2008.

- ↑ Hung, Melissa (2000-04-13). "Cambodian Queen". Houston Press. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ↑ Walsh, Robb (2017-09-07). "One Houston community's response to Harvey: Keep making the doughnuts". Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- 1 2 Hardy, Michael (2018-01-22). "Big Trouble in Little Cambodia". Texas Observer. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- 1 2 McCoy, Terrence (2012-09-06). "Cambodian Weed". Dallas Observer. Retrieved 2018-01-24. - Published in the Dallas Observer as: "a Hidden Texas Farming Village, the Making (and Selling) of a Cambodian Bumper Crop" and in Westword as "For some Cambodians in Houston, water spinach provides a figurative and literal lifeline"

- ↑ Wolf, Lauren (November 2009). "It Takes a Texas Village to Raise Spinach". Texas Monthly. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ↑ Cook, Allison. "The Grand Tour." Texas Monthly. Emmis Communications, January 1983. Vol. 11, No. 1. ISSN 0148-7736. Start: p. 98. Cited: p. 105.

- ↑ Aqui, Reggie (December 27, 2004). "Houston's connection to Indonesian earthquake victims". KHOU-TV.

- ↑ Giglio, Mike. "The Burmese Come to Houston." Houston Press. September 1, 2009. 1. Retrieved on December 19, 2009.

- ↑ Finkel, Adam N. Worst Things First?: The Debate Over Risk-Based National Environmental Priorities. Resources for the Future, 1995. 249. Retrieved from Google Books on October 6, 2011. ISBN 0-915707-76-4, ISBN 978-0-915707-76-8

- ↑ "Why African Americans Are Moving Back to the South", Christian Science Monitor, 16 March 2014

- 1 2 Corey, Charles W. "Houston Looking to Expand a "Natural" Relationship with Africa." U.S. State Department. November 21, 2003. Retrieved on December 11, 2009.

- 1 2 Romero, Simon. "Energy of Africa Draws the Eyes of Houston," The New York Times, September 23, 2003. 1. Retrieved on October 24, 2011.

- ↑ http://hmaacvoices.org/2014/05/15/the-african-republic-of-houston/

- ↑ "The African Republic of Houston." Houston Museum of African American Culture. May 15, 2014. Retrieved on July 19, 2015.

- ↑ Casimir, Leslie. "Data show Nigerians the most educated in the U.S." Houston Chronicle. Tuesday May 20, 2008. Retrieved on July 19, 2015.

- ↑ Plushnick-Masti, Ramit. "Nigerians in Dallas, Houston call for schoolgirls' release" (Archived February 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.). Associated Press at The Dallas Morning News. May 9, 2014. Retrieved on July 19, 2015.

- ↑ Lawal, Lateef. "United Continental Launches Inaugural Flight Between Houston-Lagos." Eagle News Nigeriana at OfficialWire. November 17, 2011. Retrieved on November 17, 2011. Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Moreno, Jenalia. "Houston gets first scheduled nonstop flight to Africa" (Archived November 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.). Houston Chronicle, November 15, 2011. Retrieved on November 17, 2011.

- ↑ Mutzabaugh, Ben. "United Airlines ending its last flight to Africa" (Archived June 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.). USA Today. May 27, 2016. Retrieved on May 29, 2016.

- 1 2 Vara, Richard. "Ethiopian believers find strength in Orthodox church." Houston Chronicle. February 15, 2003. Retrieved on May 5, 2014.

- 1 2 "White flight accompanies integration," Associated Press at The Telegraph-Herald. January 17, 1972. 6 Retrieved from Google Books (6 of 38) on October 3, 2011.

- ↑ "City bucks the trend Others dying, Houston thrives," Associated Press, Southeast Missourian, 18 January 1975. Page 4. Retrieved from Google Books (8 of 17) on November 3, 2011.

- ↑ Bryant, Salatheia (2004-02-08). "Black suburbanites trying city living". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2017-01-01.

- 1 2 3 Rodriguez, Lori. "THE CENSUS / Census study: White flight soars / UH analysis spots segregation trend," Houston Chronicle,. 15 April 2001 (Sunday). A1. Retrieved on December 30, 2011.

- 1 2 Vara, Richard. "Head of Armenian Apostolic Church visiting Houston." Houston Chronicle. Saturday October 20, 2007. Retrieved on April 27, 2016.

- ↑ Forty-Eighters from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ↑ McWhorter, Thomas. "From Das Zweiter to El Segundo, A Brief History of Houston’s Second Ward." Houston History Magazine. Volume 8, No. 1, pp. 39-42. CITED: p. 40.

- ↑ Spring Branch, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ↑ Cassis, Irene and Dr. Constantina Michalos. Greeks in Houston (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing, August 5, 2013. ISBN 1439643784, 9781439643785. p. 17.

- ↑ Cassis, and Michalos. Greeks in Houston (2013), p. 19.

- ↑ Cassis and Michalos. Greeks in Houston (2013) p. 18.

- ↑ Steinberg, Kaitlin. "Meet the First Families of Houston Food." Houston Press. Wednesday February 26, 2014. Retrieved on February 29, 2016.

- 1 2 Moreno, Jenalia. ""For Norway, Houston is Oslo on the bayou" / Many from Scandinavian nation, which has a major oil industry, are finding opportunities in Texas," Houston Chronicle, August 17, 2008. Business 1. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Lezon, Dale. "Energy, space draw Russian consulate here." Houston Chronicle. May 26, 2004. A21 MetFront. Retrieved on February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Cook, Allison. "The Grand Tour." Texas Monthly. Emmis Communications, January 1983. Vol. 11, No. 1. ISSN 0148-7736. START: p. 98. CITED: p. 101.

- ↑ Baird, Annette. "British school to expand to accommodate demand" (Archive). Houston Chronicle. Wednesday December 20, 2000. ThisWeek 2. Retrieved on December 9, 2010.

- ↑ Staff. "A major opening." Houston Chronicle. Thursday September 21, 2000. A36. Retrieved on December 9, 2010. Available from the Houston Public Library website, accessible with a library card.

- ↑ Cook, Allison. "Touring Little Persia," Houston Press. September 15, 1994. p. 1. Retrieved on May 12, 2014.

- ↑ Fischer and Abedi, p. 269.

- ↑ Karkabi, Barbara. "Bahai Faith adherents value unity, education." Houston Chronicle. November 11, 2006. Houston Belief. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Shellnutt, Kate. "Local Baha’is pray for jailed leaders in Iran," Houston Chronicle, February 8, 2010. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Kriel, Lomi (2012-08-06). "Still no answers 6 months after Iranian student's killing". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ↑ Rogers, Brian (2018-08-14). "Jury delivers death sentence for Jordanian immigrant convicted of two Houston-area 'honor killings'". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ↑ "TANGLED WEB: Sorting out the timeline of the so-called Houston 'honor killings'". KTRK-TV. 2018-06-25. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ↑ Rogers, Brian (2018-06-18). "Wife testifies her husband confessed to pulling the trigger in one of two Houston-area 'honor killings'". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- 1 2 Badr, p. 207

- ↑ Hernandez, Haley. "Protest held against new Arabic school in HISD" (Archived 2015-08-31 at WebCite). KHOU-TV. August 24, 2015. Retrieved on August 31, 2015.

- ↑ Bell, p. 217.

- ↑ Rothman, p. 358.

- 1 2 Vara, Richard. "New home is 'miracle' for Coptic Christians." Houston Chronicle. August 21, 2004. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Katz, Gregory. "Egyptian Coptic Christians find bright future in Houston." Houston Chronicle. December 6, 2006. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Shellnutt, Kate. "Coptic Christians in Houston cancel Christmas services." Houston Chronicle. January 6, 2011. Retrieved on May 25, 2014.

- ↑ Chitwood, Ken. "Houston Sikhs hope to avert tragedy by educating on religion." Houston Chronicle. August 9, 2012. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Murphy, Bill. "Maronite cardinal tells of threat to Lebanon." Houston Chronicle. May 20, 2008. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- ↑ Vara, Richard. "Maronite cardinal visits Houston." Houston Chronicle. May 23, 2008. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ethnic groups in Houston. |

- Emerson, Michael O., Jenifer Bratter, Junia Howell, P. Wilner Jeanty, and Mike Cline. "Houston Region Grows More Racially/Ethnically Diverse, With Small Declines in Segregation A Joint Report Analyzing Census Data from 1990, 2000, and 2010" (Archive" (Archive). Kinder Institute for Urban Research and the Hobby Center for the Study of Texas, Rice University.

- Kriel, Lomi. "Newcomers help put 'white flight' to rest in area." Houston Chronicle. June 25, 2014.

- Fountain, Ken. "Ethnicity, economy highlight Houston area survey results." The Examiner. ASP Westward (Houston Community Newspapers). Saturday April 23, 2011.