Battle of Capo d'Orso

Coordinates: 40°36′N 14°36′E / 40.600°N 14.600°E

| Battle of Capo d’Orso | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the League of Cognac | |||||||

View at Amalfi, Bay of Salerno, George Loring Brown, 1857. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10 ships

300 soldiers |

12 main ships

Many lesser vessels | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

500 dead |

700 dead | ||||||

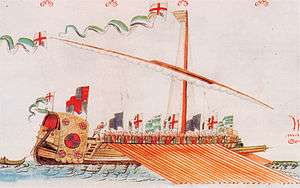

The Battle of Capo d'Orso, sometimes known as the Battle of Cava and the Battle of Amalfi was a naval engagement taking place over two days, on April 28 and April 29, 1528 when a French fleet inflicted a crushing defeat on the fleet of the Kingdom of Naples under Spanish control in the Gulf of Salerno, where the Spanish forces sailing southwards from their naval station in Naples trying to break the French blockade of the city meet the French fleet.

The battle gives the French a complete command of the sea. Tactically, it shows the superiority of the chosen Genoese galleys over the slower and less agile Spanish ones, despite the presence aboard of a large party of veteran Spanish soldiers. As noted by a witness, Paolo Giovio, "the victory came from crafty seamanship rather than brute force".[1]

Background

Francis I of France, after his humiliating defeat at Pavia in 1525 rekindled the war in Italy, this time with the support of Pope Clement VII, the Republic of Venice, the Kingdom of England, the Duchy of Milan and Republic of Florence, all parts to the League of Cognac and worried of the ascendency of Charles V in Italy and in Europe. The conflict begins in 1526.

Despite some important initial successes such as the sack of Rome in 1527, the Spanish army is quickly disintegrating due to a dramatic lack of funding. By the end of 1527, a French army under the viscount of Lautrec is moving southwards from Central Italy, capturing cities one by one and rapidly pushing the Spaniards out of their prized possession in the region, the Kingdom of Naples. If the city of Naples was to fall into French hands, Charles V would lose his last foothold in the peninsula and France would become the dominating power in the central Mediterranean.

The blockade of Naples

Mid-April, the French forces under the viscount of Lautrec reach the walls of Naples. The city is well defended and attempts to seize it by force by land and sea are pushed back. A real siege begins. The French cut the aqueducts bringing fresh water to Naples and, as the city has but a few wells thirst quickly becomes a problem for the besieged.[2] Food supply are also fairly low. The Spaniards have but twenty days worth of wine and meat a between three and five months of grain. The French have also captured the main mills of the region and there are none in the city, forcing the Spaniards to use the extremely labour-intensive hand-mills. Spies notify the Venetians of several mutinies among in the army among German, Italian as well as Spanish regiments.[3]

Naples can also be supplied from the sea as Sicily is rich in grains and still in Spanish hands. The French dispatch to Naples part of their fleet, namely a squadron of galleys belonging to the mercenaries shipowners Andrea Doria and Antonio Doria hired by the French since 1522. This squadron is under the command of the nephew of Andrea Doria, Filippino and with the Genoese nobleman Nicolò Lomellino as second in command. The patrols of the French navy prevents the arrival of supplies from Sicily – two ships carrying wheat for the besieged Neapolitans are intercepted by Filippino Doria mid-April. The fleet also captures several points along the coastline (Capri, Pozzuoli, Castelammare and Procida).[4] The number of vessels in the French fleet is however insufficient to keep the blockade completely tight as the galleys cannot spend more than a few hours at sea at the time and the French galleys need to return to their base near Salerno every night. The French refuse to allow Andrea Doria to send more galleys in reinforcement to Southern Italy as they are expecting the prompt reinforcement of the Venetian fleet, then sailing around Apulia, to seal off the city completely.[5] But the Venetians are delayed by the sore state of their galleys and several operations against Spanish stronghold in Apulia such as Monopoli, Otranto and Lecce.[6]

In the city, the Spaniards await naval reinforcement from Sicily,[7] but it fails to materialise. The Naples squadron will have to face the French on its own. It is made out of galleys rented from Castilian, Catalan and Italian shipowner serving at will for the Spanish Crown.[8] With only six large galleys, it is outnumbered and outgunned by the French eight vessels. Typically, the Spanish captains avoid contact with the enemy and rests on stealth for their operations outside the harbour. For instance, hoping to go unnoticed and to be able to land in Gaeta or Castelammare where they could use the windmills to grind their grain into flour, the Spanisn fleet takes to the sea in the morning of April 27. But the Neapolitan squadron is rapidly spotted by the French who manoeuvre to intercept the Neapolitan galleys. Unprepared for battle, the Spanish fleet opts for a hasty retreat back to the safety of the harbour.[9]

The Spanish plan of action

Despite their inferiority, the Spanish command decides to attack the French fleet. Historian Maurizio Arfaioli hypotheses that the choice may have been the result of a power play within the Spanish high-command as Hugo de Moncada, veteran of many campaigns in the Mediterranean, saw a naval operation as the best chance to counter the prominence of the young Philibert of Chalon, prince of Orange, a brilliant general but who had never fought on the sea.[10] The squabble of the Spanish generals leads to the designation of a third man as the chief of the flotilla: Alfonso d'Avalos, marchese del Vasto[11] but don Hugo joins nonetheless the fleet, albeit not as its main commander, while Philipert de Chalon remains in Naples.

Aware of the greater seamanship of the Genoese, the Spaniards decide to fill their galleys with "chosen troops" to guaranty their superiority during the hand-to-hand phase of the combat, once ships are locked one with the other and boarding parties sent onto the enemy's vessels. Some 700 veteran Spanish soldiers and 200 German Landsknechts under the command of Konrad Glorn are embarked on the galleys to complement the Spanish marines.[12][13] To make the Spanish fleet appear larger than it really is, it is decided that dozens of lesser vessels will join the galleys.

Steps are also taken to ensure the loyalty of the Genoese navy officers and sailors serving on the Neapolitan squadron as the Spaniards are to be confronted to a French fleet heavily manned by their fellowcountrymen. The commander of the Neapolitan squadron, Fabrizio Giustiniani, in particular, is suspected as he happens to he the father-in-law of Antonio Doria, one of the main mercenaries serving on the French side.[14]

Order of battle

| The Spanish fleet |

|

| The French fleet |

The battle

The approach

.jpg)

In the evening of April 27, the Spanish fleet exits anew the port of Naples and sails westwards one and half nautical mile to Posillipo just outside the city walls and spends the night there. In the early hours of the morning of April 28, the Spanish fleets sails south to Capri, 17 nautical miles away from Naples. This time, the Spanish fleet has been spotted late by the French lookouts and the fleet of Filippino Doria is still grounded in Salerno. The Spaniards can sail unopposed in the Bay of Naples and potentially catch the French fleet still anchored and unable to fight them.[43]

Filippino Doria dispatches a pressing demand for reinforcement to the French commander, the viscount of Lautrec. But the French camp is far away and no support will reach the fleet before the mid-afternoon. Several authors of the time mention that once in Capri, the Spanish officers of the Spanish fleet lunch leisurely (Hugo de Moncada has apparently brought musicians with him) and the men listen to a protracted sermon by Portuguese hermit Gonsalvo Baretta (who entices them to fight the Genoese, qualified of "white Moors").[44][45] The Spanish fleet leaves Capri in the afternoon, overtakes the Punta della Campanella and proceeds due East towards Amalfi. The delays caused by the lunch and the hermit's sermon are long enough for the French reinforcements to reach the fleet. At 4:00PM, some 300 Gascon musketeers under the command of Gilbert du Croq[46] arrive at Vietri and are hastily embarked on the galleys to complement the Genoese marines. The French fleet then sails due East towards the Spanish squadron.[47][48]

Early Spanish success

With dozens of vessels, the Spanish fleets looks very impressive and three French ships – the Nettuna, the Segnora and the Mora – break formation and escape southward. With his remaining vessels Filippino Doria is largely outnumbered. The Genoese sailors, aware of the disadvantage, consider themselves as good as dead.[49] The Genoese captain engages the enemy nonetheless around 5:00PM.[50] The French fleet opens fire first with the large guns of the bow. One of the shots from Filippino Doria's Capitana main basilisco kills 32 Spanish soldiers and officers aboard the Capitana of d'Avalos.[51][52] The Spanish artillery, on the other hand, is largely ineffective. The Spanish infantry, exposed on the galleys, is also submitted to heavy fire from the Gascons musketeers protected by a palisade aboard the French ships.[53] But the crew of the Spanish manages to grapple the French flagship and the Spanish soldiers board the adversary.

Despite the losses, the rest Spanish fleet manages nonetheless to manoeuvre and to begin to board three of the four other remaining French galleys.[54] On the northern flank, the Neapoletan Gobba, the Secana and the Santa Croce surround the French Pellegrina and the Donzella. The boarding parties are led by captains Cesare Fieramosca and Garcia Manrique de Lara.[55][56] Both French vessels are in great difficulty and about to be captured.[57] Meanwhile, on the southern flank, the German landsknechts aboard the Spanish galleys Perpignana and Calabresa also reach close-quarter combat with the French vessels Fortuna and Sirena.[58] The Sirena is isolated and captured.[59]

French counter-attack

Severely out-numbered, the French are unlikely to hold long. But, while the battle is raging, the three French ships which had broken formation earlier change path and return to the fight. It was a ruse of Filippino Doria performed by his second-in-command, the mercenary and Genoese nobleman, Nicolò Lomelino. Travelling North-East in the late afternoon, the three galleys may have been hidden from view by the sunset and to have gone undetected by the Spanish fleet.

The three ships of Nicolò Lomelino attack the Spanish Capitana from the rear. After being hit by artillery, the Spanish flagship and is rammed by Lomellino's Nettuna.[60] The hand-to-hand battle that ensues is particularly bloody. Several Spanish officers are killed, including don Hugo de Moncada, hit by two arquebuse balls. He dies shouting “Fight brothers, victory is ours”.[61] The Genoese soldiers show great skill in the combat by, as a witness remarked later, "like leopards leaping from one galley to the next".[62] Casualties are mounting on both sides, the Gascons have lost over half their men and the French are still significantly outnumbered and find themselves in difficulty. To tip the scales in his favour, Filippino Doria frees the rowers, the ciurma, made of delinquants, criminals and Muslim captives from their chains and promises their freedom if they fight for him.[63] They accept and board the Spanish vessels. Defeated, the few surviving Spaniards must surrender.

The three galleys of Lomellini then turn to three other Spanish galleys, the Pellegrina, the Donzella and the Gobba.[64] As they approach, the French ships unleash “a storm of cannonballs thick as a hail”. Fabrizio Giustiniani, "il Gobbo" is wounded and out-of-combat and the Neapolitan captain Cesare Fieramosca, in charge of the infantry, is thrown into the sea by a direct hit. The Spanish galleys Gobba is boarded and must surrender. The Spanish troops on the other two galleys, despite support from two brigantines and two basque sailboats are now in clearly outnumbered. Their oars are broken and they are beginning to sink so they cannot disengage and escape. The Spanish troops must give up the fight and surrender as the two galleys sink. The Spanish captain and sailor Bernardo Villamarino, the constable Ascanio Colonna and Camillio Colonna, his brother, are made prisoners. The two fustes supporting them are also captured.[65]

The last two Spanish galleys, the Calabresa and the Perpignana are still engaged with the rest of the French fleet. A French boarding party, led by François de Scépeaux de Vieilleville, has even managed to take hold of part of the Perpignana. Seeing the day is lost, the crews of the Spanish vessels are nonetheless able to cut off the grapnels that tie them to the French galleys and to sail away – with the French party on board, now taken prisoners.[66] It is about 9:00PM ("ad una hora di notte"), the battle has lasted four hours.[67]

Later developments

The Calabresa is the first to return to Naples. Angered by what he considers as cowardice, the Prince of Orange has all the officers of the ship, including its captain, the Catalan Francès de Loria, immediately hanged in full view of the harbour.[68][lower-alpha 1] Understanding what awaits him, Orazio, the captain of the second galley decides not to return to Naples and heads Westwards with its French prisoners aboard and disappears in the dark.[69]

The following day, the Prince of Orange launches the Calabresa refitted and under a new captain in pursuit of Orazio.[70] He encounters him near Capri towing a French galley apparently captured during the night. But as the Calabresa approaches, Orazio opens fire on the Spanish vessel. He has changed side during the night and boards the Spanish vessel along with the French troops of the galley he was towing. The new captain of the Calabresa, Alfonso Caraccioli has to surrender.[71]

Aftermath

The Neapolitan squadron has been entirely wiped out during the battle and its aftermath. The Spaniards cannot hope to break through the French blockade anymore. Worried about the fate of their husbands, the women of Naples deputise Paolo Giovio to enquire about the losses.[72] He reports that 700 to 800 men have been killed on the Spanish side ("the flower of the Spanish army")[73] and that about as many have been taken prisoners by the French.[74][75] Numerous nobles and high-ranking militaries and administrators are either dead or captives, including the commander of the fleet Alfonso d'Avalos.[76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84] Among the soldiers, the losses are staggering. On the Spanish Capitana, every single one of the 150 soldiers has been killed, on the Gobba 103 out of 108 soldiers have fallen.[85] Paolo Giovio's description of the galleys after the battle is most gruesome.[86]

On the French side, the losses are also very heavy as the majority of the Gascon musketeers and a good many of the Genoese marines have perished. About 500 of the men of Filippino Doria are dead.[87] On some galleys, the French have lost 75% of their soldiers.[88] The cardinal Pompeo Colonna notes soon after that "it was the cruelest and bloodiest (sanguinolenta) battle fought on the sea in our times".[89] Pope Clement saw the Spanish defeat as a just punishment for those who had sacked the Holy City a year prior, declaring: "the immortal God has not been a hesitant and tardy avenger of this infamous crime"[90]

The siege of Naples continues on land as well as on sea. On May 1, the French captain in charge of the Gascon musketeers at the battle of Capo d'Orso is killed under the walls of the city.[91] But the long-awaited Venetian fleet arrives on June 11, thus tightening a bit more the blockade of the city.[92] On May 13, the news of the battle reach the French king in Paris and a te deum mass is immediately held in Notre Dame de Paris.[93] In Naples, food supplies are being quickly exhausted, on June 14, the Prince of Orange already writes about scarcities. At best the city can hold for a few more weeks before famine forces the Spanish troops to surrender.

The victors, however, have started to squabble about the prisoners. The Genoese mercenaries, in particular, refuse to hand the main Spanish prisoners to the viscount of Lautrec as the French have before kept the ransoms for themselves. Instead, Filippino Doria dispateches the most important captives to his uncle in Genoa.There the Marchese d'Avalos opens negotiations with the Genoese admiral for him to change side with his private fleet. During the month of June, letters are exchanged with Charles, emperor and king of Spain. Finally, on June 30, Andrea Doria declares himself in favour of the Habsburgs and withdraws his support to France. By July 4, the news reaches Naples and Filipino Doria abandons the siege of Naples with his galleys.[94]

The sea blockade of Naples is lifted while an epidemics breaks out in the French camps and thins out the ranks of the besiegers. On August 15, the viscount of Lautrec himself succumbs to the disease and the French troops must withdraw from Southern Italy.

In popular culture

Unlike many famous battles of the century such as Marignano, Pavia or Lepanto, the battle of Capo d'Orso has generated little attention. There seems however to exist a long poem compose by a participant to the Ludovico di Lorenzo Martèlli describing the engagement, written during the poet's three-month captivity in Genoa.[95]

Notes

- ↑ While probably unfair, the punishment imposed on Francès de Loria is not extraordinary. In 1556, the Spanish officer Alonso Peralta was beheaded for abandoning Bejaia to the Algerians and Gaspard de Vallier was stripped of his cloak as a knight of Saint-John in 1551 for having abandoned Tripoli to the Ottomans.

References

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 296

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 295

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 221

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 221

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 292

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 295

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 220

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 295

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 341

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 221

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 296

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Graziani 2013

- ↑ Almagià 1935

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Almagià 1935

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Almagià 1935

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Almagià 1935

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Almagià 1935

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Almagià 1935

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 340

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 222

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 341

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 222

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 296

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 340

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 342

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 296

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ Guilmartin 2013, p. 99

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 223

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 224

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 224

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 342

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 342

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 224

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 224

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 224

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 346

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 225

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 225

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 343

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 224

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 296

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 224

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 224

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 227

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 227

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 226

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 296

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 225

- ↑ Almagià 1935

- ↑ Cosentino 2008

- ↑ Robert 1902, pp. 190–191

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 296

- ↑ Cavanna Ciappina 2001

- ↑ De Negri 1997

- ↑ Farinella 2001

- ↑ Petrucci 1982

- ↑ Petrucci 1982

- ↑ Robert 1902, p. 189 et seg.

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 339

- ↑ Arfaioli 2001, p. 344

- ↑ Almagià 1935

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 226

- ↑ Setton 1984, p. 297

- ↑ Musiol 2013, p. 116

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 227

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 228

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 228

- ↑ De La Roncière 1906, p. 228

- ↑ Cosentino 2008

Bibliography

- Almagià, Guido (1935). "Capo d'Orso". Enciclopedia Italiana.

- Arfaioli, Maurizio (2001). The road to Naples: Florence, the Black Bands and the army of the League of Cognac (1526-1528) (PDF). Warwick: University of Warwick.

- Calabria, Antonio (2002). The Cost of Empire: The Finances of the Kingdom of Naples in the Time of Spanish Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cavanna Ciappina, Maristella (1982). "Doria, Filippo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 41.

- Campodonico, Pierangelo (1997). Andrea Doria. Genoa: Tormena Editore.

- Capelloni, Lorenzo (1863). Vita del principe Andrea Doria. Genoa: V. Canepa.

- Cavanna Ciappina, Maristella (2001). "Giustiniani, Galeazzo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 57.

- Cavanna Ciappina, Maristella (1992). "Doria, Filippo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 41.

- Cosentino, Paola (2008). "Martelli, Lodovico". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 71.

- De Caro, Gaspare (1962). "Avalos, Alfonso d', marchese del Vasto". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 4.

- De La Roncière, Charles (1906). Histoire de la marine française. Vol. III. Les Guerres d'Italie. Paris: Librairie Plon.

- De Negri, Felicita (1997). "Fieramosca, Cesare". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 47.

- Farinella, Calogero (2001). "Giustiniani, Bricio". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 57.

- Fernández Duro, C. (1972). Armada Española, tomo I. Madrid: Museo Naval.

- Giovio, Paolo (1564). Delle istorie di mons. Giouio. Venice: Giorgio de Cavalli.

- Guicciardini, F. (1971). Storia d’Italia. Turin: Einaudi.

- Guilmartin, John Francis (2003). Gunpowder & Galleys: Changing Technology & Mediterranean Warfare at Sea in the 16th Century. Washington: Naval Institute Press.

- Graziani, Antoine-Marie (2013). Andrea Doria. Paris: Tallandier.

- Lo Basso, Luca (2007). "Gli asentisti del re. L'esercizio privato della guerra nelle strategie economiche dei Genovesi (1528-1716)" (PDF). R. Cancila. Mediterraneo in armi. Mediterranea. Palermo: 2712–81.

- Manfroni, C. (1901). Storia della Marina italiana. Vol. III. Livorno: Regia Accademia Navale.

- Musiol, Maria (2013). Vittoria Colonna: A Female Genius of Italian Renaissance. Berlin: epubli GmbH.

- Pedìo, Tommaso (1971). Napoli e Spagna nella prima metà del Cinquecento. Bari: F. Cacucci.

- Pedìo, Tommaso (1974). Gli spagnoli alla conquista dell'Italia. Reggio Calabria: Editori riuniti meridionali.

- Pelaez, Mario (1934). "Martelli, Ludovico". Enciclopedia Italiana.

- Petrucci, Franca (1982). "Colonna, Camillo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 27.

- Petrucci, Franca (1982). "Colonna, Ascanio". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 27.

- Price Zimmermann, T. C. (2001). "Giovio, Paolo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 56.

- Robert, Ulysse (1902). Philibert de Châlon. Prince d'Orange, Vice-Roi de Naples (18 mars 1502-3 août 1530). Paris: Plon, Nurrit et Cie.

- Saletta, Vincenzo (1975). La spedizione di Lautrec contro il Regno di Napoli: contributo alla storia del Mezzogiorno d'Italia. Roma: C. E. S. M.

- Santoro, Leonardo (1858). Dei successi del sacco di Roma e guerra del regno di Napoli sotto Lotrech. Naples: Androsio.

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, (1204-1571). Vol. III. The Sixteenth Century. New York: American Philosophical Society.

- Troso, Mario (2001). Italia! Italia! 1526-1530: la prima guerra d'indipendenza italiana : con gli assedi di Milano, Napoli, Firenze, il sacco di Roma e le battaglie di Capo d'Orso e Gavinana. Parma: E. Albertelli.

- Vitale, Vito Antonio (1934). "Lomellini". Enciclopedia Italiana.

- Völkel, Markus (1999). Die Wahrheit zeigt viele Gesichter: der Historiker, Sammler und Satiriker Paolo Giovio (1486-1552) und sein Porträt Roms in der Hochrenaissance. Basel: Schwabe.

- Williams, Philip (2014). Empire and Holy War in the Mediterranean: The Galley and Maritime Conflict between the Habsburgs and Ottomans. New York: I.B.Tauris.