Dungeness Nuclear Power Station

| Dungeness A Nuclear Power Station | |

|---|---|

Dungeness A | |

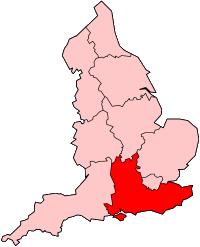

| Country | England |

| Location | Kent, South East England |

| Coordinates | 50°54′50″N 0°57′50″E / 50.913889°N 0.963889°ECoordinates: 50°54′50″N 0°57′50″E / 50.913889°N 0.963889°E |

| Status | Decommissioning, B |

| Commission date | 1965 |

| Decommission date | 2006 |

| Owner(s) | NDA |

| Operator(s) | Magnox Ltd |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactor type | Magnox |

| Reactor supplier | The Nuclear Power Group |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Nuclear |

| Power generation | |

| Units decommissioned | 2 X 219 MWe net |

| Nameplate capacity | 500 MWe |

|

Website www | |

| grid reference TR0832016959 | |

| Dungeness B Nuclear Power Station | |

|---|---|

|

Dungeness B | |

| Country | England |

| Location | Kent, South East England |

| Coordinates | 50°54′50″N 0°57′50″E / 50.913889°N 0.963889°E |

| Status | Operational, O |

| Construction began | 1965 |

| Commission date | 1983 |

| Decommission date | Expected 2028 |

| Operator(s) | EDF Energy |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactor type | Advanced gas cooled reactor |

| Reactor supplier | Fairey Engineering Ltd |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Nuclear |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | 2 x 600 MWe (Operating at ~545 MWe net[1] ) |

| Nameplate capacity | 1090 MWe |

|

Website www | |

| grid reference TR0832016959 | |

Dungeness nuclear power station may refer to either one or both of a pair of nuclear power stations, only one of which is still operational, located on the Dungeness headland in the south of Kent, England.

Dungeness A

Dungeness A is a legacy Magnox power station that was connected to the National Grid in 1965 and has reached the end of its life. It possessed two nuclear reactors producing 219 MW of electricity each, with a total capacity of 438 MW.[2] The construction was undertaken by a consortium known as the Nuclear Power Group ('TNPG').[3] The reactors were supplied by TNPG and the turbines by C. A. Parsons & Co.[2]

On 31 December 2006 the A station ceased power generation. Defuelling was completed in June 2012[4] and the demolition of the turbine hall was completed in June 2015.[5] It is expected to enter the 'care and maintenance' stage of decommissioning in 2027.[4]

Dungeness B

Dungeness B is an advanced gas-cooled reactor (AGR) power station consisting of two 615 MW reactors, which began operation in 1983 and 1985 respectively. Dungeness B was the first commercial scale AGR power station to be constructed. Its design was based on the much smaller Windscale AGR prototype, the WAGR. The £89 million contract was awarded in August 1965 to Atomic Power Construction ('APC'),[6] a consortium backed by Crompton Parkinson, Fairey Engineering, International Combustion and Richardsons Westgarth.[3] The completion date was set as 1970.

During construction, many problems were encountered in scaling up the WAGR design. Problems with the construction of the pressure vessel liner had distorted it, so that the boilers, which were to fit in an annular space between the reactor and the pressure vessel, could not be installed, and the liner had to be partially dismantled and rebuilt. This work only cost about £200,000, but there was a huge cost of financing an extra 18 unproductive months for a power station costing around £100 million, of which some 60% was already on the ground.[7] Serious problems were also discovered with the design of the boilers, which had to withstand the pounding of hot carbon dioxide (CO2), pressurised to 600 pounds per square inch (4,100 kPa) and pumped around the reactor coolant circuit by massive gas circulators. As a consequence, the casings, hangers and tube supports all had to be redesigned. The cost of the modifications, and financing during the delays, caused severe financial pressures for the consortium and its backers, and in 1969 APC collapsed into administration.

The CEGB took over project management, imposed light penalties in order not to cripple Fairey and International Combustion, and appointed British Nuclear Design and Construction (BNDC) as main contractor. In 1971, problems with corrosion of mild steel components in the first generation Magnox reactors gave the designers cause for concern. The Dungeness B restraint couplings - mechanical linkages that held the graphite core in place whilst allowing it to expand and contract in response to temperature changes - were made of mild steel and could be subject to the same corrosion. It was decided to replace them with components made from a new material.[8] In 1972, problems were found with the galvanised wire that was used to attach thermocouples to stainless steel boiler tubes. During heat treatment of the tubes at temperatures up to 1,050°C, the galvanising zinc diffused into the tubes and made them brittle. The cost had by then risen to £170 million.[9] By 1975, the CEGB was reporting that the power station would not be completed until 1977 and that its cost had risen to £280 million.[10] By 1979 the cost had risen further to £410 million.[11] Reactor 1 first generated power on 3 April 1983, some 13 years behind schedule and at a cost of £685 million, four times the initial estimate in inflation-adjusted terms.[12]

As with the "A" station, the turbines were built by C.A. Parsons & Company[2] and the station has two 600 MWe turbo-alternator sets, producing a maximum output of 1200 MWe, though net output is 1090 MWe after the effects of house load, and downrating the reactor output due to corrosion and vibration concerns.[13]

In March 2009, serious problems were found when Unit B21 was shut down for maintenance, and the reactor remained out of action for almost 18 months.[14][15] On 24 November 2009, a small fire in the boiler annexe of Unit B22 caused the second reactor to be shut down as well. Subsequently, Unit B22 has been intermittently shut down for up to several months at a time. Unit B21 was restarted in August 2010.[16][17][18] Unplanned shutdowns continued into 2011,[19][20] with B21 down for repairs from November 2011 to March 2012.[21]

In 2005, the station's accounting closure date was extended by ten years, which would allow it to continue operating until 2018, 35 years after first power generation.[22] In 2015, the plant was given another ten-year life extension, allowing an upgrade to control room computer systems and improved flood defences, taking the accounting closure date to 2028.[23]

Consideration of Dungeness C

On 15 April 2009, Dungeness was included in a list of 11 potential sites for new nuclear power stations, at the request of EDF Energy, which owns and operates Dungeness B.[24] The government did not include Dungeness C in its draft National Policy Statement published on 9 November 2009, citing environmental reasons and concerns about coastal erosion and associated flood risk.[25] The site was ruled out by Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change Chris Huhne in October 2010 with the former government's list of eleven potential sites reduced to eight.[26] Despite these environmental concerns, local Conservative MP Damian Collins, supported by some residents, lobbied Parliament to reconsider that position.[27][28]

HVDC station

From 1961 to 1984, Dungeness power station also housed the mercury arc valves of the static inverter plant converting AC into DC for transmission on HVDC Cross-Channel, the high-voltage direct current power cable carrying electric power across the English Channel to France. In 1983, a more powerful new inverter at Sellindge replaced this facility.

Ownership

Both stations were originally built, owned, and operated by the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB). Following privatisation of the electricity supply industry and the later part-privatisation of the nuclear power generating industry they are now owned by two different bodies: the original Magnox plant Dungeness A by the non-departmental government body the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) and newer AGR Dungeness B by EDF through British subsidiary EDF Energy.

Location

The stations are built on the largest area of open shingle in Europe, measuring 12 km by 6 km, which has been deposited by the sea and built up over thousands of years. The entire area is moving slowly north and east as the sea moves the shingle from one side of the headland to the other. It is surrounded by a nature reserve Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). A fleet of lorries is used to continuously maintain shingle sea defences for the plant as coastal erosion would otherwise move shingle away at an estimated rate of 6 m per year. Around 30,000 cubic metres of shingle are moved each year. It seems that deposition on the north shore of the headland does not keep pace with erosion, although the power stations are about 1 km to the west of that shore. In all, 90,000 cubic metres are moved each year along parts of the coast between Pett Level and Hythe. This is necessary for the safety of the entire area including the power stations. Around 100 million litres of cooling water are extracted and returned to the sea each hour, after being heated by 12 deg Celsius (22 deg F).

The position of the power station site on the headland over time is important. Geological history places the beginning of the promontory, some 3000 years ago, as shingle deposits offshore from Pett Level. From there the evidence suggests that the headland enlarged and migrated up Channel to its present position.

The headland and the coastline between Pett Level and Hythe are volatile. In recorded history Walland Marsh to the west of the power stations has been flooded.[29] In the space of sixty years severe inundation occurred, temporarily bringing the sea inland to Appledore and the original mouth of the River Rother from north of the headland at Romney to the south at Rye Harbour. The site is a few metres above Mean Sea Level and would be isolated in the event of flooding of the magnitude that submerged large areas of East Anglia and the Netherlands in 1953. It has been conjectured that the hurricane of 1987 did not bring the sea to the stations because there was a low tide at the time. Climate change could cause more frequent and powerful storms, and associated waves and surges are possible though not probable, and might increase the instability of the headland.[29]

In the media

A1 filmed the music video for their song Same Old Brand New You near the site of the power plant in 2000.

The station was used in the filming of the Doctor Who serial The Claws of Axos in January 1971.[30]

The beach was used in 2012 to test the Olympic torch.

The site provides a key plot point in the 2016 book, Alan Partridge: Nomad.[31]

See also

References

- ↑ "Dungeness B EDF Energy". Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Industcards.com". www.industcards.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- 1 2 The UK Magnox and AGR Power Station Projects

- 1 2 "Decommissioning progress at Dungeness A". World Nuclear News. World Nuclear Association. 21 January 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "Dungeness A turbine hall bites the dust". NDA. Nuclear Decommissioning Authority. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "Events - World Nuclear Association". www.world-nuclear.org.

- ↑ The Times, Tuesday, 10 December 1968; pg. 24; Issue 57430; col A

- ↑ The Times, Thursday, 11 March 1971; pg. 19; Issue 58119; col E

- ↑ The Times, Saturday, 4 November 1972; pg. 19; Issue 58623; col C

- ↑ The Times, Thursday, 6 November 1975; pg. 20; Issue 59546; col A

- ↑ The Times, Wednesday, 23 January 1980; pg. 3; Issue 60531; col E

- ↑ Walter C. Patterson (1985). Going Critical: An Unofficial History of British Nuclear Power (PDF). Paladin. ISBN 0-586-08516-5. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ↑ British Energy: Dungeness B Archived 1 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Dungeness B reactor back up after repairs". 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "No power from Dungeness for seven months so far". 11 February 2010.

- ↑ "Fire shuts nuclear power station". BBC. 24 November 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ↑ "One of two nuclear reactors back in action". 18 February 2009.

- ↑ "Dungeness reactor back online after repairs". 23 August 2010.

- ↑ "UPDATE 1-UK Hunterston B7 nuclear unit restarts Fri". Reuters. 5 March 2011.

- ↑ "UK Dungeness B22 unit back on grid since Jul 24-EDF". Reuters. 1 August 2011.

- ↑ "ABLE-UK nuclear power plant outages". Reuters. 25 November 2011.

- ↑ 10-year life extension at Dungeness B nuclear power station, British Energy, 15 September 2005, archived from the original on 22 March 2006, retrieved 19 June 2008

- ↑ "UK nuclear plant gets ten-year extension". World Nuclear News. 20 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "Dungeness among 11 sites for new nuclear power station". Kent and Sussex Courier. This is Kent. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "Press Release - Miliband sets strategic direction for overhaul of energy system". Department of Energy and Climate Change. 9 November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009.

- ↑ "Nuclear power: Eight sites identified for future plants". BBC News. 18 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ "Dungeness C: Third nuclear plant can be achieved, says MP". BBC News Online. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "2.37 pm Damian Collins (Folkestone and Hythe) (Con)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 27 May 2010. col. 355–357.

- 1 2 Eddison, J (2000). Romney Marsh Survival on a Frontier. Tempus. p. 139. ISBN 0-7524-1486-0.

- ↑ Mark Braxton (28 October 2009). "Doctor Who: The Claws of Axos". Radio Times. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Leith, Sam (23 December 2016). "Alan Partridge: Nomad review – bathos is everywhere, it's glorious". the Guardian.

Other sources

- Eddison, J (2000). Romney Marsh Survival on a Frontier. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1486-0. Page 139 also reports the 1990 flooding mentioned above. Page 139 also reports the 1990 flooding mentioned above.

- "Romney Marsh". Retrieved 5 February 2006.

- "Kent Against a Radioactive Environment". Archived from the original on 24 April 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- "British Energy". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2006.

- "industcards". Retrieved 16 April 2006.

- "Going Critical" (PDF). Retrieved 16 April 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dungeness Nuclear Power Station. |

- Dungeness A information page From the NDA.

- Dungeness B information page From EDF Energy.

- Kent Against a Radioactive Environment Local web site opposing the power stations.

- Photographs of Dungeness A From the British Nuclear Group image asset library.