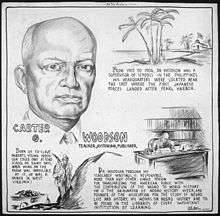

Carter G. Woodson

| Carter G. Woodson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Carter Godwin Woodson December 19, 1875 New Canton, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died |

April 3, 1950 (aged 74) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Education |

Berea College (B.Litt 1903) University of Chicago (A.B., A.M. 1908) Harvard University (Ph.D. 1912) |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Known for |

Association for the Study of Negro Life and History; Negro History Week; The Journal of Negro History |

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875 – April 3, 1950)[1] was an American historian, author, journalist and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He was one of the first scholars to study African-American history. A founder of The Journal of Negro History in 1916, Woodson has been cited as the "father of black history".[2] In February 1926 he launched the celebration of "Negro History Week", the precursor of Black History Month.[3]

Early life and education

Carter G. Woodson was born in Buckingham County, Virginia[4] on December 19, 1875, the son of former slaves, James and Eliza Riddle Woodson.[5] His father helped Union soldiers during the Civil War and moved his family to West Virginia when he heard that Huntington was building a high school for blacks.

Coming from a large, poor family, Carter Woodson could not regularly attend school. Through self-instruction, he mastered the fundamentals of common school subjects by the age of 17. Wanting more education, he went to Fayette County to earn a living as a miner in the coal fields, and was able to devote only a few months each year to his schooling.

In 1895, at the age of 20, Woodson entered Douglass High School, where he received his diploma in less than two years.[6] From 1897 to 1900, Woodson taught at Winona in Fayette County. In 1900 he was selected as the principal of Douglass High School. He earned his Bachelor of Literature degree from Berea College in Kentucky in 1903 by taking classes part-time between 1901 and 1903. From 1903 to 1907, Woodson was a school supervisor in the Philippines.

Woodson later attended the University of Chicago, where he was awarded an A.B. and A.M. in 1908. He was a member of the first black professional fraternity Sigma Pi Phi[7] and a member of Omega Psi Phi. He completed his PhD in history at Harvard University in 1912, where he was the second African American (after W. E. B. Du Bois) to earn a doctorate.[8] His doctoral dissertation, The Disruption of Virginia, was based on research he did at the Library of Congress while teaching high school in Washington, D.C. After earning the doctoral degree, he continued teaching in public schools, later joining the faculty at Howard University as a professor, and served there as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

Career

Convinced that the role of his own people in American history and in the history of other cultures was being ignored or misrepresented among scholars, Woodson realized the need for research into the neglected past of African Americans. Along with William D. Hartgrove, George Cleveland Hall, Alexander L. Jackson, and James E. Stamps, he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History on September 9, 1915, in Chicago.[9] That was the year Woodson published The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. His other books followed: A Century of Negro Migration (1918) and The History of the Negro Church (1927). His work The Negro in Our History has been reprinted in numerous editions and was revised by Charles H. Wesley after Woodson's death in 1950.

In January 1916, Woodson began publication of the scholarly Journal of Negro History. It has never missed an issue, despite the Great Depression, loss of support from foundations, and two World Wars. In 2002, it was renamed the Journal of African American History and continues to be published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH).

Woodson stayed at the Wabash Avenue YMCA during visits to Chicago. His experiences at the Y and in the surrounding Bronzeville neighborhood inspired him to create the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History), which ran conferences, published The Journal of Negro History, and "particularly targeted those responsible for the education of black children".[10] Another inspiration was John Wesley Cromwell's 1914 book, The Negro in American History: Men and Women Eminent in the Evolution of the American of African Descent.[11]

Woodson believed that education and increasing social and professional contacts among blacks and whites could reduce racism and he promoted the organized study of African-American history partly for that purpose. He would later promote the first Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in 1926, forerunner of Black History Month.[12] The Bronzeville neighborhood declined during the late 1960s and 1970s like many other inner-city neighborhoods across the country, and the Wabash Avenue YMCA was forced to close during the 1970s, until being restored in 1992 by The Renaissance Collaborative.[13]

He served as Academic Dean of the West Virginia Collegiate Institute, now West Virginia State University, from 1920 to 1922.[14]

He studied many aspects of African-American history. For instance, in 1924, he published the first survey of free black slaveowners in the United States in 1830.[15]

NAACP

Woodson became affiliated with the Washington, D.C. branch of the NAACP, and its chairman Archibald Grimké. On January 28, 1915, Woodson wrote a letter to Grimké expressing his dissatisfaction with activities and making two proposals:

- That the branch secure an office for a center to which persons may report whatever concerns the black race may have, and from which the Association may extend its operations into every part of the city; and

- That a canvasser be appointed to enlist members and obtain subscriptions for The Crisis, the NAACP magazine edited by W. E. B. Du Bois.

Du Bois added the proposal to divert "patronage from business establishments which do not treat races alike," that is, boycott businesses. Woodson wrote that he would cooperate as one of the twenty-five effective canvassers, adding that he would pay the office rent for one month. Grimké did not welcome Woodson's ideas.

Responding to Grimké's comments about his proposals, on March 18, 1915, Woodson wrote:

I am not afraid of being sued by white businessmen. In fact, I should welcome such a law suit. It would do the cause much good. Let us banish fear. We have been in this mental state for three centuries. I am a radical. I am ready to act, if I can find brave men to help me.[16]

His difference of opinion with Grimké, who wanted a more conservative course, contributed to Woodson's ending his affiliation with the NAACP.

Black History Month

Woodson devoted the rest of his life to historical research. He worked to preserve the history of African Americans and accumulated a collection of thousands of artifacts and publications. He noted that African-American contributions "were overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them."[17] Race prejudice, he concluded, "is merely the logical result of tradition, the inevitable outcome of thorough instruction to the effect that the Negro has never contributed anything to the progress of mankind."[17]

In 1926, Woodson pioneered the celebration of "Negro History Week",[18] designated for the second week in February, to coincide with marking the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.[19] However, it was the Black United Students and Black educators at Kent State University that founded Black History Month, on February 1, 1970.[20]

Colleagues

Woodson believed in self-reliance and racial respect, values he shared with Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican activist who worked in New York. Woodson became a regular columnist for Garvey's weekly Negro World.

Woodson's political activism placed him at the center of a circle of many black intellectuals and activists from the 1920s to the 1940s. He corresponded with W. E. B. Du Bois, John E. Bruce, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, Hubert H. Harrison, and T. Thomas Fortune, among others. Even with the extended duties of the Association, Woodson was able to write academic works such as The History of the Negro Church (1922), The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), and others which continue to have wide readership.

Woodson did not shy away from controversial subjects, and used the pages of Black World to contribute to debates. One issue related to West Indian/African-American relations. He summarized that "the West Indian Negro is free", and observed that West Indian societies had been more successful at properly dedicating the necessary amounts of time and resources needed to educate and genuinely emancipate people. Woodson approved of efforts by West Indians to include materials related to Black history and culture into their school curricula.

Woodson was ostracized by some of his contemporaries because of his insistence on defining a category of history related to ethnic culture and race. At the time, these educators felt that it was wrong to teach or understand African-American history as separate from more general American history. According to these educators, "Negroes" were simply Americans, darker skinned, but with no history apart from that of any other. Thus Woodson's efforts to get Black culture and history into the curricula of institutions, even historically Black colleges, were often unsuccessful.

Death and legacy

Woodson died suddenly from a heart attack in the office within his home in the Shaw neighborhood of Washington, D.C., on April 3, 1950, at the age of 74. He is buried at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland

The time that schools have set aside each year to focus on African-American history is Woodson's most visible legacy. His determination to further the recognition of the Negro in American and world history, however, inspired countless other scholars. Woodson remained focused on his work throughout his life. Many see him as a man of vision and understanding. Although Woodson was among the ranks of the educated few, he did not feel particularly sentimental about elite educational institutions. The Association and journal that he started are still operating, and both have earned intellectual respect.

Woodson's other far-reaching activities included the founding in 1920 of the Associated Publishers, the oldest African-American publishing company in the United States. This enabled publication of books concerning blacks that might not have been supported in the rest of the market. He founded Negro History Week in 1926 (now known as Black History Month). He created the Negro History Bulletin, developed for teachers in elementary and high school grades, and published continuously since 1937. Woodson also influenced the Association's direction and subsidizing of research in African-American history. He wrote numerous articles, monographs and books on Blacks. The Negro in Our History reached its 11th edition in 1966, when it had sold more than 90,000 copies.

Dorothy Porter Wesley recalled: "Woodson would wrap up his publications, take them to the post office and have dinner at the YMCA. He would teasingly decline her dinner invitations saying, 'No, you are trying to marry me off. I am married to my work'".[21] Woodson's most cherished ambition, a six-volume Encyclopedia Africana, was incomplete at the time of his death.

Honors and tributes

- In 1926, Woodson received the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Spingarn Medal.

- The Carter G. Woodson Book Award was established in 1974 "for the most distinguished social science books appropriate for young readers that depict ethnicity in the United States."[22]

- The U.S. Postal Service issued a 20-cent stamp honoring Woodson in 1984.[23]

- In 1992, the Library of Congress held an exhibition entitled Moving Back Barriers: The Legacy of Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had donated his collection of 5,000 items from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries to the Library.

- His Washington, D.C. home has been preserved and designated the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Carter G. Woodson on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[24]

- On February 1, 2018, he was honored with a Google Doodle.[25]

Places named after Woodson

California

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School in Los Angeles.

- Carter G. Woodson Public Charter School in Fresno.

Florida

- Carter G. Woodson Park, in Oakland Park.[26]

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School was located in Oakland Park. It was closed in 1965 when the Broward County Public Schools system was desegregated.

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American Museum in St. Petersburg.

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School in Jacksonville.

Georgia

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary in Atlanta.

Illinois

- Carter G. Woodson Regional Library in Chicago.

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in Chicago.

- Carter G. Woodson Library of Malcolm X College in Chicago

Indiana

- Carter G. Woodson Library in Gary.

Kentucky

- Carter G. Woodson Academy in Lexington.

- Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education, Berea College, in Berea.[27]

Louisiana

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in New Orleans.

- Carter G. Woodson Liberal Arts Building at Grambling State University, built in 1915, in Grambling.

Maryland

Minnesota

- Woodson Institute for Student Excellence in Minneapolis.

New York

North Carolina

- Carter G. Woodson Charter School in Winston-Salem.

Texas

- Woodson K-8 School in Houston.

- Carter G. Woodson Park in Odessa

Virginia

- The Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in Hopewell.

- C.G. Woodson Road in his home town of New Canton.

- Carter G. Woodson Education Complex in Buckingham County, built in 2012.

Washington, D.C.

- Carter G. Woodson Junior High School was named for him. It currently hosts Friendship Collegiate Academy Public Charter School.

- The Carter G. Woodson Memorial Park is between 9th Street, Q Street and Rhode Island Avenue, NW. The park contains a cast bronze sculpture of the historian by Raymond Kaskey.

- The Carter G. Woodson Home, a National Historic Site, is located at 1538 9th St., NW, Washington, D.C.[29]

West Virginia

- Carter G. Woodson Jr. High School (renamed McKinley Jr. High School after integration in 1954) in St. Albans, built in 1932.

- Carter G. Woodson Avenue (also known as 9th Avenue) in Huntington. Notably, Woodson's alma mater, Douglass High School, is located between Carter G. Woodson Avenue and 10th Avenue in the 1500 block.

Selected works

- A century of negro migration. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1918. OCLC 79947665.

- The Education of the Negro prior to 1861. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1919. OCLC 593592787.

- The history of the Negro church. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1921. OCLC 506124215.

- The negro in our history. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1922. OCLC 506124204.

- Free Negro owners of slaves in the United States in 1830, together with Absentee ownership of slaves in the United States in 1830. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1924. OCLC 802300957.

- Free Negro heads of families in the United States in 1830 : together with a brief treatment of the free Negro. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1925. OCLC 176986298.

- Preview of Negro orators and their orations. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1925. OCLC 703518974.

- The mind of the Negro as reflected in letters written during the crisis, 1800–1860. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1926. OCLC 558188512.

- Negro makers of history. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1928. OCLC 558190211.

- African myths and folk tales. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. 2009 [1928]. ISBN 9780486114286. OCLC 853448285.

- The Rural Negro. HathiTrust. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1930. OCLC 613261827.

- Greene, Lorenzo J.; Woodson, Carter G. (1930). The Negro wage earner. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. OCLC 558574532.

- The Mis-Education of the Negro. Lanham: Dancing Unicorn Books. 2017 [1933]. ISBN 9781515415534. OCLC 987740119.

- The Negro professional man and the community, with special emphasis on the physician and the lawyer. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1934. OCLC 612967753.

- Woodson, Carter Godwin; Wesiley, Charles H. (1959) [1935]. The story of the Negro retold (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. OCLC 558574303.

- The African background outlined : or, Handbook for the study of the Negro (DjVu). Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc. 2006 [1936]. OCLC 219632552.

- African heroes and heroines. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1939. OCLC 643987347.

- Grimké, F.J. (1942). Woodson, Carter Godwin, ed. The works of Francis J. Grimke. The Associated publishers, Inc. OCLC 600171452.

- Woodson, Carter (2008). Scott, Daryl Michael, ed. Carter G. Woodson's appeal. Washington, DC: ASALH Press. ISBN 9780976811190. OCLC 922360363.

See also

References

- ↑ Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. The correspondence of W. E. B. Du Bois, Volume 3. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 282. ISBN 1-55849-105-8. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ↑ Bennett, Jr., Lerone (2005). "Carter G. Woodson, Father of Black History". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on April 1, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ↑ Daryl Michael Scott, "The History of Black History Month" Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., on ASALH website.

- ↑ "Virginian Started Negro History Week in 1926". Norfolk (VA) New Journal and Guide, February 9, 1957, p. 11.

- ↑ Betty J. Edwards, "He Made World Respect Negroes". Chicago Defender, February 8, 1965, p. 9.

- ↑ Maurice F. White, "Dr. Carter G. Woodson History Week Founder". Cleveland Call and Post, February 16, 1963, p. 3C.

- ↑ "1904–2004: the Boule at 100: Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity holds centennial celebration". Ebony. September 2004. Archived from the original on November 23, 2004. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ↑ "The End of Black History Month?" Newsweek, January 28, 2010.

- ↑ Scott, Daryl Michael. "The founding of the association September 9, 1915". Carter G. Woodson Center. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ Claire Corbould, Becoming African Americans: The Public Life of Harlem 1919–1939, Cambridge, Massachusetts/London, England: Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 88.

- ↑ Karen Juanita Carrillo, African American History Day by Day: A Reference Guide to Events. ABC-CLIO, August 22, 2012, pp. 262–263.

- ↑ "Young Men's Christian Association - Wabash Avenue Records", Black Metropolis Research Consortium, University of Chicago.

- ↑ "History", The Renaissance Collaborative.

- ↑ Osborne, Kellie (January 29, 2015). "West Virginia State University Celebrates Black History Month with Series of Events". West Virginia State University. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ Charles H. Wesley, "Carter G. Woodson as a Scholar", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 36, No. 1 (January 1951), pp. 12–24, in JSTOR.

- ↑ Cobb, Jr., Charles E. (January 1, 2008). On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail. Algonquin Books. p. 28. ISBN 9781565124394.

- 1 2 Current Biography 1944, p. 742.

- ↑ Corbould (2009), p. 106.

- ↑ Delilah L. Beasley, "Activities Among Negroes, Oakland Tribune, February 14, 1926, p. X–5.

- ↑ Wilson, Milton. "Involvement/2 Years Later: A Report On Programming In The Area Of Black Student Concerns At Kent State University, 1968–1970". Special Collections and Archives: Milton E. Wilson, Jr. papers, 1965–1994. Kent State University. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ↑ Jacqueline Trescott, "Black History's Early Champion", The Washington Post, February 10, 1992.

- ↑ "About the Carter G. Woodson Book Award". National Council for the Social Studies. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Stamp Series". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- ↑ "Celebrating Carter G. Woodson". Google Doodles. February 1, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Dr. Carter G. Wilson Festival". The City of Oakland Park. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education". Berea College. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Carter G. Woodson Children's Park : NYC Parks".

- ↑ "Directions – Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site". National Park Service. January 31, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

Further reading

- Alridge, Derrick P. "Woodson, Carter G." in Simon J. Bronner (ed.), Encyclopedia of American Studies (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), online.

- Dagbovie, Pero Gaglo. The Early Black History Movement, Carter G. Woodson, and Lorenzo Johnston Greene (University of Illinois Press, 2007).

- Goggin, Jacqueline Anne. Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History (LSU Press, 1997).

- Meier, August, and Elliott Rudwick. Black History and the Historical Profession, 1915–1980 (University of Illinois Press, 1986).

- Roche, A. "Carter G. Woodson and the Development of Transformative Scholarship", in James Banks (ed.), Multicultural Education, Transformative Knowledge, and Action: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (Teachers College Press, 1996).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Carter G. Woodson |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carter Godwin Woodson. |

- The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH)

- Audiobook version of "The Mis-Education of the Negro"

- Homepage for Carter G. Woodson's Appeal

- Daryl Michael Scott, "The History of Black History Month", ASALH website

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American History Museum

- "Some St. Albans Schools over the years", St. Albans Historical Society.

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American Museum

- Dr Carter Godwin Woodson at Find a Grave

Woodson's writings

- Works by Carter G. Woodson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Carter G. Woodson at Internet Archive

- The History of the Negro Church. ISBN 0-87498-000-3.

- Mis-Education of the Negro. ISBN 0-9768111-0-3.

Other information about Woodson

- "Dr. Carter Godwin Woodson & the Observance of African History"

- Library of Congress Initiates Traveling Exhibits Program

- Library of Congress Traveling Exhibit re Dr. C.G. Woodson

- Carter G. Woodson Collection of Negro Papers and Related Documents

- Carter G. Woodson Wax Figure at the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum