Southeast Asia

.svg.png) | |

| Area | 4,545,792 km2 (1,755,140 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Population | 641,775,797 (3rd)[1] |

| Population density | 135.6/km2 (351/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | $2.557 trillion (exchange rate)[2] |

| GDP (PPP) | $7.6 trillion[3] |

| GDP per capita | $4,018 (exchange rate)[2] |

| HDI | 0.684 |

| Demonym | Southeast Asian |

| Countries | |

| Dependencies | |

| Languages |

Official languages

Other languages

|

| Time zones | |

| Largest cities |

Capital cities

|

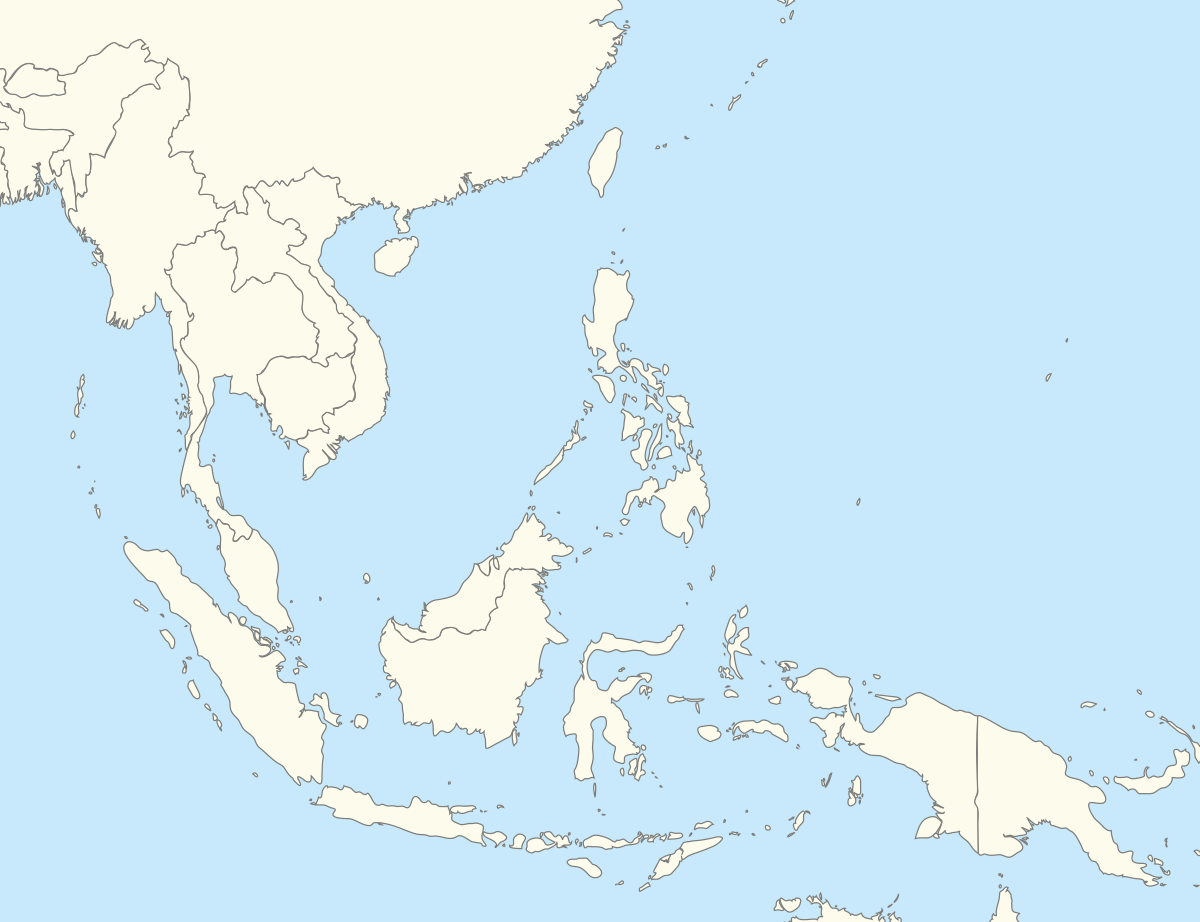

Southeast Asia or Southeastern Asia is a subregion of Asia, consisting of the countries that are geographically south of Japan and China, east of India, west of Papua New Guinea and north of Australia.[4] Southeast Asia is bordered to the north by East Asia, to the west by South Asia and Bay of Bengal, to the east by Oceania and Pacific Ocean, and to the south by Australia and Indian Ocean. The region is the only part of Asia that lies partly within the Southern Hemisphere, although the majority of it is in the Northern Hemisphere. In contemporary definition, Southeast Asia consists of two geographic regions:

- Mainland Southeast Asia, also known historically as Indochina, comprising parts of Eastern India (India stretches from South Asia to Southeast Asia), Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, and West Malaysia.

- Maritime Southeast Asia, also known historically as the East Indies and Malay Archipelago, comprising the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India, Indonesia, East Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, East Timor, Brunei, Christmas Island, and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Taiwan is also included by many anthropologists.

The region lies near the intersection of geological plates, with heavy seismic and volcanic activity. The Sunda Plate is the main plate of the region, featuring almost all Southeast Asian countries except Myanmar, northern Thailand, northern Vietnam, and northern Luzon of the Philippines. The mountain ranges in Myanmar, Thailand, and peninsular Malaysia are part of the Alpide belt, while the islands of the Philippines are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire. Both seismic belts meet in Indonesia, causing the region to have relatively high occurrences of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.[5]

Southeast Asia covers about 4.5 million km2 (1.7 million mi2), which is 10.5% of Asia or 3% of earth's total land area. Its total population is more than 641 million, about 8.5% of the world's population. It is the third most populous geographical region in the world after South Asia and East Asia. The region is culturally and ethnically diverse, with hundreds of languages spoken by different ethnic groups.[6] Ten countries in the region are members of ASEAN, a regional organisation established for economic, political, military, educational and cultural integration amongst its members.[7]

Definitions

The region, together with part of South Asia, was well known by the Europeans as the East Indies or simply the Indies until the 20th century. Chinese sources referred the region as 南洋 (Nanyang), which literally means the Southern Ocean. The mainland section of Southeast Asia was referred to as Indochina by European geographers due to its location between China and the Indian subcontinent and cultural influences from both neighboring regions. In the 20th century, however, the term became more restricted to former French Indochina territory (Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam). The maritime section of Southeast Asia is also known as Malay Archipelago, a term derived from the European concept of a Malay race.[8] Another term for Maritime Southeast Asia is Insulindia (Indian Islands), used to describe the region between Indochina and Australasia.[9]

The term "Southeast Asia" was first used in 1839 by an American pastor Howard Malcolm in his book entitled Travels in South-Eastern Asia. Malcolm only included the Mainland section and excluded the Maritime section in his definition of Southeast Asia.[10] The term was officially used in the midst of World War II by the Allies, through the formation of South East Asia Command (SEAC) in 1943.[11] SEAC popularised the use of the term "Southeast Asia", although what constituted Southeast Asia in the early days was not fixed, for example the Philippines and a large part of Indonesia were excluded by SEAC while Ceylon was included. However, by the late 1970s, a roughly standard usage of the term "Southeast Asia" and the territories it encompasses had emerged.[12] Although from a cultural or linguistic perspective, the definitions of "Southeast Asia" may vary, the most common definitions nowadays include the area represented by the countries (sovereign states and dependent territories) listed below.

Ten of eleven states of Southeast Asia are members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), while East Timor is an observer state. Papua New Guinea has stated that it might join ASEAN, and is currently an observer. Sovereignty issues exist over some territories in the South China Sea.

Some part of Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan (a disputed region or nation), are also considered as part of the Southeast Asia by some authors.[13][14][15]

Political divisions

Sovereign states

| State | Area (km2)[2] |

Population (2016)[1] |

Density (/km2) |

GDP (nominal), USD (2016)[2] |

GDP (PPP) per capita, Int$ (2016)[2] |

HDI (2016)[16]:22–24 | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5,765 | 423,196 | 78 | 10,458,000,000 | $76,884 | 0.865 | Bandar Seri Begawan | |

| 181,035 | 15,762,370 | 85 | 19,368,000,000 | $3,737 | 0.563 | Phnom Penh | |

| 14,874 | 1,268,671 | 75 | 2,501,000,000 | $4,187 | 0.605 | Dili | |

| 1,904,569 | 261,115,456 | 132 | 940,953,000,000 | $11,720 | 0.689 | Jakarta | |

| 236,800 | 6,758,353 | 30 | 13,761,000,000 | $5,710 | 0.586 | Vientiane | |

| 329,847 | 31,187,265 | 91 | 302,748,000,000 | $27,267 | 0.789 | Kuala Lumpur * | |

| 676,000 | 52,885,223 | 98 | 68,277,000,000 | $5,832 | 0.556 | Nay Pyi Daw | |

| 343,448 | 103,320,222 | 294 | 311,687,000,000 | $7,728 | 0.682 | Manila | |

| 724 | 5,622,455 | 7,671 | 296,642,000,000 | $90,151 | 0.925 | ||

| 513,120 | 68,863,514 | 127 | 390,592,000,000 | $16,888 | 0.740 | Bangkok | |

| 331,210 | 94,569,072 | 279 | 200,493,000,000 | $6,429 | 0.683 | Hanoi |

* Administrative centre in Putrajaya.

Dependent territories

| Territory | Area (km2) | Population | Density (/km2) | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 135[18] | 1,402[18] | 10.4 | Flying Fish Cove | |

| 14[19] | 596[19] | 42.6 | West Island (Pulau Panjang) |

Administrative subdivisions

| Territory | Area (km2) | Population | Density (/km2) | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8,251 | 379,944[20] | 46 | Port Blair | |

Geographical divisions

Southeast Asia is geographically divided into two subregions, namely Mainland Southeast Asia (or Indochina) and Maritime Southeast Asia (or the similarly defined Malay Archipelago) (Javanese: Nusantara).

Mainland Southeast Asia includes:

Maritime Southeast Asia includes:

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India are geographically considered part of Maritime Southeast Asia. Eastern Bangladesh and Northeast India have strong cultural ties with Southeast Asia and sometimes considered both South Asian and Southeast Asian.[21] Sri Lanka has on some occasions been considered a part of Southeast Asia because of its cultural ties to mainland Southeast Asia.[12][22] The rest of the island of New Guinea which is not part of Indonesia, namely, Papua New Guinea, is sometimes included, and so are Palau, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands, which were all part of the Spanish East Indies with strong cultural and linguistic ties to the region.[23]

The eastern half of Indonesia and East Timor (east of the Wallace Line) are considered to be biogeographically part of Oceania (Wallacea) due to its distinctive faunal features. New Guinea and its surrounding islands are geologically considered as a part of Australian continent, connected via the Sahul Shelf.

History

Prehistory

The region was already inhabited by Homo erectus from 1,000,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene age.[24] Homo sapiens reached the region by around 45,000 years ago,[25] having moved eastwards from the Indian subcontinent.[26] Homo floresiensis also lived in the area up until 12,000 years ago, when they became extinct.[27] It has been proposed that the Austronesian people, who form the majority of the modern population in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, East Timor, and the Philippines, may have migrated to Southeast Asia from Taiwan. They arrived in Indonesia around 2000 BC, and as they spread through the archipelago, they often settled along coastal areas and confined indigenous peoples such as Orang Asli of peninsular Malaysia, Negritos of the Philippines or Papuans of New Guinea to inland regions.[28] Archaeologists refer these people as Deutero-Malays, whom are more advanced in farming techniques and metal knowledge than their indigenous counterpart, the Proto-Malays.[29][30]

Studies presented by HUGO (Human Genome Organization) through genetic studies of the various peoples of Asia, show empirically that there was a single migration event from Africa, whereby the early people travelled along the south coast of Asia, first entered the Malay peninsula 50,000–90,000 years ago. The Orang Asli, in particular the Semang who show Negrito characteristics, are the direct descendants of these earliest settlers of Southeast Asia. These early people diversified and travelled slowly northwards to China, and the populations of Southeast Asia show greater genetic diversity than the younger population of China.[31][30] Studies on the genetics of modern Malays however show that there is a complex history of admixture of human populations in Southeast Asia, with the Malay population showing four major ancestral components: Austronesian, Proto-Malay, East Asian, and South Asian.[32]

Solheim and others have shown evidence for a Nusantao (Nusantara) maritime trading network ranging from Vietnam to the rest of the archipelago as early as 5000 BC to 1 AD.[33] The Bronze Age Dong Son culture flourished in Northern Vietnam from about 1000 BC to 1 BC. Its influence spread to other parts Southeast Asia.[34][35][36] The region entered the Iron Age era in 500 BC, when iron was forged also in northern Vietnam still under Dong Son, due to its frequent interactions with neighboring China.[24]

The peoples of Southeast Asia, especially those of Austronesian descent, have been seafarers for thousands of years, some reaching the island of Madagascar, became the ancestors of modern-day Malagasy people.[37] Passage through the Indian Ocean aided the colonisation of Madagascar, as well as commerce between Western Asia, eastern coast of India and Chinese southern coast.[37] Gold from Sumatra is thought to have reached as far west as Rome. Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History about Chryse and Argyre, two legendary islands rich in gold and silver, located in the Indian Ocean. Their vessels, such as the vinta, were capable to sail across ocean. Magellan's voyage records how much more manoeuvrable their vessels were, as compared to the European ships.[38] A slave from the Sulu Sea was believed to have been used in Magellan's voyage as a translator.

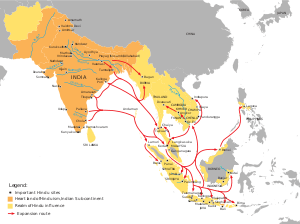

Most Southeast Asian people were originally animist, engaged in ancestors, nature, and spirits worship. These belief systems were later supplanted by Hinduism and Buddhism after the region, especially coastal areas, came under contacts with Indian subcontinent during the 1st century.[39] Indian Brahmins and traders brought Hinduism to the region and made contacts with local courts.[40] Local rulers converted to Hinduism or Buddhism and adopted Indian religious traditions to reinforce their legitimacy, elevate ritual status above their fellow chief counterparts and facilitate trade with South Asian states. They periodically invited Indian Brahmins into their realms and began a gradual process of Indianisation in the region.[41][42][43] Shaivism was the dominant religious tradition of many southern Indian Hindu kingdoms during the 1st century. It then spread into Southeast Asia via Bay of Bengal, Indochina, then Malay Archipelago, leading to thousands of Shiva temples on the islands of Indonesia as well as Cambodia and Vietnam, co-evolving with Buddhism in the region.[44][45] Theravada Buddhism entered the region during the 3rd century, via maritime trade routes between the region and Sri Lanka.[46] Buddhism later established a strong presence in Funan region in the 5th century. In present-day mainland Southeast Asia, Theravada is still the dominant branch of Buddhism, practiced by the Thai, Burmese and Cambodian Buddhists. This branch was fused with the Hindu-influenced Khmer culture. Mahayana Buddhism established presence in Maritime Southeast Asia, brought by Chinese monks during their transit in the region en route to Nalanda.[41] It is still the dominant branch of Buddhism practiced by Indonesian and Malaysian Buddhists.

The spread of these two Indian religions confined the adherents of Southeast Asian indigenous beliefs into remote inland areas. Maluku Islands and New Guinea were never been Indianised and its native people were predominantly animists until the 15th century when Islam began to spread in those areas.[47] While in Vietnam, Buddhism never managed to develop strong institutional networks due to strong Chinese influence.[48] In present-day Southeast Asia, Vietnam is the only country where its folk religion makes up the plurality.[49][50] Recently, Vietnamese folk religion is undergoing a revival with the support of the government.[51] Elsewhere, there are ethnic groups in Southeast Asia that resist conversion and still retain their original animist beliefs, such as the Dayaks in Kalimantan, the Igorots in Luzon, and the Shans in eastern Myanmar.[52]

Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms era

After the region came under contacts with Indian subcontinent circa 400 BCE, it began a gradual process of Indianisation where Indian ideas such as religions, cultures, architectures and political administrations were brought by traders and religious figures and adopted by local rulers. In turn, Indian Brahmins and monks were invited by local rulers to live in their realms and help transforming local polities to become more Indianised, blending Indian and indigenous traditions.[53][42][43] Sanskrit and Pali became the elite language of the region, which effectively made Southeast Asia part of the Indosphere.[54] Most of the region had been Indianised during the first centuries, while the Philippines later Indianised circa 9th century when Kingdom of Tondo was established in Luzon.[55] Vietnam, especially its northern part, was never fully Indianised due to the many periods of Chinese domination it experienced.[56]

The first Indian-influenced polities established in the region were the Pyu city-states that already existed circa 2nd century BCE, located in inland Myanmar. It served as an overland trading hub between India and China.[57] Theravada Buddhism was the predominant religion of these city states, while the presence of other Indian religions such as Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism were also widespread.[58][59] In the 1st century, the Funan states centered in Mekong Delta were established, encompassed modern-day Cambodia, southern Vietnam, Laos, and eastern Thailand. It became the dominant trading power in mainland Southeast Asia for about five centuries, provided passage for Indian and Chinese goods and assumed authority over the flow of commerce through Southeast Asia.[37] In maritime Southeast Asia, the first recorded Indianised kingdom was Salakanagara, established in western Java circa 2nd century CE. This Hindu kingdom was known by the Greeks as Argyre (Land of Silver).[60]

By the 5th century CE, trade networking between East and West was concentrated in the maritime route. Foreign traders were starting to use new routes such as Malacca and Sunda Strait due to the development of maritime Southeast Asia. This change resulted in the decline of Funan, while new maritime powers such as Srivijaya, Tarumanagara, and Medang emerged. Srivijaya especially became the dominant maritime power for more than 5 centuries, controlling both Strait of Malacca and Sunda Strait.[37] This dominance started to decline when Srivijaya were invaded by Chola Empire, a dominant maritime power of Indian subcontinent, in 1025.[61] The invasion reshaped power and trade in the region, resulted in the rise of new regional powers such as the Khmer Empire and Kahuripan.[62] Continued commercial contacts with the Chinese Empire enabled the Cholas to influence the local cultures. Many of the surviving examples of the Hindu cultural influence found today throughout Southeast Asia are the result of the Chola expeditions.[63]

As Srivijaya influence in the region declined, The Hindu Khmer Empire experienced a golden age during the 11th to 13th century CE. The empire's capital Angkor hosts majestic monuments—such as Angkor Wat and Bayon. Satellite imaging has revealed that Angkor, during its peak, was the largest pre-industrial urban centre in the world.[64] The Champa civilisation was located in what is today central Vietnam, and was a highly Indianised Hindu Kingdom. The Vietnamese launched a massive conquest against the Cham people during the 1471 Vietnamese invasion of Champa, ransacking and burning Champa, slaughtering thousands of Cham people, and forcibly assimilating them into Vietnamese culture.[65]

During the 13th century CE, the region experienced Mongol invasions, affected areas such as Vietnamese coast, inland Burma and Java. In 1258, 1285 and 1287, the Mongols try to invade Đại Việt and Champa.[66] The invasions were unsuccessful, yet both Dai Viet and Champa agreed to become tributary states to Yuan dynasty to avoid further conflicts.[67] The Mongols also invaded Pagan Kingdom in Burma from 1277 to 1287, resulted in fragmentation of the Kingdom and rise of smaller Shan States ruled by local chieftains nominally submitted to Yuan dynasty.[68][69] However, in 1297, a new local power emerged. Myinsaing Kingdom became the real ruler of Central Burma and challenged the Mongol rule. This resulted in the second Mongol invasion of Burma in 1300, which was repulsed by Myinsaing.[70][71] The Mongols would later in 1303 withdrawn from Burma.[72] In 1292, The Mongols sent envoys to Singhasari Kingdom in Java to ask for submission to Mongol rule. Singhasari rejected the proposal and injured the envoys, enraged the Mongols and made them sent a large invasion fleet to Java. Unbeknownst to them, Singhasari collapsed in 1293 due to a revolt by Kadiri, one of its vassals. When the Mongols arrived in Java, a local prince named Raden Wijaya offered his service to assist the Mongols in punishing Kadiri. After Kadiri was defeated, Wijaya turned on his Mongol allies, ambushed their invasion fleet and forced them to immediately leave Java.[73][74]

After the departure of the Mongols, Wijaya established the Majapahit Empire in eastern Java in 1293. Majapahit would soon grew into a regional power. Its greatest ruler was Hayam Wuruk, whose reign from 1350 to 1389 marked the empire's peak when other kingdoms in the southern Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Sumatra, and Bali came under its influence. Various sources such as the Nagarakertagama also mention that its influence spanned over parts of Sulawesi, Maluku, and some areas of western New Guinea and southern Philippines, making it one of the largest empire to ever exist in Southeast Asian history.[75](p107) By the 15th century CE however, Majapahit's influence began to wane due to many war of successions it experienced and the rise of new Islamic states such as Samudera Pasai and Malacca Sultanate around the strategic Strait of Malacca. Majapahit then collapsed around 1500. It was the last major Hindu kingdom and the last regional power in the region before the arrival of the Europeans.[76][77]

Spread of Islam

.jpg)

Islam began to made contacts with Southeast Asia in the 8th-century CE, when the Umayyads established trade with the region via sea routes.[78][79][80] However its spread into the region happened centuries later. In the 11th century, a turbulent period occurred in the history of Maritime Southeast Asia. The Indian Chola navy crossed the ocean and attacked the Srivijaya kingdom of Sangrama Vijayatungavarman in Kadaram (Kedah); the capital of the powerful maritime kingdom was sacked and the king was taken captive. Along with Kadaram, Pannai in present-day Sumatra and Malaiyur and the Malayan peninsula were attacked too. Soon after that, the king of Kedah Phra Ong Mahawangsa became the first ruler to abandon the traditional Hindu faith, and converted to Islam with the Sultanate of Kedah established in 1136. Samudera Pasai converted to Islam in 1267, the King of Malacca Parameswara married the princess of Pasai, and the son became the first sultan of Malacca. Soon, Malacca became the center of Islamic study and maritime trade, and other rulers followed suit. Indonesian religious leader and Islamic scholar Hamka (1908–1981) wrote in 1961: "The development of Islam in Indonesia and Malaya is intimately related to a Chinese Muslim, Admiral Zheng He."[81]

There are several theories to the Islamisation process in Southeast Asia. Another theory is trade. The expansion of trade among West Asia, India and Southeast Asia helped the spread of the religion as Muslim traders from Southern Yemen (Hadramout) brought Islam to the region with their large volume of trade. Many settled in Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia. This is evident in the Arab-Indonesian, Arab-Singaporean, and Arab-Malay populations who were at one time very prominent in each of their countries. Finally, the ruling classes embraced Islam and that further aided the permeation of the religion throughout the region. The ruler of the region's most important port, Malacca Sultanate, embraced Islam in the 15th century, heralding a period of accelerated conversion of Islam throughout the region as Islam provided a positive force among the ruling and trading classes. Gujarati Muslims played a pivotal role in establishing Islam in Southeast Asia.[82]

Trade and foreign colonisation

Trade among Southeast Asian countries has a long tradition. The consequences of colonial rule, struggle for independence and in some cases war influenced the economic attitudes and policies of each country until today.[83]

Chinese

From 111 BC to 938 AD northern Vietnam was under Chinese rule. Vietnam was successfully governed by a series of Chinese dynasties including the Han, Eastern Han, Eastern Wu, Cao Wei, Jin, Liu Song, Southern Qi, Liang, Sui, Tang, and Southern Han.

Records from Magellan's voyage show that Brunei possessed more cannon than European ships, so the Chinese must have been trading with them.[38]

Malaysian legend has it that a Chinese Ming emperor sent a princess, Hang Li Po, to Malacca, with a retinue of 500, to marry Sultan Mansur Shah after the emperor was impressed by the wisdom of the sultan. Han Li Po's well (constructed 1459) is now a tourist attraction there, as is Bukit Cina, where her retinue settled.

The strategic value of the Strait of Malacca, which was controlled by Sultanate of Malacca in the 15th and early 16th century, did not go unnoticed by Portuguese writer Duarte Barbosa, who in 1500 wrote "He who is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice".

European

Western influence started to enter in the 16th century, with the arrival of the Portuguese in Malacca, Maluku and the Philippines, the latter being settled by the Spanish years later. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries the Dutch established the Dutch East Indies; the French Indochina; and the British Strait Settlements. By the 19th century, all Southeast Asian countries were colonised except for Thailand.

European explorers were reaching Southeast Asia from the west and from the east. Regular trade between the ships sailing east from the Indian Ocean and south from mainland Asia provided goods in return for natural products, such as honey and hornbill beaks from the islands of the archipelago. Before the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the Europeans mostly were interested in expanding trade links. For the majority of the populations in each country, there was comparatively little interaction with Europeans and traditional social routines and relationships continued. For most, a life with subsistence level agriculture, fishing and, in less developed civilizations, hunting and gathering was still hard.[84]

Europeans brought Christianity allowing Christian missionaries to become widespread. Thailand also allowed Western scientists to enter its country to develop its own education system as well as start sending Royal members and Thai scholars to get higher education from Europe and Russia.

Japanese

During World War II, Imperial Japan invaded most of the former western colonies. The Shōwa occupation regime committed violent actions against civilians such as the Manila massacre and the implementation of a system of forced labour, such as the one involving 4 to 10 million romusha in Indonesia.[85] A later UN report stated that four million people died in Indonesia as a result of famine and forced labour during the Japanese occupation.[86] The Allied powers who defeated Japan in the South-East Asian theatre of World War II then contended with nationalists to whom the occupation authorities had granted independence.

Indian

Gujarat, India had a flourishing trade relationship with Southeast Asia in the 15th and 16th centuries.[82] The trade relationship with Gujarat declined after the Portuguese invasion of Southeast Asia in the 17th century.[82]

Contemporary history

Most countries in the region enjoy national autonomy. Democratic forms of government and the recognition of human rights are taking root. ASEAN provides a framework for the integration of commerce, and regional responses to international concerns.

China has asserted broad claims over the South China Sea, based on its Nine-Dash Line, and has built artificial islands in an attempt to bolster its claims. China also has asserted an exclusive economic zone based on the Spratly Islands. The Philippines challenged China in the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in 2013, and in Philippines v. China (2016), the Court ruled in favor of the Philippines and rejected China's claims.[87][88]

Geography

Indonesia is the largest country in Southeast Asia and it also the largest archipelago in the world by size (according to the CIA World Factbook). Geologically. the Indonesian archipelago is one of the most volcanically active regions in the world. Geological uplifts in the region have also produced some impressive mountains, culminating in Puncak Jaya in Papua, Indonesia at 5,030 metres (16,500 feet), on the island of New Guinea; it is the only place where ice glaciers can be found in Southeast Asia. The highest mountain in Southeast Asia is Hkakabo Razi at 5,967 meters and can be found in northern Burma sharing the same range of its parent peak, Mount Everest.

The South China Sea is the major body of water within Southeast Asia. The Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, and Singapore, have integral rivers that flow into the South China Sea.

Mayon Volcano, despite being dangerously active, holds the record of the world's most perfect cone which is built from past and continuous eruption.[89]

Boundaries

Southeast Asia is bounded to the southeast by the Australian continent, a boundary which runs through Indonesia. But a cultural touch point lies between Papua New Guinea and the Indonesian region of the Papua and West Papua, which shares the island of New Guinea with Papua New Guinea.

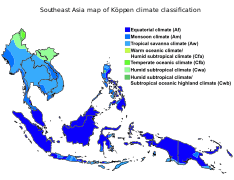

Climate

The climate in Southeast Asia is mainly tropical–hot and humid all year round with plentiful rainfall. Northern Vietnam and the Myanmar Himalayas are the only regions in Southeast Asia that feature a subtropical climate, which has a cold winter with snow. The majority of Southeast Asia has a wet and dry season caused by seasonal shift in winds or monsoon. The tropical rain belt causes additional rainfall during the monsoon season. The rain forest is the second largest on earth (with the Amazon being the largest). An exception to this type of climate and vegetation is the mountain areas in the northern region, where high altitudes lead to milder temperatures and drier landscape. Other parts fall out of this climate because they are desert like. Climate change will have a big effect on agriculture in Southeast Asia such as irrigation systems will be affected by changes in rainfall and runoff, and subsequently, water quality and supply.[90]

Environment

The vast majority of Southeast Asia falls within the warm, humid tropics, and its climate generally can be characterised as monsoonal. The animals of Southeast Asia are diverse; on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra, the orangutan, the Asian elephant, the Malayan tapir, the Sumatran rhinoceros and the Bornean clouded leopard can also be found. Six subspecies of the binturong or bearcat exist in the region, though the one endemic to the island of Palawan is now classed as vulnerable.

Tigers of three different subspecies are found on the island of Sumatra (the Sumatran tiger), in peninsular Malaysia (the Malayan tiger), and in Indochina (the Indochinese tiger); all of which are endangered species.

The Komodo dragon is the largest living species of lizard and inhabits the islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang in Indonesia.

The Philippine eagle is the national bird of the Philippines. It is considered by scientists as the largest eagle in the world,[91] and is endemic to the Philippines' forests.

The wild Asian water buffalo, and on various islands related dwarf species of Bubalus such as anoa were once widespread in Southeast Asia; nowadays the domestic Asian water buffalo is common across the region, but its remaining relatives are rare and endangered.

The mouse deer, a small tusked deer as large as a toy dog or cat, mostly can be found on Sumatra, Borneo (Indonesia) and in Palawan Islands (Philippines). The gaur, a gigantic wild ox larger than even wild water buffalo, is found mainly in Indochina. There is very little scientific information available regarding Southeast Asian amphibians.[92]

Birds such as the peafowl and drongo live in this subregion as far east as Indonesia. The babirusa, a four-tusked pig, can be found in Indonesia as well. The hornbill was prized for its beak and used in trade with China. The horn of the rhinoceros, not part of its skull, was prized in China as well.

The Indonesian Archipelago is split by the Wallace Line. This line runs along what is now known to be a tectonic plate boundary, and separates Asian (Western) species from Australasian (Eastern) species. The islands between Java/Borneo and Papua form a mixed zone, where both types occur, known as Wallacea. As the pace of development accelerates and populations continue to expand in Southeast Asia, concern has increased regarding the impact of human activity on the region's environment. A significant portion of Southeast Asia, however, has not changed greatly and remains an unaltered home to wildlife. The nations of the region, with only few exceptions, have become aware of the need to maintain forest cover not only to prevent soil erosion but to preserve the diversity of flora and fauna. Indonesia, for example, has created an extensive system of national parks and preserves for this purpose. Even so, such species as the Javan rhinoceros face extinction, with only a handful of the animals remaining in western Java.

The shallow waters of the Southeast Asian coral reefs have the highest levels of biodiversity for the world's marine ecosystems, where coral, fish and molluscs abound. According to Conservation International, marine surveys suggest that the marine life diversity in the Raja Ampat (Indonesia) is the highest recorded on Earth. Diversity is considerably greater than any other area sampled in the Coral Triangle composed of Indonesia, Philippines, and Papua New Guinea. The Coral Triangle is the heart of the world's coral reef biodiversity, the Verde Passage is dubbed by Conservation International as the world's "center of the center of marine shorefish biodiversity". The whale shark, the world's largest species of fish and 6 species of sea turtles can also be found in the South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean territories of the Philippines.

The trees and other plants of the region are tropical; in some countries where the mountains are tall enough, temperate-climate vegetation can be found. These rainforest areas are currently being logged-over, especially in Borneo.

While Southeast Asia is rich in flora and fauna, Southeast Asia is facing severe deforestation which causes habitat loss for various endangered species such as orangutan and the Sumatran tiger. Predictions have been made that more than 40% of the animal and plant species in Southeast Asia could be wiped out in the 21st century.[93] At the same time, haze has been a regular occurrence. The two worst regional hazes were in 1997 and 2006 in which multiple countries were covered with thick haze, mostly caused by "slash and burn" activities in Sumatra and Borneo. In reaction, several countries in Southeast Asia signed the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution to combat haze pollution.

The 2013 Southeast Asian Haze saw API levels reach a hazardous level in some countries. Muar experienced the highest API level of 746 on 23 June 2013 at around 7 am.[94]

Economy

Even prior to the penetration of European interests, Southeast Asia was a critical part of the world trading system. A wide range of commodities originated in the region, but especially important were spices such as pepper, ginger, cloves, and nutmeg. The spice trade initially was developed by Indian and Arab merchants, but it also brought Europeans to the region. First Spaniards (Manila galleon) and Portuguese, then the Dutch, and finally the British and French became involved in this enterprise in various countries. The penetration of European commercial interests gradually evolved into annexation of territories, as traders lobbied for an extension of control to protect and expand their activities. As a result, the Dutch moved into Indonesia, the British into Malaya and parts of Borneo, the French into Indochina, and the Spanish and the US into the Philippines. An economic effect of this imperialism was the shift in the production of commodities. For example, the rubber plantations of Malaysia, Java, Vietnam and Cambodia, the tin mining of Malaya, the rice fields of the Mekong Delta in Vietnam and Irrawaddy River delta in Burma, were a response to powerful market demands.[95]

The overseas Chinese community has played a large role in the development of the economies in the region. These business communities are connected through the bamboo network, a network of overseas Chinese businesses operating in the markets of Southeast Asia that share common family and cultural ties.[96] The origins of Chinese influence can be traced to the 16th century, when Chinese migrants from southern China settled in Indonesia, Thailand, and other Southeast Asian countries.[97] Chinese populations in the region saw a rapid increase following the Communist Revolution in 1949, which forced many refugees to emigrate outside of China.[96]

The region's economy greatly depends on agriculture; rice and rubber have long been prominent exports. Manufacturing and services are becoming more important. An emerging market, Indonesia is the largest economy in this region. Newly industrialised countries include Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines, while Singapore and Brunei are affluent developed economies. The rest of Southeast Asia is still heavily dependent on agriculture, but Vietnam is notably making steady progress in developing its industrial sectors. The region notably manufactures textiles, electronic high-tech goods such as microprocessors and heavy industrial products such as automobiles. Oil reserves in Southeast Asia are plentiful.

Seventeen telecommunications companies contracted to build the Asia-America Gateway submarine cable to connect Southeast Asia to the US[98] This is to avoid disruption of the kind recently caused by the cutting of the undersea cable from Taiwan to the US in the 2006 Hengchun earthquakes.

Tourism has been a key factor in economic development for many Southeast Asian countries, especially Cambodia. According to UNESCO, "tourism, if correctly conceived, can be a tremendous development tool and an effective means of preserving the cultural diversity of our planet."[99] Since the early 1990s, "even the non-ASEAN nations such as Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Burma, where the income derived from tourism is low, are attempting to expand their own tourism industries."[100] In 1995, Singapore was the regional leader in tourism receipts relative to GDP at over 8%. By 1998, those receipts had dropped to less than 6% of GDP while Thailand and Lao PDR increased receipts to over 7%. Since 2000, Cambodia has surpassed all other ASEAN countries and generated almost 15% of its GDP from tourism in 2006.[101]

Indonesia is the only member of G-20 major economies and is the largest economy in the region.[102] Indonesia's estimated gross domestic product for 2016 was US$932.4 billion (nominal) or $3,031.3 billion (PPP) with per capita GDP of US$3,604 (nominal) or $11,717 (PPP).[103]

Stock markets in Southeast Asia have performed better than other bourses in the Asia-Pacific region in 2010, with the Philippines' PSE leading the way with 22 percent growth, followed by Thailand's SET with 21 percent and Indonesia's JKSE with 19 percent.[104][105]

Southeast Asia's GDP per capita is US$3,853 according to a 2015 United Nations report, which is comparable to Guatemala and Tonga.[106]

| Country | Currency | Population (2017)[107] |

Nominal GDP (2017)[108] |

GDP per capita (2017)[109] |

GDP growth

(2017)[110] |

Inflation

(2017)[111] |

Main industries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B$ Brunei dollar | 443,593 | $12.743 billion | $29,712 | 0.5% | -0.1% | Petroleum, Petrochemicals, Fishing | |

| ៛ Riel | 16,204,486 | $22.252 billion | $1,390 | 6.9% | 2.9% | Clothing, Gold, Agriculture | |

| US$ US dollar | 1,291,358 | $2.610 billion | $2,104 | -0.5% | 0.6% | Petroleum, Coffee, Electronics | |

| Rp Rupiah | 260,580,739 | $1,015.411 billion | $3,876 | 5.1% | 3.8% | Coal, Petroleum, Palm oil | |

| ₭ Kip | 7,126,706 | $16.984 billion | $2,542 | 6.8% | 0.8% | Copper, Electronics, Tin | |

| RM Ringgit | 31,381,992 | $314.497 billion | $9,813 | 5.9% | 3.8% | Electronics, Petroleum, Palm oil | |

| K Kyat | 55,123,814 | $66.537 billion | $1,264 | 6.7% | 5.1% | Natural gas, Agriculture, Clothing | |

| ₱ Peso | 104,256,076 | $313.419 billion | $2,976 | 6.7% | 3.2% | Electronics, Timber, Automotive | |

| S$ Singapore dollar | 5,888,926 | $323.902 billion | $57,713 | 3.6% | 0.6% | Electronics, Petroleum, Chemicals | |

| ฿ Baht | 68,414,135 | $455.378 billion | $6,591 | 3.9% | 0.7% | Electronics, Automotive, Rubber | |

| ₫ Đồng | 96,160,163 | $220.408 billion | $2,354 | 6.8% | 3.5% | Electronics, Clothing, Agriculture |

Demographics

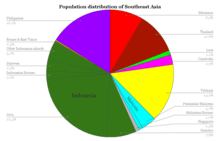

Southeast Asia has an area of approximately 4,500,000 km2 (1.7 million square miles). As of 2016, around 642 million people live in the region, more than a fifth live (143 million) on the Indonesian island of Java, the most densely populated large island in the world. Indonesia is the most populous country with 261 million people, and also the 4th most populous country in the world. The distribution of the religions and people is diverse in Southeast Asia and varies by country. Some 30 million overseas Chinese also live in Southeast Asia, most prominently in Christmas Island, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, and also as the Hoa in Vietnam. People of Southeast Asian origins are known as Southeast Asians or Aseanites.

Ethnic groups

The Aslians and Negritos were believed as one of the earliest inhabitant in the region. They are genetically related to the Papuans in Eastern Indonesia and Australian Aborigines. The next waves of human migration to Southeast Asia were Austroasiatic and Austronesians, which today forming the majority of the regional population.

In modern times, the Javanese are the largest ethnic group in Southeast Asia, with more than 100 million people, mostly concentrated in Java, Indonesia. The second largest ethnic group in Southeast Asia is Vietnamese with around 86 million population, mainly inhabit Vietnam forming significant minority in neighboring Cambodia and Laos. The Thais is also a significant ethnic group with around 59 million population forming the majority in Thailand. In Burma, the Burmese account for more than two-thirds of the ethnic stock in this country.

.jpg)

Indonesia is clearly dominated by the Javanese and Sundanese ethnic groups, with hundreds of ethnic minorities inhabited the archipelago, including Madurese, Minangkabau, Bugis, Balinese, Dayak, Batak and Malays. While Malaysia is split between more than half Malays and one-quarter Chinese, and also Indian minority in the West Malaysia however Dayaks is the most majority in Sarawak and Kadazan-dusun is the most majority in Sabah which are in the East Malaysia. The Malays are the majority in West Malaysia and Brunei, while they forming a significant minority in Indonesia, Southern Thailand, East Malaysia and Singapore. In city-state Singapore, Chinese are the majority, yet the city is a multicultural melting pot with Malays, Indians and Eurasian also called the island their home.

The Chams forming a significant minority in Central and South Vietnam, also in Central Cambodia. While the Khmers are the majority in Cambodia, and forming a significant minority in Southern Vietnam and Thailand. The Hmong people are the minority in Vietnam, China and Laos.

Within the Philippines, the Visayan (mainly Cebuanos and Hiligaynons), Tagalog, Ilocano, Bicolano and Central Luzon (mainly Kapampangan and Pangasinan) groups are significant.

Religion

Countries in Southeast Asia practice many different religions. By population, Islam is the most practised faith, numbering approximately 240 million adherents, or about 40% of the entire population, concentrated in Indonesia, Brunei, Malaysia, Southern Thailand and in the Southern Philippines. Indonesia is the most populous Muslim-majority country around the world.

Buddhism is predominant in Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Burma and Singapore. Ancestor worship and Confucianism are also widely practised in Vietnam and Singapore.

Christianity is predominant in the Philippines, eastern Indonesia, East Malaysia and East Timor. The Philippines has the largest Roman Catholic population in Asia. East Timor is also predominantly Roman Catholic due to a history of Portuguese rule.

No individual Southeast Asian country is religiously homogeneous. In the world's most populous Muslim nation, Indonesia, Hinduism is dominant on islands such as Bali. Christianity also predominates in the rest of the part of the Philippines, New Guinea and Timor. Pockets of Hindu population can also be found around Southeast Asia in Singapore, Malaysia etc. Garuda (Sanskrit: Garuḍa), the phoenix who is the mount (vahanam) of Vishnu, is a national symbol in both Thailand and Indonesia; in the Philippines, gold images of Garuda have been found on Palawan; gold images of other Hindu gods and goddesses have also been found on Mindanao. Balinese Hinduism is somewhat different from Hinduism practised elsewhere, as Animism and local culture is incorporated into it. Christians can also be found throughout Southeast Asia; they are in the majority in East Timor and the Philippines, Asia's largest Christian nation. In addition, there are also older tribal religious practices in remote areas of Sarawak in East Malaysia, Highland Philippines and Papua in eastern Indonesia. In Burma, Sakka (Indra) is revered as a nat. In Vietnam, Mahayana Buddhism is practised, which is influenced by native animism but with strong emphasis on ancestor worship.

The religious composition for each country is as follows: Some values are taken from the CIA World Factbook:[112]

| Country | Religions |

|---|---|

| Hinduism (69%), Christianity, Islam, Sikhism and others | |

| Islam (67%), Buddhism, Christianity, others (indigenous beliefs, etc.) | |

| Buddhism (89%), Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Animism, others | |

| Buddhism (97%), Islam, Christianity, Animism, others | |

| Buddhism (75%), Islam, Christianity | |

| Islam (80%), others | |

| Roman Catholicism (97%), Protestantism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism | |

| Islam (87.18%), Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, others[113] | |

| Buddhism (67%), Animism, Christianity, others | |

| Islam (60.4%), Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Animism | |

| Roman Catholicism (80%), Islam (11%),[114] Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ) (3%), Buddhism (2%),[115] Animism (1.25%), others (0.35%) | |

| Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Taoism, Hinduism, others | |

| Buddhism (93.83%), Islam (4.56%), Christianity (0.8%), Hinduism (0.011%), others (0.079%) | |

| Vietnamese folk religion (45.3%), Buddhism (16.4%), Christianity (8.2%), Other (0.4%), Unaffiliated (29.6%)[116] |

Languages

Each of the languages have been influenced by cultural pressures due to trade, immigration, and historical colonization as well. There are nearly over 800 native languages in the region.

The language composition for each country is as follows (with official languages in bold):

| Country | Languages |

|---|---|

| Bengali, Hindi, English, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Shompen, A-Pucikwar, Aka-Jeru, Aka-Bea, Aka-Bo, Aka-Cari, Aka-Kede, Aka-Kol, Aka-Kora, Aka-Bale, Jangil, Jarawa, Oko-Juwoi, Önge, Sentinelese, Camorta, Car, Chaura, Katchal, Nancowry, Southern Nicobarese, Teressa | |

| Malay, English, Indonesian, Chinese, Tamil and indigenous Bornean dialects (Iban, Murutic language, Lun Bawang,)[117] | |

| Burmese, English, Shan, Kayin(Karen), Rakhine, Kachin, Chin, Mon, Kayah, Chinese and other ethnic languages.[118] | |

| Khmer, Thai, English, French, Vietnamese, Cham, Chinese, others[119] | |

| English, Chinese, Malay[120] | |

| English, Cocos Malay[121] | |

| Tetum, Portuguese, Indonesian, English, Mambae, Makasae, Tukudede, Bunak, Galoli, Kemak, Fataluku, Baikeno, others[122] | |

| Indonesian, English, Javanese, Dutch, Sundanese, Batak, Minangkabau, Buginese, Banjar, Papuan, Dayak, Acehnese, Ambonese Balinese, Betawi, Madurese, Musi, Manado, Sasak, Makassarese, Batak Dairi, Karo, Mandailing, Jambi Malay, Mongondow, Gorontalo, Ngaju, Nias, North Moluccan, Uab Meto, Bima, Manggarai, Toraja-Sa'dan, Komering, Tetum, Rejang, Muna, Sumbawa, Bangka Malay, Osing, Gayo, Bungku-Tolaki languages, Moronene, Bungku, Bahonsuai, Kulisusu, Wawonii, Mori Bawah, Mori Atas, Padoe, Tomadino, Lewotobi, Tae', Mongondow, Lampung, Tolaki, Ma'anyan, Simeulue, Gayo, Buginese, Mandar, Minahasan, Enggano, Ternate, Tidore, Mairasi, East Cenderawasih Language, Lakes Plain Languages, Tor-Kwerba, Nimboran, Skou/Sko, Border languages, Senagi, Pauwasi, Mandarin, Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, Teochew, Tamil, Punjabi, Bengali, and Arabic.

Indonesia has over 700 languages in over 17,000 islands across the archipelago, making Indonesia the second most linguistically diverse country on the planet,[123] slightly behind Papua New Guinea. The official language of Indonesia is Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia), widely used in educational, political, economic, and other formal situations. In daily activities and informal situations, most Indonesians speak in their local language(s). For more details, see: Languages of Indonesia. | |

| Lao, Thai, Vietnamese, Hmong, Miao, Mien, Dao, Shan, French, English and others[124] | |

| Malaysian, English, Indonesian, Mandarin, Tamil, Kedah Malay, Sabah Malay, Brunei Malay, Kelantan Malay, Pahang Malay, Acehnese, Javanese, Minangkabau, Banjar, Buginese, Hakka, Cantonese, Hokkien, Teochew, Fuzhounese, Telugu, Bengali, Punjabi, Hindi, Sinhalese, Malayalam, Arabic, Brunei Bisaya, Okolod, Kota Marudu Talantang, Kelabit, Lotud, Terengganu Malay, Semelai, Thai, Iban, Kadazan, Dusun, Kristang, Bajau, Jakun, Mah Meri, Batek, Melanau, Semai, Temuan, Lun Bawang, Temiar, Penan, Tausug, Iranun, Lundayeh/Lun Bawang and others,[125] see: Languages of Malaysia | |

| Filipino, English, Spanish, Visayan (Aklanon, Cebuano, Kinaray-a, Capiznon, Hiligaynon, Waray, Masbateño, Romblomanon, Cuyonon, Surigaonon, Butuanon, Tausug) Ivatan, Ilocano, Ibanag, Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Bicolano, Sama-Bajaw, Maguindanao, Maranao, Chavacano

The Philippines has more than a hundred native languages, most without official recognition from the national government. Spanish and Arabic are on a voluntary and optional basis. Malaysian, Indonesian, Mandarin, Lan-nang (Hokkien), Cantonese, Hakka, Japanese and Korean are also spoken in the Philippines due to immigration, geographic proximity and historical ties. See: Languages of the Philippines | |

| English, Malay, Mandarin Chinese, Tamil, Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, Telugu, Malayalam, Punjabi, Hindi, Sinhalese, Indonesian, Javanese, Balinese, Singlish creole and others | |

| Thai, English, Teochew, Minnan, Hakka, Yuehai, Malay, Tamil, Bengali, Urdu, Arabic, Lao, Northern Khmer, Isan, Shan, Lue, Phutai, Mon, Mein, Hmong, Karen, Burmese and others[126] | |

| Vietnamese, English, Khmer, French, Cantonese, Hmong, Tai, Cham and others[127] |

Cities

- Jabodetabek (Jakarta/West Java/Banten),

- Metro Manila (Manila/Quezon City/Makati/Taguig/Pasay/Caloocan and 11 others),

- Bangkok Metropolitan Region (Bangkok/Nonthaburi/Samut Prakan/Pathum Thani/Samut Sakhon/Nakhon Pathom),

- Greater Kuala Lumpur/Klang Valley (Kuala Lumpur/Selangor),

- Greater Penang (Penang/Kedah/Perak),

- Ho Chi Minh City Metropolitan Area (Ho Chi Minh City/Vung Tau),

- Yangon Region (Yangon/Thanlyin),

- Hanoi Capital Region (Hanoi/Hai Phong/Ha Long),

- Gerbangkertosusila (Surabaya/Sidoarjo/Gresik/Mojokerto/Lamongan/Bangkalan),

- Greater Bandung Metropolitan Area (Bandung/Cimahi),

- Metro Cebu (Cebu City/Mandaue/Lapu-Lapu City/Talisay City and 11 others),

- Metro Davao (Davao City/Digos/Tagum/Island Garden City of Samal),

- Metro Iloilo-Guimaras (Iloilo City/Pavia/Oton/Leganes/Zarraga/San Miguel/Guimaras) ,

- Metro Cagayan de Oro (Cagayan de Oro/ El Salvador and 13 others)

- Phnom Penh City (Phnom Penh/Kandal),

Culture

The culture in Southeast Asia is very diverse: on mainland Southeast Asia, the culture is a mix of Burmese, Cambodian, Laotian and Thai (Indian) and Vietnamese (Chinese) cultures. While in Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Malaysia the culture is a mix of indigenous Austronesian, Indian, Islamic, Western, and Chinese cultures. Also Brunei shows a strong influence from Arabia. Singapore and Vietnam show more Chinese influence[128] in that Singapore, although being geographically a Southeast Asian nation, is home to a large Chinese majority and Vietnam was in China's sphere of influence for much of its history. Indian influence in Singapore is only evident through the Tamil migrants,[129] which influenced, to some extent, the cuisine of Singapore. Throughout Vietnam's history, it has had no direct influence from India – only through contact with the Thai, Khmer and Cham peoples.

Rice paddy agriculture has existed in Southeast Asia for thousands of years, ranging across the subregion. Some dramatic examples of these rice paddies populate the Banaue Rice Terraces in the mountains of Luzon in the Philippines. Maintenance of these paddies is very labour-intensive. The rice paddies are well-suited to the monsoon climate of the region.

Stilt houses can be found all over Southeast Asia, from Thailand and Vietnam, to Borneo, to Luzon in the Philippines, to Papua New Guinea. The region has diverse metalworking, especially in Indonesia. This include weaponry, such as the distinctive kris, and musical instruments, such as the gamelan.

Influences

The region's chief cultural influences have been from some combination of Islam, India, and China. Diverse cultural influence is pronounced in the Philippines, derived particularly from the period of the Spanish and American rule, contact with Indian-influenced cultures, and the Chinese and Japanese trading era.

As a rule, the peoples who ate with their fingers were more likely influenced by the culture of India, for example, than the culture of China, where the peoples ate with chopsticks; tea, as a beverage, can be found across the region. The fish sauces distinctive to the region tend to vary.

Arts

The arts of Southeast Asia have affinity with the arts of other areas. Dance in much of Southeast Asia includes movement of the hands as well as the feet, to express the dance's emotion and meaning of the story that the ballerina is going to tell the audience. Most of Southeast Asia introduced dance into their court; in particular, Cambodian royal ballet represented them in the early 7th century before the Khmer Empire, which was highly influenced by Indian Hinduism. Apsara Dance, famous for strong hand and feet movement, is a great example of Hindu symbolic dance.

Puppetry and shadow plays were also a favoured form of entertainment in past centuries, a famous one being Wayang from Indonesia. The arts and literature in some of Southeast Asia is quite influenced by Hinduism, which was brought to them centuries ago. Indonesia, despite conversion to Islam which opposes certain forms of art, has retained many forms of Hindu-influenced practices, culture, art and literature. An example is the Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppet) and literature like the Ramayana. The wayang kulit show has been recognized by UNESCO on November 7, 2003, as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

It has been pointed out that Khmer and Indonesian classical arts were concerned with depicting the life of the gods, but to the Southeast Asian mind the life of the gods was the life of the peoples themselves—joyous, earthy, yet divine. The Tai, coming late into Southeast Asia, brought with them some Chinese artistic traditions, but they soon shed them in favour of the Khmer and Mon traditions, and the only indications of their earlier contact with Chinese arts were in the style of their temples, especially the tapering roof, and in their lacquerware.

Music

Traditional music in Southeast Asia is as varied as its many ethnic and cultural divisions. Main styles of traditional music can be seen: Court music, folk music, music styles of smaller ethnic groups, and music influenced by genres outside the geographic region.

Of the court and folk genres, gong-chime ensembles and orchestras make up the majority (the exception being lowland areas of Vietnam). Gamelan and Angklung orchestras from Indonesia, Piphat /Pinpeat ensembles of Thailand and Cambodia and the Kulintang ensembles of the southern Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi and Timor are the three main distinct styles of musical genres that have influenced other traditional musical styles in the region. String instruments also are popular in the region.

On November 18, 2010, UNESCO officially recognized angklung as a Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, and encourage Indonesian people and government to safeguard, transmit, promote performances and to encourage the craftsmanship of angklung making.

Writing

The history of Southeast Asia has led to a wealth of different authors, from both within and without writing about the region.

Originally, Indians were the ones who taught the native inhabitants about writing. This is shown through Brahmic forms of writing present in the region such as the Balinese script shown on split palm leaf called lontar (see image to the left — magnify the image to see the writing on the flat side, and the decoration on the reverse side).

The antiquity of this form of writing extends before the invention of paper around the year 100 in China. Note each palm leaf section was only several lines, written longitudinally across the leaf, and bound by twine to the other sections. The outer portion was decorated. The alphabets of Southeast Asia tended to be abugidas, until the arrival of the Europeans, who used words that also ended in consonants, not just vowels. Other forms of official documents, which did not use paper, included Javanese copperplate scrolls. This material would have been more durable than paper in the tropical climate of Southeast Asia.

In Malaysia, Brunei, and Singapore, the Malay language is now generally written in the Latin script. The same phenomenon is present in Indonesian, although different spelling standards are utilised (e.g. 'Teksi' in Malay and 'Taksi' in Indonesian for the word 'Taxi').

The use of Chinese characters, in the past and present, is only evident in Vietnam and more recently, Singapore and Malaysia. The adoption of Chinese characters in Vietnam dates back to around 111BC, when it was occupied by the Chinese. A Vietnamese script called Chu nom used modified Chinese characters to express the Vietnamese language. Both classical Chinese and Chu Nom were used up until the early 20th century.

However, the use of the Chinese script has been in decline, especially in Singapore and Malaysia as the younger generations are in favour of the Latin Script.

See also

References

- 1 2 "World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision". ESA.UN.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". World Economic. IMF. Outlook Database, October 2016

- ↑ ASEAN Community in Figures (ACIF) 2013 (PDF) (6th ed.). Jakarta: ASEAN. Feb 2014. p. 1. ISBN 978-602-7643-73-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ Klaus Kästle (September 10, 2013). "Map of Southeast Asia Region". Nations Online Project. One World – Nations Online. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

Nations Online is an online destination guide with many aspects of the nations and cultures of the world: geography, economy, science, people, culture, environment, travel and tourism, government and history.

- ↑ Chester, Roy (2008-07-16). Furnace of Creation, Cradle of Destruction: A Journey to the Birthplace of Earthquakes, Volcanoes, and Tsunamis. AMACOM. ISBN 978-0814409206.

- ↑ Zide; Baker, Norman H.; Milton E. (1966). Studies in comparative Austroasiatic linguistics. Foreign Language Study.

- ↑ "ASEAN Member States". ASEAN.

- ↑ Wallace, Alfred Russel (1869). The Malay Archipelago. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 1.

- ↑ Lach; Van Kley, Donald F.; Edwin J (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226467689.

- ↑ Eliot, Joshua; Bickersteth, Jane; Ballard, Sebastian (1996). Indonesia, Malaysia & Singapore Handbook. New York City: Trade & Trade & Travel Publications.

- ↑ Park; King, Seung-Woo; Victor T. (2013). The Historical Construction of Southeast Asian Studies: Korea and Beyond. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814414586.

- 1 2 Emmerson, Donald K (1984). "Southeast Asia: What's in a Name?". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 15 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1017/S0022463400012182. JSTOR 20070562. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ↑ "香港是東南亞結腸腫瘤最高發區".

- ↑ "【东南亚之王】是台湾?香港?澳门?新加坡?".

- ↑ "中国高铁发展迅猛昆明将成东南亚"首都"".

- ↑ Global 2016 Human Development Report Overview – English (PDF). New York: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2017. pp. 22–24. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ↑ "United Nations Statistics Division- Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49)". United Nations Statistics Division. 6 May 2015. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- 1 2 "Christmas Islands". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- 1 2 "Cocos (Keeling) Islands". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ↑ Population data as per the Indian Census.

- ↑ Baruah, Sanjib (2005). Durable Disorder: Understanding the Politics of Northeast India. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Friborg, Bastian (2010). Southeast Asia: Myth or Reality pg 4.

- ↑ Inoue, Yukiko (2005). Teaching with Educational Technology in the 21st Century: The Case of the Asia-Pacific Region: The Case of the Asia-Pacific Region. Idea Group Inc (IGI). p. 5. ISBN 978-1-59140-725-6.

- 1 2 Bellwood, Peter (2017-04-10). First Islanders: Prehistory and Human Migration in Island Southeast Asia (1 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781119251545.

- ↑ Demeter, Fabrice; Shackelford, Laura L.; Bacon, Anne-Marie; Duringer, Philippe; Westaway, Kira; Sayavongkhamdy, Thongsa; Braga, José; Sichanthongtip, Phonephanh; Khamdalavong, Phimmasaeng (2012-09-04). "Anatomically modern human in Southeast Asia (Laos) by 46 ka". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (36): 14375–14380. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10914375D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208104109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3437904. PMID 22908291.

- ↑ Smithsonian (July 2008). "The Great Human Migration": 2.

- ↑ Morwood, M. J.; Brown, P.; Jatmiko; Sutikna, T.; Wahyu Saptomo, E.; Westaway, K. E.; Rokus Awe Due; Roberts, R. G.; Maeda, T.; Wasisto, S.; Djubiantono, T. (13 October 2005). "Further evidence for small-bodied hominins from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia". Nature. 437 (7061): 1012–1017. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1012M. doi:10.1038/nature04022. PMID 16229067.

- ↑ Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- ↑ Murdock, George Peter (1969). Studies in the science of society. Singapore: Books for Libraries Press. ISBN 9780836911572.

- 1 2 "Geneticist clarifies role of Proto-Malays in human origin". Malaysiakini. 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- ↑ "Genetic 'map' of Asia's diversity". BBC News. 11 December 2009.

- ↑ Deng, L; Hoh, B. P; Lu, D; Saw, W. Y; Twee-Hee Ong, R; Kasturiratne, A; De Silva, H. J; Zilfalil, B. A; Kato, N; Wickremasinghe, A. R; Teo, Y. Y; Xu, S (3 September 2015). "Dissecting the genetic structure and admixture of four geographical Malay populations". Science Reports. 5: 14375. Bibcode:2015NatSR...514375D. doi:10.1038/srep14375. PMC 585825. PMID 26395220.

- ↑ Solheim, Journal of East Asian Archaeology, 2000, 2:1–2, pp. 273–284(12)

- ↑ Vietnam Tours Archived 26 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Nola Cooke, Tana Li, James Anderson – The Tongking Gulf Through History – Page 46 2011 -"Nishimura actually suggested the Đông Sơn phase belonged in the late metal age, and some other Japanese scholars argued that, contrary to the conventional belief that the Han invasion ended Đông Sơn culture, Đông Sơn artifacts, ..."

- ↑ Vietnam Fine Arts Museum 2000 "... the bronze cylindrical jars, drums, Weapons and tools which were sophistically carved and belonged to the World-famous Đông Sơn culture dating from thousands of years; the Sculptures in the round, the ornamental architectural Sculptures ..."

- 1 2 3 4 Hall, Kenneth R. (2011-01-16). A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100–1500. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742567610.

- 1 2 Laurence Bergreen, Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe, HarperCollins Publishers, 2003, hardcover 480 pages, ISBN 0-06-621173-5

- ↑ Jan Gonda, The Indian Religions in Pre-Islamic Indonesia and their survival in Bali, in Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 3 Southeast Asia, Religions, p. 1, at Google Books, pp. 1–54

- ↑ Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- 1 2 Hall, Kenneth R. (2010). A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100–1500. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-6762-7.

- 1 2 Vanaik, Achin (1997). The Furies of Indian Communalism: Religion, Modernity, and Secularization. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-016-0.

- 1 2 Montgomery, Robert L. (2002). The Lopsided Spread of Christianity: Toward an Understanding of the Diffusion of Religions. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97361-2.

- ↑ Jan Gonda (1975). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 3 Southeast Asia, Religions. BRILL Academic. pp. 3–20, 35–36, 49–51. ISBN 978-90-04-04330-5.

- ↑ Peter Bisschop (2011), Shaivism, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Steadman, Sharon R. (2016). Archaeology of Religion: Cultures and Their Beliefs in Worldwide Context. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-43388-2.

- ↑ Timme, Elke (2005). A Presença Portuguesa nas Ilhas das Moluccas 1511 – 1605. GRIN Verlag. p. 3. ISBN 978-3-638-43208-5.

- ↑ Church, Peter (2017). A Short History of South-East Asia. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-06249-3.

- ↑ The Global Religious Landscape 2010. The Pew Forum.

- ↑ "Global Religious Landscape". The Pew Forum. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ Roszko, Edyta (2012-03-01). "From Spiritual Homes to National Shrines: Religious Traditions and Nation-Building in Vietnam". East Asia. 29 (1): 25–41. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.467.6835. doi:10.1007/s12140-011-9156-x. ISSN 1096-6838.

- ↑ Baldick, Julian (2013-06-15). Ancient Religions of the Austronesian World: From Australasia to Taiwan. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781780763668.

- ↑ Hall, Kenneth R. (2010). A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development, 100–1500. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-6762-7.

- ↑ Mahbubani, Kishore; Sng, Jeffery (2017). The ASEAN Miracle: A Catalyst for Peace. NUS Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-981-4722-49-0.

- ↑ Postma, Antoon (June 27, 2008). "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. 40 (2): 182–203.

- ↑ Viet Nam social sciences 2002 Page 42 Ủy ban khoa học xã hội Việt Nam – 2002 "The first period of cultural disruption and transformation: in and around the first millennium CE (that is, the period of Bac thuoc) all of Southeast Asia shifted into strong cultural exchanges with the outside world, on the one hand with Chinese ..."

- ↑ Malik, Preet (2015). My Myanmar Years: A Diplomat's Account of India's Relations with the Region. SAGE Publications. p. 28. ISBN 978-93-5150-626-3.

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 2005: 31–34

- ↑ Htin Aung 1967: 15–17

- ↑ Iguchi, Masatoshi (2017). Java Essay: The History and Culture of a Southern Country. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-78462-885-7.

- ↑ R. C. Majumdar (1961), "The Overseas Expeditions of King Rājendra Cola", Artibus Asiae 24 (3/4), pp. 338–342, Artibus Asiae Publishers

- ↑ Mukherjee, Rila (2011). Pelagic Passageways: The Northern Bay of Bengal Before Colonialism. Primus Books. p. 76. ISBN 978-93-80607-20-7.

- ↑ The great temple complex at Prambanan in Indonesia exhibit a number of similarities with the South Indian architecture. See Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. The CōĻas, 1935 pp 709

- ↑ Damian Evans; et al. (9 April 2009). "A comprehensive archaeological map of the world's largest preindustrial settlement complex at Angkor, Cambodia". PNAS. 104 (36): 14277–82. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10414277E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702525104. PMC 1964867. PMID 17717084. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ↑ Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-300-13793-4.

- ↑ Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A history of Vietnam: from Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-313-29622-2.

- ↑ Bulliet, Richard; Crossley, Pamela; Headrick, Daniel; Hirsch, Steven; Johnson, Lyman (2014). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 336. ISBN 978-1-285-96570-3.

- ↑ Hardiman, John Percy (1900). Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. superintendent, Government printing, Burma.

- ↑ Bernice Koehler Johnson (2009). The Shan: Refugees Without a Camp, an English Teacher in Thailand and Burma. Trinity Matrix Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-9817833-0-7.

- ↑ Kohn, George Childs (2013). Dictionary of Wars. Taylor & Francis. p. 446. ISBN 978-1-135-95501-4.

- ↑ Whiting, Marvin C. (2002). Imperial Chinese Military History: 8000 BC-1912 AD. iUniverse. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-595-22134-9.

- ↑ Hardiman, John Percy (1900). Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. superintendent, Government printing, Burma. ISBN 9780231500043.

- ↑ SarDesai, D. R. (2012). Southeast Asia: Past and Present. Avalon Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8133-4838-4.

- ↑ Rao, B. V. History of Asia. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-207-9223-4.

- ↑ John Miksic (1999). Ancient History. Indonesian Heritage Series. Vol 1. Archipelago Press / Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 9789813018266.

- ↑ Hipsher, Scott (2013). The Private Sector's Role in Poverty Reduction in Asia. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-85709-449-0.

- ↑ Federspiel, Howard M. (2007). Sultans, Shamans, and Saints: Islam and Muslims in Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3052-6.

- ↑ Hardt, Doug (2016). Who Was Muhammad?: An Analysis of the Prophet of Islam in Light of the Bible and the Quran. TEACH Services, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4796-0544-6.

- ↑ Anderson, James (2013-03-21). Daily Life Through Trade: Buying and Selling in World History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36325-2.

- ↑ Ayoub, Mahmoud (2013). Islam: Faith and History. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78074-452-0.

- ↑ Wang Ma, Rosey (2003). Chinese Muslims in Malaysia: History and Development. Center for Asia-Pacific Area Studies, Academia Sinica.

- 1 2 3 Prabhune, Tushar (December 27, 2011). "Gujarat helped establish Islam in SE Asia". Ahmedabad: The Times of India.

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ↑ Library of Congress, 1992, "Indonesia: World War II and the Struggle For Independence, 1942–50; The Japanese Occupation, 1942–45" Access date: 9 February 2007.

- ↑ John W. Dower War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1986; Pantheon; ISBN 0-394-75172-8)

- ↑ Joseph Chinyong Liow, What does the South China Sea ruling mean, and what's next?, Brookings Institution (July 12, 2016).

- ↑ Euan Graham, The Hague Tribunal's South China Sea Ruling: Empty Provocation or Slow-Burning Influence?, Lowy Institute for International Policy (August 18, 2016).

- ↑ Davis, Lee (1992). Natural disasters: from the Black Plague to the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo. New York, NY: Facts on File Inc.. pp. 300–301.

- ↑ "Climate Change Impacts - South East Asia". Archived from the original on 29 August 2017.

- ↑ "Climate Reality Watch Party 2016". 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Navjot S. Sodhi; Barry W. Brook (2006). Southeast Asian Biodiversity in Crisis. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-521-83930-3.

- ↑ Biodiversity wipeout facing Southeast Asia, New Scientist, 23 July 2003

- ↑ 2013 Southeast Asian haze#Air Pollution Index readings

- ↑ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- 1 2 Murray L Weidenbaum (1 January 1996). The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia. Martin Kessler Books, Free Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-684-82289-1.

- ↑ Murray L Weidenbaum (1 January 1996). The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia. Martin Kessler Books, Free Press. pp. 23–28. ISBN 978-0-684-82289-1.

- ↑ Sean Yoong (27 April 2007). "17 Firms to Build $500M Undersea Cable". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ↑ Background overview of The National Seminar on Sustainable Tourism Resource Management Archived 24 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine., Phnom Penh, 9–10 June 2003.

- ↑ Hitchcock, Michael, et al. Tourism in South-East Asia. New York: Routledge, 1993

- ↑ WDI Online

- ↑ What is the G-20 Archived 4 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine., www.g20.org. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Imf.org. 20 September 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ↑ "SE Asia Stocks-Jakarta, Manila hit record highs, others firm". Reuters. 27 September 2010.

- ↑ Bull Market Lifts PSE Index to Top Rank Among Stock Exchanges in Asia | Manila Bulletin. Mb.com.ph (24 September 2010). Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ National Accounts Main Aggregates Database, 2015, (Select all countries, "GDP, Per Capita GDP – US Dollars", and 2015 to generate table), United Nations Statistics Division. Accessed on 5 July 2017.

- ↑ "Country Comparison :: Population". CIA. July 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook (April 2017) – Nominal GDP". IMF. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook (April 2017) – Nominal GDP per capita". IMF. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook (April 2017) – Real GDP growth". IMF. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook (April 2017) – Inflation rate, average consumer prices". IMF. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ↑ "Field Listing – Religions". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ↑ Indonesia – The World Factbook

- ↑ "National Commission on Muslim Filipino". www.ncmf.gov.ph.

- ↑ BuddhaNet. "World Buddhist Directory – Presented by BuddhaNet.Net". buddhanet.info.

- ↑ "Table: Religious Composition by Country, in Percentages". 18 December 2012.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – Brunei. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Country: Myanmar (Burma)". Joshua Project.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – Cambodia. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – Christmas Island. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – East Timor. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Top 20 Countries by Number of Languages Spoken". www.vistawide.com. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – Laos. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – Malaysia. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – Thailand. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook – Vietnam. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001478/147804eb.pdf

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- Tiwari, Rajnish (2003): Post-crisis Exchange Rate Regimes in Southeast Asia (PDF), Seminar Paper, University of Hamburg.

- Rand, Nelson (2009). Conflict: Journeys through war and terror in SouthEast Asia. Dunboyne: Maverick House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-905379-54-5.

Further reading

- Osborne, Milton (2010; first published in 1979). Southeast Asia: An Introductory History Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74237-302-7

- Fletcher, Banister; Cruickshank, Dan (1996; first published in 1896). Sir Banister Fletcher's a History of Architecture, Architectural Press, 20th edition. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9. Cf. Part Four, Chapter 27.

- Farah, Paolo Davide (2015) Energy Investments and Environmental Concerns in Southeast Asia, in: Paolo Davide FARAH & Piercarlo ROSSI, ENERGY: POLICY, LEGAL AND SOCIAL-ECONOMIC ISSUES UNDER THE DIMENSIONS OF SUSTAINABILITY AND SECURITY, World Scientific Reference on Globalisation in Eurasia and the Pacific Rim, Imperial College Press (London, UK) & World Scientific Publishing, Nov. 2015.

External links

- Topography of Southeast Asia in detail (PDF) (previous version)

- Southeast Asian Archive at the University of California, Irvine at Archive.is (archived 12 December 2012)

- Southeast Asia Digital Library at Northern Illinois University

- "Documenting the Southeast Asian Refugee Experience", exhibit at the University of California, Irvine, Library at Archive.is (archived 25 February 2003)

- Southeast Asia Visions, a collection of historical travel narratives Cornell University Library Digital Collection

- Official website of the ASEAN Tourism Association

- Art of Island Southeast Asia, a full text exhibition catalogue from The Metropolitan Museum of Art