Cracked tooth syndrome

| Cracked tooth syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

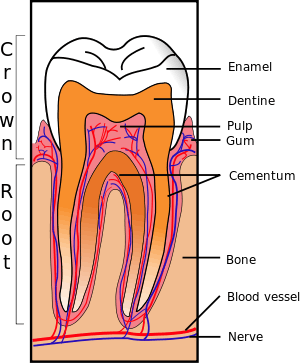

| Cross-section of a posterior tooth. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-9-CM | 521.81 |

Cracked tooth syndrome (abbreviated to CTS,[1] and also termed cracked cusp syndrome,[2] split tooth syndrome,[2] or incomplete fracture of posterior teeth),[2] is where a tooth has incompletely cracked but no part of the tooth has yet broken off. Sometimes it is described as a greenstick fracture.[2] The symptoms are very variable, making it a notoriously difficult condition to diagnose.

Classification and definition

Cracked tooth syndrome could be considered a type of dental trauma and also one of the possible causes of dental pain. One definition of cracked tooth syndrome is "a fracture plane of unknown depth and direction passing through tooth structure that, if not already involving, may progress to communicate with the pulp and/or periodontal ligament."[2]

Symptoms

The reported symptoms are very variable,[1] and frequently have been present for many months before the condition is diagnosed.[2] Reported symptoms may include some of the following:

- Sharp pain[2] when biting on a certain tooth,[1] which may get worse if the applied biting force is increased.[2] Sometimes the pain on biting occurs when the food being chewed is soft with harder elements, e.g. seeded bread.[1]

- "Rebound pain" i.e. sharp, fleeting pain occurring when the biting force is released from the tooth,[2] which may occur when eating fibrous foods.

- Pain when grinding the teeth backward and forward and side to side.[2]

- Sharp pain when drinking cold beverages or eating cold foods, lack of pain with heat stimuli.[2]

- Pain when eating or drinking sugary substances.[2]

- Sometimes the pain is well localized, and the individual is able to determine the exact tooth from which the symptoms are originating, but not always.[2]

Tooth crack in the upper first molar tooth in a patient who suffers from bruxism.

Tooth crack in the upper first molar tooth in a patient who suffers from bruxism.

If the crack propagates into the pulp, irreversible pulpitis, pulpal necrosis and periapical periodontitis may develop, with the respective associated symptoms.[2]

Pathophysiology

CTS is typically characterized by pain when releasing biting pressure on an object. This is because when biting down the segments are usually moving apart and thereby reducing the pressure in the nerves in the dentin of the tooth. When the bite is released the "segments" snap back together sharply increasing the pressure in the intradentin nerves causing pain. The pain is often inconsistent, and frequently hard to reproduce. If untreated, CTS can lead to severe pain, possible pulpal death, abscess, and even the loss of the tooth.

If the fracture propagates into the pulp, this is termed a complete fracture, and pulpitis and pulp death may occur. If the crack propagates further into the root, a periodontal defect may develop, or even a vertical root fracture.[2]

According to one theory, the pain on biting is caused by the 2 fractured sections of the tooth moving independently of each other, triggering sudden movement of fluid within the dentinal tubules.[2] This activates A-type nociceptors in the dentin-pulp complex, reported by the pulp-dentin complex as pain. Another theory is that the pain upon cold stimuli results from leak of noxious substances via the crack, irritating the pulp.[2]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome is notoriously difficult even for experienced clinicians.[1] The features are highly variable and may mimic sinusitis, temporomandibular disorders, headaches, ear pain, or atypical facial pain/atypical odontalgia (persistent idiopathic facial pain).[1] When diagnosing cracked tooth syndrome, a dentist takes many factors into consideration. A bite-test is commonly performed to confirm the diagnosis, in which the patient bites down on either a Q-tip, cotton roll, or an instrument called a Tooth Slooth.[3][4] Transillumination test can be helpful to identify the extension of the crack, also methylene blue dyes, although the dye may need a few days to show the trace of the propagation and it's colour may affect the aesthetics of the final resrotation.[5] Dental radiograph use is not reliable in identifying cracks as most cracks are very thin and they run in a (mesiodistal) horizontal direction rather than a vertical one.[5]

Epidemiology

[6] Aetiology of CTS is multifactorial, the causative factors include:

- previous restorative procedures.

- occlusal factors; patients who suffer from bruxism , or clenching are prone to have cracked teeth.

- developmental conditions/anatomical considerations.

- trauma

- others, e.g., aging dentition or presence of lingual tongue studs.

Most commonly involved teeth are mandibular molars followed by maxillary premolars, maxillary molars and maxillary premolars. in a recent audit, mandibular first molar thought to be most affected by CTS possibly due to the wedging effect of opposing pointy, protruding maxillary mesio-palatal cusp onto the mandibular molar central fissure. Studies have also found signs of cracked teeth following the cementation of porcelain inlays; it is suggested that the debonding of intracoronal restorations may be caused by unrecognized cracks in the tooth.[7]

Treatments

There is no universally accepted treatment strategy, but, generally, treatments aim to prevent movement of the segments of the involved tooth so they do not move or flex independently during biting and grinding and so the crack is not propagated.[8]

- Stabilization (core buildup) (a composite bonded restoration placed in the tooth or a band is placed around the tooth to minimize flexing)

- Crown restoration (to do the same as above but more permanently and predictably)

- Root Canal therapy (if pain persists after above)

- Extraction

History

The term "cuspal fracture odontalgia" was suggested in 1954 by Gibbs.[2] Subsequently, the term "cracked tooth syndrome" was coined in 1964 by Cameron,[1] who defined the condition as "an incomplete fracture of a vital posterior tooth that involves the dentin and occasionally extends into the pulp."[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mathew, S; Thangavel, B; Mathew, CA; Kailasam, S; Kumaravadivel, K; Das, A (Aug 2012). "Diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome". Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences. 4 (Suppl 2): S242–4. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.100219. PMC 3467890. PMID 23066261.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Banerji, S; Mehta, SB; Millar, BJ (May 22, 2010). "Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 1: aetiology and diagnosis". British Dental Journal. 208 (10): 459–63. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.449. PMID 20489766.

- ↑ The Cracked Tooth Syndrome (PDF), 68 (8), Canadian Dental Association, September 2002

- ↑ Patient Education about Cracked Teeth, Tooth Slooth, 12 December 2005

- 1 2 Banerji, S.; Mehta, S. B.; Millar, B. J. (2010-05). "Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 1: aetiology and diagnosis". British Dental Journal. 208 (10): 459–463. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.449. ISSN 0007-0610. PMID 20489766. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Banerji, S. (May 2017). "Programme Director, MSc Aesthetic Dentistry, Senior Clinical Teache". British Dental Journal. 222 (9): 659–666. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.398. PMID 28496251.

- ↑ Mathew, Sebeena; Thangavel, Boopathi; Mathew, Chalakuzhiyil Abraham; Kailasam, SivaKumar; Kumaravadivel, Karthick; Das, Arjun (2012-8). "Diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome". Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences. 4 (Suppl 2): S242–S244. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.100219. ISSN 0976-4879. PMC 3467890. PMID 23066261. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Banerji, S.; Mehta, S. B.; Millar, B. J. (12 June 2010). "Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 2: restorative options for the management of cracked tooth syndrome". BDJ. 208 (11): 503–514. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.496. PMID 20543791.