Dollar

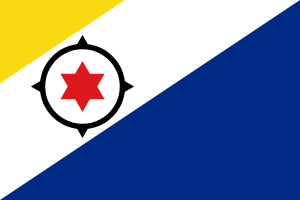

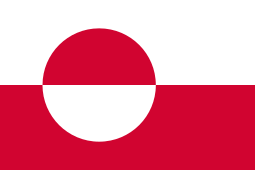

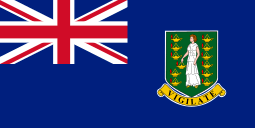

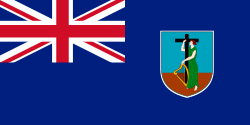

Dollar (often represented by the dollar sign $) is the name of more than 20 currencies, including those of Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Jamaica, Liberia, Namibia, New Zealand, Singapore, Taiwan, and the United States, whose US dollar is also the official currency of Caribbean Netherlands, East Timor, Ecuador, El Salvador, Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, Palau, Panama, and Zimbabwe.

One dollar is generally divided into 100 cents.

History

On 15 January 1520, the Czech Kingdom of Bohemia began minting coins from silver mined locally in Joachimsthal (Czech Jáchymov) and marked on reverse with the Czech lion. The coins were called joachimsthaler, which became shortened in common usage to thaler or taler. The German name "Joachimsthal" literally means "Joachim's valley" or "Joachim's dale". This name found its way into other languages: Czech and Slovenian tolar, Hungarian tallér, Danish and Norwegian (rigs) daler, Swedish (riks) daler, Icelandic dalur, Dutch (rijks) daalder or daler, Ethiopian ታላሪ ("talari"), Italian tallero, Greek τάλληρον, τάλιρο, tàlleron, tàliro, Polish talar, Persian dare, as well as – via Dutch – into English as dollar.[1]

A later Dutch coin also depicting a lion was called the leeuwendaler or leeuwendaalder, literally 'lion daler'. The Dutch Republic produced these coins to accommodate its booming international trade. The leeuwendaler circulated throughout the Middle East and was imitated in several German and Italian cities. This coin was also popular in the Dutch East Indies and in the Dutch New Netherland Colony (New York). It was in circulation throughout the Thirteen Colonies during the 17th and early 18th centuries and was popularly known as "lion (or lyon) dollar".[2][3] The currencies of Romania and Bulgaria are, to this day, 'lion' (leu/lev). The modern American-English pronunciation of dollar is still remarkably close to the 17th century Dutch pronunciation of daler.[4] Some well-worn examples circulating in the Colonies were known as "dog dollars".[5]

Spanish pesos – having the same weight and shape – came to be known as Spanish dollars.[4][6] By the mid-18th century, the lion dollar had been replaced by Spanish dollar, the famous "pieces of eight", which were distributed widely in the Spanish colonies in the New World and in the Philippines.[6][7][8][9][10]

Origins of the dollar sign

The sign is first attested in business correspondence in the 1770s as a scribal abbreviation "ps", referring to the Spanish American peso,[11][12] that is, the "Spanish dollar" as it was known in British North America. These late 18th- and early 19th-century manuscripts show that the s gradually came to be written over the p developing a close equivalent to the "$" mark, and this new symbol was retained to refer to the American dollar as well, once this currency was adopted in 1785 by the United States.[13][14][15][16][17]

Adoption by the United States

By the time of the American Revolution, Spanish dollars gained significance because they backed paper money authorized by the individual colonies and the Continental Congress.[7] Common in the Thirteen Colonies, Spanish dollars were even legal tender in one colony, Virginia.

On April 2, 1792, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton reported to Congress the precise amount of silver found in Spanish dollar coins in common use in the states. As a result, the United States dollar was defined[18] as a unit of pure silver weighing 371 4/16th grains (24.057 grams), or 416 grains of standard silver (standard silver being defined as 1,485 parts fine silver to 179 parts alloy).[19] It was specified that the "money of account" of the United States should be expressed in those same "dollars" or parts thereof. Additionally, all lesser-denomination coins were defined as percentages of the dollar coin, such that a half-dollar was to contain half as much silver as a dollar, quarter-dollars would contain one-fourth as much, and so on.

In an act passed in January 1837, the dollar's alloy (amount of non-silver metal present) was set at 15%. Subsequent coins would contain the same amount of pure silver as previously, but were reduced in overall weight (to 412.25 grains). On February 21, 1853, the quantity of silver in the lesser coins was reduced, with the effect that their denominations no longer represented their silver content relative to dollar coins.

Various acts have subsequently been passed affecting the amount and type of metal in U.S. coins, so that today there is no legal definition of the term "dollar" to be found in U.S. statute.[20][21][22] Currently the closest thing to a definition is found in United States Code Title 31, Section 5116, paragraph b, subsection 2: "The Secretary [of the Treasury] shall sell silver under conditions the Secretary considers appropriate for at least $1.292929292 a fine troy ounce." However, the dollar's constitutional meaning has remained unchanged through the years (see, United States Constitution).

Silver was mostly removed from U.S. coinage by 1965 and the dollar became a free-floating fiat currency without a commodity backing defined in terms of real gold or silver. The US Mint continues to make silver $1-denomination coins, but these are not intended for general circulation.

Relationship to the troy pound

The quantity of silver chosen in 1792 to correspond to one dollar, namely, 371.25 grains of pure silver, is very close to the geometric mean of one troy pound and one pennyweight. In what follows, "dollar" will be used as a unit of mass. A troy pound being 5760 grains and a pennyweight being 240 times smaller, or 24 grains, the geometric mean is, to the nearest hundredth, 371.81 grains. This means that the ratio of a pound to a dollar (15.52) roughly equals the ratio of a dollar to a pennyweight (15.47). These ratios are also very close to the ratio of a gram to a grain: 15.43. Finally, in the United States, the ratio of the value of gold to the value of silver in the period from 1792 to 1873 averaged to about 15.5, being 15 from 1792 to 1834 and around 16 from 1834 to 1873. This is also nearly the value of the gold to silver ratio determined by Isaac Newton in 1717.[23]

That these three ratios are all approximately equal has some interesting consequences. Let the gold to silver ratio be exactly 15.5. Then a pennyweight of gold, that is 24 grains of gold, is nearly equal in value to a dollar of silver (1 dwt of gold = $1.002 of silver). Second, a dollar of gold is nearly equal in value to a pound of silver ($1 of gold = 5754 3/8 grains of silver = 0.999 Lb of silver). Third, the number of grains in a dollar (371.25) roughly equals the number of grams in a troy pound (373.24).

The actual process of defining the US silver dollar had nothing to do with any geometric mean. The US government simply sampled all Spanish milled dollars in circulation in 1792 and arrived at the average weight in common use. And this was 371.25 grains of fine silver.

Usage in the United Kingdom

There are many quotes in the plays of William Shakespeare referring to dollars as money. Coins known as "thistle dollars" were in use in Scotland during the 16th and 17th centuries,[24] and use of the English word, and perhaps even the use of the coin, may have begun at the University of St Andrews. This might be supported by a reference to the sum of "ten thousand dollars" in Macbeth (act I, scene II) (an anachronism because the real Macbeth, upon whom the play was based, lived in the 11th century).

In 1804, a British five-shilling piece, or crown, was sometimes called "dollar". It was an overstruck Spanish eight real coin (the famous "piece of eight"), the original of which was known as a Spanish dollar. Large numbers of these eight-real coins were captured during the Napoleonic Wars, hence their re-use by the Bank of England. They remained in use until 1811.[25][26] During World War II, when the U.S. dollar was (approximately) valued at five shillings, the half crown (2s 6d) acquired the nickname "half dollar" in the UK.

Usage elsewhere

Chinese demand for silver in the 19th and early 20th centuries led several countries, notably the United Kingdom, United States and Japan, to mint trade dollars, which were often of slightly different weights from comparable domestic coinage. Silver dollars reaching China (whether Spanish, trade, or other) were often stamped with Chinese characters known as "chop marks", which indicated that that particular coin had been assayed by a well-known merchant and deemed genuine.

Other national currencies called “dollar”

Prior to 1873, the silver dollar circulated in many parts of the world, with a value in relation to the British gold sovereign of roughly $1 = 4s 2d (21p approx). As a result of the decision of the German Empire to stop minting silver thaler coins in 1871, in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, the worldwide price of silver began to fall.[27] This resulted in the U.S. Coinage Act (1873) which put the United States onto a 'de facto' gold standard. Canada and Newfoundland were already on the gold standard, and the result was that the value of the dollar in North America increased in relation to silver dollars being used elsewhere, particularly Latin America and the Far East. By 1900, value of silver dollars had fallen to 50 percent of gold dollars. Following the abandonment of the gold standard by Canada in 1931, the Canadian dollar began to drift away from parity with the U.S. dollar. It returned to parity a few times, but since the end of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates that was agreed to in 1944, the Canadian dollar has been floating against the U.S. dollar. The silver dollars of Latin America and South East Asia began to diverge from each other as well during the course of the 20th century. The Straits dollar adopted a gold exchange standard in 1906 after it had been forced to rise in value against other silver dollars in the region. Hence, by 1935, when China and Hong Kong came off the silver standard, the Straits dollar was worth 2s 4d (11.5p approx) sterling, whereas the Hong Kong dollar was worth only 1s 3d sterling (6p approx).

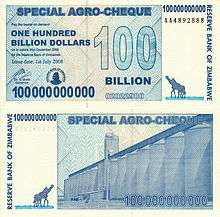

The term "dollar" has also been adopted by other countries for currencies which do not share a common history with other dollars. Many of these currencies adopted the name after moving from a £sd-based to a decimalized monetary system. Examples include the Australian dollar, the New Zealand dollar, the Jamaican dollar, the Cayman Islands dollar, the Fiji dollar, the Namibian dollar, the Rhodesian dollar, the Zimbabwe dollar, and the Solomon Islands dollar.

- The tala is based on the Samoan pronunciation of the word "dollar".

- The Slovenian tolar had the same etymological origin as dollar (that is, thaler).

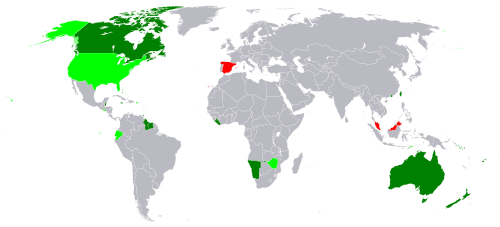

Economies that use a dollar

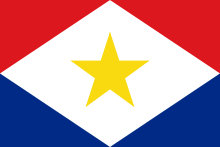

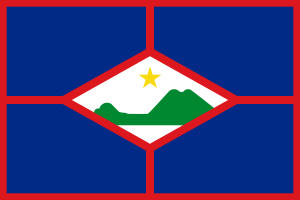

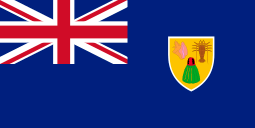

Other territories that use a dollar

Countries unofficially accepting a dollar

Countries and regions that have previously used the dollar

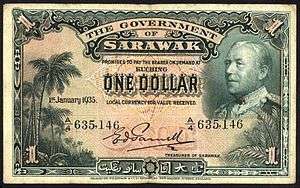

- Malaysia: the Malaysian ringgit used to be called the "Malaysian Dollar". The surrounding territories (that is, Malaya, British North Borneo, Sarawak, Brunei, and Singapore) used several varieties of dollars (for example, Straits dollar, Malayan dollar, Sarawak dollar, British North Borneo dollar; Malaya and British Borneo dollar) before Malaya, British North Borneo, Sarawak, Singapore and Brunei gained their independence from the United Kingdom. See also for a complete list of currencies.

- Spain: the Spanish dollar is closely related to the dollars and euros used today.

- Rhodesia: the Rhodesian dollar replaced the Rhodesian pound in 1970 and it was used until Zimbabwe came into being in 1980.

- Zimbabwe: once used the Zimbabwe dollar, but abolished it and now uses the South African rand, the US dollar,[32] the Euro, the Pound sterling, the Botswana pula, the Chinese yuan, the Indian rupee and the Japanese yen.[33]

See also

References

- ↑ "Why Is The Dollar Sign A Letter S?". Observation Deck. Retrieved 2015-02-09.

- ↑ Taxation in Colonial America. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Dutch Colonial – Lion Dollar". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- 1 2 "etymologiebank.nl". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Lion Dollar — Introduction". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- 1 2 Taxation in Colonial America. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- 1 2 Julian, R.W. (2007). "All About the Dollar". Numismatist: 41.

- ↑ Cross, Bill (2012). Dollar Default: How the Federal Reserve and the Government Betrayed Your Trust. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9781475261080.

- ↑ National Geographic. June 2002. p. 1. Ask Us.

- ↑ The First Modern Economy. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Lawrence Kinnaird (July 1976). "The Western Fringe of Revolution," The Western Historical Quarterly 7(3), 259. JSTOR 967081

- ↑ "Origin of Dollar Sign is Traced to Mexico", Popular Science, 116 (2): 59, 1930, ISSN 0161-7370

- ↑ Florian Cajori ([1929]1993). A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol. 2), 15-29.

- ↑ Arthur S. Aiton and Benjamin W. Wheeler (May 1931). "The First American Mint", The Hispanic American Historical Review 11(2), 198 and note 2 on 198. JSTOR 2506275

- ↑ Nussbaum, Arthur (1957). A History of the Dollar. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 56.

- ↑ Riesco Terrero, Ángel (1983). Diccionario de abreviaturas hispanas de los siglos XIII al XVIII: Con un apendice de expresiones y formulas juridico-diplomaticas de uso corriente. Salamanca: Imprenta Varona, 350. ISBN 84-300-9090-8

- ↑ Bureau of Engraving and Printing. "'What is the origin of the $ sign?' in FAQ Library". Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ↑ Act of April 2, A.D. 1792 of the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Section 9.

- ↑ Section 13 of the Act.

- ↑ United States Statutes at Large.

- ↑ Yeoman, RS. A Guide Book of United States Coins.

- ↑ Ewart, James E. Money — Ye shall have honest weights and measures.

- ↑ International Monetary Conference Held . . . in Paris in August 1878.

- ↑ Herbert Appold Grueber. Handbook of the Coins of Great Britain and Ireland in the British Museum.

- ↑ All Things Austen: An Encyclopedia of Austen's World ISBN 0-313-33034-4 p. 444

- ↑ kenelks.co.uk

- ↑ "Monetary Madhouse, Charles Savoie, 2005". Silver-investor.com. Retrieved 2012-03-25.

- ↑ Alongside Zimbabwean dollar (suspended indefinitely from 12 April 2009), Euro, Pound sterling, South African rand, Botswana pula, Australian dollar, Chinese yuan, Indian rupee and Japanese yen. The US Dollar has been adopted as the official currency for all government transactions.

- ↑ Wojtanik, Andrew (2005). Afghanistan to Zimbabwe. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. p. 147.

- ↑ Although called Panamanian balboas, US dollars circulate as official currency, since there are no Balboa bills, only coins that are the same size, weight and value as their US counterparts.

- ↑ Lankov, Andrei (2015). The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-939003-8.

- ↑ Adopted for all official government transactions

- ↑ Hungwe, Brian. "Zimbabwe’s multi-currency confusion", BBC News, Harare, 6 February 2014. Retrieved on 5 November 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dollar. |

- (in English) Etymonline (word history). for buck; Etymonline (word history) for dollar

- (in English) Currency converter. CNNMoney.com