Eora

| Eora people | |

|---|---|

|

aka: Ea-ora, Iora, and Yo-ra Eora (AIATSIS), nd (SIL) | |

Sydney Basin bioregion | |

| Hierarchy | |

| Language family: | Pama–Nyungan |

| Language branch: | Yuin–Kuric |

| Language group: | Yora |

| Group dialects: | Dharug |

| Area | |

| Bioregion: | Sydney Basin |

| Location: | Sydney, New South Wales |

| Coordinates: | 34°S 151°E / 34°S 151°ECoordinates: 34°S 151°E / 34°S 151°E |

| Notable individuals | |

The Eora /jʊərɑː/ (Yura)[1] are an indigenous Australian people of New South Wales. Eora is the name given by the earliest settlers[2][lower-alpha 1] to a group of indigenous people belonging to the clans along the coastal area of what is now known as the Sydney basin, in New South Wales, Australia. Contact with the first white settlement's bridgehead into Australia quickly devastated much of the population through epidemics of smallpox and other diseases. Their descendants live on, though their language, social system, way of life and traditions are mostly lost.

Radiocarbon dating suggests human activity occurred in and around Sydney for at least 30,000 years, in the Upper Paleolithic period.[3][4] However, numerous Aboriginal stone tools found in Sydney's far western suburbs gravel sediments were dated to be from 45,000 to 50,000 years BP, which would mean that humans could have been in the region earlier than thought.[5][6]

Ethnonym

The meaning of the Eora ethnonym is not known. Contemporary accounts state that it simply meant "people",[1] though one theory proposes that the word was constructed from e (yes) and ora (country).[7] Descendants of the Eora and use the word as a regional name.[7]

Language

The language spoken by the Eora has, since the time of R. H. Mathews, been called Dharuk, which generally refers to what is known as the inland variety, as opposed to the coastal form Iyora (or Eora).[8] It was described as "extremely grateful to the ear, being in many instances expressive and sonorous," by David Collins.[9] It became extinct after the first two generations, and has been partially reconstructed in some general outlines from the many notes made of it by the original colonists, in particular from the notebooks of William Dawes,[10] who picked up the languages spoken by the Eora from his companion Patyegarang.[11]

Some of the words of Aboriginal language still in use today are from the Eora (possibly Tharawal) language and include: dingo=dingu; woomera=wamara; boomerang=combining wamarang and bumarit, two sword-like fighting sticks; corroboree=garabara;[12] wallaby, wombat, waratah, and boobook (owl).[13] The Australian bush term bogey (to bathe) comes from a Port Jackson Dharuk root buugi-.[14][15]

Country

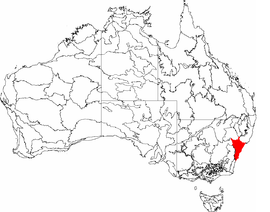

Eora territory, composed of sandstone coastal outcrops and ridges, coves, mangrove swamps, creeks and tidal lagoons, was estimated by Norman Tindale to extend over some 700 square miles (1,800 km2), from Port Jackson's northern shores up to the Hawkesbury River plateau's margins, around Pittwater. Its southern borders were as far as Botany Bay and the Georges River.[16] Westwards it extended to Parramatta.[17] In terms of tribal boundaries, the Kuringgai lay to the north: on the Western edges were the Darug; and to the south, around Kundul were the Gwiyagal, a northern clan of the Tharawal.[18] Their clan identification, belonging to numerous groups of about 50 members, overrode more general Eora loyalties, according to Governor Phillip, a point first made by David Collins[2][lower-alpha 2] and underlined decades later by a visiting Russian naval officer, Aleksey Rossiysky in 1814, who wrote:

each man considers his own community to be the best. When he chances to meet a fellow-countryman from another community, and if someone speaks well of the other man, he will invariably start to abuse him, saying that he is reputed to be a cannibal, robber, great coward and so forth.[19]

Bands and clans

Eora is used specifically of the people around the first area of white settlement in Sydney.[20] The generic term Eora generally is used with a wider denotation to embrace some 29 bands. The sizes of bands, as opposed to clans, could range from 20 to 60 but averaged around 50 members. -gal denominates the clan or extendeds family group[1] affixed to the place name.[21]

- Cammeraygal. (Port Jackson, North Shore, Manly Cove

- Wanegal. (South of the Parramatta River.[1] Long Cove in Rose Hill)

- Cadigal. (South side of Port Jackson)[lower-alpha 3]

- Walumedigal. ("Snapper fish clan". North of the Parramatta River.[23] Milson Point, North Shore opposite Sydney Cove).[22]

- Burramattagal. ("Eel place clan"= at the source of the Parramatta River)[24]

- Bidjigal. (Castle Hill)

- Norongeragal. (locality unknown)

- Borogegal. (Bradley Head)

- Karegal. (Broken Bay, or southern vicinity)

- Gweagal. (Southern shore of Botany Bay)[25][11]

The Wangal, Wallumettagal and Burramattagal constituted the three Parramatta saltwater peoples.[1] It has been suggested that these had a matrilineal pattern of descent.[26]

Lifestyle

The traditional Eora people were largely coastal dwellers and lived mainly from the produce of the sea. They were expert in close-to-shore navigation, fishing, cooking, and eating in the bays and harbours in their bark canoes. The Eora people did not grow or plant crops; although the women picked herbs which were used in herbal remedies. They made extensive use of rock shelters, many of which were later destroyed by settlers who mined them for their rich concentrations of phosphates, which were then used for manure.[27] Wetland management was important: Queenscliff, Curl Curl and the Dee Why lagoons furnished abundant food, culled seasonally. Summer foods consisted of oyster, netted mullet caught in nets, with fat fish caught on a line and larger fish taken on burley and speared from rock ledges. As summer drew to an end, feasting on turtle was a prized occasion. In winter, one foraged for and hunted possum, echidna, fruit bats, wallaby and kangaroo.[28]

The Eora placed a time limit on formal battles engaged in order to settle inter-tribal grievances. Such fights were regulated to begin late in the afternoon, and to cease shortly after twilight.[29]

History

The first Sydney-area contact occurred when James Cook's Endeavour anchored in Botany Bay. A drawing, thought recently to be the handiwork of the Polynesian navigator Turpaia who was on board Cook's ship, survives depicting Aboriginals in Botany Bay, around Kurnell.[30] The Eora were at first bewildered by settlers wreaking havoc on their trees and landscape. After an early contact with the Tharawal, meetings with Eora soon followed: they were disconcerted by the suspicion these visitors were ghosts, whose sex was unknown, until the delight of recognition ensued when one sailor dropped his pants to clarify their perplexity.[31] There were 17 encounters in the first month, as the Eora sought to defend their territorial and fishing rights. Misunderstandings were frequent: Governor Phillip mistook scarring on women's temples as proof of men's mistreatment, when it was a trace of mourning practices.[32] From the outset, the colonizers kidnapped Eora in order to train them to be intermediaries between the settlers and the indigenous people. The first man to suffer this fate was the Guringai Arabanoo, who died soon after in the smallpox epidemic of 1789.[33][lower-alpha 4] Several months later, Bennelong and Colebee were captured for a similar purpose. The latter escaped while Bennelong stayed for some months, learning more about the British food needs, etiquette, weaponry and hierarchy than anything they garnered from conversing with him.[35] Eventually Phillip built a brick house for the former at the site of the present Sydney Opera House at Tubowgulle, (Bennelong Point). The hut was demolished five years later.[33][36]

When the First Fleet of 1300 convicts, guards, and administrators arrived in January 1788, the Eora numbered about 1,500.[18] By early 1789 frequent remarks were made of great numbers of decomposed bodies of Eora natives which settlers and sailors came across on beaches, in coves and in the bays. Canoes, commonly seen being paddled around the harbor of Port Jackson, had disappeared.[37][38] The Sydney natives called the disease that was wiping them out (gai-galla) and what was diagnosed as a smallpox epidemic in April 1789 effectively decimated the Port Jackson tribes.[38] Robert King states that of an estimated 2,000 Eora, half (Bennelong's contemporary estimate[1]) were decimated by the contagion. Smallpox and other introduced disease, together with starvation from the plundering of their fish resources, is said to have accounted for the virtual extinction of the 30-50 strong Cadigal clan on the peninsula (kattai) between Sydney Cove and South Head.[39] J. L. Kohen estimates that between 50 and 90 percent of members of local tribes died during the first three years of settlement. No settler child showed any symptoms of the disease. The English rebuffed any responsibility for the epidemic.[lower-alpha 5] It has been suggested that either rogue convicts/settlers or the governing authority itself spread the smallpox when ammunition stocks ran low and muskets, when not faulty, proved inadequate to defend the outpost.[41] It is known that several officers of the Fleet had experience of war in North America where using smallpox to diminish tribes had been used as early as 1763.[42]

Several foreign reports, independent of English sources, such as those of Alexandro Malaspina in 1793 and Louis de Freycinet in 1802 give the impression that the settlers' relations with the Eora who survived the epidemic were generally amenable. Governor Phillip chose not to retaliate after he was speared by Willemering at Kayemai(Manly Cove) on 7 September 1790, in the presence of Bennelong who had, in the meantime, "gone bush".[43][44] Governor William Bligh wrote in 1806:Much has been said about the propriety of their being compelled to work as Slaves, but as I have ever considered them the real Proprietors of the Soil, I have never suffered any restraint whatever on these lines, or suffered any injury to be done to their persons or property'.[45]

Governor Macquarie established a Native Institution to house aboriginal and also Maori children in order to civilize them, on the condition they could only be visited by their parents on one day, 28 December, a year. It proved a disaster, and many children died there.[46] Aboriginal people continued to camp in central Sydney until they were evicted from their camps, such as the one at Circular Quay in the 1880s.[33]

Song

An Eora song has survived. It was sung by Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne at a concert in London in 1793. Their words and the music were transcribed by Edward Jones and published in 1811.[47] A modern version of the song was rendered by Clarence Slockee and Matthew Doyle at the State Library of NSW, August 2010, and may be heard online.[48]

Notable people

- Arabanoo, kidnapped by militia of thwe First Fleet in order to be trained as interpreter.

- Bennelong, a Wangal of the Eora peoples,[22] served as a link between the British colony at Sydney and the Eora people in the early days of the colony. He was given a brick hut on what became known as Bennelong Point where the Sydney Opera House now stands. He traveled to England in 1792 along with Yemmerrawanne and returned to Sydney in 1795. His wife, Barangaroo, was an important Cammeraygal woman from Sydney's early history who was a powerful and colourful figure in the colonisation of Australia. She is commemorated in the naming of the suburb of Barangaroo, in east Darling Harbour.[49]

- Barangaroo

- Yemmerrawanne

- Patyegarang, an Eora who taught her paramour William Dawes Eora languages.

- Pemulwuy, a Bidjigal clan warrior who lead the Eora resistance for over a decade.

Alternative names

- Ea-ora, Iora, Yo-ra

- Kameraigal. (name of an Eora horde)

- Kem:arai (toponym of northern area of Port Jackson).

- Kemmaraigal, Camera-gal, Camerray-gal, Kemmirai-gal

- Cammeray, Cammera

- Gweagal. (Eora horde on the south side of Botany Bay)

- Bedia-mangora

- Gouia-gul

- Gouia

- Wanuwangul. (Eora horde near Long Nose Point, Balmain, and Parramatta)

- Kadigal/ Caddiegal. (horde on south side of Port Jackson).[16]

Some words

Notes

- ↑ "Neither the word lists nor the contexts in which eora is used in these early accounts suggest the word eora was associated with a specific group of people or a language."

- ↑ The natives of the coast, whenever speaking of those of the interior, constantly expressed themselves with contempt and marks of disapprobation. Their language was unknown to each other, and there was not any doubt of their living in a state of mutual distrust and enmity

- ↑ Their traditional land and waters are south of Port Jackson, stretching from South Head to Petersham. The people described by British settlers as the Eora people were probably Cadigal people, the Aboriginal tribe of the inner Sydney region in 1788 at the time of first European settlement. The Cadigal clan western boundary is approximately the Balmain peninsula.[22]

- ↑ Warren places this in the context of the struggle for scarce food resources:"Phillip sought to resolve these issues, but he probably made matters worse. In December, he sent marines out to capture some Aborigines, and several musquets were fired and rocks and spears were thrown. One native, Arabanoo, was captured. Shortly after, he was displayed in front of his home clan in a rather naïve effort to show them he was still alive."[34]

- ↑ King cites from a contemporary Spanish report, "Examen politico de las colonias inglesas en el Mar Pacifico,":'Wary to avoid the accusation of this being the first fruit of their coming to these distant regions, the English allege in their favour that the epidemic manifested itself at almost the same time as their arrival, stating on the other hand legally that in all of the First Fleet there had not been anyone who had carried it; that they found it distinguished among the Natives with its own name; and that finally either this sickness was known before the coming of the Europeans, or that its introduction must have been brought by the French Ships of the Comte de la Perouse. It would be an idle rashness to wish now to entertain ourselves by examining this question: for our purpose it suffices to demonstrate that what will be easier and sooner will be the destruction rather than the civilisation of these unhappy people.'[40]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Smith 2009, p. 10.

- 1 2 Attenbrow 2010b, p. 35.

- ↑ Macey 2007.

- ↑ Heiss & Gibson 2013.

- ↑ Attenbrow 2010a, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Stockton & Nanson 2004, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 Broome 2010, p. 15.

- ↑ Troy 1992, p. 1, n.2.

- ↑ Collins 1798, p. 609.

- ↑ Troy 1992, pp. 145–170.

- 1 2 Foley 2007, p. 178.

- ↑ Troy 1992.

- ↑ Dawes.

- ↑ Dixon 2011, p. 15.

- ↑ Dixon 1980, p. 70.

- 1 2 Tindale 1974, p. 193.

- ↑ Smith, Burke & Riley 2006, p. 1.

- 1 2 Connor 2002, p. 22.

- ↑ Connor 2002, pp. 2,22.

- ↑ Connor 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ Attenbrow 2010b, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Burke & Riley 2006.

- ↑ Smith 2009, pp. 1–110.

- ↑ Smith 2009, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Tindale 1974, p. 128.

- ↑ Foley 2007, pp. 178–179.

- ↑ Tindale 1974, p. 127.

- ↑ Foley 2007, p. 180.

- ↑ Connor 2002, p. 3.

- ↑ Smith 2005, pp. 1–6.

- ↑ Broome 2010, p. 16.

- ↑ Broome 2010, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Hinkson 2002, p. 65.

- ↑ Warren 2014b, p. 7.

- ↑ Fullagar 2015, p. 35.

- ↑ Smith 2009, p. 12.

- ↑ Barnes 2009, p. 151.

- 1 2 Attenbrow 2010b, p. 21.

- ↑ King 1986, p. 49.

- ↑ King 1986, p. 54.

- ↑ Warren 2014a.

- ↑ Warren 2014b, p. 73.

- ↑ King 1986, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Fullagar 2015, p. 36.

- ↑ King 1986, p. 50.

- ↑ Hinkson 2002, p. 70.

- ↑ Meacham 2010.

- ↑ Smith 2011.

- ↑ Dosen et al. 2013, p. 363.

- ↑ Warren 2014b, p. 74.

- ↑ King 1986, p. 48.

- ↑ Smith 2009, p. 9.

- ↑ Smith 2009, p. 11.

Sources

- Attenbrow, Val (2010a). Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records. Sydney: UNSW Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-1-74223-116-7.

- Attenbrow, Val (2010b). Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records. University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-742-23116-7.

- Barnes, Robert Winstanley (2009). An Unlikely Leader: The Life and Times of Captain John Hunter. Sydney University Press. ISBN 978-1-920-89919-6.

- Broome, Richard (2010). Aboriginal Australians: A History Since 1788. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-741-76554-0.

- Collins, David (1798). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales. London: T.Cadell, W. Davies.

- Connor, John (2002). The Australian Frontier Wars, 1788-1838. University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-868-40756-2.

- Dawes, William. "The Aboriginal language of Sydney". Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Project, SOAS, Aboriginal Affairs NSW.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1980). The Languages of Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29450-8.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2011). Searching for Aboriginal Languages: Memoirs of a Field Worker. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-02504-1.

- Dosen, Anthony; Ballantyne, Tanya; Brumpton, Marcia; Gibson, Kim; Harris, Leon; Lippingwell, Stephen (2013). Investigating Legal Studies for Queensland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-65346-7.

- Foley, Dennis (2007). "Leadership: the quandary of Aboriginal societies in crises, 1788 – 1830, and 1966". In Macfarlane, Ingereth; Hannah, Mark. Transgressions: Critical Australian Indigenous histories. Australian National University Press. pp. 177–192. ISBN 978-1-921-31344-8. JSTOR j.ctt24hfb0.12.

- Fullagar, Kate (2015). "From Pawns to Players: Rewriting the Lives of Three Indigenous Go-Betweens". In Jackson, Will; Manktelow, Emily. Subverting Empire: Deviance and Disorder in the British Colonial World. Springer. pp. 22–42. ISBN 978-1-137-46587-0.

- Heiss, Anita; Gibson, Melodie-Jane (2013). Aboriginal people and place. Barani: Sydney's Aboriginal History.

- Hinkson, Melinda (2002). "Exploring 'Aboriginal' sites in Sydney: a shifting politics of place?". Aboriginal History. 26: 62–77. JSTOR 24046048.

- King, Robert J. (1986). "Eora and English at Port Jackson: A Spanish View" (PDF). Aboriginal History. 10 (1): 47–58.

- Macey, Richard (2007). "Settlers' history rewritten: go back 30,000 years". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- Meacham, Steve (20 September 2010). "Right back at us: Bennelong's song for 1793 London". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Smith, Keith Vincent (2005). "Tupaia's Sketchbook" (PDF). eBLJ. pp. 1–6.

- Smith, Keith Vincent; Burke, Anthony; Riley, Michael (June 2006). EORA: Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770-1850 (PDF). State Library of New South Wales. ISBN 0 7313 71615.

- Smith, Keith Vincent (2009). "Bennelong among his people". Aboriginal History. 33: 7–30. JSTOR 24046821.

- Smith, Keith Vincent (2011). "1793: A Song of the Natives of New South Wales" (PDF). eBLJ. pp. 1–7.

- Stockton, Eugene D.; Nanson, Gerald C. (April 2004). "Cranebrook Terrace Revisited". Archaeology in Oceania. 39 (1): 59–60. JSTOR 40387277.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Eora (NSW)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University.

- Troy, Jakelin (1992). "The Sydney Language Notebooks and responses to language contact in early colonial NSW" (PDF). Australian Journal of Linguistics. 12 (1): 145–170.

- Warren, Chris (17 April 2014a). "Was Sydney's smallpox outbreak of 1789 an act of biological warfare against Aboriginal tribes?". ABC News.

- Warren, Christopher (2014b). "Smallpox at Sydney Cove – who, when, why?". Journal of Australian Studies. 38 (1): 68–86.

Further reading

- Kurupt, Daniel, ed. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia. Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 0-85575-234-3.

- Thieberger, N; McGregor junior, W (eds.). "Sydney language". Macquarie Aboriginal Words.