Gray code

The reflected binary code (RBC), also known just as reflected binary (RB) or Gray code after Frank Gray, is an ordering of the binary numeral system such that two successive values differ in only one bit (binary digit). The reflected binary code was originally designed to prevent spurious output from electromechanical switches. Today, Gray codes are widely used to facilitate error correction in digital communications such as digital terrestrial television and some cable TV systems.

| Lucal code[1][2][3] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray code | |||||

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Name

Bell Labs researcher Frank Gray introduced the term reflected binary code in his 1947 patent application, remarking that the code had "as yet no recognized name".[4] He derived the name from the fact that it "may be built up from the conventional binary code by a sort of reflection process".

The code was later named after Gray by others who used it. Two different 1953 patent applications use "Gray code" as an alternative name for the "reflected binary code";[5][6] one of those also lists "minimum error code" and "cyclic permutation code" among the names.[6] A 1954 patent application refers to "the Bell Telephone Gray code".[7] Other names include "cyclic binary code" and "cyclic progression code".[8][9]

Motivation

Many devices indicate position by closing and opening switches. If that device uses natural binary codes, positions 3 and 4 are next to each other but all three bits of the binary representation differ:

| Decimal | Binary |

|---|---|

| ... | ... |

| 3 | 011 |

| 4 | 100 |

| ... | ... |

The problem with natural binary codes is that physical switches are not ideal: it is very unlikely that physical switches will change states exactly in synchrony. In the transition between the two states shown above, all three switches change state. In the brief period while all are changing, the switches will read some spurious position. Even without keybounce, the transition might look like 011 — 001 — 101 — 100. When the switches appear to be in position 001, the observer cannot tell if that is the "real" position 001, or a transitional state between two other positions. If the output feeds into a sequential system, possibly via combinational logic, then the sequential system may store a false value.

The reflected binary code solves this problem by changing only one switch at a time, so there is never any ambiguity of position:

| Decimal | Binary | Gray |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0000 | 0000 |

| 1 | 0001 | 0001 |

| 2 | 0010 | 0011 |

| 3 | 0011 | 0010 |

| 4 | 0100 | 0110 |

| 5 | 0101 | 0111 |

| 6 | 0110 | 0101 |

| 7 | 0111 | 0100 |

| 8 | 1000 | 1100 |

| 9 | 1001 | 1101 |

| 10 | 1010 | 1111 |

| 11 | 1011 | 1110 |

| 12 | 1100 | 1010 |

| 13 | 1101 | 1011 |

| 14 | 1110 | 1001 |

| 15 | 1111 | 1000 |

The Gray code for decimal 15 rolls over to decimal 0 with only one switch change. This is called the "cyclic" property of a Gray code. In the standard Gray coding the least significant bit follows a repetitive pattern of 2 on, 2 off ( … 11001100 … ); the next digit a pattern of 4 on, 4 off; and so forth.

More formally, a Gray code is a code assigning to each of a contiguous set of integers, or to each member of a circular list, a word of symbols such that no two code words are identical and each two adjacent code words differ by exactly one symbol. These codes are also known as single-distance codes, reflecting the Hamming distance of 1 between adjacent codes. In principle, there can be more than one such code for a given word length, but the term Gray code was first applied to a particular binary code for non-negative integers, the binary-reflected Gray code, or BRGC, the four-bit version of which is shown above.

History and practical application

Reflected binary codes were applied to mathematical puzzles before they became known to engineers. Martin Gardner wrote a popular account of the Gray code in his August 1972 Mathematical Games column in Scientific American. The French engineer Émile Baudot used Gray codes in telegraphy in 1878.[10] He received the French Legion of Honor medal for his work. The Gray code is sometimes attributed, incorrectly,[11] to Elisha Gray.[12][13]

Frank Gray, who became famous for inventing the signaling method that came to be used for compatible color television, invented a method to convert analog signals to reflected binary code groups using vacuum tube-based apparatus. The method and apparatus were patented in 1953 and the name of Gray stuck to the codes. The "PCM tube" apparatus that Gray patented was made by Raymond W. Sears of Bell Labs, working with Gray and William M. Goodall, who credited Gray for the idea of the reflected binary code.[14]

Gray was most interested in using the codes to minimize errors in converting analog signals to digital; his codes are still used today for this purpose.

Position encoders

.svg.png)

Gray codes are used in position encoders (linear encoders and rotary encoders), in preference to straightforward binary encoding. This avoids the possibility that, when several bits change in the binary representation of an angle, a misread will result from some of the bits changing before others. Originally, the code pattern was electrically conductive, supported (in a rotary encoder) by an insulating disk. Each track had its own stationary metal spring contact; one more contact made the connection to the pattern. That common contact was connected by the pattern to whichever of the track contacts were resting on the conductive pattern. However, sliding contacts wear out and need maintenance, so non-contact detectors, such as optical or magnetic sensors, are often used instead.

Regardless of the care in aligning the contacts, and accuracy of the pattern, a natural-binary code would have errors at specific disk positions, because it is impossible to make all bits change at exactly the same time as the disk rotates. The same is true of an optical encoder; transitions between opaque and transparent cannot be made to happen simultaneously for certain exact positions. Rotary encoders benefit from the cyclic nature of Gray codes, because consecutive positions of the sequence differ by only one bit. This means that, for a transition from state A to state B, timing mismatches can only affect when the A → B transition occurs, rather than inserting one or more (up to N − 1 for an N-bit codeword) false intermediate states, as would occur if a standard binary code were used.

Mathematical puzzles

The binary-reflected Gray code can serve as a solution guide for the Towers of Hanoi problem, as well as the classical Chinese rings puzzle, a sequential mechanical puzzle mechanism.[11] It also forms a Hamiltonian cycle on a hypercube, where each bit is seen as one dimension.

Genetic algorithms

Due to the Hamming distance properties of Gray codes, they are sometimes used in genetic algorithms. They are very useful in this field, since mutations in the code allow for mostly incremental changes, but occasionally a single bit-change can cause a big leap and lead to new properties.

Boolean circuit minimization

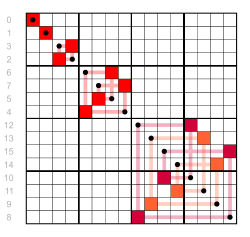

Gray codes are also used in labelling the axes of Karnaugh maps[15][16] as well as in Händler circle graphs,[17][18][19][20] both graphical methods for logic circuit minimization.

Error correction

In modern digital communications, Gray codes play an important role in error correction. For example, in a digital modulation scheme such as QAM where data is typically transmitted in symbols of 4 bits or more, the signal's constellation diagram is arranged so that the bit patterns conveyed by adjacent constellation points differ by only one bit. By combining this with forward error correction capable of correcting single-bit errors, it is possible for a receiver to correct any transmission errors that cause a constellation point to deviate into the area of an adjacent point. This makes the transmission system less susceptible to noise.

Communication between clock domains

Digital logic designers use Gray codes extensively for passing multi-bit count information between synchronous logic that operates at different clock frequencies. The logic is considered operating in different "clock domains". It is fundamental to the design of large chips that operate with many different clocking frequencies.

Cycling through states with minimal effort

If a system has to cycle through all possible combinations of on-off states of some set of controls, and the changes of the controls require non-trivial expense (e.g. time, wear, human work), a Gray code minimizes the number of setting changes to just one change for each combination of states. An example would be testing a piping system for all combinations of settings of its manually operated valves.

Gray code counters and arithmetic

A typical use of Gray code counters is building a FIFO (first-in, first-out) data buffer that has read and write ports that exist in different clock domains. The input and output counters inside such a dual-port FIFO are often stored using Gray code to prevent invalid transient states from being captured when the count crosses clock domains.[21] The updated read and write pointers need to be passed between clock domains when they change, to be able to track FIFO empty and full status in each domain. Each bit of the pointers is sampled non-deterministically for this clock domain transfer. So for each bit, either the old value or the new value is propagated. Therefore, if more than one bit in the multi-bit pointer is changing at the sampling point, a "wrong" binary value (neither new nor old) can be propagated. By guaranteeing only one bit can be changing, Gray codes guarantee that the only possible sampled values are the new or old multi-bit value. Typically Gray codes of power-of-two length are used.

Sometimes digital buses in electronic systems are used to convey quantities that can only increase or decrease by one at a time, for example the output of an event counter which is being passed between clock domains or to a digital-to-analog converter. The advantage of Gray codes in these applications is that differences in the propagation delays of the many wires that represent the bits of the code cannot cause the received value to go through states that are out of the Gray code sequence. This is similar to the advantage of Gray codes in the construction of mechanical encoders, however the source of the Gray code is an electronic counter in this case. The counter itself must count in Gray code, or if the counter runs in binary then the output value from the counter must be reclocked after it has been converted to Gray code, because when a value is converted from binary to Gray code, it is possible that differences in the arrival times of the binary data bits into the binary-to-Gray conversion circuit will mean that the code could go briefly through states that are wildly out of sequence. Adding a clocked register after the circuit that converts the count value to Gray code may introduce a clock cycle of latency, so counting directly in Gray code may be advantageous. A Gray code counter was patented in 1962 US3020481, and there have been many others since. In recent times a Gray code counter can be implemented as a state machine in Verilog. In order to produce the next count value, it is necessary to have some combinational logic that will increment the current count value that is stored in Gray code. Probably the most obvious way to increment a Gray code number is to convert it into ordinary binary code, add one to it with a standard binary adder, and then convert the result back to Gray code. This approach was discussed in a paper in 1996[22] and then subsequently patented by someone else in 1998 US5754614. Other methods of counting in Gray code are discussed in a report by Robert W. Doran, including taking the output from the first latches of the master-slave flip flops in a binary ripple counter.[23]

Perhaps the most common electronic counter with the "only one bit changes at a time" property is the Johnson counter.

Gray code addressing

As the execution of program code typically causes an instruction memory access pattern of locally consecutive addresses, bus encodings using Gray code addressing instead of binary addressing can reduce the number of state changes of the address bits significantly, thereby reducing the CPU power consumption in some low-power designs.[24][25]

Constructing an n-bit Gray code

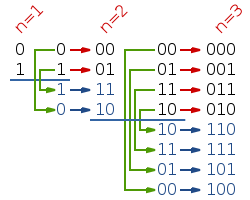

The binary-reflected Gray code list for n bits can be generated recursively from the list for n − 1 bits by reflecting the list (i.e. listing the entries in reverse order), prefixing the entries in the original list with a binary 0, prefixing the entries in the reflected list with a binary 1, and then concatenating the original list with the reversed list.[11] For example, generating the n = 3 list from the n = 2 list:

| 2-bit list: | 00, 01, 11, 10 | |

| Reflected: | 10, 11, 01, 00 | |

| Prefix old entries with 0: | 000, 001, 011, 010, | |

| Prefix new entries with 1: | 110, 111, 101, 100 | |

| Concatenated: | 000, 001, 011, 010, | 110, 111, 101, 100 |

The one-bit Gray code is G1 = (0, 1). This can be thought of as built recursively as above from a zero-bit Gray code G0 = ( Λ ) consisting of a single entry of zero length. This iterative process of generating Gn+1 from Gn makes the following properties of the standard reflecting code clear:

- Gn is a permutation of the numbers 0, ..., 2n−1. (Each number appears exactly once in the list.)

- Gn is embedded as the first half of Gn+1.

- Therefore, the coding is stable, in the sense that once a binary number appears in Gn it appears in the same position in all longer lists; so it makes sense to talk about the reflective Gray code value of a number: G(m) = the m-th reflecting Gray code, counting from 0.

- Each entry in Gn differs by only one bit from the previous entry. (The Hamming distance is 1.)

- The last entry in Gn differs by only one bit from the first entry. (The code is cyclic.)

These characteristics suggest a simple and fast method of translating a binary value into the corresponding Gray code. Each bit is inverted if the next higher bit of the input value is set to one. This can be performed in parallel by a bit-shift and exclusive-or operation if they are available: the nth Gray code is obtained by computing

A similar method can be used to perform the reverse translation, but the computation of each bit depends on the computed value of the next higher bit so it cannot be performed in parallel. Assuming is the th Gray-coded bit ( being the most significant bit), and is the th binary-coded bit ( being the most-significant bit), the reverse translation can be given recursively: , and . Alternatively, decoding a Gray code into a binary number can be described as a prefix sum of the bits in the Gray code, where each individual summation operation in the prefix sum is performed modulo two.

To construct the binary-reflected Gray code iteratively, at step 0 start with the , and at step find the bit position of the least significant 1 in the binary representation of and flip the bit at that position in the previous code to get the next code . The bit positions start 0, 1, 0, 2, 0, 1, 0, 3, ... (sequence A007814 in the OEIS). See find first set for efficient algorithms to compute these values.

Converting to and from Gray code

The following functions in C convert between binary numbers and their associated Gray codes. While it may seem that Gray-to-binary conversion requires each bit to be handled one at a time, faster algorithms exist.[26]

/*

* This function converts an unsigned binary

* number to reflected binary Gray code.

*

* The operator >> is shift right. The operator ^ is exclusive or.

*/

unsigned int BinaryToGray(unsigned int num)

{

return num ^ (num >> 1);

}

/*

* This function converts a reflected binary

* Gray code number to a binary number.

* Each Gray code bit is exclusive-ored with all

* more significant bits.

*/

unsigned int GrayToBinary(unsigned int num)

{

unsigned int mask = num >> 1;

while (mask != 0)

{

num = num ^ mask;

mask = mask >> 1;

}

return num;

}

/*

* A more efficient version for Gray codes 32 bits or fewer

* through the use of SWAR (SIMD within a register) techniques.

* It implements a parallel prefix XOR function. The assignment

* statements can be in any order.

*

* This function can be adapted for longer Gray codes by adding steps.

* A 4-bit variant changes a binary number (abcd)2 to (abcd)2 ^ (00ab)2,

* then to (abcd)2 ^ (00ab)2 ^ (0abc)2 ^ (000a)2.

*/

unsigned int GrayToBinary32(unsigned int num)

{

num = num ^ (num >> 16);

num = num ^ (num >> 8);

num = num ^ (num >> 4);

num = num ^ (num >> 2);

num = num ^ (num >> 1);

return num;

}

Special types of Gray codes

In practice, "Gray code" almost always refers to a binary-reflected Gray code (BRGC). However, mathematicians have discovered other kinds of Gray codes. Like BRGCs, each consists of a lists of words, where each word differs from the next in only one digit (each word has a Hamming distance of 1 from the next word).

n-ary Gray code

|

There are many specialized types of Gray codes other than the binary-reflected Gray code. One such type of Gray code is the n-ary Gray code, also known as a non-Boolean Gray code. As the name implies, this type of Gray code uses non-Boolean values in its encodings.

For example, a 3-ary (ternary) Gray code would use the values {0, 1, 2}. The (n, k)-Gray code is the n-ary Gray code with k digits.[27] The sequence of elements in the (3, 2)-Gray code is: {00, 01, 02, 12, 11, 10, 20, 21, 22}. The (n, k)-Gray code may be constructed recursively, as the BRGC, or may be constructed iteratively. An algorithm to iteratively generate the (N, k)-Gray code is presented (in C):

// inputs: base, digits, value

// output: Gray

// Convert a value to a Gray code with the given base and digits.

// Iterating through a sequence of values would result in a sequence

// of Gray codes in which only one digit changes at a time.

void toGray(unsigned base, unsigned digits, unsigned value, unsigned gray[digits])

{

unsigned baseN[digits]; // Stores the ordinary base-N number, one digit per entry

unsigned i; // The loop variable

// Put the normal baseN number into the baseN array. For base 10, 109

// would be stored as [9,0,1]

for (i = 0; i < digits; i++) {

baseN[i] = value % base;

value = value / base;

}

// Convert the normal baseN number into the Gray code equivalent. Note that

// the loop starts at the most significant digit and goes down.

unsigned shift = 0;

while (i--) {

// The Gray digit gets shifted down by the sum of the higher

// digits.

gray[i] = (baseN[i] + shift) % base;

shift = shift + base - gray[i]; // Subtract from base so shift is positive

}

}

// EXAMPLES

// input: value = 1899, base = 10, digits = 4

// output: baseN[] = [9,9,8,1], gray[] = [0,1,7,1]

// input: value = 1900, base = 10, digits = 4

// output: baseN[] = [0,0,9,1], gray[] = [0,1,8,1]

There are other Gray code algorithms for (n,k)-Gray codes. The (n,k)-Gray code produced by the above algorithm is always cyclical; some algorithms, such as that by Guan,[27] lack this property when k is odd. On the other hand, while only one digit at a time changes with this method, it can change by wrapping (looping from n − 1 to 0). In Guan's algorithm, the count alternately rises and falls, so that the numeric difference between two Gray code digits is always one.

Gray codes are not uniquely defined, because a permutation of the columns of such a code is a Gray code too. The above procedure produces a code in which the lower the significance of a digit, the more often it changes, making it similar to normal counting methods.

See also Skew binary number system, a variant ternary number system where at most 2 digits change on each increment, as each increment can be done with at most one digit carry operation.

Balanced Gray code

Although the binary reflected Gray code is useful in many scenarios, it is not optimal in certain cases because of a lack of "uniformity".[28] In balanced Gray codes, the number of changes in different coordinate positions are as close as possible. To make this more precise, let G be an R-ary complete Gray cycle having transition sequence ; the transition counts (spectrum) of G are the collection of integers defined by

A Gray code is uniform or uniformly balanced if its transition counts are all equal, in which case we have for all k. Clearly, when , such codes exist only if n is a power of 2. Otherwise, if n does not divide evenly, it is possible to construct well-balanced codes where every transition count is either or . Gray codes can also be exponentially balanced if all of their transition counts are adjacent powers of two, and such codes exist for every power of two.[29]

For example, a balanced 4-bit Gray code has 16 transitions, which can be evenly distributed among all four positions (four transitions per position), making it uniformly balanced:[28]

0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1

whereas a balanced 5-bit Gray code has a total of 32 transitions, which cannot be evenly distributed among the positions. In this example, four positions have six transitions each, and one has eight:[28]

1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1

We will now show a construction[30] and implementation[31] for well-balanced binary Gray codes which allows us to generate an n-digit balanced Gray code for every n. The main principle is to inductively construct an (n + 2)-digit Gray code given an n-digit Gray code G in such a way that the balanced property is preserved. To do this, we consider partitions of into an even number L of non-empty blocks of the form

where , and (mod ). This partition induces an -digit Gray code given by

If we define the transition multiplicities to be the number of times the digit in position i changes between consecutive blocks in a partition, then for the (n + 2)-digit Gray code induced by this partition the transition spectrum is

The delicate part of this construction is to find an adequate partitioning of a balanced n-digit Gray code such that the code induced by it remains balanced, but for this only the transition multiplicities matter; joining two consecutive blocks over a digit transition and splitting another block at another digit transition produces a different Gray code with exactly the same transition spectrum , so one may for example[29] designate the first transitions at digit as those that fall between two blocks. Uniform codes can be found when and , and this construction can be extended to the R-ary case as well.[30]

Monotonic Gray codes

Monotonic codes are useful in the theory of interconnection networks, especially for minimizing dilation for linear arrays of processors.[32] If we define the weight of a binary string to be the number of 1s in the string, then although we clearly cannot have a Gray code with strictly increasing weight, we may want to approximate this by having the code run through two adjacent weights before reaching the next one.

We can formalize the concept of monotone Gray codes as follows: consider the partition of the hypercube into levels of vertices that have equal weight, i.e.

for . These levels satisfy . Let be the subgraph of induced by , and let be the edges in . A monotonic Gray code is then a Hamiltonian path in such that whenever comes before in the path, then .

An elegant construction of monotonic n-digit Gray codes for any n is based on the idea of recursively building subpaths of length having edges in .[32] We define , whenever or , and

otherwise. Here, is a suitably defined permutation and refers to the path P with its coordinates permuted by . These paths give rise to two monotonic n-digit Gray codes and given by

The choice of which ensures that these codes are indeed Gray codes turns out to be . The first few values of are shown in the table below.

| j = 0 | j = 1 | j = 2 | j = 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1 | 0, 1 | |||

| n = 2 | 00, 01 | 10, 11 | ||

| n = 3 | 000, 001 | 100, 110, 010, 011 | 101, 111 | |

| n = 4 | 0000, 0001 | 1000, 1100, 0100, 0110, 0010, 0011 | 1010, 1011, 1001, 1101, 0101, 0111 | 1110, 1111 |

These monotonic Gray codes can be efficiently implemented in such a way that each subsequent element can be generated in O(n) time. The algorithm is most easily described using coroutines.

Monotonic codes have an interesting connection to the Lovász conjecture, which states that every connected vertex-transitive graph contains a Hamiltonian path. The "middle-level" subgraph is vertex-transitive (that is, its automorphism group is transitive, so that each vertex has the same "local environment"" and cannot be differentiated from the others, since we can relabel the coordinates as well as the binary digits to obtain an automorphism) and the problem of finding a Hamiltonian path in this subgraph is called the "middle-levels problem", which can provide insights into the more general conjecture. The question has been answered affirmatively for , and the preceding construction for monotonic codes ensures a Hamiltonian path of length at least 0.839N where N is the number of vertices in the middle-level subgraph.[33]

Beckett–Gray code

Another type of Gray code, the Beckett–Gray code, is named for Irish playwright Samuel Beckett, who was interested in symmetry. His play "Quad" features four actors and is divided into sixteen time periods. Each period ends with one of the four actors entering or leaving the stage. The play begins with an empty stage, and Beckett wanted each subset of actors to appear on stage exactly once.[34] Clearly the set of actors currently on stage can be represented by a 4-bit binary Gray code. Beckett, however, placed an additional restriction on the script: he wished the actors to enter and exit so that the actor who had been on stage the longest would always be the one to exit. The actors could then be represented by a first in, first out queue, so that (of the actors onstage) the actor being dequeued is always the one who was enqueued first.[34] Beckett was unable to find a Beckett–Gray code for his play, and indeed, an exhaustive listing of all possible sequences reveals that no such code exists for n = 4. It is known today that such codes do exist for n = 2, 5, 6, 7, and 8, and do not exist for n = 3 or 4. An example of an 8-bit Beckett–Gray code can be found in Donald Knuth's Art of Computer Programming.[11] According to Sawada and Wong, the search space for n = 6 can be explored in 15 hours, and more than 9,500 solutions for the case n = 7 have been found.[35]

Snake-in-the-box codes

Snake-in-the-box codes, or snakes, are the sequences of nodes of induced paths in an n-dimensional hypercube graph, and coil-in-the-box codes, or coils, are the sequences of nodes of induced cycles in a hypercube. Viewed as Gray codes, these sequences have the property of being able to detect any single-bit coding error. Codes of this type were first described by William H. Kautz in the late 1950s;[36] since then, there has been much research on finding the code with the largest possible number of codewords for a given hypercube dimension.

Single-track Gray code

Yet another kind of Gray code is the single-track Gray code (STGC) developed by Norman B. Spedding[37][38] and refined by Hiltgen, Paterson and Brandestini in "Single-track Gray codes" (1996).[39][40] The STGC is a cyclical list of P unique binary encodings of length n such that two consecutive words differ in exactly one position, and when the list is examined as a P × n matrix, each column is a cyclic shift of the first column.[41]

The name comes from their use with rotary encoders, where a number of tracks are being sensed by contacts, resulting for each in an output of 0 or 1. To reduce noise due to different contacts not switching at exactly the same moment in time, one preferably sets up the tracks so that the data output by the contacts are in Gray code. To get high angular accuracy, one needs lots of contacts; in order to achieve at least 1 degree accuracy, one needs at least 360 distinct positions per revolution, which requires a minimum of 9 bits of data, and thus the same number of contacts.

If all contacts are placed at the same angular position, then 9 tracks are needed to get a standard BRGC with at least 1 degree accuracy. However, if the manufacturer moves a contact to a different angular position (but at the same distance from the center shaft), then the corresponding "ring pattern" needs to be rotated the same angle to give the same output. If the most significant bit (the inner ring in Figure 1) is rotated enough, it exactly matches the next ring out. Since both rings are then identical, the inner ring can be cut out, and the sensor for that ring moved to the remaining, identical ring (but offset at that angle from the other sensor on that ring). Those two sensors on a single ring make a quadrature encoder. That reduces the number of tracks for a "1 degree resolution" angular encoder to 8 tracks. Reducing the number of tracks still further can't be done with BRGC.

For many years, Torsten Sillke[42] and other mathematicians believed that it was impossible to encode position on a single track such that consecutive positions differed at only a single sensor, except for the 2-sensor, 1-track quadrature encoder. So for applications where 8 tracks were too bulky, people used single-track incremental encoders (quadrature encoders) or 2-track "quadrature encoder + reference notch" encoders.

Norman B. Spedding, however, registered a patent in 1994 with several examples showing that it was possible.[37] Although it is not possible to distinguish 2n positions with n sensors on a single track, it is possible to distinguish close to that many. For example, when n is itself a power of 2, n sensors can distinguish 2n − 2n positions.[43] Hiltgen and Paterson published a paper in 2001 exhibiting a single-track Gray code with exactly 360 angular positions, constructed using 9 sensors.[40] Since this number is larger than 28 = 256, more than 8 sensors are required by any code, although a BRGC could distinguish 512 positions with 9 sensors. An STGC for P = 30 and n = 5 is reproduced here:

| Angle | Code | Angle | Code | Angle | Code | Angle | Code | Angle | Code | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0° | 10000 | 72° | 01000 | 144° | 00100 | 216° | 00010 | 288° | 00001 | ||||

| 12° | 10100 | 84° | 01010 | 156° | 00101 | 228° | 10010 | 300° | 01001 | ||||

| 24° | 11100 | 96° | 01110 | 168° | 00111 | 240° | 10011 | 312° | 11001 | ||||

| 36° | 11110 | 108° | 01111 | 180° | 10111 | 252° | 11011 | 324° | 11101 | ||||

| 48° | 11010 | 120° | 01101 | 192° | 10110 | 264° | 01011 | 336° | 10101 | ||||

| 60° | 11000 | 132° | 01100 | 204° | 00110 | 276° | 00011 | 348° | 10001 |

Each column is a cyclic shift of the first column, and from any row to the next row only one bit changes.[44] The single-track nature (like a code chain) is useful in the fabrication of these wheels (compared to BRGC), as only one track is needed, thus reducing their cost and size. The Gray code nature is useful (compared to chain codes, also called De Bruijn sequences), as only one sensor will change at any one time, so the uncertainty during a transition between two discrete states will only be plus or minus one unit of angular measurement the device is capable of resolving.[45]

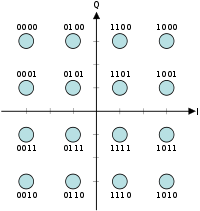

Two-dimensional Gray code

Two-dimensional Gray codes are used in communication to minimize the number of bit errors in quadrature amplitude modulation adjacent points in the constellation. In a typical encoding the horizontal and vertical adjacent constellation points differ by a single bit, and diagonal adjacent points differ by 2 bits.[46]

Gray isometry

The bijective mapping { 0 ↔ 00, 1 ↔ 01, 2 ↔ 11, 3 ↔ 10 } establishes an isometry between the metric space over the finite field with the metric given by the Hamming distance and the metric space over the finite ring (the usual modulo arithmetic) with the metric given by the Lee distance. The mapping is suitably extended to an isometry of the Hamming spaces and . Its importance lies in establishing a correspondence between various "good" but not necessarily linear codes as Gray-map images in of ring-linear codes from .[47][48]

Related codes

There are a number of binary codes similar to Gray codes, including:

- Lucal code[1][3][2] aka Modified reflected binary code (MRB)[2][1]

- Varec code

- Datex code (aka Giannini code)[49]

- Gillham code

- Hoklas code[50][51][52]

The following binary-coded decimal (BCD) codes are Gray code variants as well:

- Gray-Excess code (aka Gray-Excess-3 code, Gray-3-Excess code, Reflex-Excess-3 code, Excess-Gray code,[51] 10-Excess-3-Gray code or Gray-Stibitz code)

- Glixon code[53][54][55][51]

- O'Brien codes[56][54][55][51]

- Petherick code[8][57][51]

- Tompkins codes[58][54][55][51]

- Kautz code[59][54][55]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Linear feedback shift register

- De Bruijn sequence

- Steinhaus–Johnson–Trotter algorithm, an algorithm that generates Gray codes for the factorial number system

References

- 1 2 3 Sellers, Jr., Frederick F.; Hsiao, Mu-Yue; Bearnson, Leroy W. (November 1968). Error Detecting Logic for Digital Computers (1st ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 152–164. LCCN 68-16491. OCLC 439460.

- 1 2 3 Lucal, Harold M. (December 1959). "Arithmetic Operations for Digital Computers Using a Modified Reflected Binary". IEEE Transactions on Electronic Computers. EC-8 (4): 444–458. doi:10.1109/TEC.1959.5222057. ISSN 0367-9950.

- 1 2 Richards, Richard Kohler (1955). Arithmetic Operations in Digital Computers (5 ed.). New York, USA: D. Van Nostrand Co., Inc.

- ↑ Gray, Frank (1953-03-17), Pulse code communication (NB. U.S. Patent 2,632,058 filed November 1947.)

- ↑ Breckman, Jack (1956-01-31), Encoding Circuit (NB. U.S. Patent 2,733,432 filed December 1953.)

- 1 2 Ragland, Earl Albert; Schultheis, Jr., Harry B. (1958-02-11), Direction-Sensitive Binary Code Position Control System (NB. U.S. Patent 2,823,345 filed October 1953).)

- ↑ Domeshek, Sol; Reiner, Stewart (1958-06-24), Automatic Rectification System (NB. U.S. Patent 2,839,974 filed January 1954.)

- 1 2 3 Petherick, Edward J. (1953). "A Cyclic Progressive Binary-coded-decimal System of Representing Numbers" (Technical Note MS15). Farnborough, UK: Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE).

- ↑ Winder, C. Farrell (October 1959). "Shaft Angle Encoders Afford High Accuracy" (PDF). Electronic Industries. Chilton Company. 18 (10): 76–80. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

[…] The type of code wheel most popular in optical encoders contains a cyclic binary code pattern designed to give a cyclic sequence of "on-off" outputs. The cyclic binary code is also known as the cyclic progression code, the reflected binary code, and the Gray code. This code was originated by G. R. Stibitz, of Bell Telephone Laboratories, and was first proposed for pulse code modulation systems by Frank Gray, also of BTL. Thus the name Gray code. The Gray or cyclic code is used mainly to eliminate the possibility of errors at code transition which could result in gross ambiguities. […]

- ↑ Pickover, Clifford A. (2009). The Math Book: From Pythagoras to the 57th Dimension, 250 Milestones in the History of Mathematics. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 392. ISBN 9781402757969.

- 1 2 3 4 Knuth, Donald Ervin (2004-10-15). "Generating all n-tuples". The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 4A: Enumeration and Backtracking. pre-fascicle 2a.

- ↑ Cattermole, Kenneth W. (1969). Principles of Pulse Code Modulation. New York, USA: American Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-19747-8.

- ↑ Edwards, Anthony William Fairbank (2004). Cogwheels of the Mind: The Story of Venn Diagrams. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 48, 50. ISBN 0-8018-7434-3.

- ↑ Goodall, William M. (January 1951). "Television by Pulse Code Modulation". Bell System Technical Journal. 30 (1): 33–49. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1951.tb01365.x. Retrieved 2017-10-29. (NB. Presented orally before the I.R.E. National Convention, New York City, March 1949.)

- ↑ Wakerly, John F. (1994). Digital Design: Principles & Practices. New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. pp. 222, 48–49. ISBN 0-13-211459-3. (NB. The two page sections taken together say that K-maps are labeled with Gray code. The first section says that they are labeled with a code that changes only one bit between entries and the second section says that such a code is called Gray code.)

- ↑ Brown, Frank Markham (2012) [2003, 1990]. Boolean Reasoning - The Logic of Boolean Equations (reissue of 2nd ed.). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-486-42785-0.

- ↑ Händler, Wolfgang (1958). Ein Minimisierungsverfahren zur Synthese von Schaltkreisen: Minimisierungsgraphen (Dissertation) (in German). Technische Hochschule Darmstadt. D 17. (NB. Although written by a German, the title contains an anglicism; the correct German term would be "Minimierung" instead of "Minimisierung".)

- ↑ Berger, Erich R.; Händler, Wolfgang (1967) [1962]. Steinbuch, Karl W.; Wagner, Siegfried W., eds. Taschenbuch der Nachrichtenverarbeitung (in German) (2 ed.). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag OHG. pp. 64, 1034–1035, 1036, 1038. LCCN 67-21079. Title No. 1036.

[…] Übersichtlich ist die Darstellung nach Händler, die sämtliche Punkte, numeriert nach dem Gray-Code […], auf dem Umfeld eines Kreises anordnet. Sie erfordert allerdings sehr viel Platz. […] [Händler's diagram, where all points, numbered according to the Gray code, are arranged on the circumference of a circle, is easily comprehensible. It needs, however, a lot of space.]

- ↑ "Informatik Sammlung Erlangen (ISER)" (in German). Erlangen, Germany: Friedrich-Alexander Universität. 2012-03-13. Archived from the original on 2017-05-16. Retrieved 2017-04-12. (NB. Shows a picture of a Händler circle graph.)

- ↑ "Informatik Sammlung Erlangen (ISER) - Impressum" (in German). Erlangen, Germany: Friedrich-Alexander Universität. 2012-03-13. Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2017-04-15. (NB. Shows a picture of a Händler circle graph.)

- ↑ Donohue, Ryan (2003). "Synchronization in Digital Logic Circuits" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-01-15. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- ↑ Mehta, Huzefa; Owens, Robert Michael; Irwin, Mary Jane "Janie" (1996-03-22). "Some issues in Gray code addressing". Proceedings of the 6th Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI (GLSVLSI 96). IEEE Computer Society: 178. doi:10.1109/GLSV.1996.497616. ISSN 1066-1395.

- ↑ Doran, Robert W. (March 2007). "The Gray Code" (PDF). CDMTCS Research Report Series. University of Auckland, New Zealand. CDMTCS-304. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ↑ Su, Ching-Long; Tsui, Chi-Ying; Despain, Alvin M. (1994). Low Power Architecture Design and Compilation Techniques for High-Performance Processors (PDF) (Report). Advanced Computer Architecture Laboratory. ACAL-TR-94-01.

- ↑ Guo, Hui; Parameswaran, Sri (April–June 2010). "Shifted Gray encoding to reduce instruction memory address bus switching for low-power embedded systems". Journal of Systems Architecture. 56 (4–6): 180–190. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2010.03.003.

- ↑ Dietz, Henry Gordon. "The Aggregate Magic Algorithms: Gray Code Conversion".

- 1 2 Guan, Dah-Jyh (1998). "Generalized Gray Codes with Applications". Proceedings of the National Scientic Council, Republic of China, Part A. 22: 841–848. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.119.1344.

- 1 2 3 Bhat, Girish S.; Savage, Carla Diane (1996). "Balanced Gray codes". Electronic Journal of Combinatorics. 3 (1): R25.

- 1 2 Suparta, I. Nengah (2005). "A simple proof for the existence of exponentially balanced Gray codes". Electronic Journal of Combinatorics. 12.

- 1 2 Flahive, Mary Elizabeth; Bose, Bella (2007). "Balancing cyclic R-ary Gray codes". Electronic Journal of Combinatorics. 14.

- ↑ Strackx, Raoul; Piessens, Frank (2016). "Ariadne: A Minimal Approach to State Continuity". Usenix Security. 25.

- 1 2 Savage, Carla Diane; Winkler, Peter (1995). "Monotone Gray codes and the middle levels problem". Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series A. 70 (2): 230–248. doi:10.1016/0097-3165(95)90091-8. ISSN 0097-3165.

- ↑ Savage, Carla Diane (1997). "Long cycles in the middle two levels of the Boolean lattice".

- 1 2 Goddyn, Luis (1999). "MATH 343 Applied Discrete Math Supplementary Materials" (PDF). Department of Mathematics, Simon Fraser University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-17.

- ↑ Sawada, Joseph "Joe"; Wong, Dennis Chi-Him (2007). "A Fast Algorithm to generate Beckett–Gray codes". Electronic Notes in Discrete Mathematics. 29: 571–577. doi:10.1016/j.endm.2007.07.091.

- ↑ Kautz, William H. (1958). "Unit-distance error-checking codes". IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers. 7: 177–180.

- 1 2 NZ 264738, Spedding, Norman Bruce, "A position encoder", published 1994-10-28

- ↑ Spedding, Norman Bruce. "The following is a copy of the provisional patent filed on behalf of Industrial Research Limited on 28 October 1994 - NZ Patent 264738" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

- ↑ Hiltgen, Alain P.; Paterson, Kenneth G.; Brandestini, Marco (September 1996). "Single-Track Gray Codes" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 42 (5): 1555–1561. doi:10.1109/18.532900. Zbl 857.94007.

- 1 2 Hiltgen, Alain P.; Paterson, Kenneth G. (September 2001). "Single-Track Circuit Codes" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 47 (6): 2587–2595. doi:10.1109/18.945274. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-01-15. Retrieved 2018-01-15. (NB. No mention of Spedding.)

- ↑ Etzion, Tuvi; Schwartz, Moshe (November 1999) [1998-05-17]. "The Structure of Single-Track Gray Codes" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. IT-45 (7): 2383–2396. doi:10.1109/18.796379. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-01-15. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- ↑ Sillke, Torsten (1997) [1993-03-01]. "Gray-Codes with few tracks (a question of Marco Brandestini)". Archived from the original on 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ↑ Etzion, Tuvi; Paterson, Kenneth G. (May 1996). "Near Optimal Single-Track Gray Codes" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. IT-42 (3): 779&ndash, 789. doi:10.1109/18.490544. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-30. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- ↑ Ruskey, Frank; Weston, Mark (2005-06-18). "A Survey of Venn Diagrams: Symmetric Diagrams". Electronic Journal of Combinatorics.

- ↑ Alciatore, David G.; Histand, Michael B. (1999). Mechatronics. McGraw–Hill Education – Europe. ISBN 978-0-07-131444-2.

- ↑ Krishna (2008-05-11). "Gray code for QAM". Archived from the original on 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ↑ Greferath, Marcus (2009). "An Introduction to Ring-Linear Coding Theory". In Sala, Massimiliano; Mora, Teo; Perret, Ludovic; Sakata, Shojiro; Traverso, Carlo. Gröbner Bases, Coding, and Cryptography. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 220. ISBN 978-3-540-93806-4.

- ↑ Solé, Patrick (2016-04-17). Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. "Kerdock and Preparata codes". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 1-4020-0609-8. Archived from the original on 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2017-10-29.

- ↑ Spaulding, Carl P. (1965-01-12) [1954-03-09]. "US Patent: Digital coding and translating system". Datex Corp. Patent US3165731A. Archived from the original on 2018-01-21. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ↑ Hoklas, Archibald (1989-09-06) [1988-04-29]. "DDR-Wirtschaftspatent DD 271 603 A1: Abtastvorrichtung zur digitalen Weg- oder Winkelmessung" (PDF) (in German). VEB Schiffselektronik Johannes Warnke, GDR: DEPATIS. WP H 03 M / 315 194 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-01-18. Retrieved 2018-01-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hoklas, Archibald (2005). "Gray code - Unit distance code". Archived from the original on 2018-01-15. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- ↑ Hoklas, Archibald (2005). "Gray-Kode - Einschrittiger Abtastkode" (in German). Archived from the original on 2018-01-15. Retrieved 2018-01-15.

- 1 2 Glixon, Harry Robert (March 1957). "Can You Take Advantage of the Cyclic Binary-Decimal Code?". Control Engineering. 4 (3): 87–91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Steinbuch, Karl W., ed. (1962). Written at Karlsruhe, Germany. Taschenbuch der Nachrichtenverarbeitung (in German) (1 ed.). Berlin / Göttingen / New York: Springer-Verlag OHG. pp. 71–74, 97, 761–764, 770, 1080–1081. LCCN 62-14511.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Steinbuch, Karl W.; Weber, Wolfgang; Heinemann, Traute, eds. (1974) [1967]. Taschenbuch der Informatik – Band II – Struktur und Programmierung von EDV-Systemen. Taschenbuch der Nachrichtenverarbeitung (in German). 2 (3 ed.). Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag. pp. 98–100. ISBN 3-540-06241-6. LCCN 73-80607.

- 1 2 3 O'Brien, Joseph A. (May 1956). "Cyclic Decimal Codes for Analogue to Digital Converters". Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, Part I: Communication and Electronics. 75 (2): 120–122. doi:10.1109/TCE.1956.6372498. ISSN 0097-2452.

- 1 2 Charnley, C. J.; Bidgood, R. E.; Boardman, G. E. T. (October 1965). "The Design of a Pneumatic Position Encoder" (PDF). IFAC Proceedings Volumes. The College of Aeronautics, Cranfield, Bedford, England. 2 (3): 75–88. doi:10.1016/S1474-6670(17)68955-9. Chapter 1.5. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

- 1 2 3 Tompkins, Howard E. (September 1956). "Unit-Distance Binary-Decimal Codes for Two-Track Commutation". IRE Transactions on Electronic Computers. EC-5 (3): 139. doi:10.1109/TEC.1956.5219934. ISSN 0367-9950.

- ↑ Kautz, William H. (1954). "Optimized Data Encoding for Digital Computers". Convention Record IRE (part 4): 47–57.

Further reading

- Black, Paul E. (2004-02-25). "Gray code". NIST.

- Press, William H.; Teukolsky, Saul A.; Vetterling, William T.; Flannery, Brian P. (2007). "Section 22.3. Gray Codes". Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.). New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8.

- Savage, Carla Diane (1997). "A Survey of Combinatorial Gray Codes". SIAM Review. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM). 39 (4): 605–629. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.39.1924. doi:10.1137/S0036144595295272. JSTOR 2132693.

- Wilf, Herbert S. (1989). "Chapters 1–3". Combinatorial algorithms: An update. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM). ISBN 0-89871-231-9.

- Dewar, Megan; Stevens, Brett (2012-08-29). Ordering Block Designs - Gray Codes, Universal Cycles and Configuration. CMS Books in Mathematics (1 ed.). New York, USA: Springer Science+Business Media. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4325-4. ISBN 978-1-46144324-7. ISSN 1613-5237. ISBN 1-46144324-5.

- Maxfield, Clive "Max" (2012-10-01) [2011-05-28]. "Gray Code Fundamentals". Design How-To. EETimes. Part 1. Archived from the original on 2017-10-30. Retrieved 2017-10-30. Part 2 Part 3

- Warren Jr., Henry S. (2013). Hacker's Delight (2 ed.). Addison Wesley - Pearson Education, Inc. pp. 311–317. ISBN 978-0-321-84268-8.

External links

- "Gray Code" demonstration by Michael Schreiber, Wolfram Demonstrations Project (with Mathematica implementation). 2007.

- NIST Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures: Gray code

- Hitch Hiker's Guide to Evolutionary Computation, Q21: What are Gray codes, and why are they used?, including C code to convert between binary and BRGC

- Subsets or Combinations Can generate BRGC strings

- Dragos A. Harabor uses Gray codes in a 3D digitizer.

- Single-track gray codes, binary chain codes (Lancaster 1994), and linear feedback shift registers are all useful in finding one's absolute position on a single-track rotary encoder (or other position sensor).

- Computing Binary Combinatorial Gray Codes Via Exhaustive Search With SAT Solvers by Zinovik, I.; Kroening, D.; Chebiryak, Y.

- AMS Column: Gray codes

- Optical Encoder Wheel Generator

- ProtoTalk.net – Understanding Quadrature Encoding – Covers quadrature encoding in more detail with a focus on robotic applications