E-book

| Part of a series on |

| E-commerce |

|---|

| Online goods and services |

| Retail services |

| Marketplace services |

| Mobile commerce |

| Customer service |

| E-procurement |

| Purchase-to-pay |

An electronic book (or e-book or eBook) is a book publication made available in digital form, consisting of text, images, or both, readable on the flat-panel display of computers or other electronic devices.[1] Although sometimes defined as "an electronic version of a printed book",[2] some e-books exist without a printed equivalent. E-books can be read on dedicated e-reader devices, but also on any computer device that features a controllable viewing screen, including desktop computers, laptops, tablets and smartphones.

In the 2000s, there was a trend of print and e-book sales moving to the Internet, where readers buy traditional paper books and e-books on websites using e-commerce systems. With print books, readers are increasingly browsing through images of the covers of books on publisher or bookstore websites and selecting and ordering titles online; the paper books are then delivered to the reader by mail or another delivery service. With e-books, users can browse through titles online, and then when they select and order titles, the e-book can be sent to them online or the user can download the e-book.[3] At the start of 2012 in the U.S., more e-books were published online than were distributed in hardcover.[4]

The main reasons for people buying e-books online are possibly lower prices, increased comfort (as they can buy from home or on the go with mobile devices) and a larger selection of titles.[5] With e-books, "[e]lectronic bookmarks make referencing easier, and e-book readers may allow the user to annotate pages." [6] "Although fiction and non-fiction books come in e-book formats, technical material is especially suited for e-book delivery because it can be [electronically] searched" for keywords. In addition, for programming books, code examples can be copied.[6] The amount of e-book reading is increasing in the U.S.; by 2014, 28% of adults had read an e-book, compared to 23% in 2013. This is increasing, because by 2014 50% of American adults had an e-reader or a tablet, compared to 30% owning such devices in 2013.[7]

Terminology

E-books are also referred to as "ebooks", "eBooks", "Ebooks", "e-Books", "e-journals", "e-editions" or as "digital books". The devices that are designed specifically for reading e-books are called "e-readers", "ebook device" or "eReaders".

History

The Readies (1930)

Some trace the idea of an e-reader that would enable a reader to view books on a screen to a 1930 manifesto by Bob Brown, written after watching his first "talkie" (movie with sound). He titled it The Readies, playing off the idea of the "talkie".[8] In his book, Brown says movies have outmaneuvered the book by creating the "talkies" and, as a result, reading should find a new medium:

“A simple reading machine which I can carry or move around, attach to any old electric light plug and read hundred-thousand-word novels in 10 minutes if I want to, and I want to.”

Brown's notion, however, was much more focused on reforming orthography and vocabulary, than on medium (“It is time to pull out the stopper” and begin “a bloody revolution of the word.”): introducing huge numbers of portmanteau symbols to replace normal words, and punctuation to simulate action or movement; so it is not clear whether this fits in the history of "e-books" or not. Later e-readers never followed a model at all like Brown's. Nevertheless, Brown predicted the miniaturization and portability of e-readers. In an article, Jennifer Schuessler writes, "The machine, Brown argued, would allow readers to adjust the type size, avoid paper cuts and save trees, all while hastening the day when words could be 'recorded directly on the palpitating ether.'"[9] He felt the e-reader (and his notions for changing text itself) should bring a completely new life to reading. Schuessler relates it to a DJ spinning bits of old songs to create a beat or an entirely new song as opposed to just a remix of a familiar song.[9]

Inventor

The inventor of the first e-book is not widely agreed upon. Some notable candidates include the following:

Ángela Ruiz Robles (1949)

In 1949, Ángela Ruiz Robles, a teacher from León, Spain, patented the Enciclopedia Mecánica, or the Mechanical Encyclopedia, a mechanical device which operated on compressed air where text and graphics were contained on spools that users would load onto rotating spindles. Her idea was to create a device which would decrease the number of books that her pupils carried to school. The final device would include audio recordings, a magnifying glass, a calculator and an electric light for night reading.[10] Her device was never put into production but one of her prototypes is kept in the National Museum of Science and Technology in La Coruna, Spain.[11]

Roberto Busa (late 1949–1970)

The first e-book may be the Index Thomisticus, a heavily annotated electronic index to the works of Thomas Aquinas, prepared by Roberto Busa, S.J. beginning in 1949 and completed in the 1970s.[12] Although originally stored on a single computer, a distributable CD-ROM version appeared in 1989. However, this work is sometimes omitted; perhaps because the digitized text was a means for studying written texts and developing linguistic concordances, rather than as a published edition in its own right.[13] In 2005, the Index was published online.[14]

Doug Engelbart and Andries van Dam (1960s)

Alternatively, some historians consider electronic books to have started in the early 1960s, with the NLS project headed by Doug Engelbart at Stanford Research Institute (SRI), and the Hypertext Editing System and FRESS projects headed by Andries van Dam at Brown University.[15][16][17] FRESS documents ran on IBM mainframes and were structure-oriented rather than line-oriented; they were formatted dynamically for different users, display hardware, window sizes, and so on, as well as having automated tables of contents, indexes, and so on. All these systems also provided extensive hyperlinking, graphics, and other capabilities. Van Dam is generally thought to have coined the term "electronic book",[18][19] and it was established enough to use in an article title by 1985.[20]

FRESS was used for reading extensive primary texts online, as well as for annotation and online discussions in several courses, including English Poetry and Biochemistry. Brown's faculty made extensive use of FRESS; for example the philosopher Roderick Chisholm used it to produce several of his books. Thus in the Preface to Person and Object (1979) he writes "The book would not have been completed without the epoch-making File Retrieval and Editing System..."[21] Brown University's work in electronic book systems continued for many years, including US Navy funded projects for electronic repair-manuals;[22] a large-scale distributed hypermedia system known as InterMedia;[23] a spinoff company Electronic Book Technologies that built DynaText, the first SGML-based e-reader system; and the Scholarly Technology Group's extensive work on the Open eBook standard.

Michael S. Hart (1971)

Despite the extensive earlier history, several publications report Michael S. Hart as the inventor of the e-book.[24][25][26] In 1971, the operators of the Xerox Sigma V mainframe at the University of Illinois gave Hart extensive computer-time. Seeking a worthy use of this resource, he created his first electronic document by typing the United States Declaration of Independence into a computer in plain text.[27] Hart planned to create documents using plain text to make them as easy as possible to download and view on devices.

Early implementations

After Hart first adapted the Declaration of Independence into an electronic document in 1971, Project Gutenberg was launched to create electronic copies of more texts - especially books.[27] Another early e-book implementation was the desktop prototype for a proposed notebook computer, the Dynabook, in the 1970s at PARC: a general-purpose portable personal computer capable of displaying books for reading.[28] In 1980 the US Department of Defense began concept development for a portable electronic delivery device for technical maintenance information called project PEAM, the Portable Electronic Aid for Maintenance. Detailed specifications were completed in FY 82, and prototype development began with Texas Instruments that same year. Four prototypes were produced and delivered for testing in 1986. Tests were completed in 1987. The final summary report was produced by the US Army research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences in 1989 authored by Robert Wisher and J. Peter Kincaid.[29] A patent application for the PEAM device [30] was submitted by Texas Instruments titled "Apparatus for delivering procedural type instructions" was submitted Dec 4, 1985 listing John K. Harkins and Stephen H. Morriss as inventors.

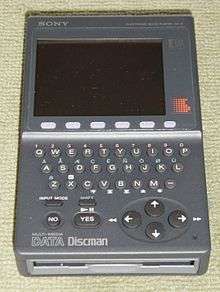

In 1992, Sony launched the Data Discman, an electronic book reader that could read e-books that were stored on CDs. One of the electronic publications that could be played on the Data Discman was called The Library of the Future.[31] Early e-books were generally written for specialty areas and a limited audience, meant to be read only by small and devoted interest groups. The scope of the subject matter of these e-books included technical manuals for hardware, manufacturing techniques, and other subjects. In the 1990s, the general availability of the Internet made transferring electronic files much easier, including e-books.

E-book formats

As e-book formats emerged and proliferated, some garnered support from major software companies, such as Adobe with its PDF format that was introduced in 1993.[32] Unlike most other formats, PDF documents are generally tied to a particular dimension and layout, rather than adjusting dynamically to the current page, window, or other size. Different e-reader devices followed different formats, most of them accepting books in only one or a few formats, thereby fragmenting the e-book market even more. Due to the exclusiveness and limited readerships of e-books, the fractured market of independent publishers and specialty authors lacked consensus regarding a standard for packaging and selling e-books.

Meanwhile, scholars formed the Text Encoding Initiative, which developed consensus guidelines for encoding books and other materials of scholarly interest for a variety of analytic uses as well as reading, and countless literary and other works have been developed using the TEI approach. In the late 1990s, a consortium formed to develop the Open eBook format as a way for authors and publishers to provide a single source-document which many book-reading software and hardware platforms could handle. Several scholars from the TEI were closely involved in the early development of Open eBook . Focused on portability, Open eBook as defined required subsets of XHTML and CSS; a set of multimedia formats (others could be used, but there must also be a fallback in one of the required formats), and an XML schema for a "manifest", to list the components of a given e-book, identify a table of contents, cover art, and so on. This format led to the open format EPUB. Google Books has converted many public domain works to this open format.[33]

In 2010, e-books continued to gain in their own specialist and underground markets. Many e-book publishers began distributing books that were in the public domain. At the same time, authors with books that were not accepted by publishers offered their works online so they could be seen by others. Unofficial (and occasionally unauthorized) catalogs of books became available on the web, and sites devoted to e-books began disseminating information about e-books to the public.[34] Nearly two-thirds of the U.S. Consumer e-book publishing market are controlled by the "Big Five". The "Big Five" publishers include: Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster.[35]

Libraries

US Libraries began providing free e-books to the public in 1998 through their websites and associated services,[36] although the e-books were primarily scholarly, technical or professional in nature, and could not be downloaded. In 2003, libraries began offering free downloadable popular fiction and non-fiction e-books to the public, launching an E-book lending model that worked much more successfully for public libraries.[37] The number of library e-book distributors and lending models continued to increase over the next few years. From 2005 to 2008 libraries experienced 60% growth in e-book collections.[38] In 2010, a Public Library Funding and Technology Access Study[39] found that 66% of public libraries in the US were offering e-books,[40] and a large movement in the library industry began seriously examining the issues related to lending e-books, acknowledging a tipping point of broad e-book usage.[41]

The US National Library of Medicine has for many years provided PubMed, a nearly-exhaustive bibliography of medical literature. In early 2000, NLM started PubMed Central, which provides full-text e-book versions of many medical journal articles and books, through cooperation with scholars and publishers in the field. Pubmed Central now provides archiving and access to over 4.1 million articles, maintained in a standard XML format known as the Journal Article Tag Suite (or "JATS").

However, some publishers and authors have not endorsed the concept of electronic publishing, citing issues with user demand, copyright piracy and challenges with proprietary devices and systems.[42] In a survey of interlibrary loan librarians it was found that 92% of libraries held e-books in their collections and that 27% of those libraries had negotiated interlibrary loan rights for some of their e-books. This survey found significant barriers to conducting interlibrary loan for e-books.[43] Demand-driven acquisition (DDA) has been around for a few years in public libraries, which allows vendors to streamline the acquisition process by offering to match a library's selection profile to the vendor's e-book titles.[44] The library's catalog is then populated with records for all the e-books that match the profile.[44] The decision to purchase the title is left to the patrons, although the library can set purchasing conditions such as a maximum price and purchasing caps so that the dedicated funds are spent according to the library's budget.[44] The 2012 meeting of the Association of American University Presses included a panel on patron-drive acquisition (PDA) of books produced by university presses based on a preliminary report by Joseph Esposito, a digital publishing consultant who has studied the implications of PDA with a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.[45]

Challenges

Although the demand for e-book services in libraries has grown in the decades of the 2000s and 2010s, difficulties keep libraries from providing some e-books to clients.[46] Publishers will sell e-books to libraries, but they only give libraries a limited license to the title in most cases. This means the library does not own the electronic text but that they can circulate it either for a certain period of time or for a certain number of check outs, or both. When a library purchases an e-book license, the cost is at least three times what it would be for a personal consumer.[46] E-book licenses are more expensive than paper-format editions because publishers are concerned that an e-book that is sold could theoretically be read and/or checked out by a huge number of users, which could adversely affect sales. However, some studies have found the opposite effect (for example, Hilton and Wikey 2010)[47]

Archival storage

The Internet Archive and Open Library offer more than six million fully accessible public domain e-books. Project Gutenberg has over 52,000 freely available public domain e-books.

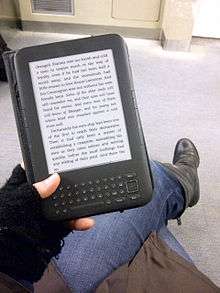

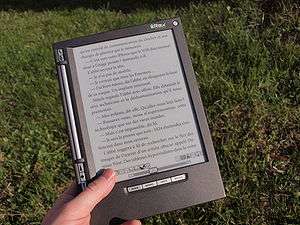

Dedicated hardware readers and mobile software

An e-reader, also called an e-book reader or e-book device, is a mobile electronic device that is designed primarily for the purpose of reading e-books and digital periodicals. An e-reader is similar in form, but more limited in purpose than a tablet. In comparison to tablets, many e-readers are better than tablets for reading because they are more portable, have better readability in sunlight and have longer battery life.[48] In July 2010, online bookseller Amazon.com reported sales of e-books for its proprietary Kindle outnumbered sales of hardcover books for the first time ever during the second quarter of 2010, saying it sold 140 e-books for every 100 hardcover books, including hardcovers for which there was no digital edition.[49] By January 2011, e-book sales at Amazon had surpassed its paperback sales.[50] In the overall US market, paperback book sales are still much larger than either hardcover or e-book; the American Publishing Association estimated e-books represented 8.5% of sales as of mid-2010, up from 3% a year before.[51] At the end of the first quarter of 2012, e-book sales in the United States surpassed hardcover book sales for the first time.[4]

Until late 2013, use of an e-reader was not allowed on airplanes during takeoff and landing by the FAA.[52] In November 2013, the FAA allowed use of e-readers on airplanes at all times if it is in Airplane Mode, which means all radios turned off, and Europe followed this guidance the next month.[53] In 2014, The New York Times predicted that by 2018 e-books will make up over 50% of total consumer publishing revenue in the United States and Great Britain.[54]

Applications

Some of the major book retailers and multiple third-party developers offer free (and in some third-party cases, premium paid) e-reader software applications (apps) for the Mac and PC computers as well as for Android, Blackberry, iPad, iPhone, Windows Phone and Palm OS devices to allow the reading of e-books and other documents independently of dedicated e-book devices. Examples are apps for the Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble Nook, iBooks, Kobo eReader and Sony Reader.

Timeline

Until 1979

- ~1949

- Ángela Ruiz Robles patented in Galicia, Spain, the idea of the electronic book, called the Mechanical Encyclopedia.

- Roberto Busa begins planning the Index Thomisticus.[13]

- ~1963

- Doug Engelbart starts the NLS (and later Augment) projects.[15]

- ~1965

- Andries van Dam starts the HES (and later FRESS) projects, with assistance from Ted Nelson, to develop and use electronic textbooks for humanities and in pedagogy.[16][17]

- 1971

- Michael S. Hart types the US Declaration of Independence into a computer to create the first e-book available on the Internet and launches Project Gutenberg in order to create electronic copies of more books.[27]

- 1978

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy radio series launches (novel published in 1979), featuring an electronic reference book containing all knowledge in the Galaxy. This vast amount of data could be fit into something the size of a large paperback book, with updates received over the "Sub-Etha".[55]

- ~1979

- Roberto Busa finishes the Index Thomisticus, a complete lemmatisation of the 56 printed volumes of Saint Thomas Aquinas and of a few related authors.[56]

1980–99

- 1986

- Judy Malloy wrote and programmed Uncle Roger, the first online hypertext fiction with links that took the narrative in different directions depending on the reader's choice.[57]

- 1989

- Project Gutenberg releases its 10th e-book to its website.

- Franklin Computer released an electronic edition of the Bible that was read on a stand-alone device.[58]

- 1990

- Eastgate Systems publishes the first hypertext fiction released on floppy disk, "Afternoon, a story", by Michael Joyce.[59]

- Electronic Book Technologies releases DynaText, the first SGML-based system for delivering large-scale books such as aircraft technical manuals. It was later tested on a US aircraft carrier as replacement for paper manuals.

- 1991

- Voyager Company develops Expanded Books, which are books on CD-ROM in a digital format.[60]

- 1992

The DD-8 Data Discman

The DD-8 Data Discman

- F. Crugnola and I. Rigamonti design and create the first e-reader, called Incipit, as a thesis project at the Polytechnic University of Milan.[61][62]

- Sony launches the Data Discman e-book player.[63]

- 1993

- Peter James published his novel Host on two floppy disks and at the time it was called the "world's first electronic novel"; a copy of it is stored at the Science Museum.[64]

- Hugo Award and Nebula Award nominee works are included on a CD-ROM by Brad Templeton.[65]

- Bibliobytes, a website for obtaining e-books, both for free and for sale on the Internet, launches.[66]

- 1994

- C & M Online is founded in Raleigh, North Carolina and publishes e-books through its imprint, Boson Books. Authors include Fred Chappell, Kelly Cherry, Leon Katz, Richard Popkin, and Robert Rodman.

- The popular format for publishing e-books changed from plain text to HTML.

- 1995

- Online poet Alexis Kirke discusses the need for wireless internet electronic paper readers in his article "The Emuse".[67]

- 1996

- Project Gutenberg reaches 1,000 titles.[68]

- Joseph Jacobson works at MIT to create electronic ink, a high-contrast, low-cost, read/write/erase medium to display e-books.[69]

- 1997

- E Ink Corporation is co-founded in 1997 by MIT undergraduates J.D. Albert, Barrett Comiskey, MIT professor Joseph Jacobson, as well as Jeremy Rubin and Russ Wilcox to create an electronic printing technology.[70] This technology is later used to on the displays of the Sony Reader, Barnes & Noble Nook, and Amazon Kindle.

- 1998

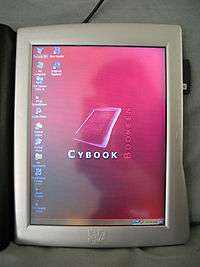

Bookeen's Cybook Gen1

Bookeen's Cybook Gen1

- NuvoMedia released the first handheld e-reader, the Rocket eBook.[71]

- SoftBook launched its SoftBook reader. This e-reader, with expandable storage, could store up to 100,000 pages of content, including text, graphics and pictures.[72]

- The Cybook was sold and manufactured at first by Cytale (1998–2003) and later by Bookeen.

- 1999

- The NIST released the Open eBook format based on XML to the public domain, most future e-book formats derive from Open eBook.[73] and on XML.

- Publisher Simon & Schuster created a new imprint called ibooks and became the first trade publisher to simultaneously to publish some of their titles in e-book and print format.

- Oxford University Press offered a selection of its books available as e-books through netLibrary.

- Publisher Baen Books opens up the Baen Free Library to make available Baen titles as free e-books.[74]

- Kim Blagg, via her company Books OnScreen, began selling multimedia-enhanced e-books on CDs through retailers including Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Borders Books.[75]

2000s

- 2000

- Joseph Jacobson, Barrett O. Comiskey and Jonathan D. Albert are granted US patents related to displaying electronic books, these patents are later used in the displays for most e-readers.[76]

- Stephen King releases his novella Riding the Bullet exclusively online and it became the first mass-market e-book, selling 500,000 copies in 48 hours.[77] In Spanish, Corín Tellado releases his novella Milagro en el camino also only online.[78]

- Microsoft releases the Microsoft Reader with ClearType for increased readability on PCs and handheld devices.[79]

- Microsoft and Amazon worked together to sell e-books that could be purchased on Amazon and using Microsoft software downloaded to PCs and handhelds.

- A digitized version of the Gutenberg Bible was made available online at the British Library.[80]

- 2001

- Adobe releases Adobe Acrobat Reader 5.0 allowing users to underline, take notes and bookmark.

- 2002

- Palm, Inc and OverDrive, Inc make Palm Reader e-books available worldwide and offered over 5,000 e-books in several languages; these could be read on Palm PDAs or using a computer application.[81]

- Random House and HarperCollins start to sell digital versions of their titles in English.

- 2004

- Sony Librie, first e-reader using an E Ink display was released; it had a six-inch screen.[82]

- Google announces plans to digitize the holdings of several major libraries,[83] as part of what would later be called the Google Books Library Project.

- 2005

- Amazon buys Mobipocket, the creator of the mobi e-book file format and e-reader software.[84]

- Google is sued for copyright infringement by the Authors Guild for scanning books still in copyright.[85]

- 2006

- Sony Reader PRS-500 with an E Ink screen and two weeks of battery life was released.[86]

- LibreDigital launched BookBrowse as an online reader for publisher content.

- 2007

The larger Kindle DX with a Kindle 2 for size comparison

The larger Kindle DX with a Kindle 2 for size comparison

- The International Digital Publishing Forum releases EPUB to replace Open eBook.[87]

- Amazon.com releases the Kindle e-reader with 6-inch E Ink screen in the US and it sells outs in 5.5 hours.[88]

- Simultaneously with the Kindle in November, the Kindle Store opened that initially had more than 88,000 e-books available.[88]

- Bookeen launches Cybook Gen3 in Europe, it could display e-books and play audiobooks.[89]

- 2008

- Adobe and Sony agree to share their technologies (Adobe Reader and DRM) with each other.

- Sony sells the Sony Reader PRS-505 in UK and France.

- BooksOnBoard becomes first retailer to sell e-books for iPhones.

- 2009

- Bookeen releases the Cybook Opus in the US and in Europe.

- Sony releases the Reader Pocket Edition and Reader Touch Edition.

- Amazon releases the Kindle 2 that included a text-to-speech feature.

- Amazon releases the Kindle DX that had a 9.7-inch screen in the US.

- Barnes & Noble releases the Nook e-reader in the US.

- Amazon released the Kindle for PC application in late 2009, making the Kindle Store library available for the first time outside Kindle hardware.[90]

2010s

- 2010

- In January 2010, Amazon releases the Kindle DX International Edition worldwide.[91]

- Bookeen reveals the Cybook Orizon at CES.[92]

- Apple releases the iPad bundled with an e-book app called iBooks.[93]

- Kobo Inc. releases its Kobo eReader to be sold at Indigo/Chapters in Canada and Borders in the U.S.

- Amazon reports that its e-book sales outnumbered sales of hardcover books for the first time ever during the second quarter of 2010.[49]

- Amazon releases the third generation Kindle, available in Wi-Fi and 3G & Wi-Fi versions.

- Kobo Inc. releases an updated Kobo eReader, which included Wi-Fi.

- Barnes & Noble releases the Nook Color, a color LCD tablet.

- Google launches Google eBooks offering over 3 million titles, becoming the world's largest e-book store at that time.[94]

- PocketBook expands its line with an Android e-reader.[95]

- In Canada, The Sentimentalists won the prestigious national Giller Prize in 2010. Owing to the small scale of the novel's independent publisher, the book was not widely available in printed form so the e-book edition became the top-selling title for Kobo devices that year.[96]

- 2011

- Amazon.com announces in May that its e-book sales in the US now exceed all of its printed book sales.[97]

- Barnes & Noble releases the Nook Simple Touch e-reader and Nook Tablet.[98]

- Bookeen launches its own e-books store, BookeenStore.com, and starts to sell digital versions of titles in French.[99]

- Nature Publishing publishes Principles of Biology, a customizable, modular textbook, with no corresponding paper edition.

- The e-reader market grows in Spain, and companies like Telefónica, Fnac, and Casa del Libro launches their e-readers with the Spanish brand "bq readers".

- Amazon launches the Kindle Fire and Kindle Touch; both devices were designed for e-reading.

- 2012

- E-books sold in the U.S. market collects over three billion in revenue.[100]

- Kbuuk released the cloud-based e-book self-publishing SaaS platform[101] on the Pubsoft digital publishing engine.

- Apple releases iBooks Author, software for creating iPad e-books to be directly published in its iBooks bookstore or to be shared as PDF files.[102]

- Apple opens a textbook section in its iBooks bookstore.[103]

- Library.nu - previously called ebooksclub.org and gigapedia.com, a popular linking website for downloading e-books - was accused of copyright infringement and shut down by court order on February 15.[104]

- The publishing companies Random House, Holtzbrinck, and arvato get an e-book library called Skoobe on the market.[105]

- US Department of Justice prepares anti-trust lawsuit against Apple, Simon & Schuster, Hachette Book Group, Penguin Group, Macmillan, and HarperCollins, alleging collusion to increase the price of books sold on Amazon.[106][107]

- PocketBook releases the PocketBook Touch, an E Ink Pearl e-reader, winning awards from German magazines Tablet PC and Computer Bild.[108][109]

- In September, Amazon releases the Kindle Paperwhite, its first e-reader with built-in front LED lights.

- 2013

- In April 2013, Barnes & Noble posts losses of $475 million on its Nook business for the prior fiscal year and in June announces its intention to discontinue manufacturing Nook tablets, although it plans to continue making and designing black-and-white e-readers such as the Nook Simple Touch, which "are more geared to serious readers, who are its customers, than to tablets".[110]

- The Association of American Publishers announces that e-books now account for about 20% of book sales. Barnes & Noble estimates it has a 27% share of the U.S. e-book market.[110]

- In June, Apple executive Keith Moerer testifies in the e-book price fixing trial that the iBookstore held approximately 20% of the e-book market share in the United States within the months after launch - a figure that Publishers Weekly reports is roughly double many of the previous estimates made by third parties. Moerer further testified that iBookstore acquired about an additional 20% by adding Random House in 2011.[111]

- Five major US e-book publishers, as part of their settlement of a price-fixing suit, were ordered to refund about $3 for every electronic copy of a New York Times best-seller that they sold from April 2010 to May 2012.[100] This could equal $160 million in settlement charges.

- Barnes & Noble releases the Nook Glowlight, which has a 6-inch touchscreen using E Ink Pearl and Regal, with built-in front LED lights.

- In April, Kobo released the Kobo Aura HD with a 6.8-inch screen, which is larger than the current models produced by its US competitors.[112]

- In May, Mofibo launched the first Scandinavian unlimited access e-book subscription service.[113]

- In July, US District Court Judge Denise Cote finds Apple guilty of conspiring to raise the retail price of e-books and schedules a trial in 2014 to determine damages.[114]

- In August, Kobo released the Kobo Aura, a baseline touchscreen six-inch e-reader.

- In September, Oyster launches its unlimited access e-book subscription service.[115]

- In November, US District Judge Chin sides with Google in Authors Guild v. Google, citing fair use.[116] The authors said they would appeal.[117]

- In December, Scribd launched the first public unlimited access subscription service for e-books.[118]

- 2014

- In early 2014, Amazon launches Kindle Unlimited as an unlimited-access e-book and audiobook subscription service.[119]

- In April, Kobo released the Aura H₂0, the world's first waterproof commercially produced e-reader.[120]

- In June, US District Court Judge Cote grants class action certification to plaintiffs in a lawsuit over Apple's alleged e-book price conspiracy; the plaintiffs are seeking $840 million in damages.[121] Apple appeals the decision.

- In June, Apple settles the e-book antitrust case that alleged Apple conspired to e-book price fixing out of court with the States; however if Judge Cote's ruling is overturned in appeal the settlement would be reversed.[122]

- 2015

- In June 2015, the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals with a 2-1 vote concurs with Judge Cote that Apple conspired to e-book price fixing and violated federal antitrust law.[123] Apple appealed the decision.

- In June, Amazon released the Kindle Paperwhite (3rd generation) that is the first e-reader to feature Bookerly, a font exclusively designed for e-readers.[124]

- In September, Oyster announced its unlimited access e-book subscription service would be shut down in early 2016 and that it would be acquired by Google.[125]

- In September, Malaysian e-book company, e-Sentral, introduced for the first time geo-location distribution technology for e-books via bluetooth beacon. It was first demonstrated in a large scale at Kuala Lumpur International Airport.[126]

- In October, Amazon releases the Kindle Voyage that has a 6-inch, 300 ppi E Ink Carta HD display, which was the highest resolution and contrast available in e-readers as of 2014.[127] It also features adaptive LED lights and page turn sensors on the sides of the device.

- In October, B&N released the Glowlight Plus, its first waterproof e-reader.[128]

- In October, the US appeals court sided with Google instead of the Authors' Guild, declaring that Google did not violate copyright law in its book scanning project.[129]

- In December, Playster launched an unlimited-access subscription service including e-books and audiobooks.[130]

- By the end of 2015, Google Books scanned more than 25 million books.[9]

- By 2015, over 70 million e-readers had been shipped worldwide.[9]

- 2016

- In March 2016, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to hear Apple's appeal that it conspired to e-book price fixing therefore the previous court decision stands, which means Apple must pay $450 million.[131]

- In April, the Supreme Court declined to hear the Authors Guild's appeal of its book scanning case that means the lower court's decision stands; this result means Google is allowed to scan library books and display snippets in search results without violating US copyright law.[132]

- In April, Amazon released the Kindle Oasis, its first e-reader in five years to have physical page turn buttons and as a premium product includes a leather case with a battery inside; the Oasis without including the case is the lightest e-reader on the market.[133]

- In August, Kobo released the Aura One, the first commercial e-reader with a 7.8-inch E Ink Carta HD display.[134]

- In September 2016, Perlego released an online platform that provides e-books to students under a monthly subscription fee in Europe.[135]

- By the end of 2016, smartphones and tablets both individually overtook e-readers for ways to read an e-book, and paperbook books sales were higher than e-book sales.[136]

- 2017

- In February 2017, the Association of American Publishers released data that shows the U.S. adult e-book market declined 16.9% in the first nine months of 2016 over the same time in 2015 and Nielsen Book determined that in 2016 the e-book market had an overall total decline of 16% in 2016 over 2015, including all age groups.[137] This decline is partly due to widespread e-book price increases by major publishers, which brought the average e-book price from $6 to nearly $10.[138]

- In March, The Guardian reported that sales of physical books outperform digital titles in the UK, since it can be cheaper to buy the physical version of a book when compared to the digital version due to Amazon's deal with publishers that allows agency pricing.[136]

- In April, it was reported that the 2016 sales of hardcover books were higher than e-books for the first time in five years.[138]

Formats

Writers and publishers have many formats to choose from when publishing e-books. Each format has advantages and disadvantages. The most popular e-readers[139] and their natively supported formats are shown below:

| Reader | Native e-book formats |

|---|---|

| Amazon Kindle and Fire tablets[140] | AZW, AZW3, KF8, non-DRM MOBI, PDF, PRC, TXT |

| Barnes & Noble Nook and Nook Tablet[141] | EPUB, PDF |

| Apple iPad[142] | EPUB, IBA (Multitouch books made via iBooks Author), PDF |

| Sony Reader[140] | EPUB, PDF, TXT, RTF, DOC, BBeB |

| Kobo eReader and Kobo Arc[143][144] | EPUB, PDF, TXT, RTF, HTML, CBR (comic), CBZ (comic) |

| PocketBook Reader and PocketBook Touch[145][146] | EPUB DRM, EPUB, PDF DRM, PDF, FB2, FB2.ZIP, TXT, DJVU, HTM, HTML, DOC, DOCX, RTF, CHM, TCR, PRC (MOBI) |

Digital rights management

Most e-book publishers do not warn their customers about the possible implications of the digital rights management tied to their products. Generally, they claim that digital rights management is meant to prevent illegal copying of the e-book. However, in many cases, it is also possible that digital rights management will result in the complete denial of access by the purchaser to the e-book.[147] The e-books sold by most major publishers and electronic retailers, which are Amazon.com, Google, Barnes & Noble, Kobo Inc. and Apple Inc., are DRM-protected and tied to the publisher's e-reader software or hardware. The first major publisher to omit DRM was Tor Books, one of the largest publishers of science fiction and fantasy, in 2012. Smaller e-book publishers such as O'Reilly Media, Carina Press and Baen Books had already forgone DRM previously.[148]

Production

Some e-books are produced simultaneously with the production of a printed format, as described in electronic publishing, though in many instances they may not be put on sale until later. Often, e-books are produced from pre-existing hard-copy books, generally by document scanning, sometimes with the use of robotic book scanners, having the technology to quickly scan books without damaging the original print edition. Scanning a book produces a set of image files, which may additionally be converted into text format by an OCR program.[149] Occasionally, as in some projects, an e-book may be produced by re-entering the text from a keyboard. Sometimes only the electronic version of a book is produced by the publisher. It is possible to release an e-book chapter by chapter as each chapter is written. This is useful in fields such as information technology where topics can change quickly in the months that it takes to write a typical book. It is also possible to convert an electronic book to a printed book by print on demand. However, these are exceptions as tradition dictates that a book be launched in the print format and later if the author wishes an electronic version is produced. The New York Times keeps a list of best-selling e-books, for both fiction[150] and non-fiction.[151]

Reading data

All of the e-readers and reading apps are capable of tracking e-book reading data, and the data could contain which e-books users open, how long the users spend reading each e-book and how much of each e-book is finished.[152] In December 2014, Kobo released e-book reading data collected from over 21 million of its users worldwide. Some of the results were that only 44.4% of UK readers finished the bestselling e-book The Goldfinch and the 2014 top selling e-book in the UK, "One Cold Night", was finished by 69% of readers; this is evidence that while popular e-books are being completely read, some e-books are only sampled.[153]

Comparison to printed books

Advantages

In the space that a comparably sized physical book takes up, an e-reader can contain thousands of e-books, limited only by its memory capacity. Depending on the device, an e-book may be readable in low light or even total darkness. Many e-readers have a built-in light source, can enlarge or change fonts, use text-to-speech software to read the text aloud for visually impaired, elderly or dyslexic people or just for convenience.[154] Additionally, e-readers allow readers to look up words or find more information about the topic immediately using an online dictionary.[155][156][157] Amazon reports that 85% of its e-book readers look up a word while reading.[158]

Printed books use three times more raw materials and 78 times more water to produce when compared to e-books.[159] While an e-reader costs more than most individual books, e-books may have a lower cost than paper books.[160] E-books may be printed for less than the price of traditional books using on-demand book printers.[161] Moreover, numerous e-books are available online free of charge on sites such as Project Gutenberg.[162] For example, all books printed before 1923 are in the public domain in the United States, which enables websites to host ebook versions of such titles for free.[163]

Depending on possible digital rights management, e-books (unlike physical books) can be backed up and recovered in the case of loss or damage to the device on which they are stored, a new copy can be downloaded without incurring an additional cost from the distributor, as well as being able to synchronize the reading location, highlights and bookmarks across several devices.[164]

Downsides

.jpg)

There may be a lack of privacy for the user's e-book reading activities; for example, Amazon knows the user's identity, what the user is reading, whether the user has finished the book, what page the user is on, how long the user has spent on each page, and which passages the user may have highlighted.[165] One obstacle to wide adoption of the e-book is that a large portion of people value the printed book as an object itself, including aspects such as the texture, smell, weight and appearance on the shelf.[166] Print books are also considered valuable cultural items, and symbols of liberal education and the humanities.[167] Kobo found that 60% of e-books that are purchased from their e-book store are never opened and found that the more expensive the book is, the more likely the reader would at least open the e-book.[168]

Joe Queenan has written about the pros and cons of e-books:

Electronic books are ideal for people who value the information contained in them, or who have vision problems, or who like to read on the subway, or who do not want other people to see how they are amusing themselves, or who have storage and clutter issues, but they are useless for people who are engaged in an intense, lifelong love affair with books. Books that we can touch; books that we can smell; books that we can depend on.[169]

While a paper book is vulnerable to various threats, including water damage, mold and theft, e-books files may be corrupted, deleted or otherwise lost as well as pirated. Where the ownership of a paper book is fairly straightforward (albeit subject to restrictions on renting or copying pages, depending on the book), the purchaser of an e-book's digital file has conditional access with the possible loss of access to the e-book due to digital rights management provisions, copyright issues, the provider's business failing or possibly if user's credit card expired.[170]

Market share

United States

In 2015, the Author Earnings Report estimated that Amazon held a 74% market share of the e-books sold in the U.S.[172] By the end of 2016, that year's Report estimated that Amazon held 80% of the e-book market share in the U.S.[138]

Canada

Spain

In 2013, Carrenho estimates that e-books would have a 15% market share in Spain in 2015.[174]

UK

According to Nielsen Book Research, e-book share went from 20% to 33% between 2012 and 2014, but down to 29% in the first quarter of 2015. Amazon-published and self-published titles accounted for 17 million of those books - worth £58m – in 2014, representing 5% of the overall book market and 15% of the digital market. The volume and value sales are similar to 2013 but up 70% since 2012.[175]

Germany

The Wischenbart Report 2015 estimates the e-book market share to be 4.3%.[176]

Brazil

The Brazilian e-book market is only emerging. Brazilians are technology savvy, and that attitude is shared by the government.[176] In 2013, around 2.5% of all trade titles sold were in digital format. This was a 400% growth over 2012 when only 0.5% of trade titles were digital. In 2014, the growth was slower, Brazil had 3.5% of its trade titles being sold as e-books.[176]

China

The Wischenbart Report 2015 estimates the e-book market share to be around 1%.[176]

Public domain books

Public domain books are those whose copyrights have expired, meaning they can be copied, edited, and sold freely without restrictions.[177] Many of them can be downloaded for free from websites like the Internet Archive in formats many E-readers support, like PDF, TXT, and EPUB. Books in other formats may be converted to an e-reader compatible format using for instance Calibre.

See also

References

- ↑ Gardiner, Eileen and Ronald G. Musto. "The Electronic Book." In Suarez, Michael Felix, and H. R. Woudhuysen. The Oxford Companion to the Book. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 164.

- ↑ "e-book Archived 2011-02-08 at the Wayback Machine.". Oxford Dictionaries. April 2010. Oxford Dictionaries. April 2010. Oxford University Press. (accessed September 2, 2010).

- ↑ "BBC - WebWise - What is an e-book?". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-02-04. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- 1 2 eBook Revenues Top Hardcover - GalleyCat Archived 2013-07-01 at the Wayback Machine.. Mediabistro.com (2012-06-15). Retrieved on 2013-08-28.

- ↑ Bhardwaj, Deepika (2015). "Do e-books really threaten the future of print?". newspaper. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- 1 2 "e-book Definition from PC Magazine Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2017-08-07.

- ↑ E-reading rises as device ownership jumps Archived 2014-03-27 at the Wayback Machine.. Pew Research. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ Brown, Bob, The Readies, Google Books, archived from the original on 2016-11-29, retrieved 2013-08-28 .

- 1 2 3 4 Schuessler, Jennifer (2010-04-11). "The Godfather of the E-Reader". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-06-25.

- ↑ García, Guillermo (25 January 2013). "Doña Angelita, la inventora gallega del libro electrónico". SINC (in Spanish). Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ↑ Lallanilla, Marc. "Is This 1949 Device the World's First E-Reader?". Live Science. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ↑ "Stop the reader, Fr. Busa has died". L'Osservatore Romano. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- 1 2 Priego, Ernesto (12 August 2011). "Father Roberto Busa: one academic's impact on HE and my career". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ↑ "Index Thomisticus", Corpus Thomisticum .

- 1 2 DeRose, Steven J; van Dam, Andries (1999). "Document Structure and Markup in the FRESS Hypertext System". Markup Languages. 1 (1): 7–32. doi:10.1162/109966299751940814.

- 1 2 Carmody, Steven; Gross, Walter; Nelson, Theodor H; Rice, David; van Dam, Andries (1969), "A Hypertext Editing System for the /360", in Faiman; Nievergelt, Pertinent Concepts in Computer Graphics: Proceedings of the Second 17 University of Illinois Conference on Computer Graphics, University of Illinois Press, pp. 291–330 .

- 1 2 van Dam, Andries; Rice, David E (1970), Computers and Publishing: Writing, Editing and Printing, Advances in Computers (10), Academic Press, pp. 145–74 .

- ↑ Reilly, Edwin D (Aug 30, 2003), Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology, Greenwood, p. 85, archived from the original on 2016-11-29 .

- ↑ Hamm, Steve (December 14, 1998), "Bits & Bytes: Making E-Books Easier on the Eyes", Business Week, p. 134B, archived from the original on May 2, 2012 .

- ↑ Yankelovich, Nicole; Meyrowitz, Norman; van Dam, Andries (October 1985), "Reading and Writing the Electronic Book", Computer, IEEE, 18 (10): 15–30, doi:10.1109/mc.1985.1662710 .

- ↑ Chisholm, Roderick M (16 August 2004). Person And Object: A Metaphysical Study. Psychology Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-0-415-29593-2. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ↑ "An experimental system for creating and presenting interactive graphical documents." ACM Transactions on Graphics 1(1), Jan. 1982

- ↑ Nicole Yankelovich; Norman K. Meyrowitz; Andries van Dam (1985). "Reading and Writing the Electronic Book". IEEE Computer Magazine. 18 (10): 15–30. doi:10.2200/S00215ED1V01Y200907ICR009.

- ↑ Michael S. Hart, Project Gutenberg, archived from the original on 2012-11-06

- ↑ Flood, Alison (8 September 2011). "Michael Hart, inventor of the ebook, dies aged 64". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ↑ Grimes, William (8 September 2011). "Michael Hart, a Pioneer of E-Books, Dies at 64". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 Alison Flood (2011-09-08). "Michael Hart, inventor of the ebook, dies aged 64". London: Guardian. Archived from the original on 2015-02-13. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ Personal Dynamic Media Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. – By Alan Kay and Adele Goldberg

- ↑ Wisher, Robert A.; Kincaid, J. Peter (March 1989). "Personal Electronic Aid for Maintenance: Final Summary Report" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center.

- ↑ EP0163511 A1

- ↑ The book and beyond: electronic publishing and the art of the book. Archived 2012-01-20 at the Wayback Machine. Text of an exhibition held at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1995.

- ↑ eBooks: 1993 – PDF, from past to present Archived 2016-04-25 at the Wayback Machine. Gutenberg News

- ↑ Where do these books come from? Archived 2014-12-24 at the Wayback Machine. Google Support. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ eBooks: la guerra digital global por el dominio del libro Archived 2011-05-12 at the Wayback Machine. – By Chimo Soler.

- ↑ "Frequently asked questions regarding e-books and U.S. libraries". Transforming Libraries. American Library Association. 2014-10-03. Archived from the original on 2014-10-16. Retrieved 2014-10-09.

- ↑ Doris Small. "E-books in libraries: some early experiences and reactions." Archived 2011-05-12 at the Wayback Machine. Searcher 8.9 (2000): 63–5.

- ↑ Genco, Barbara. "It's been Geometric! Archived 2010-10-06 at the Wayback Machine. Documenting the Growth and Acceptance of eBooks in America's Urban Public Libraries." IFLA Conference, July 2009.

- ↑ Saylor, Michael (2012). The Mobile Wave: How Mobile Intelligence Will Change Everything. Vanguard Press. p. 124. ISBN 1-59315-720-7.

- ↑ Libraries Connect Communities: Public Library Funding & Technology Access Study 2009–2010. ala.org

- ↑ "66% of Public Libraries in US offering e-Books". Libraries.wright.edu. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ "At the Tipping Point: Four voices probe the top e-book issues for librarians." Library Journal, August 2010

- ↑ "J.K. Rowling refuses e-books for Potter". USA Today. 2005-06-14. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14.

- ↑ Frederiksen, Linda; Cummings, Joel; Cummings, Lara; Carroll, Diane (2011). "Ebooks and Interlibrary Loan: Licensed to Fill?". Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery & Electronic Reserve. 21: 117–131. doi:10.1080/1072303X.2011.585102.

- 1 2 3 Becker, B. W. (2011). "The e-Book Apocalypse: A Survivor's Guide". Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian. 30 (3): 181–4. doi:10.1080/01639269.2011.591278.

- ↑ Affection for PDA Archived 2012-06-23 at the Wayback Machine. Inside Higher Ed Steve Kolowich, June 20, 2012

- 1 2 "Library Ebook Vendors Assess the Road Ahead". The Digital Shift. Archived from the original on 2014-08-11.

- ↑ John Hilton III; David Wiley (Winter 2010). "The Short-Term Influence of Free Digital Versions of Books on Print Sales". Journal of Electronic Publishing. doi:10.3998/3336451.0013.101.

- ↑ Falcone, John (July 6, 2010). "Kindle vs. Nook vs. iPad: Which e-book reader should you buy?". CNet. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- 1 2 "E-Books Top Hardcovers at Amazon". The New York Times. 2010-07-19. Archived from the original on 2011-09-06. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ↑ "Amazon Media Room: Press Releases". Phx.corporate-ir.net. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ Lynn Neary; Don Gonyea (2010-07-27). "Conflict Widens In E-Books Publishing". NPR. Archived from the original on 2010-07-27. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ↑ Matt Phillips (2009-05-07). "Kindle DX: Must You Turn it Off for Takeoff and Landing?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2011-08-30. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- ↑ "Cleared for take-off: Europe allows use of e-readers on planes from gate to gate". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25.

- ↑ In Europe, Slower Growth for e-Books Archived 2015-10-26 at the Wayback Machine.. New York Times (2014-11-12). Retrieved on 2014-12-05.

- ↑ Neil Gaiman (1988). DON'T PANIC: The official Hitch-Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy companion. Titan Books. ISBN 1-85286-013-8. OCLC 24722438.

- ↑ "Pioneering the computational linguistics and the largest published work of all time". IBM. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-08-11.

- ↑ Miller, Michael W. (1989). "A Brave New World: Streams of 1s and 0s". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Religion: High-Tech Bible Archived 2016-05-30 at the Wayback Machine. Time

- ↑ Gutermann, Jimmy, 'Hypertext Before the Web,' Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1999

- ↑ Cohen, Michael (2013-12-19). "Scotched: Fair thoughts and happy hours did not attend upon an early enhanced-book adaptation of Macbeth". The Magazine. Seattle, WA: Aperiodical LLC (32). Archived from the original on 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- ↑ "Foto Franco, l'uomo che inventò l'e-book "Ma nel 1993 nessuno ci diede retta" – 1 di 10". Milano.repubblica.it. Archived from the original on 2011-09-01. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ Incipit 1992

- ↑ Coburn, M.; Burrows, P.; Loi, D.; Wilkins, L. (2001). Cope, B. & Kalantzis, D. Melbourne, eds. "E-book readers directions in enabling technologies". Print and Electronic Text Convergence. Common Ground. pp. 145–182.

- ↑ "All Eight Roy Grace Novels by Peter James Now Available in e-Book Format in the United States". Prweb.com. 31 January 2013. Archived from the original on 19 May 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ↑ Publication: Hugo and Nebula Anthology 1993 Archived 2016-08-21 at the Wayback Machine. The Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- ↑ Ebook timeline Archived 2016-09-21 at the Wayback Machine. 3 January 2002.

- ↑ Alexis KIRKE (1995). "The Emuse: Symbiosis and the Principles of Hyperpoetry". Brink. Electronic Poetry Centre, University of Buffalo. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- ↑ Day, B. H.; Wortman, W. A. (2000). Literature in English: A Guide for Librarians in the Digital Age. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries. p. 170. ISBN 0-8389-8081-3.

- ↑ The Future of Books Archived 2016-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Wired, February 2006

- ↑ Journal, Alec Klein Staff Reporter of The Wall Street. "A New Printing Technology Sets Off a High-Stakes Race". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ↑ eBooks: 1998 – The first ebook readers Archived 2015-02-06 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ↑ Hamilton, Joan (1999), "Downloaded Any Good Books Lately?", BusinessWeek, archived from the original on 2016-03-04

- ↑ Judge, Paul (1998-11-16), "E-Books: A Library On Your Lap", BusinessWeek, archived from the original on February 8, 2000

- ↑ "Prime Palaver #6". Baen.com. 2002-04-15. Archived from the original on 2010-01-02. Retrieved 2010-01-28.

- ↑ Tuscaloosa News June 29, 2000

- ↑ Spotlight | National Inventors Hall of Fame Archived 2015-12-05 at the Wayback Machine. 2016

- ↑ De Abrew, Karl (April 24, 2000). "eBooks are Here to Stay". Adobe.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2010. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ Corín Tellado

- ↑ "Microsoft Reader Archived 2005-08-22 at the Wayback Machine. August 2000

- ↑ Pearson, David (2006). Bowman, J, ed. British Librarianship and Information Work 1991-2000: Rare book librarianship and historical bibliography. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-7546-4779-9.

- ↑ Palm Digital Media and OverDrive, Inc. Announce Plans for Global Distribution of Palm Reader eBooks for Handheld Devices Archived 2016-04-27 at the Wayback Machine. April 30, 2002

- ↑ "Sony LIBRIe – The first ever E-ink e-book Reader". Mobile mag. 2004-03-25. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ↑ "Checks Out Library Books – News from". Google. 2004-12-14. Archived from the original on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ "Franklin sells interest in company, retires shares". Philadelphia Business Journal. 2005-03-31. Archived from the original on 2010-08-29. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ Samuelson, Pamela (July 2010). "Legally speaking: Should the Google Book settlement be approved?". Communications of the ACM. 53 (7): 32–34. doi:10.1145/1785414.1785429.

- ↑ "Update your PRS-500 Reader", Style, Sony, archived from the original on January 7, 2010, retrieved November 18, 2009 .

- ↑ "OPS 2.0 Elevated to Official IDPF Standard". IDPF. eBooklyn. Oct 15, 2007. Archived from the original on 2014-10-28.

- 1 2 Patel, Nilay (November 21, 2007). "Kindle Sells Out in 5.5 Hours". Engadget.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Cybook specifications". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Slattery, Brennon (November 10, 2009). "Kindle for PC Released, Color Kindle Coming Soon?". PC World. Archived from the original on October 28, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ↑ Kehe, Marjorie (January 6, 2010). "Kindle DX: Amazon takes on the world". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Bookeen debuts Orizon touchscreen e-reader". Engadget. Archived from the original on 2011-11-07. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ "Apple Launches iPad 2 (Announcement)" (Press release). Apple. March 2, 2011. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- ↑ Andrew Albanese (6 December 2010). "Google Launches Google eBooks, Formerly Google Editions". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017.

- ↑ Obaiduzzaman Khan (August 22, 2010). "Pocketbook e-reader with Android". thetechjournal.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Scarcity of Giller-winning 'Sentimentalists' a boon to eBook sales" Archived 2012-11-20 at the Wayback Machine.. Toronto Star, November 12, 2010.

- ↑ Rapaport, Lisa (2011-05-19). "Amazon.com Says Kindle E-Book Sales Surpass Printed Books for First Time". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2011-11-05. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ "The Simple Touch Reader". LJ Interactive 24th May 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-08-07.

- ↑ "Bookeen launches a new e-book store". E-reader-info.com. 2011-08-01. Archived from the original on 2011-10-12. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- 1 2 Hughes, Evan. (2013-08-20) The Publishing Industry is Thriving Archived 2017-02-17 at the Wayback Machine.. New Republic. Retrieved on 2013-10-09.

- ↑ "Kbuuk announces competition for self-published authors". Prnewswire.com. June 15, 2012. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ Chloe Albanesius (January 19, 2012). "Apple Targets Educators Via iBooks 2, iBooks Author, iTunes U App". PCMag.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017.

- ↑ Josh Lowensohn (January 19, 2012). "Apple unveils iBooks 2 for digital textbooks, self-pub app (live blog)". CNET. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Gigapedia: The greatest, largest and the best website for downloading eBooks". Archived from the original on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ↑ Skoobe: publishing houses start e-book library Archived 2013-03-18 at the Wayback Machine. (German)

- ↑ Cooper, Charles. (2012-03-09) Go feds! E-books are way overpriced | Internet & Media – CNET News Archived 2012-03-15 at the Wayback Machine.. News.cnet.com. Retrieved on 2012-04-12.

- ↑ Catan, Thomas; Trachtenberg, Jeffrey A. (March 9, 2012). "U.S. Warns Apple, Publishers". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ↑ "IT Magazine about ereaders". Pocketbook-int.com. 2012-04-25. Archived from the original on 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ↑ "Test of ereaders in 2012". Pocketbook-int.com. 2012-06-20. Archived from the original on 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- 1 2 Phil Wahba Reuters (June 25, 2013). "Barnes & Noble to stop making most of its own Nook tablets". NBC News. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013.

- ↑ Eric Slivka (June 12, 2013). "Apple Claims 20% of U.S. E-Book Market, Double Previous Estimates". MacRumors. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013.

- ↑ Carnoy, David (2013-04-15). "Kobo Unveils Aura HD: Porsche of eReaders". CNET. CBS Media. Archived from the original on 2014-05-25. Retrieved 2014-05-24.

- ↑ Boesen, Steffen (2015-05-12). "Ung millionær vil skabe litterær spotify". Politiken. Archived from the original on 2014-08-04. Retrieved 2015-05-12.

- ↑ Judge finds Apple guilty of fixing e-book prices (Updated) Archived 2015-01-14 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Chaey, Christina (2013-09-05). "With Oyster, keep 100,000 books in your pocket for $10 a month". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 2013-11-24. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ↑ "Google Books ruled legal in massive win for fair use". Archived from the original on 2017-04-30.

- ↑ "Siding With Google, Judge Says Book Search Does Not Infringe Copyright" Archived 2017-01-20 at the Wayback Machine., Claire Cain Miller and Julie Bosman, The New York Times, November 14, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- ↑ Metz, Cade. "Scribd Challenges Amazon and Apple With 'Netflix for Books'". Wired. Archived from the original on 2013-12-30. Retrieved 2013-12-30.

- ↑ About Kindle Unlimited, Amazon, archived from the original on 2017-08-06 .

- ↑ "Kobo crams 1.5 million pixels into its 6.8" Aura H2O e-reader". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2014-06-14. Retrieved 2014-04-16.

- ↑ "Apple faces certified class action suit over e-book price conspiracy". Ars. Archived from the original on 2014-06-20. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ "Apple settles ebook antitrust case, set to pay millions in damages". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 2014-06-17. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ Apple Loses Appeal in eBook Antitrust Case, archived from the original on 1 July 2015, retrieved 30 June 2015 .

- ↑ New Bookerly Font and Typography Features, Amazon, archived from the original on 2016-04-14 .

- ↑ / Oyster HQ Blog Archived 2015-09-30 at the Wayback Machine.. September 22, 2015

- ↑ migration (2015-09-30). "Pinjam e-buku di KLIA, Berita Dunia - BeritaHarian.sg". BeritaHarian. Archived from the original on 2016-05-09. Retrieved 2016-04-27.

- ↑ Amazon Kindle Voyage review: Amazon's best e-reader yet, CNet, archived from the original on 2015-02-15, retrieved Feb 24, 2015 .

- ↑ Nook Glowlight Plus Now Available – Waterproof, Dust-Proof, 300ppi Screen, and only $129 Archived 2015-10-21 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ "Google book-scanning project legal, says U.S. appeals court". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2015-10-22.

- ↑ Playster audiobook and e-book subscription debuts in the US Archived 2016-01-03 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ Apple is On the Hook for the $450m Settlement after Supreme Court Rejects Apple's eBook Conspiracy Appeal Archived 2016-03-08 at the Wayback Machine. March 7, 2016

- ↑ US Supreme Court Rejects Challenge to Google Book-Scanning Project Archived 2016-04-18 at the Wayback Machine. April 18, 2016

- ↑ Amazon's Kindle Oasis is the funkiest e-reader it's ever made Archived 2017-08-08 at the Wayback Machine. The Verge Retrieved April 13, 2016

- ↑ Kobo Aura One Leaks, Has a 300 PPI 7.8″ E-ink Screen for 229 Euros Archived 2016-08-12 at the Wayback Machine. The Digital Reader, Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- ↑ How Perlego is making e-books cheaper for university students Archived 2017-02-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Wood, Zoe (17 March 2017). "Paperback fighter: sales of physical books now outperform digital titles". Archived from the original on 22 March 2017 – via The Guardian.

- ↑ E-Book Sales Down 17% In First Three Quarters Of 2016 Archived 2017-03-07 at the Wayback Machine. Forbes, Retrieved 6 March 2017

- 1 2 3 Hiltzik, Michael (1 May 2017). "No, ebooks aren't dying — but their quest to dominate the reading world has hit a speed bump". LA Times. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ↑ McCracken, Jeffrey (2011-03-23). "Barnes & Noble Said to Be Likely to End Search Without Buyer". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2011-11-05. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- 1 2 Suleman, Khidr (September 20, 2010). "Sony Reader Touch and Amazon Kindle 3 go head-to-head". The Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Beyond Ebooks". Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ↑ Patel, Nilay (January 27, 2010). "The Apple iPad: starting at $499". Engadget. Archived from the original on January 29, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ↑ Covert, Adrian. "Kobo Touch E-Reader: You'll Want to Love It, But ..." Gizmodo.com. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ↑ "Kobo eReader Touch Specs". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ↑ Kozlowski, Michael. "Hands on review of the Pocketbook PRO 902 9.7 inch e-Reader". goodereader.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ↑ "PocketBook Touch Specs". Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- ↑ Pogue, David (2009-07-17). "Case where Amazon remotely deleted titles from purchasers' devices". Pogue.blogs.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-09. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ "Tor/Forge Plans DRM-Free e-Books By July". Publishers Weekly. 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Kimberly Maul Checking Out the Machines Behind Book Digitization. The ebook standard. February 21, 2006

- ↑ "Best Sellers. E-BOOK FICTION". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ "Best Sellers. E-BOOK NONFICTION". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ The Futility of E-Book Completion Data for Trade Publishers Ala Serafin 14 March 14, 2015

- ↑ Ebooks can tell which novels you didn't finish Archived 2016-10-12 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Harris, Christopher (2009). "The Truth About Ebooks". School Library Journal. 55 (6): 18.

- ↑ Taipale, S (2014). "The Affordances of Reading/Writing on Paper and Digitally in Finland". Telematics and Informatics. 32 (4): 532–542. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2013.11.003.

- ↑ Fortunati, L.; Vincent, J. (2014). "Sociological Insights into writing/reading on paper and writing/reading digitally". Telematics and Informatics. 31 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2013.02.005.

- ↑ Yates, Emma; Books, Guardian Unlimited (2001-12-19). "Ebooks: a beginner's guide". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ↑ What are the most looked up words on the Kindle? Archived 2015-10-19 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ↑ Goleman, Daniel (2010-04-04). "How Green Is My iPad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ Greenfield, Jeremy (January 9, 2013). "Tracking the Price of Ebooks: Average Price of Ebook Best-Sellers in a Two-Month Tailspin". Digital Book World. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ Finder, Alan (August 15, 2012). "The Joys and Hazards of Self-Publishing on the Web". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

Digital publishing and print on demand have significantly reduced the cost of producing a book.

- ↑ "Project Gutenberg". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States Archived 2015-02-26 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ↑ "Sync Across Kindle Devices & Apps". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ The Fifty Shades of Grey Paradox Archived 2015-03-15 at the Wayback Machine.. Slate. Feb 13, 2015.

- ↑ Catone, Josh (January 16, 2013). "Why Printed Books Will Never Die". Mashable. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ Ballatore, Andrea; Natale, Simone (2015-05-18). "E-readers and the death of the book: Or, new media and the myth of the disappearing medium". New Media & Society: 1461444815586984. doi:10.1177/1461444815586984. ISSN 1461-4448. Archived from the original on 2016-03-15.

- ↑ People are Not Reading the e-Books they Buy Anymore Archived 2015-10-22 at the Wayback Machine. September 20, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ↑ Queenan, Joe (2012). One for the Books. Viking Adult. ISBN 9780670025824.

- ↑ Michael Hiltzi (October 16, 2016). "Consumer deception? That 'Buy Now' button on Amazon or iTunes may not mean you own what you paid for". LATimes.com. LA Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ↑ "Adding up the invisible ebook market – analysis of Author Earnings January 2015". Publishing Technology. February 9, 2015. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ Amazon Has an Even Bigger Share of the eBook Market Than We Thought – Author Earnings Report Archived 2015-10-14 at the Wayback Machine. 9 October 2015.

- ↑ Barbour, Mary Beth (2012-04-19). "Latest Wave of Ipsos Study Reveals Mobile Device Brands Canadian Consumers are Considering in 2012". Ipsos Reid. Archived from the original on 2012-05-23. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ↑ Rüdiger, W.; Carrenho, C. (2013). Global eBook: Current Conditions & Future Projections. London. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ Campbell, Lisa (June 8, 2015). "E-book market share down slightly in 2015". Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Wischenbart, Rüdiger (2015). Global E-book Report 2015.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Boyle, James (2008). The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind. CSPD. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-300-13740-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Electronic books. |

- James, Bradley (November 20, 2002). The Electronic Book: Looking Beyond the Physical Codex, SciNet

- Cory Doctorow (February 12, 2004). Ebooks: Neither E, Nor Books, O'Reilly Emerging Technologies Conference

- Lynch, Clifford (May 28, 2001). The Battle to Define the Future of the Book in the Digital World, First Monday – Peer reviewed journal.

- "Scanning the horizon of books & libraries - Google book settlement and online book rights", Truth dig, Sep 29, 2009

- "E-Books Spark Battle Inside Publishing Industry", The Washington Post, 27 Dec 2009 .

- Dene Grigar & Stuart Moulthrop (2013-2016) "Pathfinders: Documenting the Experience of Early Digital Literature", Washington State University Vancouver, July 1, 2013.

- E-book at Curlie (based on DMOZ)