Butia odorata

| Butia odorata | |

|---|---|

| Butia odorata, Tresco, Isles of Scilly, UK | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Monocots |

| (unranked): | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Subfamily: | Arecoideae |

| Tribe: | Cocoseae |

| Genus: | Butia |

| Species: | B. odorata |

| Binomial name | |

| Butia odorata (Barb.Rodr.) Noblick [2011] | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Butia odorata, also known as the South American jelly palm,[2] jelly palm,[2] or pindo palm,[2] is a Butia palm native to southernmost Brazil and Uruguay.[3] This slow-growing palm grows up to 6m (exceptionally 8m). It is identifiable by its feather palm pinnate leaves that arch inwards towards a thick stout trunk.

Nomenclature

These palms are often called Butia capitata in horticulture. It was seen as a synonym of that more tropical species until 2011, and many botanical gardens, collectors, and those in the nursery trade have not yet changed their labelling. Even more confusingly; plants with the invented name B. capitata var. odorata have circulated in the horticultural trade which were actually the in 2010 newly named B. catarinensis, from further north along the Brazilian coast.[3][4][5][6]

In Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, local vernacular names for this plant in Portuguese are butiá-da-praia,[7] or just butiá.[7][8]

Etymology

The specific epithet odorata is derived from the Latin word for 'perfumed' and was chosen by João Barbosa Rodrigues in 1891 to reflect the highly aromatic nature of the fruit, considered among the best palm fruit for consumption in Brazil at the time.[3]

Taxonomy

Until 2011 this species was lumped together with Butia capitata, a species first described by Karl Friedrich Philipp von Martius in 1826 in montane grasslands in the inner country in Minas Gerais.[6][9] During fieldwork in the southeast of the state of Bahia, Larry R. Noblick observed the real B. capitata in situ, and being quite familiar with cultivated B. odorata in Florida where he worked, and having visited the coastal population in 1996, became convinced that they could not represent one of two very disjunct populations of the same species. Noblick incorrectly attempted to separate the taxa twice before finally succeeding in 2011, choosing the oldest name which had unambiguously been given to this population: Cocos odorata by João Barbosa Rodrigues (C. pulposa was described in the same work, but O comes before P in the alphabet, so C. odorata has priority).[3][6]

Odoardo Beccari subsumed this taxon as a variety under B. capitata in 1916 (as B. capitata var. odorata) along with a number of other taxa such as Cocos pulposa, C. elegantissima, C. erythrospatha and C. lilaceiflora, which he all made different varieties of B. capitata. He also named two new taxa as varieties of B. capitata: B. capitata var. subglobosa and B. capitata var. virescens.

In 1936 Liberty Hyde Bailey added two more varieties, B. capitata var. nehrlingiana and B. capitata var. strictior, B. capitata thus having ten different varieties at the time (see below). All except the nominate form are now considered synonyms of B. odorata.

In 1970 Sidney Fredrick Glassman moved this taxon (as B. capitata), along with all other Butia, to Syagrus,[10] but in 1979 he changed his mind and moved everything back.[11]

Description

Description

Habitus

This is a solitary-trunked palm with a stout erect to slightly inclined trunk, occasionally being subterranean, growing up to 2 to 10m high and 0.32 to 0.6m in diameter.[3][7] The trunks narrow to 20cm diameter towards the crown.[8]

Leaves

It has 13 to 32 pinnate, glaucous to dark-green coloured leaves arching down towards the trunk and arranged spirally around the crown.[3][7] The petiole is 30-75cm long, 1-1.2cm thick, 3.3-3.9cm wide, and has both stiff rigid fibres and spines up to 5cm long along the margins (edges) of the petiole.[3][8] The top of the petiole is flat or slightly convex, the underside is rounded.[8] The rachis of the leaf is 70-200cm long and has 35 to 60,[3] exceptionally 66,[8] pairs of pinnae (leaflets). Unlike other species of Butia, these are inserted in groups of 2 to 4 at slightly divergent angels along the rachis, but without giving the leaf a plumose aspect such as in Syagrus.[3][8] The pinnae are clustered slightly together near the base of the leaf blade.[8] These pinnae are opposite each other in a pair; each pair forms a neat 'V'-shape. The pinnae in the middle of the leaf blade are 31-60cm long and 1.2-2.5cm wide.[3] Basal pinnae are 30-40cm long and 0.3-0.6cm wide; apical pinnae are 18-22cm long and 0.4-0.5cm wide.[8]

Flowers

The developing inflorescence is protected in a woody spathe, 60-180cm in total length, which is usually hairless but may rarely be densely pruinose (covered in waxy flakes) or tomentose (furry); the spathe has a swollen part at the end 33-150cm long and 6-16cm wide, and ends in a sharp apex (tip). The inflorescence is branched to the first order. The rachis of the inflorescence is 20-104cm long and has 35-141 rachillae (flowering branches) 15-132cm in length.[3] The flowers may be coloured yellow, reddish-orange, purple, yellow & purple, or greenish-yellow.[3][8] The pistillate (female) flowers are 5-6mm in length; the staminate (male) flowers are 5-7mm in length.[3]

Like all species of Butia studied, this species has relatively larger pollen grains than that of other genera of palm present in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. These grains are bilaterally symmetrical, suboblate, monosulcate, and with the end piriform (pear-shaped). The surface is covered in minute 2μm-large reticulate patterns.[7]

Fruit

The fruit are usually wider than they are long. They are very variable in size; most fruit are 2-3.5cm by 1.4-4.3cm. The ripe fruit have a persistent perianth and may be coloured yellow, orange, red, greenish-yellow or purple. The flesh is often yellow but may also be coloured in different hues.[3] The taste is variable, generally sweet and sour, but may be more of one or the other depending on the tree.[3][8] The fruits are highly aromatic.[6] It has a hard nut which is usually round in shape, sometimes more ovoid, 1.3-2.2cm by 1.3-2cm in size, and containing 1 to 3 seeds and a homogeneous endosperm.[3]

Similar species

It is similar to B. capitata, a smaller plant of the inland cerrado with a less thick trunk and which is not hardy. It has much more elongated, less globose, fruit, and can also be distinguished by tiny details of the leaves.[3][4]

Infraspecific Variability

Although palms outside of South America appear rather the same, they exhibit much more variability in their native homeland. Many of these variable forms were originally described as distinct species. Odoardo Beccari subsumed these as varieties of Butia capitata in 1916.[3]

Hybrids

×Butyagrus nabonnandii (Prosch.) Vorster (Mule palm) - This is a hybrid of Butia odorata with Syagrus romanzoffiana found both naturally in the wild as well as in cultivation, it was first described from garden examples in Europe.[3][12]

Distribution

It is native to southern Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, from the municipalities of Palmares do Sul and Porto Alegre south to Treinta y Tres and Rocha Department in northern Uruguay.[3][13] It grows from 0-500m in altitude.[13]

Bauermann et al. investigated the possibility of using palm pollen, including this species, in palynology, in order to try to provide more detail about the ancient changes in habitat in the state Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil by tracking the changes in distribution and abundance of the palms, but were unable to provide much detail on the subject.[7]

Habitat

It is distributed in a band along the coast of southernmost Brazil, extending into Uruguay. In this region it is found in restinga habitat in fields on top of the hills hugging the coast.[3] It may also occur in grasslands (pampa), seasonally semi-deciduous Atlantic forest, and rocky outcrops.[8] It grows in sandy and rocky soils which are often dry, such as stabilised dune formations. It does not occur in more humid habitats.[7] It commonly is found growing in small aggregated clusters;[3][7] these palm groves are known locally as butiazais or butiatubas.[7]

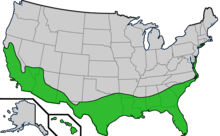

Non-native distribution

Despite being extensively planted in the region, this species is rarely recorded as escaping from gardens or naturalising in Florida and Georgia in the United States, and as of 2018 establishing populations are unknown.

In 2000 in Flora of North America Scott Zona stated that B. odorata showed little inclination for escaping cultivation,[14] but as of 2018 the USDA PLANTS database has it is as naturalized in the states of Florida, North and South Carolina of the United States.[15]

In 1996 the unpublished Flora of the Carolinas and Virginia, used as the reference in the PLANTS database, stated the species (as B. capitata) to be present in coastal North and South Carolina.[15] In 2004, 2005 & 2008 the same flora, expanded to Georgia by 2004 and northern Florida in 2008, stated that this palm (as B. capitata) is not naturalised in the region, but that it is widely planted along the coastal strip of southeastern North Carolina, eastern South Carolina, eastern Georgia and northern Florida, and that these garden plants often persist despite neglect and can appear naturalised in superficially semi-natural locations.[16][17][18] In 2018 the first instance of this palm (now identified as B. odorata) naturalising in this region was published, based on specimen vouchers collected in 2007 from young plants some distance from human habitation in Camden Co., in the far southeast corner of Georgia.[19]

By at least 2009 an anonymous source considered this palm naturalised in Florida and it was included in the USDA PLANTS database.[15] In 2010 this opinion was validated when the first instance of a naturalised palm was published, recording a 2005 collection of a specimen in the dunes of the Chinsegut Wildlife and Environmental Area in Hernando Co.,[20] a former farm and estate with some plantings of Butia palms.[21][22] Another instance of this palm naturalising was recorded in literature (no voucher) in 2013 in Silver River State Park, Marion Co..[15] As of 2018, the Atlas of Florida Plants shows voucher specimens (identified as B. capitata (with a caveat)) have been collected in the central and northern counties of Hernando, Volusia, Washington, Liberty, Gadsden, Leon and Wakulla.[23]

Uses

As an ornamental

Butia odorata is frequently grown in Mediterranean Europe, the southern USA, Australia and southern Brazil as an ornamental garden plant.[3]

It is notable as one of the hardiest feather palms, sometimes tolerating brief drops in temperature down to about −10 °C at night; it is often cultivated in subtropical climates. It is (was) also often marketed as a hardy palm for exotic-looking gardens in temperate climates. In the United States, B. odorata is grown along the West Coast from San Diego to Seattle, and along the East Coast from Florida to Virginia Beach.

In the Netherlands it is advised to plant the palms in full sunlight. Larger specimens are said to take -10 to -12°C, but should be protected at -5°C, for example by wrapping heating strips around the trunk. It should be protected from excess rain during the winter, for example with a small, open tent. The substrate should be very porous so that water drains away from the roots quickly. In the summer this palm demands lots of water and should be watered regularly. It is possible to harvest fruit in the Netherlands.[24]

As food

It is cultivated as a fruit tree in Brazil and Uruguay, and especially the larger-fruited, semi-domesticated, pulposa-type plants are reasonably common in local orchards.[3]

In the type most often grown in Florida, the USA, the ripe fruit are about the size of large cherry, and yellowish/orange in colour, but can also include a blush towards the tip. The taste is a mixture of pineapple, apricot, and vanilla. Taste can vary depending on soil conditions, and the tastes of apple, pineapple, and banana together is also common. It is tart and sweet at the same time, with a flesh similar to a loquat, but slightly more fibrous.

Chemistry

The triterpenes cylindrin and lupeol methyl ether can be isolated from Butia odorata leaf epicuticular waxes.[25]

Conservation

Noblick in 1996 notes that the population he visited growing in a cattle pasture that had once been restinga was unhealthy as there was no recruitment (growth of new individuals). Rejuvenation of the population was hindered by fires and cattle grazing. Noblick also notes that much of its former habitat was being converted to rice fields.[8]

As of 2018 the conservation status has not been evaluated by the Centro Nacional de Conservação da Flora in Brazil.[8]

As of 2017, like all four species of Butia native to Uruguay, it is protected by law. Adult palms may not be felled or moved without government permission.

Gallery

Ripe fruit of Butia odorata palm growing in Ocean Isle Beach.

Ripe fruit of Butia odorata palm growing in Ocean Isle Beach. Butia odorata palm growing in Ocean Isle Beach, bearing both ripe and unripe fruit.

Butia odorata palm growing in Ocean Isle Beach, bearing both ripe and unripe fruit.- Fruit collected from a tree in Sertão Santana, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

A grove near Laguna Negra, Palmares de Castillos, Rocha Department, Uruguay.

A grove near Laguna Negra, Palmares de Castillos, Rocha Department, Uruguay. A thick grove of old trees at Palmar de tiburcio, Camino del Indio, Rocha, Uruguay.

A thick grove of old trees at Palmar de tiburcio, Camino del Indio, Rocha, Uruguay._(20692838501).jpg) Comparison of fruit by João Barbosa Rodrigues in 1901. B. odorata is 'B' (as Cocos pulposa) & 'C' (as C. odorata) -note the somewhat flatter fruit, which is much larger in the cultivated pulposa race. Butia yatay is 'A', B. eriospatha is 'D', and Syagrus coronata is 'E'.

Comparison of fruit by João Barbosa Rodrigues in 1901. B. odorata is 'B' (as Cocos pulposa) & 'C' (as C. odorata) -note the somewhat flatter fruit, which is much larger in the cultivated pulposa race. Butia yatay is 'A', B. eriospatha is 'D', and Syagrus coronata is 'E'.

References

- ↑ Govaerts, R. (2018). "World Checklist of Selected Plant Families". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Butia odorata". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Soares, Kelen Pureza (2015). "Le genre Butia". Principes (in French). 1: 12–57. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- 1 2 Wunderlin, R. P.; Hansen, B. F.; Franck, A. R.; Essig, F. B. (16 September 2018). "Butia capitata - Species Page". Atlas of Florida Plants. Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

Recent taxonomy suggests B. odorata is the species naturalized in Florida, which has globose fruits, small midrib bundles completely encircling the fibrous cylinder, and does not have raphide-containing idioblasts in the foliar margin, unlike B. capitata (Sant’Anna-Santos et. al 2015)

- ↑ Kembrey, Nigel (9 February 2013). "Buita nomenclature -new names". Hardy Tropicals UK. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Noblick, Larry R. (January 2014). "Butia: What we think we know about the genus". The Palm Journal - Journal of oil palm research. 208: 5–23. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bauermann, Soraia Girardi; Evaldt, Andréia Cardoso Pacheco; Zanchin, Janaína Rosana; de Loreto Bordignon, Sergio Augusto (June 2010). "Diferenciação polínica de Butia, Euterpe, Geonoma, Syagrus e Thritrinax e implicações paleoecológicas de Arecaceae para o Rio Grande do Sul". Iheringia - Série Botânica (in Portuguese). 65 (1): 35–46. ISSN 0073-4705. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Heiden, G.; Ellert-Pereira, P.E.; Eslabão, M.P. (2015). "Brazilian Flora Checklist - Butia odorara (Barb.Rodr.) Noblick". Butia in Lista de Espécies da Flora do Brasil, Flora do Brasil 2020 under construction (in Portuguese). Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ↑ von Martius, Karl Friedrich Philipp (1826). Historia Naturalis Palmarum - opus tripartium (in Latin). 2. Leipzig: T. O. Weigel. p. 114–115. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.506.

- ↑ Glassman, Sidney Fredrick (1970). "A conspectus of the palm genus Butia Becc". Fieldiana. 32 (10): 143–145. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.2384. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ Glassman, Sidney Fredrick (1979). "Re-evaluation of the Genus Butia With a Description of a New Species" (PDF). Principes. 23: 70–71. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ "Butyagrus nabonnandii". Palms. Palm & Cycad Societies of Australia. Archived from the original on 2013-05-19. Retrieved 2012-11-14.

- 1 2 "Flora del Conosur" (in Spanish). Instituto de Botánica Darwinion. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ↑ Zona, Scott (2000). "Syagrus romanzoffiana in Flora of North America @ efloras.org". Flora of North America. 22. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780195137293.

- 1 2 3 4 "Plants Profile for Butia capitata (South American jelly palm)". PLANTS Database. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Weakley, Alan S. (17 March 2004). Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 (PDF) (Report). University of North Carolina Herbarium. p. 612. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Weakley, Alan S. (10 June 2005). Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 10 June 2005 (PDF) (Report). University of North Carolina Herbarium. Retrieved 19 September 2018. Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004

- ↑ Weakley, Alan S. (7 April 2008). Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, Georgia, northern Florida, and surrounding areas, Working Draft of 7 April 2008 (PDF) (Report). University of North Carolina Herbarium. p. 645. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Zomlefer, Wendy B.; Richard Carter, J.; Allison, James R.; Wilson Baker, W.; Giannasi, David E.; Hughes, Steven C.; Lance, Ron W.; Lowe, Phillip D.; Lynch, Patrick S.; Miller, Jennifer T.; Patrick, Thomas S.; Prostko, Eric; Sewell, Sabrina Y.S.; Weakley, Alan S. (May 2018). "Additions to the Flora of Georgia Vouchered at the University of Georgia (GA) and Valdosta State University (VSC) Herbaria". Castanea. 83 (1): 124–139. doi:10.2179/17-151.

- ↑ Wunderlin, Richard P.; Hansen, Bruce F.; Franck, Alan R.; Bradley, Keith A.; Kunzer, John M. (2010). "Plants new to Florida". Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 4 (1): 350. doi:10.13140/2.1.1544.2560. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "Trail Tuesday: Chinsegut Wildlife and Environmental Area". visitflorida.com. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ "Chinsegut Wildlife and Environmental Area". myfwc.com. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ Atlas of Florida Plants http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=4222

- ↑ Wagelaar, Edwin (31 December 2017). "Het geslacht Butia". Palmexotica (in Dutch). Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Triterpene methyl ethers from palmae epicuticular waxes. S. García, H. Heinzen, C. Hubbuch, R. Martínez, X. de Vries and P. Moyna, Phytochemistry, August 1995, Volume 39, Issue 6, Pages 1381–1382, doi:10.1016/0031-9422(95)00173-5