Cobalt(II) chloride

| |||

-chloride-3D-balls.png) Structure of anhydrous compound | |||

6forFeCoNi.png) Structure of hexahydrate | |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Cobalt(II) chloride | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.718 | ||

| EC Number | 231-589-4 | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number | GF9800000 | ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 3288 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| CoCl2 | |||

| Molar mass | 129.839 g/mol (anhydrous) 165.87 g/mol (dihydrate) 237.93 g/mol (hexahydrate) | ||

| Appearance | blue crystals (anhydrous) violet-blue (dihydrate) rose red crystals (hexahydrate) | ||

| Density | 3.356 g/cm3 (anhydrous) 2.477 g/cm3 (dihydrate) 1.924 g/cm3 (hexahydrate) | ||

| Melting point | 735 °C (1,355 °F; 1,008 K) (anhydrous) 140 °C (monohydrate) 100 °C (dihydrate) 86 °C (hexahydrate) | ||

| Boiling point | 1,049 °C (1,920 °F; 1,322 K) | ||

| 43.6 g/100 mL (0 °C) 45 g/100 mL (7 °C) 52.9 g/100 mL (20 °C) 105 g/100 mL (96 °C) | |||

| Solubility | 38.5 g/100 mL (methanol) 8.6 g/100 mL (acetone) soluble in ethanol, pyridine, glycerol | ||

| +12,660·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Structure | |||

| CdCl2 structure | |||

| hexagonal (anhydrous) monoclinic (dihydrate) Octahedral (hexahydrate) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 0783 | ||

| GHS pictograms |    | ||

| NFPA 704 | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) |

80 mg/kg (rat, oral) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other anions |

Cobalt(II) fluoride Cobalt(II) bromide Cobalt(II) iodide | ||

Other cations |

Rhodium(III) chloride Iridium(III) chloride | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Cobalt(II) chloride is an inorganic compound of cobalt and chlorine, with the formula CoCl2. It is usually supplied as the hexahydrate CoCl2·6H2O, which is one of the most commonly used cobalt compounds in the lab.[3]

The dihydrate is purple and hexahydrate is pink, whereas the anhydrous form is sky blue. Because of the ease of the hydration/dehydration reaction, and the resulting color change, cobalt chloride is used as an indicator for water in desiccants.

Niche uses of cobalt chloride include its role in organic synthesis and electroplating objects with cobalt metal.

Cobalt chloride has been classified as a substance of very high concern by the European Chemicals Agency as it is a suspected carcinogen.

Properties

Aqueous solutions of both CoCl2 and the hydrate contain the species [Co(H2O)6]2+. They also contain chloride ions. Solid CoCl2·6H2O consists of the molecule trans-[CoCl2(H2O)4] and two molecules of water of crystallization.[4] This species dissolves readily in water and alcohol. Concentrated aqueous solutions are red at room temperature but become blue at higher temperatures.[5] CoCl2·6H2O is deliquescent, and the anhydrous salt CoCl2 is hygroscopic.

Preparation

Hydrated cobalt chloride is prepared from cobalt(II) hydroxide or cobalt(II) carbonate and hydrochloric acid:

- CoCO3 + 2 HCl + 5 H2O → Co(H2O)6Cl2 + CO2

Upon heating, the hexahydrate dehydrates.[6] Dehydration can also be effected with trimethylsilyl chloride:[7]

- CoCl2•6H2O + 12 Me3SiCl → CoCl2 + 6 (Me3Si)2O + 12 HCl

Reactions

Generally, aqueous solutions of cobalt(II) chlorides behave like other cobalt(II) salts since these solutions consist of the [Co(H2O)6]2+ ion regardless of the anion. Such solutions give a precipitate of CoS upon treatment with H2S. CoCl2·6H2O and CoCl2 are weak Lewis acids. The adducts are usually either octahedral or tetrahedral. With pyridine (C

5H

5N), one obtains the octahedral complex:

- CoCl2·6H2O + 4 C5H5N → CoCl2(C5H5N)4 + 6 H2O

With triphenylphosphine (P(C

6H

5)

3), a tetrahedral complex results:

- CoCl2·6H2O + 2 P(C6H5)3 → CoCl2{P(C6H5)3}2 + 6 H2O

Salts of the anionic complex CoCl42− can be prepared using tetraethylammonium chloride:[8]

- CoCl2 + 2 [(C2H5)4N]Cl → [(C2H5)4N)]2[CoCl4]

The [CoCl4]2− ion is the blue ion that forms upon addition of hydrochloric acid to aqueous solutions of hydrated cobalt chloride, which are pink.

4.png)

In the laboratory, cobalt(II) chloride serves as a common precursor to other cobalt compounds. Reaction of the anhydrous compound with sodium cyclopentadienide gives cobaltocene. This 19-electron species is a good reducing agent, being readily oxidised to the yellow 18-electron cobaltacenium cation. Reaction of 1-norbonyllithium with the CoCl2·THF in pentane produces the brown, thermally stable cobalt(IV) tetralkyl[9][10] — a rare example of a stable transition metal/saturated alkane compound,[3] different products are obtained in other solvents.[11]

Co(III) derivatives

In the presence of ammonia or amines, cobalt(II) is readily oxidised by atmospheric oxygen to give a variety of cobalt(III) complexes. For example, the presence of ammonia triggers the oxidation of cobalt(II) chloride to hexamminecobalt(III) chloride:

- 4 CoCl2·6H2O + 4 NH4Cl + 20 NH3 + O2 → 4 [Co(NH3)6]Cl3 + 26 H2O

The reaction is often performed in the presence of charcoal as a catalyst, or hydrogen peroxide is employed in place of air. Other highly basic ligands including carbonate, acetylacetonate, and oxalate induce the formation of Co(III) derivatives. Simple carboxylates and halides do not.

Unlike Co(II) complexes, Co(III) complexes are very slow to exchange ligands, so they are said to be kinetically inert. The German chemist Alfred Werner was awarded the Nobel prize in 1913 for his studies on a series of these cobalt(III) compounds, work that led to an understanding of the structures of such coordination compounds.

Instability of CoCl3

_chloride.jpg)

The existence of cobalt(III) chloride, CoCl3, is disputed, although this compound is listed in some compendia.[12] According to Greenwood and Earnshaw, the only stable binary compounds of cobalt and the halogens, excluding CoF3, are the dihalides.[3] Stated differently, CoCl2 is unreactive toward Cl2. The stability of Co(III) in solution is considerably increased in the presence of ligands of greater Lewis basicity than chloride, such as amines. In other words, Co(II) is a stronger reductant when it has those ligands.

Safety

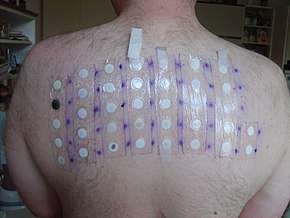

In 2005–06, cobalt chloride was the eighth-most-prevalent allergen in patch tests (8.4%).[13]

Other uses

- Invisible ink: when suspended in solution, cobalt(II) chloride can be made to appear invisible on a surface; when that same surface is subsequently exposed to significant heat (such as from a handheld heat gun or lighter) the ink permanently/ irreversibly changes to blue.

- Cobalt chloride is an established chemical inducer of hypoxia-like responses such as erythropoiesis.[14] Cobalt supplementation is not banned and therefore would not be detected by current anti-doping testing.[15] Cobalt chloride is a banned substance under the Australian Thoroughbred Racing Board.[16]

References

- ↑ "Cobalt muriate, CAS Number: 7646-79-9". www.chemindustry.com. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ↑ Santa Cruz Biotechnology: Cobalt(II) chloride

- 1 2 3 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ Wells, A. F. (1984), Structural Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-855370-6

- ↑ The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960.

- ↑ John Dallas Donaldson, Detmar Beyersmann, "Cobalt and Cobalt Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_281.pub2

- ↑ Philip Boudjouk, Jeung-Ho So (1992). "Solvated and Unsolvated Anhydrous Metal Chlorides from Metal Chloride Hydrates". Inorg. Synth. 29: 108–111. doi:10.1002/9780470132609.ch26.

- ↑ Gill, N. S. & Taylor, F. B. (1967). "Tetrahalo Complexes of Dipositive Metals in the First Transition Series". Inorg. Synth. 9: 136–142. doi:10.1002/9780470132401.ch37.

- ↑ Barton K. Bower & Howard G. Tennent (1972). "Transition metal bicyclo[2.2.1]hept-1-yls". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94 (7): 2512–2514. doi:10.1021/ja00762a056.

- ↑ Erin K. Byrne; Darrin S. Richeson & Klaus H. Theopold (1986). "Tetrakis(1-norbornyl)cobalt, a low spin tetrahedral complex of a first row transition metal". J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. (19): 1491–1492. doi:10.1039/C39860001491.

- ↑ Erin K. Byrne; Klaus H. Theopold (1989). "Synthesis, characterization, and electron-transfer reactivity of norbornyl complexes of cobalt in unusually high oxidation states". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111 (11): 3887–3896. doi:10.1021/ja00193a021.

- ↑ Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 71st edition, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1990.

- ↑ Zug KA, Warshaw EM, Fowler JF Jr, Maibach HI, Belsito DL, Pratt MD, Sasseville D, Storrs FJ, Taylor JS, Mathias CG, Deleo VA, Rietschel RL, Marks J. Patch-test results of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2005–2006. Dermatitis. 2009 May–Jun;20(3):149-60.

- ↑ W. Jelkmann: The disparate roles of cobalt in erythropoiesis, and doping relevance. Open Journal of Hematology, 2012, 3–6. http://rossscience.org/ojhmt/2075-907X-3-6.php

- ↑ Lippi G, Franchini M, Guidi GC (November 2005). "Cobalt chloride administration in athletes: a new perspective in blood doping?". Br J Sports Med. 39 (11): 872–3. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2005.019232. PMC 1725077. PMID 16244201.

- ↑ Bartley, Patrick (6 February 2015). "Cobalt crisis turns the eyes of the world onto Australian racing". The Sydney Morning Herald.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to cobalt(II) chloride. |