Church of Saint Sava

| Church of Saint Sava | |

|---|---|

| Храм Светог Саве / Hram Svetog Save | |

Church of Saint Sava | |

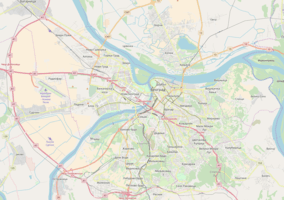

Church of Saint Sava Location within Belgrade | |

| 44°47′53.1″N 20°28′6.78″E / 44.798083°N 20.4685500°ECoordinates: 44°47′53.1″N 20°28′6.78″E / 44.798083°N 20.4685500°E | |

| Location | Krušedolska 2a, Vračar, Belgrade |

| Country | Serbia |

| Denomination | Serbian Orthodox |

| Website |

www |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) |

Aleksandar Deroko Branko Pešić |

| Architectural type |

Serbo-Byzantine Neo-Byzantine |

| Years built | 1935–present |

| Groundbreaking | 10 May 1935 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 10,800 (inner)[1] |

| Length | 91 m (299 ft)[1] |

| Width | 81 m (266 ft)[1] |

| Height | 79 m (259 ft)[1] |

| Other dimensions |

5,400 m2 (58,125 sq ft) (combined floor area)[2][3][1] 5,900 m2 (63,507 sq ft) (exterior)[3] |

| Floor area | 3,500 m2 (37,674 sq ft) |

|

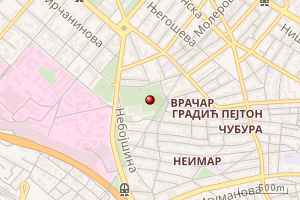

| Location within Vračar |

The Church of Saint Sava (Serbian: Храм светог Саве/Hram svetog Save[a], literal translation into English: "The Temple of Saint Sava") is a Serbian Orthodox church located on the Vračar plateau in Belgrade. It is one of the largest Orthodox churches in the world[4] and ranks among the largest church buildings in the world.

The church is dedicated to Saint Sava, the founder of the Serbian Orthodox Church and an important figure in medieval Serbia. It is built on the Vračar plateau, on the location where his remains were burned in 1595 by Ottoman Grand Vizier Sinan Pasha. From its location, it dominates Belgrade's cityscape, and is perhaps the most monumental building in the city.

History

Background

In 1594, Serbs rose up against Ottoman rule in Banat, during the Long War (1591–1606)[5] which was fought at the Austrian-Ottoman border in the Balkans. The Serbian patriarchate and rebels had established relations with foreign states,[5] and had in a short time captured several towns, including Vršac, Bečkerek, Lipova, Titel and Bečej, although the uprising was quickly suppressed. The rebels had, in the character of a holy war, carried war flags with the icon of Saint Sava.[6]

The war banners had been consecrated by Patriarch John I Kantul, whom the Ottoman government later had hanged in Istanbul. Ottoman Grand Vizier Sinan Pasha ordered that the sarcophagus and relics of Saint Sava located in the Mileševa monastery be brought by military convoy to Belgrade.[5][6] Along the way, the Ottoman convoy had people killed in their path so that the rebels in the woods would hear of it.[6] The relics were publicly incinerated by the Ottomans on a pyre on the Vračar plateau, and the ashes scattered, on 27 April 1595.[5] According to Nikolaj Velimirović the flames were seen over the Danube.[6]

Planning

In 1895, three hundred years after the burning of Saint Sava's remains, the Society for the Construction of the Church of Saint Sava on Vračar was founded in Belgrade. Its goal was to build a temple on the place of the burning. A small church was built at the future place of the temple, and it was later moved so the construction of the temple could begin.

In 1905, a public contest was launched to design the church; all five applications received were rejected as not being good enough. Soon, the breakout of the First Balkan War in 1912, and subsequent Second Balkan War and First World War stopped all activities on the construction of the church.

After the war, in 1919, the Society was re-established. New appeals for designs were made in 1926; this time, it received 22 submissions. Though the first and third prize were not awarded, the second-place submission by architect Aleksandar Deroko was selected.

Building

Forty years after the initial idea, construction of the church began on 10 May 1935, 340 years after the burning of Saint Sava's remains. The cornerstone was laid by Metropolitan Gavrilo of Montenegro, (the future Serbian Patriarch Gavrilo V). The project was designed by Aleksandar Deroko and Bogdan Nestorović, aided by civil engineer Vojislav Zađina. The work lasted until Second World War Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941.

The church's foundation had been completed, and the walls erected to the height of 7 and 11 meters. After the 1941 bombing of Belgrade, work ceased altogether. The occupying German army used the unfinished church as Wehrmacht's parking lot, while in 1944 the Red Army, and later the Yugoslav People's Army used it for the same purpose. After that, it was used for storage by various companies. The Society for Building of the Church ceased to exist and has not been revived. Children who grew up in the vicinity, including the future President of Serbia Boris Tadić, didn't know the intended purpose of the unfinished construction, so they played inside thinking it was a ruin of some old castle.[7]

In 1958, Serbian Patriarch German renewed the idea of building the church. After 88 requests for the continuation of the building, of which 82 were sent to the President of Yugoslavia Josip Broz Tito to which Tito never personally replied. Permission for the continuation of building was granted in 1984 when patriarch talked to Dušan Čkrebić, President of Presidency of Serbia.[7] Architect Branko Pešić was selected as new architect of the church. He remade the original projects to make better use of new materials and building techniques. Construction of the building began again on 12 August 1985. The walls were erected to full height of 40 meters.

The greatest achievement of the construction process was lifting of the 4,000 ton central dome, which was built on the ground, together with the copper plate and the cross, and later lifted onto the walls. The lifting, which took forty days with the especially constructed hydraulic machines, was finished on 26 June 1989.

After the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, the works were halted again. Patriarch Pavle, known for his asceticism, thought that such an expensive works are inappropriate when people are beaten and impoverished. After becoming a prime minister in 2001, Zoran Đinđić talked with patriarch and convinced him to continue the works.[7] As of 2017, the exterior of the church is complete. The bells and windows had been installed, and the façade completed. The Russian Academy of Arts under the guidance of Nikolay Mukhin is currently working on the internal decoration.[8] On 22 February 2018, during the presentation of the new internal decoration, the decorated cupola was donated to the Serbian Orthodox Church.[9]

Architecture

The church is centrally planned, having the form of a Greek Cross. It has a large central dome supported on four pendentives and buttressed on each side by a lower semi-dome over an apse. Beneath each semi-dome is a gallery supported on an arcade.

The dome is 70 m (230 ft) high, while the main gold plated cross is another 12 m (39 ft) high, which gives a total of 82 m (269 ft) to the height Church of Saint Sava. The peak is 134 m (440 ft) above the sea level (64 m (210 ft) above the Sava river); therefore the church holds a dominant position in Belgrade's cityscape and is visible from all approaches to the city.

The church is 91 m (299 ft) long from east to west, and 81 m (266 ft) from north to south. It is 70 m (230 ft) tall, with the main gold-plated cross extending for 12 m (39 ft) more. Its domes have 18 more gold-plated crosses of various sizes, while the bell towers have 49 bells of the Austrian Bell Foundry Grassmayr.

It has a surface area of 3,500 m2 (37,674 sq ft) on the ground floor, with three galleries of 1,500 m2 (16,146 sq ft) on the first level, and a 120 m2 (1,292 sq ft) gallery on the second level. The Church can receive 10,000 faithful at any one time. The choir gallery seats 800 singers. The basement contains a crypt, the treasury of Saint Sava, and the grave church of Saint Lazar the Hieromartyr, with a total surface of 1,800 m2 (19,375 sq ft) .

The central dome mosaic depicts the Ascension of Jesus and represents Resurrected Christ, sitting on a rainbow and right hand raised in blessing, surrounded by four angels, Apostles and Theotokos. This composition is inspired by mosaic in main dome of St Mark's Basilica in Venice. The lower sections are influenced by the Gospel of Luke and the first narratives of the Acts of the Apostles. The texts held by the angels are written in the Church Slavonic language, while the names of the depicted persons are written in Greek. First points to the pan-Slavic sentiment while the latter connects it to the Byzantine traditions. The total painted area of the dome is 1,230 m2 (13,200 sq ft). It is one of the largest curved area decorated with the mosaic technique and when the work is completely finished, Saint Sava will be the largest church ornamented this way. The mosaic was made for a year in Russia, during 2016 and 2017. It was then cut and transported by special trucks to Belgrade. Total weight of the mosaic is 40 tons and it was placed on the dome from May 2017 to February 2018.[10]

Gallery

Interior (unfinished).

Interior (unfinished). Aerial view by night

Aerial view by night Parish home

Parish home Monument to Karadjordje, the founder of modern Serbia

Monument to Karadjordje, the founder of modern Serbia Church of Saint Sava and the National Library of Serbia

Church of Saint Sava and the National Library of Serbia Church of Saint Sava, at night

Church of Saint Sava, at night

See also

Annotations

- ^ The church building is sometimes referred to as a "cathedral" because of its size although it is not a cathedral in the technical ecclesiastical sense, as it is not the seat of a bishop (seat of the Metropolitan bishop of Belgrade is St. Michael's Cathedral). In Serbian it is called hram (temple), which is another name for a church in Eastern Orthodoxy.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Димензије и архитектонске карактеристике - Храм Светог Саве" [Dimensions and Architectural Features]. - Hram Svetog Save.

- ↑ Nave & Altar = 3,650 m²

Three Narthex = 1,750 m². Stairs ~500 m². - 1 2 "Рад на припремама пројекта за храм - Храм Светог Саве" [Working on the preparations for the temple project]. - Hram Svetog Save.

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton; Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World, Second Edition: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. pp. 511–12. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Mitja Velikonja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Nikolaj Velimirović (January 1989). The Life of St. Sava. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-88141-065-5.

- 1 2 3 Aleksandar Apostolovski (27 January 2013), "Legenda o Hramu Svetog Save", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ ОФОРМЛЕНИЕ ВНУТРЕННЕГО УБРАНСТВА ХРАМА СВЯТОГО САВВЫ В БЕЛГРАДЕ

- ↑ Торжественная церемония передачи Сербской Православной церкви мозаичного убранства главного купола Храма Святого Саввы в Белграде.

- ↑ Ana Vuković (18 February 2018). "Мозаик од 40 тона украсио куполу" [40 tons mosaic ornamented the dome]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1064 (in Serbian). pp. 14–19.

Sources

- Milanović, Ljubomir (2010). "Materializing authority: the church of Saint Sava in Belgrade and its architectural significance". Serbian Studies. NASSS. 24 (1): 63–81.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple of Saint Sava. |

- Official site (in Serbian)

- Webcam