£sd

£sd (pronounced /ɛlɛsˈdiː/ ell-ess-dee and occasionally written Lsd) is the popular name for the pre-decimal currencies once common throughout Europe, especially in the British Isles and hence in several countries of the British Empire and subsequently the Commonwealth. The abbreviation originates from the Latin currency denominations librae, solidi, and denarii.[1] In the United Kingdom, which was one of the last to abandon the system, these were referred to as pounds, shillings, and pence (pence being the plural of penny).

This system originated in the classical Roman Empire. It was re-introduced into Western Europe by Charlemagne, and was the standard for many centuries across the continent. In Britain, it was King Offa of Mercia who adopted the Frankish silver standard of librae, solidi and denarii in the late 8th century,[2] and the system was used in much of the British Commonwealth until the 1960s and 1970s, with Nigeria being the last to abandon it with the introduction of the naira on 1 January 1973.

Under this system, there were 12 pence in a shilling and 20 shillings, or 240 pence, in a pound. The penny was subdivided into 4 farthings until 31 December 1960, when they ceased to be legal tender in the UK, and until 31 July 1969 there were also halfpennies ("ha'pennies") in circulation. The advantage of such a system was its use in mental arithmetic, as it afforded many factors and hence fractions of a pound such as tenths, eighths, sixths and even sevenths and ninths if the guinea (worth 21 shillings) was used. When dealing with items in dozens, multiplication and division are straightforward; for example, if a dozen eggs cost four shillings, then each egg was priced at fourpence.

As countries of the British Empire became independent, some abandoned the £sd system quickly, while others retained it almost as long as the UK itself. Australia, for example, only changed to using a decimal currency on 14 February 1966. Still others, notably Ireland, decimalised only when the UK did. The UK abandoned the old penny on Decimal Day, 15 February 1971, when one pound sterling became divided into 100 new pence. This was a change from the system used in the earlier wave of decimalisations in Australia, New Zealand, Rhodesia and South Africa, in which the pound was replaced with a new major currency called either the "dollar" or the "rand". The British shilling was replaced by a 5 new pence coin worth one-twentieth of a pound.

For much of the 20th century, £sd was the monetary system of most of the Commonwealth countries, the major exceptions being Canada and India.

Historically, similar systems based on Roman coinage were used elsewhere; e.g., the division of the livre tournois in France and other pre-decimal currencies such as Spain, which had 20 maravedís to 1 real and 20 reals to 1 duro or 5 pesetas.[3]

Origins

In the classical Roman Empire, standard coinage was established to facilitate business transactions. 12 denarii were rated equal to 1 gold solidus – a 4th-century Roman coin that was rare but which still circulated; and, since 240 denarii were cut from one Roman libra of silver, 240 denarii therefore equalled one pound (livre in France, peso in Spain, etc.). Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, new currencies were introduced in Western Europe though (Eastern) Roman currencies remained popular. In the Eastern Roman Empire, the currencies gradually evolved away from the solidi and denarii.

In the eighth century, Charlemagne re-introduced and refined the system by decreeing that the money of the Holy Roman Empire should be the silver denarius, containing 22.5 grains of silver. As in the old Roman Empire, this had the advantage that any quantity of money could then be determined by counting (telling) coins rather than by weighing silver or gold.[4]

Different monetary systems based on units in ratio 20:1 & 12:1 (L:S & S:D) were widely used in Europe in medieval times.[5] The English name pound is a Germanic adaptation of the Latin phrase libra pondo 'a pound weight'.[6]

Writing conventions and pronunciations

There were several ways to represent amounts of money in writing, with no formal convention:

£2.3s.6d. (two pounds, three shillings and sixpence)

Unless there was cause to be punctilious, spoken: "two pound(s), three and six". Whether "pound" or "pounds" was used depended upon the speaker, varying with class, region and context.

1/- (one shilling, colloquially "a bob"; the slash sign derives from the older style of a long s for "solidus", which is also one name for the sign itself; the '-' is used in place of '0', meaning "zero pence").[7][8]

11d. (elevenpence)

1½d (a penny halfpenny, three halfpence – note that the lf in halfpenny and halfpence was always silent; they were pronounced "hayp'ny" /ˈheɪpni/ [9] and "haypence" /ˈheɪpəns/ [9][10] – hence the occasional spellings ha'penny and ha'pence)

2/- (two shillings, or one florin, colloquially "two-bob bit")

2/6 (two shillings and six pence, usually said as "two and six" or a "half-crown"; the value could also be spoken as "half a crown", but the coin was always a half-crown)

4/3 ("four and threepence", the latter word pronounced "thruppence" /ˈθrʌpəns/, "threppence" /ˈθrɛpəns/ or "throopence", -oo- as in "foot" /ˈθrʊpəns/, or "four-and-three")

5/- (five shillings, one crown, "five bob", a dollar)

£1.10s.- (one pound, ten shillings; one pound ten, "thirty bob")

£1/19/11¾d. (one pound, nineteen shillings and elevenpence three farthings: a psychological price, one farthing under £2)

£14.8s.2d (fourteen pounds, eight shillings and twopence – pronounced "tuppence" /ˈtʌpəns/ – in columns of figures. Commonly read "fourteen pound(s) eight and two")

Halfpennies and farthings (quarter of a penny) were represented by the appropriate symbol (¼ for farthing, ½ for halfpenny, or ¾ for three farthings) after the whole pence.

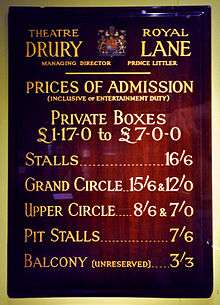

A convention frequently used in retail pricing was to list prices over one pound all in shillings, rather than in pounds and shillings; for example, £4-18-0 would be written as 98/- (£4.90 in decimal currency). This is still seen in shilling categories of Scottish beer, such as 90/- beer.

Sometimes, prices of luxury goods and furniture were expressed by merchants in guineas, although the guinea coin had not been struck since 1799. A guinea was 21 shillings (£1.05 in decimal currency). Professionals such as lawyers[11] and physicians, art dealers, and some others stated their fees in guineas rather than pounds, while, for example, salaries were stated in pounds per annum.[12] Historically, at some auctions, the purchaser would bid and pay in guineas but the seller would receive the same number of pounds; the commission was the same number of shillings. Tattersalls, the main auctioneer of racehorses in the United Kingdom and Ireland, continues this tradition of conducting auctions in guineas. The vendor's commission is 5%.[13] The word "guineas" is still found in the names of some British horse races, even though their prize funds are now fixed in pounds – such as the 1,000 Guineas and 2,000 Guineas at Newmarket Racecourse.

Colloquial terms

A threepenny bit (pronounced thrupney bit) was known as a "tickey" in South Africa[14] and Southern Rhodesia.[15] In Australia it was known as a tray (also spelt trey), or a tray bit, from the French "trois" meaning three.[16]

Fourpence was often known as a "groat", although the coin of that name was withdrawn in the 19th century.

A sixpenny bit was a "tanner", known in Australia as a "zack". One shilling was a "bob", and a pound a "nicker" or a "quid". The term "quid" is said to originate from the Latin phrase quid pro quo. A pound note was also sometimes called simply "a note" (e.g., "You owe me 50 notes").

A ten-shilling note was sometimes known as "half a bar".

A two-shillings-and-sixpence piece, in use until the introduction of decimal currency, was known as "half a crown" or "a half crown". Crown coins (with a value of five shillings) were latterly issued only as commemorative pieces.

A two-shilling piece known as a florin (an early attempt at decimalisation, being £ 1⁄10, and equal to 10 new pence after decimalisation) was in everyday use; it was referred to as "two bob", a "two-shilling bit", or a "two-bob-bit".

In popular culture

The currency of Lancre, a kingdom in the fictional world of Discworld, is a parody of the £sd system,.

The currency of knuts, sickles and galleons in the Harry Potter books is also a parody of the £sd system, with 29 knuts to a sickle and 17 sickles to a galleon.

Lysergic acid diethylamide was sometimes called "pounds, shillings and pence" during the 1960s, because of the abbreviation LSD.[17] The English rock group The Pretty Things released a 1966 single titled "£.s.d." that highlighted the double entendre.[18] The Chemical Defence Experimental Establishment called the first field trial with LSD as a chemical weapon "Moneybags" as a pun.[19]

The score of 26 at darts (one dart in each of the top three spaces) was sometimes called "half-a-crown" as late as the 1990s, though this did start to confuse the younger players. 26 is also referred to as "Breakfast", since 2/6 or half a crown was the standard cost for breakfast pre-decimalisation.

Today

Even today, and for all time,[20] bank notes that are no longer legal tender, including those that were issued pre-decimalisation, are exchangeable for their face value (regardless of the possible greater worth if sold or auctioned) if they are taken directly (or posted) to the Bank of England building in Threadneedle Street, London.[20] The last £sd coins to cease being legal tender in the UK after decimal day were the Sixpence (withdrawn 1980), the Shilling (withdrawn 1991) and the Florin (withdrawn 1993). In Australia, as of 2018, these coins can still be found in circulation occasionally as 5, 10 and 20 cent coins. The last £sd bank note to cease to be legal tender anywhere in the world was the Isle of Man ten shilling note, which ceased to be legal tender there in 2013.[21]

See also

- Pre-decimal British coinage

- Irish pre-decimal system

- Decimal Day for decimalisation in the UK and Ireland

- Decimalisation, for international decimalisation information

- Non-decimal currencies

References

- ↑ C. H. V. Sutherland, English Coinage 600-1900 (1973, ISBN 0-7134-0731-X), p. 10

- ↑ Hodgkin, Thomas (1906). The history of England … to the Norman conquest. London, New York and Bombay: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 234.

- ↑ Walkingame, Francis (1874). "The Tutor's Assistant": 96.

- ↑ Redish, Angela (2010). "From the Carolingian Penny to the Classical Gold Standard" (PDF). Bimetallism: An Economic and Historical Analysi. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02893-6. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ↑ Peter Spuffords (1986). Handbook of medieval exchange; Introduction.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. 'pound'

- ↑ "solidus: definition of solidus in Oxford dictionary (British & World English)". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2014-06-10. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- ↑ Fowler, Francis George. "long+s"+shilling The concise Oxford dictionary of current English. p. 829.

- 1 2 "halfpenny - definition of halfpenny in English from the Oxford dictionary". oxforddictionaries.com.

- ↑ "half", The Chambers Dictionary, p. 755, 1993, ISBN 0550102558

- ↑ John Palmer (1823). The Attorney and Agents new Table of Costs in the Courts of Kings Bench and Common Pleas, Fifth edition enlarged: to which is added a table of all the stamp duties. p. 461.

- ↑ Christine Evans-Pughe (12 December 2011). "Faraday - a man of contradictions". Engineering and Technology. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ "Guide to Sales (2007 Edition)" (PDF). Tattersalls Limited. Retrieved 24 July 2012. See also conditions of sale para 3.2 in the current catalogue

- ↑ Hear the Tickey Bottle Tinkle, The Rotarian, June 1954

- ↑ Southern Rhodesia, Past and Present, Chronicle Stationery and Book Store, 1945

- ↑ "Slang Terms for Money". The Australian Coin Collecting Blog. Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- ↑ Dickson, Paul (1998). Slang: The Authoritative Topic-By-Topic Dictionary of American Lingoes from All Walks of Life. Pocket Books. p. 134. ISBN 0-671-54920-0.

- ↑ http://www.theprettythings.com/disco.html The Pretty Things discography

- ↑ Andy Roberts (30 September 2008). Albion Dreaming: A popular history of LSD in Britain (Revised Edition with a new foreword by Dr. Sue Blackmore). Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. p. 52. ISBN 978-981-4328-97-5.

- 1 2 Bank of England. "Exchanging withdrawn Bank of England banknotes". Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ↑ "Withdrawal of Manx Plastic £1 note". Isle of Man Government. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to £sd. |

- £sd - Pounds, shillings, pence - Royal Mint Museum