Central Subway

|

4th Street Portal under construction in February 2016 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other name(s) | Third Street Light Rail Project Phase 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | San Francisco, California | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°46′48″N 122°23′55″W / 37.779921°N 122.398540°WCoordinates: 37°46′48″N 122°23′55″W / 37.779921°N 122.398540°W (southern portal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Under construction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | Muni Metro | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crosses | Market Street Subway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Start | 4th Street Portal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| End | Chinatown Station | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No. of stations | 3 (plus 1 surface as part of extension project) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Work begun | 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constructed | Tutor Perini[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opens |

December 26, 2018 — December 10, 2019[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | San Francisco Municipal Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Underground subway tunnel for predominantly light rail line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 1.7 mi (2.74 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No. of tracks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrified | Overhead lines, 600 V DC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

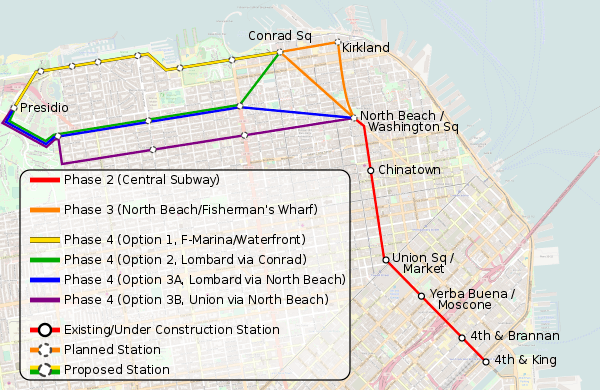

The Central Subway is an extension of the Muni Metro light rail system under construction in San Francisco, California, from the Caltrain commuter rail depot at 4th and King streets to Chinatown, with stops in South of Market (SoMa) and Union Square.

The subway is the second phase of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency's Third Street Light Rail Project. The first phase opened to the public as the T Third Line in 2007. Ground was broken for the Central Subway on February 9, 2010.[3] Tunnel boring for the Central Subway was completed at Columbus and Powell Street in the North Beach neighborhood of San Francisco on June 11, 2014.[4] This subway extension of the T Third Line, originally set to open in late 2018[5], is projected to open to the public in 2021.[6] With the addition of the Central Subway, the T Third Line is projected to become the most heavily ridden line in the Muni Metro system by 2030.[7]

The extension will serve major employment and population centers in San Francisco that are underserved by rapid transit.[8] SoMa is home to the headquarters of many of San Francisco’s major software and technology companies, and substantial residential growth is projected there.[9] Union Square, located in the city's downtown, is a primary commercial and economic district.[10] Chinatown is the most densely populated neighborhood in the city.[11] The Central Subway will connect these areas to communities in eastern San Francisco, including Mission Bay, Dogpatch, Bayview-Hunters Point and Visitacion Valley.

The budget to complete the Central Subway is $1.578 billion. The project is funded primarily through the Federal Transit Administration’s New Starts program. In October 2012, the FTA approved a Full Funding Grant Agreement, the federal commitment of funding through New Starts, for the Central Subway for a total amount of $942.2 million.[12] The Central Subway is also funded by the State of California, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the San Francisco County Transportation Authority and the City and County of San Francisco.[13]

Alignment

In February 2008, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency board of directors voted to select the alignment for the subway.[14][15] In the approved alignment, trains travel north along 4th Street and Stockton Street, stopping at one above-ground station and three subway stations on their 1.7-mile route.

Currently northbound T Third Line trains turn right from 4th Street onto King Street and travel along the Embarcadero to the Market Street Tunnel. When the Central Subway is complete, trains will instead cross King Street and continue north on 4th Street.

The first stop will be at an above-ground station at 4th and Brannan streets, the 4th and Brannan Station. Heading north, trains will enter the subway through a portal on 4th Street between Bryant and Harrison streets, under Interstate 80. The route will then continue under 4th Street through South of Market, stopping at an underground station, the Yerba Buena/Moscone Station, at 4th and Clementina streets, near the Moscone Center. At Market Street, the subway will dip below the Market Street Subway. Another underground station serving Market Street and Union Square will be located underneath Stockton Street. This combined Union Square/Market Street Station will have entrances at the Market, Ellis and Stockton intersection and within Union Square Plaza at Stockton and Geary streets. A pedestrian passage will connect the Union Square/Market Street Station to the Muni Metro and BART Powell Street Station. The subway will then continue under Stockton Street to Chinatown Station, a station to be located in Chinatown at Stockton and Washington streets.[16][17] Two of the three underground stations are being constructed using cut-and-cover methods while Chinatown Station is being constructed with the sequential excavation method.[18][19]

The subway tunnels, one for northbound trains and one for southbound trains, will continue north past Chinatown Station, along Stockton Street (becoming the second tunnel under Stockton Street) and terminate near Columbus Avenue. In the future, the northern end of the T Third Line may be extended to terminate in North Beach or to Fisherman's Wharf and the Aquatic Park to connect with F Market & Wharves. Fourteen alternative routes were proposed in a 2014 study to extend the line, and daily ridership was projected to increase by 40,000 if the extension was completed.[20] San Francisco Chronicle architecture critic John King wrote there was "a compelling power to the idea of an extension that, if nothing else, would make the Central Subway seem less like a boondoggle and more of a factor in the shaping of tomorrow’s city. The empty lot of the Pagoda was a starting point for dreams. Let’s see if it can become a starting point of something real as well."[21]

Cost

In 2000, the estimated cost of the Central Subway project was $530 million.[22] By 2001, the cost had risen to $647 million and completion was projected for 2009.[23] When construction began in 2012, the cost had reached $1.6 billion.[24] When the main contract for Central Subway construction was awarded in May 2013 to the lowest bidder, Tutor Perini,[25] the $840 million contract was up to $120 million over the budgeted amount, which took up nearly two-thirds of the entire project's contingency.[26]

Due to the capital cost ($1.578 billion for the 1.7 mile light rail line), the Central Subway project has come under criticism from transit activists for what they consider to be poor cost-effectiveness.[27] In particular, they note that Muni's own estimates show that the project would increase Muni ridership by less than 1% and yet by 2030 would adding $15.2 million a year to Muni's annual operating deficit.[28]

This position is countered by the fact that, unlike new rail construction projections in low-density areas in America, the Central Subway would augment access to the densest portions of Chinatown and the northern Financial District. Current transit access to these areas is provided entirely on the surface through small blocks that feature intense pedestrian activity and narrow streets with multi-modal street congestion. Other, lower-cost rapid transit options were explored, such as Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), but were rejected in part because these conditions do not support the basic features of efficient BRT operations.

Compounding these conditions is the fact that many Chinatown residents are transit-dependent and do not own cars, helping rationalize funding for a subway. The high-ridership Muni bus lines serving Chinatown (e.g., the 1 California and the 30 Stockton) are typically extremely overcrowded, making service for customers more excruciating as excessive boarding activity slows travel speeds or exacerbates overcrowding until no more riders can be accepted and buses are forced to pass customers at successive stops, effectively denying them service.[24]

.jpg)

In October 2012, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) announced it will provide $942.2 million for the project under its New Starts program[29] after indicating it would approve the grant in January.[30] This award included the recognition that better, more comfortable service for an already intensively-used transit corridor, particularly for low-income residents as in Chinatown, justifies the investment even if it does not attract a high percentage of "new" riders the way a new rapid transit investment might somewhere that is not already served by extremely slow, uncomfortable high-ridership local service.[12]

Construction

A study released in 2000 called for the Central Subway as part of a larger plan to alleviate projected traffic gridlock which also included a light rail line along Geary.[31] Voters approved the Central Subway in 2003, and the alignment was selected in 2008.[15] Physical work began on the Central Subway in June 2012. The first phases of work included preparation of the tunnel boring machine launch site and headwalls for the Yerba Buena/Moscone Station.[32] At the time, the FTA grant had not been secured, and opponents were threatening lawsuits over potential disruption to traffic and businesses.[33]

Tunnel boring

.jpg)

The two tunnel boring machines (TBMs) are named "Big Alma" and "Mom Chung" (for "Big" Alma Spreckels and Dr. Margaret "Mom" Chung, respectively).[34] Preparations for tunnel boring began on June 12, 2012, with the start of excavation for the TBM launch box on Fourth Street between Bryant and Harrison.[32] "Mom Chung" was delivered to San Francisco in April and May 2013,[35][36] and in late July 2013, "Mom Chung" began digging the tunnel for southbound T Third Line trains.[37] "Big Alma" began digging north in November 2013 at a slightly faster rate, 54 ft/d (0.19 m/ks), compared to the 44 ft/d (0.16 m/ks) average of "Mom Chung".[38]

The initial plan was to remove the two TBMs near Washington Square in North Beach in 2014 once boring was complete.[39] On July 31, 2012, a lawsuit was filed in Superior Court by Marc Bruno and Save North Beach, a 501(c)(4) organization of North Beach merchants and residents who believed that the removal of the equipment on Columbus Avenue would cause permanent harm to the neighborhood near Washington Square.[40] The petitioners pointed out in their suit that they are in favor of the City's "Transit First" policy and that they would favor the removal of the equipment if a subway stop was planned, approved and financed for their neighborhood.

Muni General Manager Ed Reiskin announced a plan in December 2012 to extend the tunnel to Columbus and Powell, using the site of the long-closed Pagoda Palace theater to extract the TBMs, with a potential option to purchase the Pagoda as the site of a future North Beach station.[41] In 2013, MTA reached a lease agreement with the owners of the Pagoda to tear down the old building and use its site for TBM removal. This will reduce impact of construction on the public space.[42]

On June 11, 2014, "Big Alma" broke through to the North Beach extraction shaft, joining "Mom Chung", which had arrived on June 2. The arrival of the TBMs marked the completion the boring operation phase.[4] The two TBMs were to be disassembled and removed, and the extraction shaft filled in by the end of 2014.[43] The twin tunnels were fully complete by May 2015, when Mayor Ed Lee toured the project underground. Each completed tunnel is 8,500 feet (2,600 m) long and 20 feet (6.1 m) in diameter, supported by 1,750 concrete rings placed during the boring operation.[44]

Schedule

Just before construction began in 2012, the start of revenue service on the Central Subway extension was scheduled for December 2018.[24] When the main contract was awarded to Tutor Perini in May 2013, schedule float (the amount of time set aside for delays) was reduced from 14.8 months to 5.2 months.[26] In 2014, the San Francisco Controller's Office audited the project and predicted it would be completed on schedule in December 2018 and slightly under budget.[45] Tunnel boring completed in June 2014, a month ahead of schedule and under budget.[44]

Over Labor Day weekend 2015, between September 5-8, the track at the intersection of 4th Street and King Street was extended, which temporarily shortened the services of T Third Street between 4th and King Station (referred to as 4th and Berry in the notice) and Sunnydale Station; the K Ingleside route also ended at Embarcadero Station and did not splice with the T Third Street route.[46][47] A similar shutdown was imposed in early November 2015. During the November shutdown, bus service was provided in lieu of the T-Third trains between Embarcadero and Sunnydale; E-Embarcadero service was suspended for two weekends; K-Ingleside again terminated at Embarcadero; and streets were closed in the vicinity of 4th and King.[48]

| Date | Incurred Costs | Funding[lower-alpha 1] | Completion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $(M)[lower-alpha 2] | %[lower-alpha 3] | $(M)[lower-alpha 2] | %[lower-alpha 3] | Date[lower-alpha 4] | %[lower-alpha 5] | ||

| 2015 | Jan[49] | 747.65 | 47.37 | 1,029.79 | 65 | Dec 2018 | 46.5 |

| Jul[50] | 818.77 | 51.88 | Feb 2019 | —[lower-alpha 6] | |||

| 2016 | Jan[51] | 893.70 | 56.62 | 1,179.79 | 75 | May 2019 | 59 |

| Jul[52] | 963.51 | 61.05 | Jul 2019 | 61 | |||

| 2017 | Jan[53] | 1,025.99 | 65.01 | 1,329.79 | 84 | Oct 2019 | 64.8 |

| Jul[54] | 1,094.84 | 69.31 | Dec 2019 | 70.6 | |||

| 2018 | Jan[55] | 1,178.42 | 74.66 | 1,479.79 | 94 | Nov 2019 | 74.6 |

| Notes | |||||||

A Project Management Oversight Committee report released in mid-2017 reported ten months of delays in construction, pushing back the date of service as late as December 10, 2019. The $76 million contingency fund may be used to expedite completion.[2] The delays were attributed to work on the Chinatown station.[56] In December 2017, Tutor Perini (TPC) circulated a report predicting a fifteen-month delay past December 2019 due to circumstances beyond their control, including hard rock and required utility relocations. TPC is liable for penalties of up to $50,000 per day for late completion beyond December 2019.[6]

Also in December 2017, the Central Subway Program Director, John Funghi, announced he will leave the project for Caltrain, where he will head the Peninsula Corridor Electrification Project starting in February 2018.[57] In April 2018, SFMTA announced that excavation was complete for Chinatown station, which will be the last station to be completed for Central Subway in mid-2019. The other underground stations, Yerba Buena/Moscone and Union Square, are scheduled to be completed by the end of 2018 ahead of the scheduled December 2019 start of revenue service.[58]

SFMTA noted that of 37 schedule updates submitted by Tutor Perini between December 2014 and December 2017, 21 were rejected "due to multiple and repetitive issues that vary from incorrect working sequences to unrealistic forecasted completion dates to artificially steering the schedule longest path through certain portions of the project."[55]:8 Contrary to TPC's claims, SFMTA stated that ground conditions were as expected from preliminary surveys, but TPC's "mining productivity has not been as planned" and directed TPC to develop a recovery schedule. In January 2018, for example, TPC modified their construction sequence at Chinatown station and were able to shave 18 days off the schedule, changing the estimated revenue service date to November 22, 2019.[55]:8

Other issues

Residents and workers near the 4th Street portal and North Beach extraction sites noted an increase in the visible number of rats after construction began.[59][60]

Construction of the Union Square/Market Street station required closing Stockton Street just north of Market, which depressed traffic to retailers in Union Square.[61] During the excavation, workers accidentally breached a water main in July 2014, causing basement-level flooding in shops along Geary between Stockton and Grant.[62] The ensuing cleanup took several days and forced the businesses to close.[63] Since Stockton Street has been closed between Geary and Ellis, starting in 2014, construction is suspended in December and the area is transformed into a pedestrian plaza known as "Winter Walk." Some have called for Winter Walk to be made a permanent year-round fixture, but notable opposition included Rose Pak, who wanted to retain Stockton as a link from Market to Chinatown.[64]

Workers breached a natural gas pipeline in May 2015 while working on the Yerba Buena/Moscone station, forcing the evacuation of the nearby Yerba Buena Center for the Arts.[65]

Art

.jpg)

During construction, murals have been painted on the temporary fences erected around the construction sites.[66] Artworks include:

- "Panorama", by Kota Ezawa (Chinatown Fence, winter 2013/14)

- "Ellipsis in the Key of Blue", by Randy Colosky (Yerba Buena/Moscone fence, summer 2014)

- "One Hundred Years: History of the Chinese in America", by James Leong (Chinatown station site, 2012)[67]

Permanent installations are planned for each station.[68] Artworks are divided into "landmark" and "wayfinding" categories. Candidates were announced in July 2010[69] and the winning entrants were announced on August 5, 2010:[70][71][72]

- Chinatown[73]

- "Yang Ge Dance of Northeast China", by Yumei Hou (landmark); two large-scale laser-cut metal panels painted red, based on traditional Chinese paper cutting and featuring traditional folk heroes. One is 16 by 37 feet (4.9 m × 11.3 m), to be installed in the mezzanine landing, and the other is 30 by 35 feet (9.1 m × 10.7 m), to be installed in the ticketing hall.

- "Urban Archaeology", by Tomie Arai (wayfinding); a large mural measuring 100 feet (30 m) and varying in height between 4–9 feet (1.2–2.7 m) featuring images of the life and history of the Chinatown area rendered in architectural glass.

- "A Sense of Community", by Clare Rojas; a large tile mural based on Chinese textile samples arranged in a Cathedral Quilting pattern. The finished mural will be a semicircle measuring approximately 36 by 18 feet (11.0 m × 5.5 m)

- Union Square/Market Street[74]

- "Lucy in the Sky", by Erwin Redl (landmark); hundreds of 10 by 10 inches (250 mm × 250 mm) LED-array-illuminated translucent panels, programmed to change colors, display patterns, and animations.

- "Illuminated Scroll" (working title: "Reflected Loop"), by Jim Campbell and Werner Klotz (wayfinding); a stainless steel ribbon measuring approximately 250 feet (76 m) long and varying in width between 4–8 feet (1.2–2.4 m), winding overhead.

- "Convergence: Commute Patterns", by Hughen Starkweather; patterns on the glass deck and elevators.

- Yerba Buena/Moscone[75]

- "Node", by Roxy Paine, a 110-foot (34 m) tall sculpture shaped like a branch, tapering from a diameter of 48 inches (1,200 mm) at the base to 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm) at the peak.

- "Arc Cycle" (working title), by Catherine Wagner (landmark); photographs taken during the late 1970s during the construction of Moscone Center, rendered on etched granite panels approximately 10 by 12.5 feet (3.0 m × 3.8 m). One photograph will be rendered in art glass at the surface level station entry at 14 by 23 feet (4.3 m × 7.0 m).[76]

- "Face C/Z", by Leslie Shows; a photographic image of iron pyrite enlarged to 36 by 15 feet (11.0 m × 4.6 m) and rendered in glass, metal, gravel, and other materials.

- 4th and Brannan[77]

- "Microcosmic" (working title: "Microscopic"),[78] by Moto Ohtake; a kinetic sculpture approximately 14 by 17 feet (4.3 m × 5.2 m) atop a 40-foot (12 m) high pole, featuring 31 rotating points.

A planned installation for 59 bronze sculptures by Tom Otterness at the Moscone station as the wayfinding piece was canceled in November 2011 after it was publicized that Otterness had previously filmed himself in 1977 shooting a dog for the piece "Shot Dog Film".[79][80]

References

- ↑ Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (10 July 2017). "Central Subway project faces up to 10-month delay". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- 1 2 Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (25 July 2017). "Central Subway completion date delayed again". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ↑ Rhodes, Michael (February 9, 2010). "City Leaders Gather for Central Subway Groundbreaking Ceremony". Streetsblog SF. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- 1 2 Cabanatuan, Michael (June 24, 2014). "S.F. Central Subway's big dig done". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2014-06-25.

- ↑ "Central Subway Project" (PDF). SAN FRANCISCO COUNTY TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- 1 2 Matier, Phil; Ross, Andy (5 December 2017). "SF's Central Subway falling further behind schedule, builder warns". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017. (subscription required)

- ↑ "Central Subway will move San Francisco in right direction". San Francisco Examiner. October 14, 2012. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Quan, Holly (December 6, 2011). "San Francisco Commute Speeds Drop Dramatically". KPIX-TV CBS SF Bay Area. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ "East SoMa Area Plan". San Francisco General Plan. San Francisco Planning Department. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ↑ "Downtown Area Plan". San Francisco General Plan. San Francisco Planning Department. Archived from the original on 2012-12-08. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ↑ "Community Health Status Assessment: City and County of San Francisco" (pdf). San Francisco Department of Public Health. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- 1 2 "U.S. Transportation Secretary LaHood Announces $942.2 Million to Extend San Francisco's Third Street Light Rail System". Federal Transit Administration. Archived from the original on 2012-10-26. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ↑ "Central Subway Project Funding/Budget". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA). Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ↑ "MTA Board Selects Central Subway Alignment". Transbay Blog. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- 1 2 Nevius, C.W. (22 April 2013). "The hole in subway opponents' arguments". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Vega, Cecilia M. (February 20, 2008). "S.F. Chinatown subway plan gets agency's nod". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ "Central Subway Alignment". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA). Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ↑ Roberston, Michelle (26 January 2017). "A subterranean 'cathedral': Stunning new photos of Central Subway construction". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Central Subway Project, San Francisco". Railway Technology. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (26 November 2014). "Extending SF's Central Subway would draw riders, study says". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ King, John (3 December 2014). "Central Subway extension to Fisherman's Wharf makes sense". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (23 March 2000). "Transit Panel Readies $3.3 Billion Wish List for Gov. Davis / Hwy. 4, I-680 improvements among projects". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (17 December 2001). "Transit plan a commuter's dream / 'Baby bullet' trains, a new bus terminal, BART to Silicon Valley". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 Lee, Stephanie M. (14 March 2012). "SF Chinatown's Stockton could get more elbow room". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Tutor Perini (18 April 2013). "Proposal for Contract No. 1300" (PDF). Central Subway Blog. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- 1 2 Cabanatuan, Michael (21 May 2013). "S.F.'s Central Subway straining budget". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ "Central Subway: Visionary Project or Colossal Boondoggle?". Transbay Blog. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ↑ "Third Street Light Rail Project Environmental Impact Statement / Environmental Impact Report". ICF Kaiser Engineers, Inc., et al. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (11 October 2012). "Giant day for Central Subway". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Lochhead, Carolyn (19 January 2012). "Central Subway funds get a key OK". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Epstein, Edward (19 April 2000). "Even $5.6 Billion Plan Means Gridlock in S.F. Future, Experts Say / In next 30 years, city needs to pay more on transit". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- 1 2 Cabanatuan, Michael (11 June 2012). "S.F. Central Subway tunnel construction to begin". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (19 July 2012). "Central Subway work starts amid problems". San francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ "Mom Chung and Big Alma: The Central Subway's Tunnel Boring Machines" (PDF) (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency. 16 June 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ↑ Wildermuth, John (19 April 2013). "Central Subway workers prepare for boring machine". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Coté, John; Tucker, Jill (9 May 2013). "Mayor Lee excited about Central Subway". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ "TBM Mom Chung launches, beginning tunnel construction beneath SF". Central Subway Blog. July 26, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (6 August 2014). "Machines quietly tunneling in Muni's Central Subway project". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (July 19, 2012). "Central Subway work starts amid problems". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Coté, John (4 August 2012). "North Beach tunnel plan angers residents". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Matier, Phil; Ross, Andy (2 December 2012). "Muni subway plan to appease North Beach". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ↑ Riley, Neal (14 February 2013). "MTA reaches lease deal with Pagoda Palace". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ "Construction Update | July 04 – July 14". Central Subway Blog. July 3, 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- 1 2 Cabanatuan, Michael (May 19, 2015). "S.F. leaders tour completed Central Subway tunnel". SFGate. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (19 November 2014). "Controller says Central Subway on track — both budget and completion". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ Banchero, Rick (2 September 2015). "Muni, Traffic Impacts Ahead on a Laborious Labor Day Weekend". On Tap (blog). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Projects, Events to Heavily Impact Traffic and Transit this Labor Day Weekend" (PDF) (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. 2 September 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (5 November 2015). "Central Subway work to disrupt traffic for 8 days". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Central Subway Monthly Progress Report (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. January 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Central Subway Monthly Progress Report (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. July 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Central Subway Monthly Progress Report (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. January 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Central Subway Monthly Progress Report (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. July 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Central Subway Monthly Progress Report (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. January 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Central Subway Monthly Progress Report (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. July 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 Central Subway Monthly Progress Report (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. January 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (13 September 2017). "Central Subway could start partial service in time to serve Warriors' arena". SF Gate. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ↑ Phelan, Lori (11 December 2017). "Central Subway Program Director Accepts New Position at Caltrain" (Press release). SFMTA. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (3 April 2018). "San Francisco's Central Subway is getting closer to completion". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ Ho, Vivian (14 November 2013). "Rats scatter from Central Subway construction". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Ho, Vivian (3 April 2014). "North Beach rats may be result of Central Subway work". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Matier, Phil; Ross, Andy (29 September 2014). "Union Square merchants not digging new subway". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ Coté, John (12 July 2014). "Water main break floods Union Square retailers". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ Ho, Vivian (15 July 2014). "Crews cleaning up flooded Union Square stores". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael; Sernoffsky, Evan (22 November 2016). "Stockton Street becomes holiday pedestrian plaza — should closure be permanent?". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ↑ Green, Emily; Rubenstein, Steve (20 May 2015). "Streets reopen, gas leak capped in San Francisco". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Whiting, Sam (10 June 2014). "New Mural snakes along fence of Central Subway". Arts & Not (blog). San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Mural from CHSA Collection Featured at Central Subway Project Site" (Press release). Chinese Historical Society of America. 24 February 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Central Subway Public Art Program". San Francisco Arts Commission. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Public Art Proposal Display from July 9-16". Central Subway Blog. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Public Art Program Announces Winners". Central Subway Blog. 5 August 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Public Art Program Update". Central Subway Blog. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Central Subway Public Art Program". San Francisco Arts Commission. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ "Public Art Proposals: CTS". Central Subway Blog. 14 July 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Public Art Proposals: UMS". Central Subway Blog. 12 July 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ "Public Art Proposals: MOS". Central Subway Blog. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Wagner, Catherine (19 October 2011). "Final design drawings, Moscone Station public art, San Francisco" (PDF). City of San Francisco. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Horgos, Bonnie (11 November 2012). "Santa Cruz County Stories, Moto Ohtake: Local artist's sculptures juxtapose structure with chaos". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Ohtake, Moto. "Microcosmic: ARt Proposal for the 4th and Brannan Street Platform Station" (PDF). City of San Francisco. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ Sabatini, Joshua (16 September 2011). "Sculptor who killed dog set to make San Francisco Central Subway art". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Sabatini, Joshua (17 November 2011). "Dog-killer artist loses SF contract, keeps second". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Central Subway. |

- Central Subway – official home page

- "Central Subway". flickr. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- SFCTA Central Subway

- Alternatives. SFMTA.com.

- Purpose. SFMTA.com.

- Affected Environment. SFMTA.com.

- Chinatown Report. SF Chronicle. June 22, 2007.

- Central Subway. Fog City Journal.

- Push For Chinatown Central Subway. Amy Hollyfield, ABC (KGO-TV). March 20, 2007.

- Central Subway an Alternate Proposal. RescueMuni.org.

- Time-lapse films of Central Subway construction by SFMTA photographer Robert Pierce

Fact sheets

- "Project Overview" (PDF). Central Subway Blog. October 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

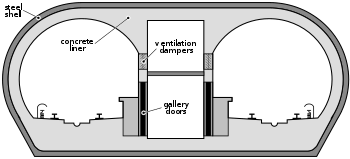

- "Central Subway Tunnel" (PDF). Central Subway Blog. June 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Chinatown Station" (PDF). Central Subway Blog. March 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Union Square/Market Street Station" (PDF). Central Subway Blog. April 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2017.