Dunghutti

| Dunghutti people | |

|---|---|

| aka: Dhangadi, Boorkutti, Burgadi, Burugardi, Dainggati, Dainiguid, Dang-getti, Dangadi, Dangati, Danggadi, Danggetti, Danghetti, Dhangatty, Djaingadi, Nulla Nulla, Tang-gette, Tangetti, and Thangatti[1] | |

| |

| Hierarchy | |

| Language family: | Pama–Nyungan |

| Language branch: | Yuin–Kuric |

| Language group: | Yora |

| Group dialects: | Dunghutti[2] |

| Area | |

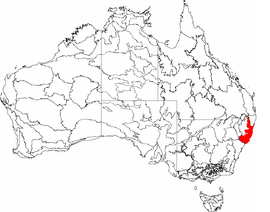

| Location: | Mid North Coast, New South Wales |

| Rivers | |

| Urban areas | |

| Notable individuals | |

The Dunghutti are an Aboriginal group whose traditional lands lie in the Macleay Valley, which extends from the eastern extremity at the Mid North Coast to the Northern Tablelands.[3] area.

Country

Norman Tindale estimated Dunghutti traditional lands to have encompassed some 3,500 square miles (9,100 km2). They took in the area from Point Lookout southwards as far as the headwaters of the MacLeay River and the vicinity of the Mount Royal Range. To the east, their territory ran as far as the crests of the coastal ranges, while their inland extension to the west ran up to the Great Dividing Range and Walcha.[1] The people to their north were the Gumbaynggirr. On their western flank were the Anēwan. The southern linguistic border is with Biripi.

History

An Aboriginal presence in the Dunghutti lands has been attested archaeologically to go back at least 4,000 years, according to the analysis of the materials excavated at the Clybucca midden, a site which the modern-day descendants of the Dunghutti and Gumbaynggirr claim territory. In the Clybucca area are ancient camp sites with shell beds in the form of mounds which are up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) high.[4]

Food was plentiful especially in the lower Macleay. Climate accounted for movement. The people in the colder climates of the upper Macleay could easily move into warmer places on the floor of the valley during winter. There are significant sites remaining in the Dunghutti land away from ground which has been cultivated. Stone implements have been found which give evidence of antiquity. Spears, boomerangs, shields, digging sticks, water and food carriers have been collected. In the colder areas cloaks were made from possum skins. Sacred sites were marked with carved trees and stone arrangements.

.jpg)

Gatherings took place to celebrate ceremonies to mark special events in the lives of the people. The last great gathering took place towards the end of the nineteenth century. Other language groups from north and south of the Macleay gathered near Smoky Range not long before the last marked tree was cut down and taken to the Australian Museum for preservation. Dunghutti people were hunters and gathers, a group who shared a common language and who organised themselves into smaller groups regularly living together. They lived in harmony with the land and their pattern of life was governed by codes of conduct regarded as sacred, having been handed down through countless generations. Remnants of the ancient culture remain in Macleay valley — middens and a fish trap in the Limeburners Creek Nature Reserve and a Bora Ring at Richardsons Crossing just north of Crescent Head. Along the creeks and on the tablelands there are artefact scatters, scarred trees and axe-grinding grooves. Archaeological sites include burial sites at East Kunderang mythological sites include the landscape of the upper Apsley Gorge; and contact sites encompass the rugged falls country where Dunghutti people staged their final fight against white settlers, as well as sites along Kunderang Brook where brutal massacres took place.

Dunghutti traditional foods

Aboriginal diet in the Macleay region including the heart of the cabbage palm, a tuber known as tow wack, and fern roots, a large sort of yam or sweet potato obtained from a small creeper the roots of which penetrate to a considerable depth in the alluvial soil. The Macleay River and the tidal creeks supplied fruits and fish, but due to the dense growth of rainforest in these areas, these areas were generally not suitable for camping unless cleared. Fish and shellfish from the estuaries and from the beaches, clams, oysters, cockles, large eels, a small kind of lobster and fresh-water mussels at all times procurable, whilst large crayfish and crabs are caught among the rocks. The adjacent dunes provided pigface and other edible plants, as well as grasses for grazing kangaroos, wallabies, snakes and lizards, as well as worms, grubs and birds used for food.

Dunghutti tribes

The four main tribes of the Dunghutti people are the Dangaddi, Daingatti, Thungutti and Djunghatti people with all four having smaller sub-groups (clans). They all lived in groups of average from eighty to a hundred men and women, exclusive of children, but the whole body of the tribe never united on the same spot, unless on some important occasion they were more generally divided into small parties, Man, women and children often detached companies roamed over any part of the country within the prescribed limits of the main tribe to which they belong.

Dunghutti dreaming

The common core of Aboriginal spirituality that exists in groups across the whole of Australia is the philosophy out of which values, ethics, protocols, behaviours and all social, political and economic organisation is developed. The basis of this philosophy is the idea of creation, the time when powerful creator spirits or spirit ancestors made sense out of chaos and produced the life forms and landscapes as we know them, and then sometimes lay down to rest or took to the sky. Many non-Aboriginal writers and some Aboriginal people have recorded these creation stories from different parts of the country over time. These stories are often characterised as the Dreaming and, as with Spirituality, the English words are not equivalent to the meaning that exists in Aboriginal languages for the basis of the philosophy, and for the Spirituality that is encompassed within it.

Dunghutti gods

The stories of the sky gods, including Baiame, have different names for these creation ancestors in different areas, and sometimes the stories differ according to the beliefs of people in specific places. For the people on the adjoining mid-north coast—Biripi, Dunghutti, and Gumbaynggirr. The specificities of these stories is more than can be covered here but it is fair to say that they encompass a similar script. Before life as we know it as human beings, there was a complex chaotic mass of matter that included these powerful beings. They were so powerful that they were able to change form and shape the chaos into form. They developed order and life out of the chaos by filling it with their activity and power. In intense bursts of activity, they were able to transform and develop formless matter into a landscape. The features of the land they brought into being hold in their names the stories of their own creation. And the ancestors in the same way gave rise to living forms, the animal species, all manner of plants, the landforms, watercourses (which, though inanimate, are understood to have their own spirit or being) and, of course, people. Each person or specific plant or place is linked to the spirit of its creation and thus to each other. This is a relationship of mutual spirit being, often referred to as totemism.

The period of intense creativity was as yet without law or morality, as different totemic ancestors in their travels and exploits negotiated, experimented, tested the options until they were finally closed and the boundaries were set for the living and the acting of the descent line. So the ancestral spirits gave to each living form its own Law, fixed for all time and written on the landscape. Some of these ancestral beings were culture heroes who taught humans how to hunt, to make fire and utensils, to perform ceremony and all that was important for survival. At length, after completing their tasks and overcome by weariness, they sank back into their original slumber. Some vanished into the ground whence they first emerged, others turned into the physical features of the landscape, leaving behind a trail of their life, the spirit-children yet to be born in the form of their ancestor. Though immobilized, these creator spirits did not cease to be alive, powerful and conscious. This creative activity continues through the life-force latent in their resting place, in sites of significance for their story and in their various transformations—not only specific landmarks but sacred objects of many kinds, totemic emblems, images, participants in ceremony and especially in their (human) totemic descendants

Long Gully

Long Gully Aboriginal Place was a ceremonial site. Long Gully was a passing out parade ground used in the latter stages of initiations by the Thungetti tribe on the mid-north coast of NSW. The ground is hidden by two high ridges, where ceremonies could be held privately. The last initiation ceremony held here was in 1932. In 1979, when the site was declared an Aboriginal Place, several men who were initiated here were still alive and actively sought protection for the site. These men ensured that knowledge of the site and its importance was passed on to younger generations within the Aboriginal community.

Carrai waterholes

It is a spiritual place for the local Aboriginal people. Young men of the Thungutti tribe went through initiation rites at Carrai Waterholes. It is a sacred men's site, and according to traditional Aboriginal law, access to the site and close knowledge of it is restricted to senior initiated men. The depth of the waterholes is a mystery. There is said to be a passage between the waterholes about 7 metres (23 ft) below the surface. The unusual formation of the waterholes and their unknown depth enhances their spiritual nature. Aboriginal children were warned not to go near the waterholes, both because of their sacred nature and their unknown depth.

Burrel Bulai

Burrel Bulai (Mount Anderson) is considered to be one of the most powerful sacred sites in Thunghutti/Dunghutti Country. It has special significance to local Aboriginal people because it is a place where 'clever-people' would prepare for specialised initiations. The mountain also has importance because it lies at the centre of Thunghutti/Dunghutti Country and has strong powers capable of drawing home local Aboriginal people. Burrel Bulai was recorded as a place of significance by Ray Kelly, an Aboriginal Research Officer with the NSW Sites of Significance Survey team. Ray Kelly documented stories told to him by initiated men at Bellbrook Mission about the importance and power of Burrel Bulai.[5]

Dendroglyphs

Dendroglyph or carved ceremonial trees. Dendroglyphs are the only examples of massive carvings in Aboriginal art. Symbolic designs, usually geometric, were carved on the living trees with axes and touched up from time to time to prevent the bark growing over the pattern and obliterating it. They were associated with initiation ceremonies and burial rights. Designs have a mythological significance, belonging to a totemic clan, local group or tribe. They are limited to New South Wales and some parts of southern Queensland.

Rainbow Serpent

Dunghutti people tell the story of how the Rainbow Serpent created the gorge at Apsley Falls in the Dreamtime. Take a walk to one of the viewing platforms and you may see a rainbow in the mist of the falling water. The Rainbow Serpent is said to travel underground from the base of the falls to reappear at the mill hole near Walcha on the Apsley River, 20 kilometres (12 mi) upstream. The site is marked at Walcha a mosaic made with the ideas and help of the local Dhungutti community. Apsley Falls are in the Oxley Wild Rivers National Park, just off the Oxley Highway, 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of Walcha. The Rainbow Serpent mosaic in Walcha is opposite the end of Legge Street on Derby Street.

.jpg)

Totem

The Dunghutti people's totem is the praying mantis and black raven The totemic relationship requires that people must learn how to take responsibility for relationships with the species and the totemic site, or sacred site, in the landscape and connected to the totemic ancestor.

Dunghutti art and culture

The Dunghutti Language Group supports language learning as an ongoing activity in the Macleay Valley. Elders are currently taking lessons in the Certificate 1 course at Kempsey TAFE, as well as taking an active part in helping to shape the course with decisions about appropriate content, language development etc., and teaching Dunghutti language in schools. This course will be offered again in 2013 for younger Dunghutti adults, and a Certificate 2 course will be designed for a test run in 2014.

The Dunghutti-Ngaku Aboriginal Art gallery offers works for sale by a number of highly renowned Aboriginal artists who are represented in major public and private collections. Visitors to the gallery can also purchase works from emerging artists living and working in the region. The gallery is located next to the Visitor Information Centre in parkland on the south side of Kempsey in the Macleay Valley.

The Wigay Aboriginal Cultural Park, Kempsey is a place of natural beauty, where people come for walks, gatherings, education and to learn more about traditional plants and Dunghutti culture. The park contains displays in wetland, wet forest, woodland, rainforest and tropical plants of Australia on 2.75 hectares.

Native title

The first successful claim under the Native Title Act was made by Ms Mary-Lou Buck of the Dunghutti community. The Dunghutti Elders Council administers Indigenous-owned land within New South Wales on behalf of the Dunghutti people. The Dunghutti people's native title rights and interests were recognised in the Dunghutti People determination made in April 1997.

The claim leading to this determination was lodged in November 1994 by Mary-Lou Black on behalf of the Dunghutti People. This claim was successfully mediated and negotiated over three years leading to the Crescent Head Agreement. All parties agreed to recognise the native title rights of the Dunghutti People which includes the exclusive right to possession, occupation and enjoyment of the land. Where native title had been extinguished, the parties agreed upon an amount of compensation for that extinguishment.

In addition to the determination, the Dunghutti Elders Council also administers two shared responsibility agreements on behalf of the traditional owners relating to workplace training and youth training.

In 2010, the Dunghutti Elders Council received $6.1 million as compensation for 12.4 hectares (31 acres) of land at Crescent Head that has been used for residential development.

In 2014, the Dunghutti Elders Council investigated the possibility of a 'blanket land claim' The claim would potentially be for all vacant crown land in the Dunghutti tribal area which extends from the Oxley Wild Rivers National Park at the head of the Macleay River, north to Yarrapinni Mountain and south as far as Walcha.

Notable Dunghutti people

Boxers

- Dave Sands - NSW Middleweight, Australian Middleweight, Light-Heavyweight, Heavyweight & British Empire Middleweight Title's

- Clement Sands - NSW Welterweight Title's

- Alfred Sands - NSW & Australian Middleweight Title's

- Russell Sands - NSW Featherweight, Australian Featherweight Title's

- George Sands

- Percy Sands

Six brothers whose family name was "Ritchie" but who fought professionally under the name of "Sands"

- Hector Thompson - NSW lightweight, Australaian Super Lightweight & Commonwealth British Empire super lightweight Title's. Best Known In the International Boxing Arena for taking on Roberto Durán

- Russell Sands - Is the Nephew of the sands brothers. He was the NSW Light Middleweight, South Seas Light Middleweight, Australian Welterweight & Super Welterweight Champion.

- Renold Quinlan - International Boxing Organisation Super Middleweight Champion. He is ranked 46 in the International Boxing Organisation. As of February 2016

Rugby League Players

- Greg Inglis - South Sydney Rabbitohs & Melbourne Storms

- Albert Kelly - Hull Kingston Rovers, Parramatta Eels, Cronulla Sharks, Newcastle Knights & Gold Coast Titans

- Jonathan Wright - New Zealand Warriors, Cronulla-Sutherland Sharks, Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs & Parramatta Eels

- Beau Champion - Parramatta Eels, South Sydney Rabbitohs, Melbourne Storms & Gold Coast Titans

- James Roberts - Brisbane Broncos, Gold Coast Titans, South Sydney Rabbitohs & Penrith Panthers

- Amos Roberts - St George Illawarra, Penrith Panthers, Sydney Roosters & Wigan Warriors

- Tyrone Roberts-Davis - Gold Coast Titans

- Paul Davis - Balmain Tigers & represented the Australian Aboriginies side at the 1992 Pacific Cup

Other Notable Dunghutti people

- Garibaldi - Was a Dunghutti Warrior, who fought valiantly from the ranges in what is now the Oxley Wild Rivers National Park, but was murdered with all his family in an ambush whilst they slept, in a dawn massacre. Garibaldi Rock now towers above the site where Garibaldi died at the Oxley Wild Rivers National Park.

- Mary-lou Buck - Passionately known as (aunty Mary-lou) signed the first successful Aboriginal native title claim for the Dunghutti People.

- Samantha Harris - Is an Australian fashion model, Harris featured prominently during Australian Fashion Week 2010 where she appeared in a record number of shows. She also appeared in a photoshoot for the label Miu Miu in the March 2010 edition of Australian Vogue, and featured on the June 2010 cover of the same magazine. In January 2011, Harris was named a "young women's fashion ambassador" for Australian department store, David Jones. Along with Miranda Kerr and Megan Gale, Harris was part of the store's television and print campaign for the Spring/Summer 2011/12 season. Samantha Harris Mother was a part of the Stolen Generation.

- Darlene Johnson - Started her writer/director career with the 1996 short film Two Bob Mermaid and continued exploring themes of race, identity and perception mainly in documentaries from International EMMY Award-nominated Stolen Generations to Stranger in my Skin and the "making-of" Phillip Noyce's Rabbit-Proof Fence. Ten years later, Johnson made her second short, Crocodile Dreaming, and then made River of No Return, a documentary about the complexities of living in a remote Indigenous community in Northern Australia. She has produced documentaries for ABC-TV's Message Stick series and is writing Bluey as part of the Screen Australia Springboard initiative.

- Loretta Kelly - Australian Aboriginal law academic, lecturer at Southern Cross University

- Amos Morris - He won a Golden Guitar Award in 2008 for Bush Ballad of the Year, becoming the youngest ever winner of the category. He has performed with John Williamson and Warren H Williams in the song "Australia is Another Word for Free" which won a Golden Guitar Award for Bush Ballad of the Year in 2009.

European contact and settlement

Dunghutti people were affected by government policy, through resistance to colonial process, suffered massacres by settlers and police, were incorporated into economy through clearing bush and stock work, segregated into reserves at Bellbrook, Burnt Bridge & Greenhill by Aboriginal Protection Board, followed by assimilation policies of Aboriginal Welfare Board.

History of Contact

The first known contact of any sort was Captain Cook when he passed it on 13 May 1770, writing in Cooks journal ("a point or headland, on which were fires that Caused a great Quantity of smook, which occasioned my giving it the name of Smooky Cape"). Smook was his usual spelling of smoke, the spelling for the cape now follows the modern spelling. The hills there were an important meeting place for Dunghutti people, it's possible Cook saw fires from such a gathering.[6]

At South West Rocks Trial Bay the brig Trial which was wrecked there in 1816 after it had been stolen by convicts who were attempting to escape to south-east Asia. When Captain Thomas Whyte found the wreck in 1817 there was no trace of the convicts and it was assumed they had all died by either starvation or being killed by the Dunghutti people.

In 1820 by John Oxley with Captain Allman, to make a survey of Port Macquarie and report on its suitability as a new settlement for convicts. Oxley was directed to examine in lets north of Smoky Cape. Sailing in the Prince Regent, Oxley entered the Macleay River but found only ten to twelve feet of water over the bar at high tide.

John Oxley who was the first European through the area when he passed near the Apsley Falls in September 1818. Major Archibald Clunes Innes, Commandant of Port Macquarie Penal Settlement, sent the first government gangs to penetrate the remote and inaccessible gorges and valleys in search of Australian red cedar (Toona ciliata) in c.1827. The cedar logs were hauled from the hillsides and floated down-river to Kempsey for loading on ships bound for Sydney. The cedar cutters were soon followed by pioneer cattle graziers who took up Crown leases to start properties such as Kunderang and Toorooka.

European settlement

Was recorded in 1827 when Captain A.C. Innes, the commandant at Port Macquarie, established a cedar party north of Euroka Creek on the Macleay River. The first land grants were surveyed on the east bank of the Macleay in 1835. Samuel Onions grant of 802 acres was sold to Enoch William Rudder, a merchant from Birmingham who became Kempsey's first white settler. He surveyed the land for a private town which he named Kempsey as he found the countryside reminiscent of the valley of Kempsey in Worcestershire, England. Rudder Park, in East Kempsey, is the site of this first settler's home.

1835 The Dunghutti people was confined to 40 hectares of land on the Bellwood Reserve, near present-day Kempsey. They previously owned 250,000 hectares,

John Oxley who was the first European through the area when he passed near the Apsley Falls in September 1818. Major Archibald Clunes Innes, Commandant of Port Macquarie Pen

1841 Clement Hodgkinson explored the upper reaches of the Macleay Valley.

For the Dunghutti, Anaiwan and Biripi, the Great Eastern Ranges became a last refuge and a base for a desperate resistance to the loss of their traditional lands and way of life. For 25 years they fought an intermittent guerilla war, emerging from the rugged ranges and gorges in planned sorties, to scare off Sheep and fight the shepherds and stockmen encroaching on their land. Reprisals were severe and indiscriminate with over 20 massacres of Aboriginal people occurred throughout the Hastings, Manning and Macleay ranges over that period, usually including the deaths of women and children. On occasion the landscape bears the names of some of the slain, in spite of efforts to deny and forget, and some brave leaders are still remembered.

1860s The Dunghutti resistance was brought to an end. Members of Dunghutti nations were gradually moved on to reserves & missions, with the Birpai moved away from the Hastings River to the north and south. However they took knowledge with them, maintained their identity and survived, despite the odds stacked against them.

For much of the 19th century, following European settlement in the Macleay Valley region, Dunghutti people continued moving throughout the landscape with small groups settling at camp sites on the outskirts of European settlements for brief periods, then moving on again.

Areas such as Pelican Island and the two Fattorini Islands in the Macleay River near Kempsey were reserved specifically for Aboriginal communities and were regarded as refuges where large numbers of Dunghutti people could live relatively undisturbed (Neil 1972).[7]

Farming on Fattorini Islands During the late 1800s, several Dunghutti families occupied Shark, Pelican and Fattorini islands. They cleared the land and cultivated corn.

The islands formed part of an unsupervised Aboriginal reserve that had been gazetted in 1885. By 1919 the islands were being farmed so efficiently that the Aborigines Protection Board Inspector advised against the islands' revocation.

However, in 1924 the Board decided that the residents on Fattorini Island would be relocated to nearby Pelican Island, and Fattorini Island's status as an Aboriginal reserve would be revoked. Later, Pelican Island's status was also revoked.

Many Aboriginal families from all three islands were forced to move to Kinchela Creek Station (Goodall 1996).

The Aborigines Protection Board's revocation of the island reserves and the flooding of the river both before and after the Fattorini Island's revocation forced more Aboriginal families to move off the islands.

The Aboriginal fringe camps at Green Hills was the major unofficial camp in the Macleay Valley. The Green Hills Dunghutti community survived a number of attempts by the Aborigines Protection Board to have it removed. During 1925, the Board and Kempsey Council tried on a number of occasions to force the 120 Aboriginal people to move off the land by issuing eviction and removal orders delivered by the police. At the same time, the community defied the Board's inspectors who were attempting to remove Aboriginal children to government institutions.

Following several failed attempts from the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) and other groups to secure adequate land tenure for families at the camp, the Aborigines Protection Board moved the community from Green Hills, putting them under the control of the white manager at Burnt Bridge Reserve (Goodall 1996).

The impact of assimilation on the State education system in Kempsey eventually allowed the first Aboriginal pupils to attend Green Hill Public School in 1947. But, when white parents moved their children from Green Hill school and sent them to West Kempsey, the school became all-Aboriginal, Although policies of assimilation had eventually allowed Aboriginal children to attend public schools in the Kempsey area, Aboriginal children were still forcibly removed from their families.

In February 1965 The Freedom Ride as it came to be called covered 2300 kilometres of northwest and coastal New South Wales highlighting racial discrimination. The Freedom ride demonstrated at Kempsey swimming pool.

In 1967, when the nation voted overwhelmingly to count Aboriginals as part of the Australian population. Nationally, the 90.77 per cent yes vote was the highest in favour of a referendum question in our history. Kempsey voted 68 per cent yes (Australian Electoral Commission).

See also

Notes

Citations

- 1 2 Tindale 1974, p. 192.

- ↑ AIATSIS 2012.

- ↑ NSW Government 2016.

- ↑ Clybucca 2007, pp. 1,3,6.

- ↑ NSWOoE&H 2013.

- ↑ NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service.

- ↑ South West Rocks.

Sources

- "Burrel Bulai". New South Wales Office of Environment & Heritage. 21 May 2013.

- "Clybucca Historic Site: Plan of Management" (PDF). NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. September 2007.

- "Language information: Dunghutti". Australian Indigenous Languages Database. AIATSIS. 26 June 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- "Smoky Cape Lighthouse Hat Head National Park". NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "South West Rocks".

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Dainggati (NSW)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University.

- "Yarriabini National Park". NSW Government. 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2017.