Eads Bridge

| Eads Bridge | |

|---|---|

The Eads Bridge from St. Louis, to East St. Louis, Illinois, over the Mississippi River | |

| Coordinates | 38°37′41″N 90°10′17″W / 38.62806°N 90.17139°W |

| Carries |

4 highway lanes 2 MetroLink tracks |

| Crosses | Mississippi River |

| Locale | St. Louis, Missouri and East St. Louis, Illinois |

| Other name(s) | World's First All Steel Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Arch bridge |

| Total length | 6,442 ft (1,964 m) |

| Width | 46 ft (14 m) |

| Longest span | 520 ft (158 m) |

| Clearance below | 88 ft (27 m) |

| History | |

| Designer | James B. Eads |

| Construction start | 1867[1] |

| Opened | 1874[1] |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic |

8,100 (2014)[2] |

|

Eads Bridge | |

| |

| Location | St. Louis, Missouri |

| Coordinates | 38°37′41″N 90°10′17″W / 38.62806°N 90.17139°WCoordinates: 38°37′41″N 90°10′17″W / 38.62806°N 90.17139°W |

| Built | 1867-1874 |

| Architect | Eads, Capt. James B. |

| Architectural style | Other |

| NRHP reference # | 66000946[3] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | January 29, 1964[4] |

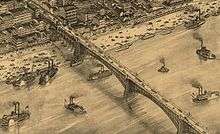

The Eads Bridge is a steel combined road and railway bridge over the Mississippi River connecting the cities of St. Louis, Missouri and East St. Louis, Illinois. It was envisioned and financed by a young Andrew Carnegie. It was considered critical to industry and trade in both cities, and especially stimulated industrial development east of the river. Opened in 1874, it was one of the earliest long bridges built across the Mississippi, the world's first all-steel construction,[5] and built high enough so steamboats could travel underneath. The St. Louis Landmark is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a National Historic Landmark. As of April 2014, it carries about 8,100 vehicles daily, down 3,000 since the new Stan Musial Veterans Memorial Bridge opened in February 2014.[2]

The bridge is named for its designer and builder, James B. Eads. When completed in 1874, the Eads Bridge was the longest arch bridge in the world, with an overall length of 6,442 feet (1,964 m). The ribbed steel arch spans were considered daring, as was the use of steel as a primary structural material. This was the first such use of true steel in a major bridge.[6] The cost of building the bridge was nearly $10 million ($220 million with inflation[7] ).[8]

The Eads Bridge was the first bridge to be built using exclusively cantilever support methods, and one of the first to make use of pneumatic caissons. Numerous workers who operated in the Eads Bridge caissons, still among the deepest ever sunk, suffered from "caisson disease" (also known as "the bends" or decompression sickness).[9] Fifteen workers died, two other workers were permanently disabled, and 77 were severely afflicted.[9][10]

On June 14, 1874, John Robinson led a "test elephant" on a stroll across the new Eads Bridge to prove that it was safe.[11] A big crowd cheered as the elephant from a traveling circus lumbered toward Illinois. Popular belief held that elephants had instincts that would make them avoid setting foot on unsafe structures. Two weeks later, Eads sent 14 locomotives back and forth across the bridge at one time.[12] The opening day celebration on July 4, 1874, featured a parade that stretched for 15 miles (24 km) through the streets of St. Louis.[13]

The Eads Bridge became an iconic image of the city of St. Louis, from the time of its erection until 1965 when the Gateway Arch was constructed. It is still in use. The bridge crosses the St. Louis riverfront between Laclede's Landing, to the north, and the grounds of the Gateway Arch, to the south. Today the road deck has been restored, allowing vehicular and pedestrian traffic to cross the river. The St. Louis MetroLink light rail system has used the rail deck since 1993.

History

The Eads Bridge was built by the Illinois and St. Louis Bridge Company, with the Keystone Bridge Company serving as subcontractor for superstructure erection.[14]

Because of the increased reach of newly constructed railroads, river shipping trade had declined in importance compared to the antebellum years. Chicago was fast gaining as the center of commerce in the West. The bridge was conceived as a solution for St. Louis to regain eminence by connecting railroad and vehicle transportation across the river. Although he had no prior experience in bridge building, James Eads was chosen as chief engineer for the bridge.[15]

In an attempt to secure their future, steamboat interests successfully lobbied to place restrictions on bridge construction, requiring spans and heights previously unheard of. This was ostensibly to maintain sufficient operating room for steamboats beneath the bridge's base for the then foreseeable future. The unproclaimed purpose was to require a bridge so grand and lofty that it was impossible to erect according to conventional building techniques. The steamboat parties planned to prevent any structure from being built, in order to ensure continued dependence on river traffic to sustain commerce in the region.

Such a bridge required a radical design solution. The Mississippi River's strong current was almost 12 1⁄2 feet per second (3.8 m/s) and the builders had to battle ice floes in the winter.[15] The ribbed arch had been a known construction technique for centuries. The triple span, tubular metallic arch construction was supported by two shore abutments and two mid-river piers. Four pairs of arches per span (upper and lower) were set eight feet (2.4 m) apart, supporting an upper deck for vehicular traffic and a lower deck for rail traffic.

Construction involved varied and confusing design elements and pressures. State and federal charters precluded suspension or draw bridges, or wood construction. There were constraints on span size and the height above the water line. The location required reconciling differences in heights - from the low Illinois floodplain of the east bank of the river to the high Missouri cliff on the west bank. The bedrock could only be reached by deep drilling, as it was 38 m below water level on the Illinois side and 26 m below on the Missouri side.[16][17]

These pressures resulted in a bridge noted as innovative for precision and accuracy of construction and quality control. This was the first use of structural alloy steel in a major building construction, through use of cast chromium steel components. The completed bridge also relied on significant—and unknown—amounts of wrought iron.[6] Eads argued that the great compressive strength of steel was ideal for use in the upright arch design. His decision resulted from a curious combination of chance and necessity, due to the insufficient strength of alternative material choices.

The particular physical difficulties of the site stimulated interesting solutions to construction problems. The deep caissons used for pier and abutment construction signaled a new chapter in civil engineering. Piers were sunk almost 100 feet (30 m) below the river's surface.[15] Unable to construct falsework to erect the arches, because they would obstruct river traffic, Eads's engineers devised a cantilevered rigging system to close the arches.

Masonry piers were built to heights of almost 120 feet (37 m), about the height of a ten-story building. About 78 feet (24 m) of that span was driven through the sandy riverbed until it hit bedrock. Eads implemented a building method that he had observed in Europe, whereby masonry was set atop a metal chamber filled with compressed air. Stone was added to the chamber, which caused the caisson to sink. Workers dove into the caisson to shovel sand into a pump that shot it out into the air so the masonry could be sunk into the riverbed. Suffering from what is now known as the bends, thirteen men died during this process and two were paralyzed; others were quite ill. The Eads Bridge was built on the deepest pneumatic caisson ever constructed.[15]

Eads Bridge was recognized as an innovative and exciting achievement. Eads secured 47 patents during his lifetime, many of which were taken out for parts of the bridge's structure and devices for its construction.[15] President Ulysses S. Grant dedicated the bridge on July 4, 1874, and General William T. Sherman drove the gold spike completing construction. After completion, 14 locomotives crossed the bridge to prove its stability.[15]

The Eads Bridge was undercapitalized during construction and burdened with debt. Because of its historic focus on the Mississippi and river trade, St. Louis lacked adequate rail terminal facilities, and the bridge was poorly planned to coordinate rail access. Although an engineering and aesthetic success, the bridge operations became bankrupt within a year of opening. The railroads boycotted the bridge, resulting in a loss of tolls. The bridge was later sold at auction for 20 cents on the dollar. This sale caused the National Bank of the State of Missouri to fold, which was the largest bank failure in the United States at that time. Eads did not suffer financial consequences. Many involved with financing the bridge were indicted, but Eads was not.[15]

Granite for the bridge came from the Iron County, Missouri, quarry of B. Gratz Brown, Missouri Governor and U.S. Senator, who had helped secure federal financing for the bridge.[18]

In 1949, the bridge's strength was tested with electromagnetic strain gauges. It was determined that Eads' original estimation of an allowable load of 3,000 pounds per foot (4,500 kg/m) could be raised to 5,000 pounds per foot (7,400 kg/m). The Eads Bridge is still considered one of the greatest bridges ever built.[15]

The Merchants Exchange eventually lost ownership of the bridge to the Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis. The Exchange, fearing a Terminal Railroad rail monopoly on the bridges, built the Merchants Bridge. It was also acquired by the Terminal Railroad. In 1989 the Terminal Railroad transferred the bridge to the City of St. Louis in exchange for the MacArthur Bridge.[19]

Eads Bridge had long hosted only passenger trains on its rail deck. In the late 20th century, however, passenger traffic had declined because of individual automobile use, and the railroad industry was restructuring. By the 1970s, the Terminal Railroad Association had abandoned its Eads trackage. The bridge had lost all remaining passenger rail traffic to the MacArthur Bridge during the early years of Amtrak; the dimensions of modern passenger diesels were incompatible with both the bridge and the adjoining tunnel linking the Union Station trackage with Eads.

In 1998, the Naval Facilities Engineering Service Center investigated the effects of the ramming of the bridge by the barge Anne Holly on April 4 of that year. The ramming resulted in the near breakaway of the SS Admiral, a riverboat casino. Implementing several recommended changes reduced the odds of this happening in the future.[20]

Recognition

In 1898 the bridge was featured on the $2 Trans-Mississippi Issue of postage stamps. One hundred years later the design was reprinted in a commemorative souvenir sheet.

The bridge was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1964, in recognition of its innovations in design, materials, construction methods, and importance in the history of large-scale engineering projects.[21]

During the bridge's construction, The New York Times called it The World's Eighth Wonder.[22] On its 100th anniversary, the Times' architectural critic, Ada Louise Huxtable, described it as "among the most beautiful works of man."[15]

See also

- Chain of Rocks Bridge

- Martin Luther King Bridge

- McKinley Bridge

- Merchants Bridge

- Poplar Street Bridge

- List of crossings of the Upper Mississippi River

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Missouri

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Illinois

- National Register of Historic Places listings in St. Clair County, Illinois

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Downtown and Downtown West St. Louis

- List of bridges on the National Register of Historic Places in Illinois

- List of bridges on the National Register of Historic Places in Missouri

References

- 1 2 Eads Bridge at Structurae

- 1 2 "IDOT: New bridge carrying less traffic than originally expected". Belleville News Democrat. April 14, 2014. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- ↑ National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Eads Bridge". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ↑ Jackson, Donald C. (1996). Great American Bridges and Dams. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-14385-5.

- 1 2 DeLony, Eric. "Context for World Heritage Bridges". International Council on Monuments and Sites. Archived from the original on February 21, 2005. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ↑ St. Louis Up To Date: The Great Industrial Hive of the Mississippi Valley. Richly Endowed by Nature as a Port of Entry, a Manufacturing Centre, and a Place of Residence. A Glance at Her History, a Review of Her Commerce, and a Description of Her Leading Business Enterprises; With Illustrations of Her Public and Commercial Buildings and Places of Interest. St. Louis: Consolidated Illustrating Company. 1895.

- 1 2 Butler, WP (Winter 2004). "Caisson Disease During the Construction of the Eads and Brooklyn Bridges: A Review". Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine. 31 (4): 445–59. PMID 15686275. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ↑ "James B. Eads and His Amazing Bridge at St. Louis" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- ↑ "'Test Elephant' Proves Eads Bridge Is Safe". This Day In History. History Channel. June 14, 1874.

- ↑ "St. Louis People 365". Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ↑ Jackson, Robert W. (2001). Rails Across the Mississippi: A History of the St. Louis Bridge. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. p. 199.

- ↑ Woodward, C. M. (1881). A History of the St. Louis Bridge. St. Louis: G. I. Jones.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Shepley, Carol Ferring (2008). Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine Cemetery. St. Louis: Missouri History Museum.

- ↑ Condit, C.W. Technology and Culture. vol. 1. pp. 78–93.

- ↑ From material recorded by Kevin Murphy, Historian HAER, April 1984 in the public domain.

- ↑ "Past & Repast = The History and Hospitality of the Missouri Governor's Mansion", Missouri Mansion Preservation, Inc., 1983

- ↑ "TRRA History". Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2008.

- ↑ National Transportation Safety Board (September 8, 2000). Marine Accident Report: Ramming of the Eads Bridge by Barges in Tow on the M/V Anne Holly with Subsequent Ramming and Near Breakaway of the President Casino on the Admiral, St. Louis Harbor, Missouri, April 4, 1998. Washington, DC: National Transportation Safety Board – via docstock.com.

- ↑ "NHL Nomination for Eads Bridge". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ↑ "The St. Louis Bridge – Description of the Great Roadway Across the Father of Waters The World's Eighth Wonder". New York Times. May 17, 1873. p. 4. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

Further reading

- Cook, Richard J. (1987). The Beauty of Railroad Bridges in North America: Then and Now. San Marino, CA: Golden West Books. ISBN 0-87095-097-5.

- Kouwenhoven, John A. (1982). "The Designing of the Eads Bridge" (PDF). Technology and Culture. 23 (4): 535–568.

- Miller, Howard S. & Scott, Quinta (1979). The Eads Bridge. Columbia: University of Missouri Press.

- "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eads Bridge. |

- National Historic Landmark Designation - Statement of Significance

- Eads Bridge - the History and Heritage of Civil Engineering webpage (American Society of Civil Engineers)

- Eads Bridge at Structurae

- Bridge Pros: Eads Bridge

- Bridge info at Historic Bridges of the United States.

- maps.google.com zoomed in, hybrid mode

- High resolution panoramic image of an Eads Bridge span

- Picture, circa 1980

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. MO-1190, "Eads Bridge, Spanning Mississippi River at Washington Street, Saint Louis, Independent City, MO"

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. MO-12, "Eads Bridge, Spanning Mississippi River at Washington Street, Saint Louis, Independent City, MO"

- "Eads Bridge photographs". University of Missouri–St. Louis.

- Engineering Illustrated London : Office for Advertisements and Publication, July 14, 1871