Prefix sum

In computer science, the prefix sum, cumulative sum, inclusive scan, or simply scan of a sequence of numbers x0, x1, x2, ... is a second sequence of numbers y0, y1, y2, ..., the sums of prefixes (running totals) of the input sequence:

- y0 = x0

- y1 = x0 + x1

- y2 = x0 + x1+ x2

- ...

For instance, the prefix sums of the natural numbers are the triangular numbers:

input numbers 1 2 3 4 5 6 ... prefix sums 1 3 6 10 15 21 ...

Prefix sums are trivial to compute in sequential models of computation, by using the formula yi = yi − 1 + xi to compute each output value in sequence order. However, despite their ease of computation, prefix sums are a useful primitive in certain algorithms such as counting sort,[1] as introduced in Section 2.3 of [2] and they form the basis of the scan higher-order function in functional programming languages. Prefix sums have also been much studied in parallel algorithms, both as a test problem to be solved and as a useful primitive to be used as a subroutine in other parallel algorithms.[3][4][5]

Abstractly, a prefix sum requires only a binary associative operator ⊕, making it useful for many applications from calculating well-separated pair decompositions of points to string processing. [6][7]

Mathematically, the operation of taking prefix sums can be generalized from finite to infinite sequences; in that context, a prefix sum is known as a partial sum of a series. Prefix summation or partial summation form linear operators on the vector spaces of finite or infinite sequences; their inverses are finite difference operators.

Scan higher order function

In functional programming terms, the prefix sum may be generalized to any binary operation (not just the addition operation); the higher order function resulting from this generalization is called a scan, and it is closely related to the fold operation. Both the scan and the fold operations apply the given binary operation to the same sequence of values, but differ in that the scan returns the whole sequence of results from the binary operation, whereas the fold returns only the final result. For instance, the sequence of factorial numbers may be generated by a scan of the natural numbers using multiplication instead of addition:

input numbers 1 2 3 4 5 6 ... prefix products 1 2 6 24 120 720 ...

Inclusive and exclusive scans

Programming language and library implementations of scan may be either inclusive or exclusive. An inclusive scan includes input xi when computing output yi (i.e., ) while an exclusive scan does not (i.e., ). In the latter case, implementations either leave y0 undefined or accept a separate "x−1" value with which to seed the scan. Exclusive scans are more general in the sense that an inclusive scan can always be implemented in terms of an exclusive scan (by subsequently combining xi with yi), but an exclusive scan cannot always be implemented in terms of an inclusive scan, as in the case of ⊕ being max.

The following table lists examples of the inclusive and exclusive scan functions provided by a few programming languages and libraries:

Parallel algorithm

There are two key algorithms for computing a prefix sum in parallel. The first offers a shorter span and more parallelism but is not work-efficient. The second is work-efficient but requires double the span and offers less parallelism. These are presented in turn below.

Algorithm 1: Shorter span, more parallel

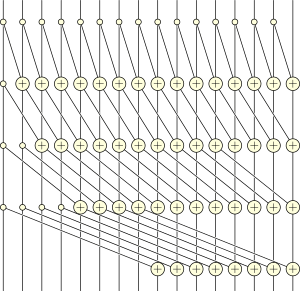

Hillis and Steele present the following parallel prefix sum algorithm:[8]

- for

to

do

- for

to

do in parallel

- if

then

- else

- if

then

- for

to

do in parallel

In the above, the notation means the value of the jth element of array x in timestep i.

Given n processors to perform each iteration of the inner loop in constant time, the algorithm as a whole runs in O(log n) time, the number of iterations of the outer loop.

Algorithm 2: Work-efficient

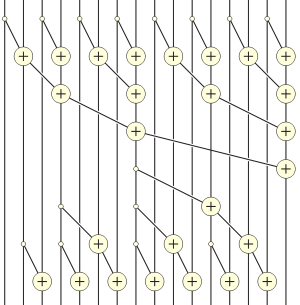

A work-efficient parallel prefix sum can be computed by the following steps.[3][9][10]

- Compute the sums of consecutive pairs of items in which the first item of the pair has an even index: z0 = x0 + x1, z1 = x2 + x3, etc.

- Recursively compute the prefix sum w0, w1, w2, ... of the sequence z0, z1, z2, ...

- Express each term of the final sequence y0, y1, y2, ... as the sum of up to two terms of these intermediate sequences: y0 = x0, y1 = z0, y2 = z0 + x2, y3 = w0, etc. After the first value, each successive number yi is either copied from a position half as far through the w sequence, or is the previous value added to one value in the x sequence.

If the input sequence has n steps, then the recursion continues to a depth of O(log n), which is also the bound on the parallel running time of this algorithm. The number of steps of the algorithm is O(n), and it can be implemented on a parallel random access machine with O(n/log n) processors without any asymptotic slowdown by assigning multiple indices to each processor in rounds of the algorithm for which there are more elements than processors.[3]

Discussion

Each of the preceding algorithms runs in O(log n) time. However, the former takes exactly log2 n steps, while the latter requires 2 log2 n − 2 steps. For the 16-input examples illustrated, Algorithm 1 is 12-way parallel (49 units of work divided by a span of 4) while Algorithm 2 is only 4-way parallel (26 units of work divided by a span of 6). However, Algorithm 2 is work-efficient—it performs only a constant factor (2) of the amount of work required by the sequential algorithm—while Algorithm 1 is work-inefficient—it performs asymptotically more work (a logarithmic factor) than is required sequentially. Consequently, Algorithm 1 is likely to perform better when abundant parallelism is available, but Algorithm 2 is likely to perform better when parallelism is more limited.

Parallel algorithms for prefix sums can often be generalized to other scan operations on associative binary operations,[3][4] and they can also be computed efficiently on modern parallel hardware such as a GPU.[11] The idea of building in hardware a functional unit dedicated to computing multi-parameter prefix-sum was patented by Uzi Vishkin.[12]

Many parallel implementations follow a two pass procedure where partial prefix sums are calculated in the first pass on each processing unit; the prefix sum of these partial sums is then calculated and broadcast back to the processing units for a second pass using the now known prefix as the initial value. Asymptotically this method takes approximately two read operations and one write operation per item.

Data structures

When a data set may be updated dynamically, it may be stored in a Fenwick tree data structure. This structure allows both the lookup of any individual prefix sum value and the modification of any array value in logarithmic time per operation.[13]. However, an earlier 1982 paper [14] presents a data structure called Partial Sums Tree (see Section 5.1) that appears to overlap Fenwick trees; it should be noted that in 1982 the term prefix-sum was not yet as common as it is today.

For higher-dimensional arrays, the summed area table provides a data structure based on prefix sums for computing sums of arbitrary rectangular subarrays. This can be a helpful primitive in image convolution operations.[15]

Applications

Counting sort is an integer sorting algorithm that uses the prefix sum of a histogram of key frequencies to calculate the position of each key in the sorted output array. It runs in linear time for integer keys that are smaller than the number of items, and is frequently used as part of radix sort, a fast algorithm for sorting integers that are less restricted in magnitude.[1]

List ranking, the problem of transforming a linked list into an array that represents the same sequence of items, can be viewed as computing a prefix sum on the sequence 1, 1, 1, ... and then mapping each item to the array position given by its prefix sum value; by combining list ranking, prefix sums, and Euler tours, many important problems on trees may be solved by efficient parallel algorithms.[4]

An early application of parallel prefix sum algorithms was in the design of binary adders, Boolean circuits that can add two n-bit binary numbers. In this application, the sequence of carry bits of the addition can be represented as a scan operation on the sequence of pairs of input bits, using the majority function to combine the previous carry with these two bits. Each bit of the output number can then be found as the exclusive or of two input bits with the corresponding carry bit. By using a circuit that performs the operations of the parallel prefix sum algorithm, it is possible to design an adder that uses O(n) logic gates and O(log n) time steps.[3][9][10]

In the parallel random access machine model of computing, prefix sums can be used to simulate parallel algorithms that assume the ability for multiple processors to access the same memory cell at the same time, on parallel machines that forbid simultaneous access. By means of a sorting network, a set of parallel memory access requests can be ordered into a sequence such that accesses to the same cell are contiguous within the sequence; scan operations can then be used to determine which of the accesses succeed in writing to their requested cells, and to distribute the results of memory read operations to multiple processors that request the same result.[16]

In Guy Blelloch's Ph.D. thesis[17], parallel prefix operations form part of the formalization of the Data parallelism model provided by machines such as the Connection Machine. The Connection Machine CM-1 and CM-2 provided a hypercubic network on which the Algorithm 1 above could be implemented, whereas the CM-5 provided a dedicated network to implement Algorithm 2.[18]

In the construction of Gray codes, sequences of binary values with the property that consecutive sequence values differ from each other in a single bit position, a number n can be converted into the Gray code value at position n of the sequence simply by taking the exclusive or of n and n/2 (the number formed by shifting n right by a single bit position). The reverse operation, decoding a Gray-coded value x into a binary number, is more complicated, but can be expressed as the prefix sum of the bits of x, where each summation operation within the prefix sum is performed modulo two. A prefix sum of this type may be performed efficiently using the bitwise Boolean operations available on modern computers, by computing the exclusive or of x with each of the numbers formed by shifting x to the left by a number of bits that is a power of two.[19]

Parallel prefix (using multiplication as the underlying associative operation) can also be used to build fast algorithms for parallel polynomial interpolation. In particular, it can be used to compute the divided difference coefficients of the Newton form of the interpolation polynomial.[20] This prefix based approach can also be used to obtain the generalized divided differences for (confluent) Hermite interpolation as well as for parallel algorithms for Vandermonde systems.[21]

See also

References

- 1 2 Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001), "8.2 Counting Sort", Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.), MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, pp. 168–170, ISBN 0-262-03293-7 .

- ↑ Cole, Richard; Vishkin, Uzi (1986), "Deterministic coin tossing with applications to optimal parallel list ranking", Information and Control, 70 (1): 32–53, doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(86)80023-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ladner, R. E.; Fischer, M. J. (1980), "Parallel Prefix Computation", Journal of the ACM, 27 (4): 831–838, doi:10.1145/322217.322232, MR 0594702 .

- 1 2 3 Tarjan, Robert E.; Vishkin, Uzi (1985), "An efficient parallel biconnectivity algorithm", SIAM Journal on Computing, 14 (4): 862–874, doi:10.1137/0214061 .

- ↑ Lakshmivarahan, S.; Dhall, S.K. (1994), Parallelism in the Prefix Problem, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19508849-2 .

- ↑ Blelloch, Guy (2011), Prefix Sums and Their Applications (Lecture Notes) (PDF), Carnegie Mellon University .

- ↑ Callahan, Paul; Kosaraju, S. Rao (1995), "A Decomposition of Multi-Dimensional Point Sets with Applications to k-Nearest-Neighbors and n-Body Potential Fields", Journal of the ACM, 42 (1), doi:10.1145/200836.200853 .

- ↑ Hillis, W. Daniel; Steele, Jr., Guy L. (December 1986). "Data parallel algorithms". Communications of the ACM. 29 (12): 1170–1183. doi:10.1145/7902.7903.

- 1 2 Ofman, Yu. (1962), Об алгоритмической сложности дискретных функций, Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian), 145 (1): 48–51, MR 0168423 . English translation, "On the algorithmic complexity of discrete functions", Soviet Physics Doklady 7: 589–591 1963.

- 1 2 Khrapchenko, V. M. (1967), "Asymptotic Estimation of Addition Time of a Parallel Adder", Problemy Kibernet. (in Russian), 19: 107–122 . English translation in Syst. Theory Res. 19; 105–122, 1970.

- ↑ Sengupta, Shubhabrata; Harris, Mark; Zhang, Yao; Owens, John D. (2007). Scan primitives for GPU computing. Proc. 22nd ACM SIGGRAPH/EUROGRAPHICS Symposium on Graphics Hardware. pp. 97–106.

- ↑ Vishkin, Uzi (2003). Prefix sums and an application thereof. U.S. Patent 6,542,918.

- ↑ Fenwick, Peter M. (1994), "A new data structure for cumulative frequency tables", Software: Practice and Experience, 24 (3): 327–336, doi:10.1002/spe.4380240306

- ↑ Shiloach, Yossi; Vishkin, Uzi (1982b), "An O(n2 log n) parallel max-flow algorithm", Journal of Algorithms, 3 (2): 128–146, doi:10.1016/0196-6774(82)90013-X

- ↑ Szeliski, Richard (2010), "Summed area table (integral image)", Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications, Texts in Computer Science, Springer, pp. 106–107, ISBN 9781848829350 .

- ↑ Vishkin, Uzi (1983), "Implementation of simultaneous memory address access in models that forbid it", Journal of Algorithms, 4 (1): 45–50, doi:10.1016/0196-6774(83)90033-0, MR 0689265 .

- ↑ Blelloch, Guy E. (1990). Vector models for data-parallel computing. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 026202313X. OCLC 21761743.

- ↑ Leiserson, Charles E.; Abuhamdeh, Zahi S.; Douglas, David C.; Feynman, Carl R.; Ganmukhi, Mahesh N.; Hill, Jeffrey V.; Hillis, W. Daniel; Kuszmaul, Bradley C.; St. Pierre, Margaret A. (March 15, 1996). "The Network Architecture of the Connection Machine CM-5". Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing. 33 (2): 145–158. doi:10.1006/jpdc.1996.0033. ISSN 0743-7315.

- ↑ Warren, Henry S. (2003), Hacker's Delight, Addison-Wesley, p. 236, ISBN 978-0-201-91465-8 .

- ↑ Eğecioğlu, O.; Gallopoulos, E.; Koç, C. (1990), "A parallel method for fast and practical high-order Newton interpolation", BIT Computer Science and Numerical Mathematics, 30 (2): 268–288, doi:10.1007/BF02017348 External link in

|journal=(help) . - ↑ Eğecioğlu, O.; Gallopoulos, E.; Koç, C. (1989), "Fast computation of divided differences and parallel Hermite interpolation", Journal of Complexity, 5: 417–437, doi:10.1016/0885-064X(89)90018-6 External link in

|journal=(help)