Chartwell

| Chartwell | |

|---|---|

|

"I bought Chartwell for that view" – Churchill on the view of the Weald of Kent that led him to buy the house[1] | |

| Type | House |

| Location | Westerham, Kent |

| Coordinates | 51°14′39″N 0°04′57″E / 51.244090°N 0.082450°ECoordinates: 51°14′39″N 0°04′57″E / 51.244090°N 0.082450°E |

| Built | 1923–4, with earlier origins |

| Architect | Philip Tilden |

| Architectural style(s) | Vernacular |

| Governing body | National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name: Chartwell | |

| Designated | 16 January 1975 |

| Reference no. | 1272626 |

Location of Chartwell in Kent | |

Chartwell is a country house near the town of Westerham, Kent in South East England. For over forty years it was the home of Winston Churchill. He bought the property in September 1922 and lived there until shortly before his death in January 1965. In the 1930s, when Churchill was excluded from political office, Chartwell became the centre of his world. At his dining table, he gathered those who could assist his campaign against German re-armament and the British government's response of appeasement; in his study, he composed speeches and wrote books; in his garden, he built walls, constructed lakes and painted. During the Second World War Chartwell was largely unused, the Churchills returning after he lost the 1945 election. In 1953, when again Prime Minister, the house became Churchill's refuge when he suffered a devastating stroke. In October 1964, he left for the last time, dying at his London home, 28, Hyde Park Gate, on 24 January 1965.

The origins of the estate reach back to the 14th century; in 1382 the property, then called Well-street, was sold by William-at-Well. It passed through various owners and in 1836 was auctioned, as a substantial, brick-built manor. In 1848, it was purchased by John Campbell Colquhoun, whose grandson sold it to Churchill. The Campbell Colquhouns greatly enlarged the house and the advertisement for its sale at the time of Churchill's purchase described it as an "imposing" mansion. Between 1922 and 1924, it was largely rebuilt and extended by the society architect Philip Tilden. From the garden front, the house has extensive views over the Weald of Kent, "the most beautiful and charming" Churchill had ever seen, and the determining factor in his decision to buy the house.

In 1946, when financial constraints forced Churchill to again consider selling Chartwell, it was acquired by the National Trust with funds raised by a consortium of Churchill's friends led by Lord Camrose, on condition that the Churchills retain a life-tenancy. After Churchill's death, Lady Churchill surrendered her lease on the house and it was opened to the public by the Trust in 1966. A Grade I listed building, for its historical significance rather than its architectural merit, Chartwell has become among the Trust's most popular properties; some 232,000 people visited the house in 2016, the fiftieth anniversary of its opening.

History

Early history to 1922

The site had been built upon at least as early as the 16th century, when the estate was called Well Street.[2] The origin of the name is the Chart Well, a spring to the north of the current house, Chart being an Old English word for rough ground.[3] Henry VIII was reputed to have stayed in the house during his courtship of Anne Boleyn at nearby Hever Castle.[4] Elements of the Tudor house are still visible, the Historic England listing for Chartwell notes that 16th (or possibly 17th) century brickwork can be seen in some of the external walls.[5] In the 17th and 18th centuries, the house was used as a farmhouse and its ownership was subject to frequent change.[2] In 1848, it was purchased by John Campbell Colquhoun, a former MP; the Campbell Colquhouns were a family of Scottish landowners, lawyers and politicians.[6] The original farmhouse was enlarged and modified during their ownership, including the addition of the stepped gables, a Scottish baronial genuflection to the land of their fathers.[7] By the time of the sale to Churchill, it was, in the words of Oliver Garnett, author of the 2008 guidebook to the house, an example of "Victorian architecture at its least attractive, a ponderous red-brick country mansion of tile-hung gables and poky oriel windows".[2]

Churchill at Chartwell

1922 to 1939

Churchill first saw Chartwell in July 1921, shortly before the house and estate were to be auctioned.[8] He returned the same month with his wife Clementine, who was initially attracted to the property, although her enthusiasm cooled during subsequent visits.[9] In September 1922, when the house had failed to sell at auction, he was offered it for £5,500. He paid £5,000, after his first offer of £4,800, made because "the house will have to be very largely rebuilt, and the presence of dry rot is a very serious adverse factor", was rejected.[10] The seller was Captain Archibald John Campbell Colquhoun, who had inherited the house in June 1922 on the death of his brother.[11] Campbell Colquhoun had been a contemporary of Churchill's at Harrow School in the 1880s. On completion of the sale in September 1922, Churchill wrote to him; "I am very glad indeed to have become the possessor of "Chartwell". I have been searching for two years for a home in the country and the site is the most beautiful and charming I have ever seen".[11] The sale was concluded on 11 November 1922.[12]

The previous 15 months had been personally and professionally calamitous. In June 1921, Churchill's mother had died, followed three months later by his youngest child, Marigold.[12] In late 1922, he fell ill with appendicitis and at the end of the year lost his Scottish parliamentary seat at Dundee.[13]

Philip Tilden, Churchill's architect, began work on the house in 1922 and the Churchills rented a farmhouse near Westerham, Churchill frequently visiting the site to observe progress.[14] The two-year building programme, the ever-rising costs, which escalated from the initial estimate of £7,000 to over £18,000, and a series of construction difficulties, particularly relating to damp, soured relations between architect and client,[15] and by 1924 Churchill and Tilden were barely on speaking terms.[16] Legal arguments, conducted through their respective lawyers, rumbled on until 1927.[17] Clementine's anxieties about the costs, both of building and subsequently living at Chartwell also continued. In September 1923 Churchill wrote to her, "My beloved, I beg you not to worry about money, or to feel insecure. Chartwell is to be our home (and) we must endeavour to live there for many years."[18] Churchill finally moved into the house in April 1924, a letter dated 17 April of that year to Clementine begins, "This is the first letter I have ever written from this place, and it is right that it should be to you".[19]

In February 1926, Churchill's political colleague Sir Samuel Hoare described a visit in a letter to the press baron Lord Beaverbrook; "I have never seen Winston before in the role of landed proprietor, ... the engineering works on which he is engaged consist of making a series of ponds in a valley and Winston appeared to be a great deal more interested in them than in anything else in the world".[20] In January 1928, James Lees-Milne stayed as a guest of Churchill's son Randolph. He described an evening after dinner; "We remained at that round table till after midnight. Mr Churchill spent a blissful two hours demonstrating with decanters and wine glasses how the Battle of Jutland was fought. He got worked up like a schoolboy, making barking noises in imitation of gunfire, and blowing cigar smoke across the battle scene in imitation of gun smoke".[21] On 26 September 1927 Churchill composed the first of his Chartwell Bulletins, which were lengthy letters to Clementine, written to her while she was abroad. In the bulletins, Churchill described in great detail the ongoing works on the house and the gardens, and aspects of his life there. The 26 September letter opens with a report of Churchill's deepening interest in painting; "Sickert arrived on Friday night and we worked very hard at various paintings ... I am really thrilled ... I see my way to paint far better pictures than I ever thought possible before".[22]

Churchill described his life at Chartwell in the later 1930s in the first volume of his history of the Second World War, The Gathering Storm. "I had much to amuse me. I built ... two cottages, ... and walls and made ... a large swimming pool which ... could be heated to supplement our fickle sunshine. Thus I ... dwelt at peace within my habitation".[23] Bill Deakin, one of Churchill's research assistants, recalled his working routine. "He would start the day at eight o'clock in bed, reading. Then he started with his mail. His lunchtime conversation was quite magnificent, ...absolutely free for all. After lunch, if he had guests he would take them round the garden. At seven he would bathe and change for dinner. At midnight, when the guests left, then he would start work ... to three or four in the morning. The secret was his phenomenal power to concentrate."[24]

In the opinion of Robin Fedden, a diplomat, and later Deputy General Secretary of the National Trust and author of the Trust's first guidebook for Chartwell, the house became "the most important country house in Europe".[25] A stream of friends, colleagues, disgruntled civil servants and concerned military officers came to the house to provide information to support Churchill's struggle against appeasement. At Chartwell, he developed what Fedden calls, his own "little Foreign Office ... the hub of resistance".[26] The Chartwell visitors' book, meticulously maintained from 1922, records some 780 house guests, not all of them friends, but all grist to Churchill's mill.[27] An example of the latter was Sir Maurice Hankey, Clerk of the Privy Council, who was Churchill's guest for dinner in April 1936. Hankey subsequently wrote, "I do not usually make a note of private conversations but some points arose which gave an indication of the line which Mr Churchill is likely to take in forthcoming debates (on munitions and supply) in Parliament".[28] A week later, Reginald Leeper, a senior Foreign Office official and confident of Robert Vansittart, visited Churchill to convey their views on the need to use the League of Nations to counter German aggression. Vansittart wrote, "there is no time to lose. There is indeed a great danger that we shall be too late".[29]

Churchill also recorded visits to Chartwell by two more of his most important suppliers of confidential governmental information, Desmond Morton and Ralph Wigram, information which he used to "form and fortify my opinion about the Hitler Movement".[30] Chartwell was also the scene of more direct attempts to prepare Britain for the coming conflict; in October 1939, when reappointed First Lord of the Admiralty on the outbreak of war, Churchill suggested an improvement for anti-aircraft shells; "Such shells could be filled with zinc ethyl which catches fire spontaneously ... A fraction of an ounce was demonstrated at Chartwell last summer".[31]

In 1938, Churchill, beset by financial concerns, again considered selling Chartwell,[32] at which time the house was advertised as containing five reception rooms, nineteen bed and dressing rooms, eight bathrooms, set in eighty acres with three cottages on the estate and a heated and floodlit swimming pool. He withdrew the sale after the industrialist Henry Strakosch agreed to take over his share portfolio, which had been hit heavily from losses on Wall Street, for three years and pay off significant associated debts.[33]

1939 to 1965

Chartwell was mostly unused during the Second World War.[34] Its exposed position in a county so near to German occupied France, meant that it was vulnerable to a German airstrike or commando raid. As a precaution the lakes were covered with brushwood to make the house less identifiable from the air.[26] A rare visit to Chartwell occurred in July 1940, when Churchill inspected aircraft batteries in Kent. His pre-war writing assistant Eric Seal recorded the visit; "In the evening the PM, Mrs C and I went off to Chartwell. One of the features of the place is a whole series of ponds, which are stocked with immense goldfish. The PM loves feeding them".[35] The Churchills instead spent their weekends at Ditchley House, in Oxfordshire, until security improvements were completed at the Prime Minister's official country residence, Chequers, in Buckinghamshire.[36] At dinner at Chequers, in December 1940, John Colville, Churchill's assistant private secretary recorded his master's post-war plans, "He would retire to Chartwell and write a book on the war, which he had already mapped out in his mind chapter by chapter".[37]

Chartwell remained a haven in times of acute stress[38] – Churchill had spent the night there just before the fall of France in 1940.[39] Summoned back to London by an urgent plea from Lord Gort for permission to retreat to Dunkirk, Churchill broadcast the first of his wartime speeches to the nation; "Arm yourselves, and be ye men of valour...for it is better for us to perish in battle than to look upon the outrage of our nation..."[40] He returned again on 20 June 1941, after the failure of Operation Battleaxe to relieve Tobruk, and determined to sack the Middle East commander, General Wavell. John Colville recorded Churchill's deliberations in his diary; "spent the afternoon at Chartwell. After a long sleep the P.M. in a purple dressing gown and grey felt hat took me to see his goldfish. He was ruminating deeply about the fate of Tobruk and contemplating means of resuming the offensive".[41] Churchill continued to pay occasional, short, visits to the house; on one such, on 24 June 1944, just after the Normandy landings, his secretary recorded that the house was "shut up and rather desolate".[42]

After VE Day, the Churchills first returned to Chartwell on 18 May 1945, to be greeted by what the horticulturalist and garden historian Stefan Buczacki describes as, "the biggest crowd Westerham had ever seen".[43] But military victory was rapidly followed by political defeat as Churchill lost the June 1945 general election. He almost immediately went abroad, while Clementine went back to Chartwell to begin the long process of opening up the house for his return[44] – "it will be lovely when the lake camouflage is gone".[45] Later that year, Churchill again gave thought to selling Chartwell, concerned by the expense of running the estate. A group of friends, organised by Lord Camrose, raised the sum of £55,000 which was passed to the National Trust allowing it to buy the house from Churchill for the sum of £43,800. The excess provided an endowment.[46] The sale was completed on 29 November.[47] For payment of a rent of £350 per annum, plus rates,[47] the Churchills committed to a 50-year lease, allowing them to live at Chartwell until their deaths, at which point the property would revert to the National Trust.[48] Churchill recorded his gratitude in a letter to Camrose in December 1945, "I feel how inadequate my thanks have been, my dear Bill, who (...) never wavered in your friendship during all these long and tumultuous years".[49]

In the summer of 1953, Chartwell became Churchill's refuge once more when, again in office as Prime Minister, he suffered a massive stroke. At the end of a dinner held on 23 June at 10 Downing Street, for the Italian Prime Minister Alcide De Gasperi, Churchill collapsed and was barely able either to stand or to speak.[50] On the 25th, he was driven to Chartwell, where his condition deteriorated further. Churchill's doctor Lord Moran stated that, "he did not think the Prime Minister could possibly live over the weekend".[51] That evening Colville summoned Churchill's closest friends in the press, Lord Beaverbrook, Lord Camrose and Brendan Bracken who, walking the lawns at Chartwell, agreed to try to ensure a press blackout to prevent any reporting of Churchill's condition.[52] Colville described the outcome, "They achieved the all but incredible success of gagging Fleet Street, something they would have done for nobody but Churchill. Not a word of the Prime Minister's stroke was published until he casually mentioned it in the House of Commons a year later".[53] Secluded and protected at Chartwell, Churchill made a remarkable recovery and thoughts of his retirement quickly receded.[54] During his recuperation, Churchill took the opportunity to complete work on Triumph and Tragedy, the sixth and final volume of his war memoirs, which he had been forced to set aside when he returned to Downing Street in 1951.[55]

Churchill's final departure from political office came some sixteen months later when, on 5 April 1955, he chaired his last cabinet, almost fifty years since he had first sat in the Cabinet Room as President of the Board of Trade in 1908.[56] The following day he held a tea party for staff at Downing Street before driving to Chartwell. On being asked by a journalist on arrival how it felt no longer to be Prime Minister, Churchill replied, "It's always nice to be home".[57] For the next ten years, Churchill spent much time at Chartwell, although both he and Lady Churchill also travelled extensively. His days there were spent writing, painting, playing bezique or sitting "by the fish pond, feeding the golden orfe and meditating".[58] Of his last years at the house, Churchill's daughter, Mary Soames, recalled, "in the two summers that were left to him he would lie in his 'wheelbarrow' chair contemplating the view of the valley he had loved for so long".[59] On 13 October 1964, Churchill's last dinner guests at Chartwell were his former principal private secretary Sir Leslie Rowan and his wife. Lady Rowan later recalled, "It was sad to see such a great man become so frail".[60] The following week, increasingly incapacitated, Churchill left the house for the last time. His official biographer Martin Gilbert records Churchill was, "never to see his beloved Chartwell again".[60] After his death in January 1965, Lady Churchill immediately relinquished her lease and presented Chartwell to the National Trust.[48] It was opened to the public in 1966, one year after Churchill's death.[61]

National Trust: 1966 to 2017

The house has been restored and preserved as it looked in the 1920-30s; at the time of the Trust's purchase, Churchill committed to leave it, "garnished and furnished so as to be of interest to the public".[62] Rooms are decorated with memorabilia and gifts, the original furniture and books, as well as honours and medals that Churchill received.[5] Lady Churchill's long-time secretary, Grace Hamblin, was appointed the first administrator of the house.[58] Earlier in her career, Miss Hamblin had undertaken the destruction of the portrait of Churchill painted by Graham Sutherland. The picture, a gift from both Houses of Parliament on Churchill's 80th birthday in 1954, was loathed by both Churchill and Lady Churchill[63] and had been stored in the cellars at Chartwell before being burnt in secret.[64]

The opening of the house required the construction of facilities for visitors and a restaurant was designed by Philip Jebb, and built to the north of the house, along with a shop and ticket office.[65] Alterations have also been made to the gardens, for ease of access and of maintenance. In 1987, the Great Storm caused considerable damage, with some twenty-three trees being blown down in the gardens.[66] Greater loss occurred in the woodlands surrounding the house, which lost over 70% of its trees.[67]

Chartwell has become among the National Trust's most popular properties; in 2016 some 232,000 visitors came to the house.[68] In that year, the fiftieth anniversary of the house's opening, the Trust launched the Churchill's Chartwell Appeal, to raise £7.1M for the purchase of hundreds of personal items held at Chartwell on loan from the Churchill family.[69] The items available to the Trust include Churchill's Nobel Prize in Literature awarded to him in 1953.[70] The citation for the award reads, "for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values".[71] The medal is displayed in the museum room on the first floor of Chartwell, at the opposite end of the house to the study, the room where, in the words used by John F. Kennedy when awarding him honorary citizenship of the United States, Churchill "mobilized the English language and sent it into battle".[72]

Architecture and description

The highest point of the estate is approximately 650 feet above sea level, and the house commands views across the Weald of Kent. The view from the house was of crucial importance to Churchill; years later, he remarked, "I bought Chartwell for that view."[1]

Exterior

Churchill employed the architect Philip Tilden, who worked from 1922–24 to modernise and extend the house.[73] Tilden was a "Society" architect who had previously worked for Churchill's friend Philip Sassoon at his Kent home, Port Lympne,[74] and had designed Lloyd George's house, Bron-y-de, at Churt.[15] The architectural style is vernacular. The house is constructed of red brick, of two storeys, with a basement and extensive attics.[5] The 18th century doorcase in the centre of the entrance front was purchased from a London antiques dealer.[75] The architectural historian John Newman considered it, "large and splendid and out of place".[76] The garden wall on the Mapleton Road is modelled on that at Quebec House, the home of General Wolfe in nearby Westerham.[77]

On the garden front, Tilden threw up a large, three storey extension with stepped gables, called by Churchill "my promontory", which contains three of the house's most important rooms, the dining room, in the lower-storey basement, and the drawing room and Lady Churchill's bedroom above.[78]

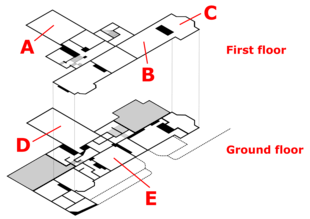

Interior

The interior has been remodelled since the National Trust took over the property in 1966, to accommodate visitors and to enable the display of a large number of Churchillian artefacts. In particular, a number of guest bedrooms have been amalgamated, to allow the construction of the Museum room and the Uniform room.[79] Nevertheless, the majority of the principal rooms have been reconstructed and furnished as they were in the 1920s–30s[62] and are open to the public, with the current exception of Churchill's own bedroom.[80]

Entrance hall and inner hall

Designed by Tilden, replacing a wood-panelled earlier hall, the halls lead onto the library, the drawing room and Lady Churchill's sitting room.[81]

Dining room

—Churchill's note on the requirements of a dining chair.[82]

The bottom section of Tilden's "promontory" extension, the dining room contains the original suite of table and dining chairs designed by Heal's to Churchill's exacting requirements – (see box).[82] An early study for a planned picture by William Nicholson entitled Breakfast at Chartwell hangs in the room. Nicholson, a frequent visitor to Chartwell who gave Churchill painting lessons, drew the study for a finished picture which was intended as a present for the Churchills' Silver Wedding anniversary in 1933 but, disliking the final version, Nicholson destroyed it.[83] The picture depicts the Churchills breakfasting together, which in fact they rarely did, and Churchill's marmalade cat, Tango.[84] The tradition of keeping a marmalade cat at Chartwell, which Churchill began and followed throughout his ownership, is maintained by the National Trust in accordance with Churchill's wishes.[85] In a letter to Randolph written in May 1942, Churchill wrote of a brief visit to Chartwell the previous week, "the goose and the black swan have both fallen victim to the fox. The Yellow Cat however made me sensible of his continuing friendship, although I had not been there for eight months".[86]

Above the dining room is the drawing room and, above that, Lady Churchill's bedroom,[87] described by Churchill as "a magnificent aerial bower".[88]

Study

Churchill's study, on the first floor, was his "workshop for over 40 years"[89] and "the heart of Chartwell".[90] In the 1920s, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, he planned his budgets in the room; in the 1930s, in isolation, he composed his speeches that warned against the rise of Hitler and dictated the books and articles that paid the bills; in 1945, defeated, he retreated here to write his histories; and here, in final retirement, he passed much of his old age.[90] Throughout the 1930s, the study was his base for the writing of many of his most successful books. His biography of his ancestor Marlborough and his The World Crisis were written there, and A History of the English-Speaking Peoples was begun and concluded there, although interrupted by the Second World War.[89] He also wrote many of his pre-war speeches in the study, although the house was less used during the war itself. Tilden exposed the early roof beams by removing the late-Victorian ceiling and inserted a Tudor doorcase.[91] From the beams hang three banners, Churchill's standards as Knight of the Garter and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and the Union Flag raised over Rome on the night of 5 June 1944, the first British flag to fly over a liberated capital.[92] The latter was a gift from Lord Alexander of Tunis.[93] The study also contains portraits of Churchill's parents, Lord Randolph Churchill and Lady Randolph Churchill, the latter by John Singer Sargent.[94] The floor is covered with a Khorassan carpet, a 69th birthday gift to Churchill from the Shah of Iran at the Teheran Conference in 1943.[95]

Beyond the study are Churchill's bedroom and his ensuite bathroom, with sunken bath. At the time of the house's opening to the public in 1966, these rooms were not made accessible, at the request of Churchill's family but, shortly before her death in 2014, Churchill's daughter Mary gave permission for their opening, and the Trust plans to make them accessible by 2020.[80]

Architectural appreciation

Neither the original Victorian house with its extensions, nor Tilden's reconstruction, created a building that has been highly regarded by critics. John Newman noted that the massing of the house on the garden terraces, taking advantage of the Wealden views, was "the grouping that mattered". He dismissed the other side of the house as a, "long, indecisive entrance front close to the road" [96] and the overall composition as of "dull red brick and an odd undecided style".[76] The architectural writer and Chairman of the National Trust Simon Jenkins considered the house, "undistinguished".[97] The National Trust's guidebook describes the original building as "Victorian architecture at its least attractive".[2] The house is Grade I listed but its brief, Historic England listing makes clear that this is "for historical reasons"[5] rather than for its architectural quality. The gardens are Grade II* listed.[98]

Gardens and estate

The gardens surrounding the house comprise 8 hectares (20 acres), with a further 23 hectares (57 acres) of parkland.[98] They are predominantly the creation of Churchill and Lady Churchill, with significant later input from Lanning Roper, Gardens Adviser to the National Trust.[98] The Victorian garden had been planted with conifers and rhododendrons which were typical of the period.[67] The Churchills removed much of this planting, while retaining the woodlands beyond. Within the garden proper, they created almost all of the landscape, architectural and water features seen today.[67] The garden front of the house opens onto a terraced lawn, originally separated from the garden beyond by a ha-ha and subsequently by a Kentish ragstone wall constructed in the 1950s.[98] To the north lies the Rose garden, laid out by Lady Churchill and her cousin, Venetia Stanley.[99] The nearby Marlborough Pavilion was built by Tilden and decorated with frescos by Churchill's nephew, John Spencer Churchill in 1949.[100] Beyond the Rose Garden is the Water Garden, constructed by the Churchills and including the Golden Orfe pond where Churchill fed his fish, and the swimming pool constructed in the 1930s. Churchill sought advice from his friend and scientific guru Professor Lindemann on the optimal methods for heating and cleaning the pool.[101]

To the south, is the Croquet lawn, previously a tennis court[102] – Lady Churchill was an accomplished and competitive player of both,[103] although Churchill was not.[102] Beyond the lawn are a number of structures grouped around the Victorian kitchen garden, many of which Churchill was involved in building.[104] He had developed an interest in bricklaying when he bought Chartwell and throughout the 1920s and 1930s constructed walls, a summerhouse and a number of houses on the estate.[102] In 1928 he joined the Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers, a move which caused some controversy.[105] Near the kitchen garden are the Golden Rose walk, a Golden Wedding anniversary present to the Churchills from their children in 1958,[106] and Churchill's painting studio, constructed in the 1930s, which now houses a large collection of his artistic works.[107]

South of the terrace lawn are the Upper and Lower lakes, scene of Churchill's most ambitious landscaping schemes.[108] The Lower lake had existed during the Colquhouns' ownership, but the island within it, and the Upper lake, were Churchill's own creations. On 1 January 1935, while Lady Churchill was on a cruise off Sumatra, Churchill described the beginnings of his endeavours in one of his Chartwell Bulletins; "I have arranged to have one of those great mechanical diggers. In one week he can do more than 40 men can do. There is no difficulty about bringing him in as he is a caterpillar and can walk over the most sloppy fields".[109] Excavation work proved more challenging than Churchill had anticipated, two weeks later he wrote again, "The mechanical digger has arrived. He moves about on his caterpillars only with the greatest difficulty on this wet ground".[110]

On the lakes lived Churchill's large collection of wildfowl, including the black swans, a gift from the Australian Government,[111] which restocked the lakes with them in 1975.[112]

In 1946–47, Churchill extended his land-holdings around Chartwell, purchasing Chartwell Farm and Parkside Farm, and subsequently Bardogs Farm and a market garden. By 1948, he was farming approximately 500 acres.[113] The farms were managed by Mary Soames's husband, Christopher[114] and Churchill kept cattle and pigs and also grew crops and market vegetables. The farms did not prove profitable, however, and by 1952, Churchill's operating losses on them exceeded £10,000 a year.[115] By the end of the decade, the farms and the livestock had been sold.[116] A somewhat more lucrative venture was the owning, and later breeding, of racehorses. In 1949, Churchill had purchased Colonist II, which won its first race, the Upavon Stakes, at Salisbury that year, and subsequently netted Churchill some £13,000 in winnings.[117] In 1955 Churchill bought the Newchapel Stud and by 1961 his total prize money from racing exceeded £70,000.[118] In the 1950s, he reflected on his racing career; "Perhaps Providence had given him Colonist as a comfort in his old age and to console him for disappointments".[119]

See also

- 28 Hyde Park Gate (Churchill's London home)

- Blenheim Palace (Churchill's birthplace)

- Churchill Archives Centre

- Churchill War Rooms (London)

References

- 1 2 Hall, Douglas J. (14 February 2009). "Churchill, Chartwell, and the Garden of England". The International Churchill Society. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Garnett 2008, p. 13.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 105.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 Historic England. "Chartwell (1272626)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 110.

- ↑ Banergee, Jacqueline (21 August 2016). "Styles in Domestic Architecture". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 100.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 101.

- ↑ Gilbert 1975, p. 793.

- 1 2 Gilbert 1977, p. 2027.

- 1 2 Garnett 2008, p. 11.

- ↑ Soames 1998, pp. 263–265.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 269.

- 1 2 Bettley 1987, p. 15.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 152.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 273.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 281.

- ↑ Gilbert 1976, p. 145.

- ↑ Gilbert 1976, p. 265.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 309.

- ↑ Churchill 1948, p. 62.

- ↑ Gilbert 1976, p. 730.

- ↑ Fedden 1974, p. 3.

- 1 2 Fedden 1974, p. 10.

- ↑ Roberts 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ Gilbert 1976, p. 723.

- ↑ Gilbert 1976, p. 726.

- ↑ Churchill 1948, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Gilbert 1993, p. 228.

- ↑ Churchill 1997, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 28.

- ↑ Reynolds 2004, p. 3.

- ↑ Gilbert 1983, p. 654.

- ↑ Gilbert 1983, p. 900.

- ↑ Gilbert 1983, p. 943.

- ↑ Gilbert 1983, p. 1113.

- ↑ Hastings 2010, p. 19.

- ↑ Hastings 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Colville 1985, pp. 402–403.

- ↑ Gilbert 1986, p. 837.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 226.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 533.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 538.

- ↑ Lough 2016, p. 321.

- 1 2 Gilbert 1988, p. 304.

- 1 2 Garnett 2008, p. 6.

- ↑ Reynolds 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Gilbert 1988, pp. 846–847.

- ↑ Gilbert 1988, p. 849.

- ↑ Gilbert 1988, p. 852.

- ↑ Colville 1985, p. 669.

- ↑ Colville 1985, p. 673.

- ↑ Reynolds 2004, p. 441.

- ↑ Gilbert 1988, p. 1112.

- ↑ Gilbert 1988, p. 1125.

- 1 2 Garnett 2008, p. 35.

- ↑ Gilbert 1988, p. 1345.

- 1 2 Gilbert 1988, p. 1357.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 278.

- 1 2 Buczacki 2007, p. 279.

- ↑ Clubbe 2016, p. 6.

- ↑ Furness, Hannah (10 July 2015). "Secret of Winston Churchill's unpopular Sutherland portrait revealed". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 283.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 285.

- 1 2 3 Garnett 2008, p. 70.

- ↑ "Visits made in 2016 to visitor attractions in membership with ALVA". Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Press Association (4 September 2016). "National Trust hopes to buy Churchill's country house heirlooms". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2017 – via The Guardian.

- ↑ "Churchill's highest literary honour". The National Trust. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1953". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Shapiro, Gary (12 June 2012). "How Churchill Mobilized the English Language". The New York Sun. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Bettley 1987, p. 16.

- ↑ Aslet 2005, p. 61.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 17.

- 1 2 Newman 2002, p. 199.

- ↑ Fedden 1974, p. 21.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 60.

- 1 2 "New room openings coming soon at Chartwell". The National Trust. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, pp. 46–47.

- 1 2 Soames 1998, p. 259.

- ↑ "Study for Breakfast at Chartwell II, Sir Winston Churchill (1874–1965) and Clementine Ogilvy Hozier, Lady Churchill (1885–1977) in the Dining Room at Chartwell with their Cat 1102453". National Trust Collections. The National Trust. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Reidy, Chrissie (11 March 2014). "Chartwell kitten Jock VI upholds Winston Churchill's wish". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Gilbert 1986, p. 99.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 47.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 55.

- 1 2 Garnett 2008, p. 63.

- 1 2 Fedden 1974, p. 40.

- ↑ Fedden 1974, p. 41.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 65.

- ↑ Fedden 1974, p. 44.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 64.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 66.

- ↑ Newman 2012, p. 149.

- ↑ Jenkins 2003, p. 352.

- 1 2 3 4 Historic England. "Chartwell (1000263)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Fedden 1974, p. 50.

- ↑ Garnett 2008, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Garnett 2008, p. 77.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 573.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 169.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Fedden 1974, p. 52.

- ↑ Fedden 1974, p. 59.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 191.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 369.

- ↑ Soames 1998, p. 373.

- ↑ Churchill 1997, p. 277.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 198.

- ↑ Soames 1998, pp. 541–542.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 236.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 240.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 244.

- ↑ Glueckstein, Fred (December 2004). "Winston Churchill and Colonist II". The International Churchill Society. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Buczacki 2007, p. 248.

- ↑ Gilbert 1988, p. 563.

Sources

- Aslet, Clive (2005). Landmarks of Britain. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-73510-7.

- Bettley, James (1987). Lush and Luxurious: The life and work of Philip Tilden 1887–1956. London: Royal Institute of British Architects. OCLC 466189961.

- Buczacki, Stefan (2007). Churchill & Chartwell – The Untold Story of Churchill's Houses and Gardens. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-2535-0.

- Churchill, Winston (1948). The Gathering Storm. The Second World War. I. London: Cassell & Co. OCLC 162830625.

- Churchill, Winston; Churchill, Clementine (1998). Soames, Mary, ed. Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill. London: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-40691-6.

- Churchill, Winston S. (1997). His Father's Son: The Life of Randolph Churchill. London: Orion Books. ISBN 9-78185-799969-3.

- Clubbe, John (2016). Byron, Sully, and the Power of Portraiture. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-67557-5.

- Colville, Jock (1985). The Fringes of Power – 10 Downing Street Diaries 1939–1955. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9-78034-038296-7.

- Fedden, Robin (1974). Churchill And Chartwell. Oxford: Pergamon Press. OCLC 228659396.

- Garnett, Oliver (2008). Chartwell. Swindon: National Trust Enterprises. OCLC 828689009.

- Gilbert, Martin (1975). Winston S. Churchill 1917–1922. Authorised biography of Winston S. Churchill. IV. London: Heinemann. OCLC 782000964.

- ——— (1977). Companion Volume, April 1921 – November 1922. Authorised biography of Winston S. Churchill. IV Part 3. London: Heinemann. OCLC 4354393.

- ——— (1976). Winston S. Churchill 1922–1939. Authorised biography of Winston S. Churchill. V. London: Heinemann. OCLC 715481469.

- ——— (1983). Finest Hour: Winston S. Churchill 1939–1941. Authorised biography of Winston S. Churchill. VI. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9-780434-29187-8.

- ——— (1986). Road to Victory: Winston S. Churchill 1941–1945. Authorised biography of Winston S. Churchill. VII. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9-78043-413017-7.

- ——— (1988). Never Despair: Winston S. Churchill 1945–1965. Authorised biography of Winston S. Churchill. VIII. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9-78077-372187-6.

- ——— (1993). The Churchill War Papers, At the Admiralty, September 1939 to May 1940. Authorised biography of Winston S. Churchill. I. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03522-0.

- Hastings, Max (2010). Finest Years: Churchill as Warlord 1940–45. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 9-780007-26368-4.

- Jenkins, Simon (2003). England's Thousand Best Houses. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-713-99596-3.

- Lough, David (2016). No More Champagne: Churchill and His Money. London: Head of Zeus Ltd. ISBN 978-178408-1829.

- Newman, John (2002). West Kent and The Weald. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09614-3.

- ——— (2012). Kent: West and The Weald. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18509-6.

- Reynolds, David (2004). In Command of History - Churchill Fighting and Writing the Second World War. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-713-99819-9.

- Roberts, Andrew (2008). Masters and Commanders. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9-78006-122857-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chartwell. |