Battle of Auberoche

| Battle of Auberoche | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Gascon campaign of the Hundred Years War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,200 | 7,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | Heavy | ||||||

The Battle of Auberoche was fought on 21 October 1345 during the Gascon campaign of 1345 between an Anglo-Gascon force of 1,200 men under Henry, Earl of Derby and a French army of 7,000 commanded by Louis of Poitiers. It was fought at the village of Auberoche near Périgueux in northern Aquitaine. At the time, Gascony was a territory of the English crown and the Anglo-Gascon army included a large proportion of native Gascons. The battle resulted in a decisive English victory, with heavy French casualties.

The battle took place during the early stages of the Hundred Years War. Along with the Battle of Bergerac earlier in the year, it marked a change in the military balance of power in the region as the French position subsequently collapsed. It was the first of a series of victories which would lead to Henry of Derby being called "one of the best warriors in the world" by a contemporary chronicler in Chroniques de quatres premier Valois.[1]

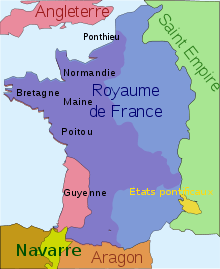

Background

Since the Norman Conquest of 1066, English monarchs had held titles and lands within France, the possession of which made them vassals of the kings of France. The status of the English king's French fiefs was a major source of conflict between the monarchies throughout the Middle Ages. French monarchs systematically sought to check the growth of English power, stripping away lands as the opportunity arose.[2] Over the centuries, English holdings in France had varied in size, but by 1337 only Gascony (and Ponthieu) were left.[3] The Gascons had their own language and customs. A large proportion of the red wine that they produced was shipped to England in a profitable trade. The trade provided the English king with much of his revenue. The Gascons preferred their relationship with a distant English king who left them alone, to one with a French king who would interfere in their affairs.[4][5]

Following a series of disagreements between Philip VI of France and Edward III of England, on 24 May 1337, Philip's Great Council in Paris agreed that the Duchy of Aquitaine, effectively Gascony, should be taken back into Philip's hands on the grounds that Edward was in breach of his obligations as a vassal. This marked the start of the Hundred Years' War, which was to last one hundred and sixteen years.[6] Although Gascony was the cause of the war, Edward was able to spare few resources for it and whenever an English army campaigned on the continent it operated in northern France. In most campaigning seasons the Gascons had had to rely on their own resources and had been hard pressed by the French.[7][8] In 1339 the French besieged Bordeaux, the capital of Gascony, even breaking into the city with a large force before they were repulsed.[9]

Edward determined early in 1345 to attack France on three fronts. The Earl of Northampton would lead a small force to Brittany, a slightly larger force would proceed to Gascony under the command of the Earl of Derby and the main force would accompany Edward to France or Flanders.[10][11] The previous Seneschal of Gascony, Nicholas de la Beche, was replaced by the more senior Ralph, Earl of Stafford, who sailed for Gascony in February with an advance force. Derby was appointed the King's Lieutenant in Gascony on 13 March 1345[12] and received a contract to raise a force of 2,000 men in England, and further troops in Gascony itself.[13]

In early 1345 the French decided to stand on the defensive in the south west. Their intelligence correctly predicted English offensives in the three theatres, but they did not have the money to raise a significant army in each. They anticipated, correctly, that the English planned to make their main effort in northern France. Thus they directed what resources they had to there, planning to assemble their main army at Arras on 22 July. South western France was encouraged to rely on its own resources, but as the Truce of Malestroit, signed in early 1343, was still in effect, the local lords were reluctant to spend money, and little was done.[14]

Prelude

Derby's force embarked at Southampton at the end of May. Due to bad weather, his fleet was forced to shelter in Falmouth for several weeks en route, finally departing on 23 July.[15] The Gascons, primed by Stafford to expect Derby's arrival in late May and sensing the French weakness, took the field without him, breaking the tenuous Truce of Malestroit. Stafford made a short advance to besiege the French strongholds of Blaye and Langdon with his advance party and perhaps 1,000 men-at-arms and 3,000 infantry of the Gascon lords.[16] Meanwhile, small independent parties of Gascons raided across the region. They had a number of significant successes, but their main effect was to tie down most of the weak French garrisons in the region and to cause them to call for reinforcements. The few mobile French troops in the region immobilised themselves by laying siege to Montcuq, an insignificant castle south of Bergerac, under the command of Henri de Montigny, Seneschal of Périgord.[17]

Edward III's main army sailed on 29 June. They anchored off Sluys in Flanders until 22 July while Edward attended to diplomatic affairs.[18] When they sailed, probably intending to land in Normandy, they were scattered by a storm and found their way to various English ports over the following week. After more than five weeks on board ship the men and horses had to be disembarked. There was a further week's delay while the King and his council debated what to do, by which time it proved impossible to take any action with the main English army before winter.[19] Aware of this, Philip VI of France despatched reinforcements to Brittany and Gascony. Peter, Duke of Bourbon was appointed commander-in-chief of the south west front on 8 August.[20]

On 9 August 1345 Derby arrived in Bordeaux with 500 men-at-arms, 500 mounted archers and 1,000 English and Welsh foot archers.[8] After two weeks recruiting and organising Derby marched his force to Langdon, rendezvoused with Stafford and took command of the combined force.[21] Stafford had to this point pursued a cautious strategy of small-scale sieges. Derby's intention was quite different.[22] The French, hearing of Derby's arrival, concentrated their forces at the strategically important town of Bergerac, where there was an important bridge over the Dordogne River.[21][23] After a council of war Derby decided to strike at the French here. The capture of the town, which had good river supply links to Bordeaux, would provide the Anglo-Gascon army with a base from which to carry the war to the French.[24] It would also force the lifting of the siege of the nearby allied castle of Montcuq and sever communications between French forces north and south of the Dordogne. The English believed that if the French field army could be beaten or distracted the town could be easily taken.[25]

Derby moved rapidly and took the French army by surprise. In a running battle they were decisively beaten. French casualties were heavy, with many killed and a large number captured, including their commander. The surviving French from their field army rallied around John, Count of Aramagnac, and retreated north to Périgueux.[26] Within days of the battle, Bergerac fell to an Anglo-Gascon assault and was subsequently sacked.[27] After consolidating and reorganising for two weeks Derby left a large garrison in the town and moved north to the Anglo-Gascon stronghold of Mussidan in the Isle valley with 6,000–8,000 men.[28] He then pushed west to Périgueux, the provincial capital,[10] taking several strongpoints on the way.{sfn|Fowler|1961|p=196}}

The city's defences were antiquated and derelict, but the size of the French force defending it prohibited an assault. Derby blockaded Périgueux and captured a number of strongholds blocking the main routes into the city. John, Duke of Normandy, the son and heir of Philip VI, gathered a reportedly vast army and manoeuvred in the area. In early October a very large detachment relieved the city and drove off Derby's force, which withdrew towards Bordeaux. Further reinforced the French started besieging the English held strongpoints.[29]

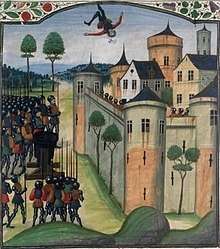

Siege

The main French force of 7,000, commanded by Louis of Poitiers, besieged the castle of Auberoche, 9 miles (14 km) east of Périgueux. Auberoche perches on a rocky promontory completely commanding the River Auvézère and the valley road at a point where the valley narrows almost to a gorge. The small Anglo-Gascon garrison was commanded by Sir Frank Halle.[30] The chronicler Froissart tells a tale, most likely apocryphal, that a soldier attempting to reach English lines with a letter requesting help was captured and returned to the castle via a trebuchet which caused him grievous injuries.[31] A messenger did get through French lines and reached Derby, who was already returning to the area with a scratch force of 1,200 English and Gascon soldiers: 400 men-at-arms and 800 mounted archers.[32]. The French encampment was divided in two, with the majority of the soldiers camped close to the river between the castle and village while a smaller force was situated to prevent any relief attempts from the north.[32]

Battle

%2C_f.8_-_BL_Stowe_MS_594_(cropped).jpg)

Knowing he was outnumbered, Derby waited near Périgueux for several days for the arrival of a force under the Earl of Pembroke. Unknown to Derby, another French army of some 9,000–10,000 men under the Duke of Normandy was only 25 miles (40 km) away.[33] On the evening of 20 October Derby decided that waiting any longer would invite an attack from the larger French army and made a night march, crossing the shallow river twice, so that by morning he was situated on a low wooded hill about a mile from the main French camp in the valley by the river. Derby personally reconnoitred the French position. Still hoping for the last-minute arrival of Pembroke, Derby called a council of his officers. It was decided that rather than wait and possibly lose the advantage of surprise, the army would attack immediately and attempt to overrun the French camp before an effective defence could be devised.[10][30]

Derby planned a three-pronged assault. The attack was launched as the French were having their evening meal, and complete surprise was achieved. His longbowmen fired from the treeline to the west into the French position. The French, packed tightly into the narrow meadow, not expecting an attack and unarmoured, are reported to have taken heavy casualties from this. Adam Murimuth, a contemporary chronicler, estimates French casualties at this stage at around 1,000.[34] While the French were confused, and distracted by this attack from the west, Derby made a cavalry charge with his 400 men-at-arms from the south. They had some 200–300 yards (200–300 m) across flat ground to cover to reach the French. French soldiers struggled into their armour and their commanders rallied their still superior forces. A small Anglo-Gascon infantry had followed a path in the woods to emerge in the French rear and now attacked from the north west. The fighting continued in the area of the camp for some time. Halle, realising that the French troops guarding his exit from the castle were either distracted or had been drawn off to join the fighting, sallied with all the mounted men he could muster. Taken in the rear, the French defence collapsed and they routed, pursued by the English cavalry.[10][30]

French casualties are uncertain, but were heavy. They are variously described by modern historians as "appalling",[35] "extremely high",[10] "staggering",[36] and "heavy".[30] Many French nobles were taken prisoner; lesser men were, as was customary, put to the sword. The French commander, Louis of Poitiers, died of his wounds. Surviving prisoners included the second in command, Bertrand de l'Isle-Jourdain, two counts, seven viscounts, three barons, the seneschals of Clermont and Toulouse, a nephew of the Pope and so many knights that they were not counted.[35]

Aftermath

The French left behind them a large quantity of loot and supplies. This was in addition to the ransoms extracted from the French captives for their release, which was due to the individuals who had captured them, shared with their liege lords. The ransoms alone made a fortune for many of the soldiers in Derby's army, as well as Derby himself, who was said to have made at least £50,000 (£45,000,000 as of 2018[note 1] ) from that day's captives.[33]

The Duke of Normandy lost heart on hearing of the defeat. Despite outnumbering the Anglo-Gascon force eight to one he retreated to Angoulême and disbanded his army. The French also abandoned all of their ongoing sieges of other Anglo-Gascon garrisons.[30] Derby was left almost completely unopposed for six months,[37] during which he seized more towns, including Montségur, La Réole and Aiguillon and greatly increased English territory and influence in south west France.[38]

Local morale, and more importantly prestige in the border region, had decidedly swung England's way following this conflict, providing an influx of taxes and recruits for the English armies. The region had been in a state of flux for centuries and many local lords served whichever country was stronger, regardless of national ties. With this success, the English had established a regional dominance which in some respects would last a hundred years.[39]

Notes

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

Footnotes

- ↑ Rogers 2004, p. 91.

- ↑ Prestwich 2007, p. 394.

- ↑ Harris 1994, p. 8.

- ↑ Crowcroft & Cannon 2015, p. 389.

- ↑ Lacey 2008, p. 122.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, p. 184.

- ↑ Fowler 1961, pp. 139–40.

- 1 2 Rogers 2004, p. 95.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 273, 275.

- 1 2 3 4 5 DeVries 2006, p. 189.

- ↑ Prestwich 2007, p. 314.

- ↑ Ormrod 2004.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, p. 455.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 455–57.

- ↑ Rogers 2004, p. 94.

- ↑ Gribit 2016, p. 61.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 457–58.

- ↑ Lucas 1929, pp. 519–24.

- ↑ Prestwich 2007, p. 315.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 461–63.

- 1 2 Burne 1999, p. 102.

- ↑ Rogers 2004, p. 97.

- ↑ Rogers 2004, p. 96.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 464–65.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 463–64.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, p. 466.

- ↑ Burne 1999, pp. 104–05.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 465–67.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 467–68.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wagner 2006.

- ↑ Burne 1999, p. 105.

- 1 2 Burne 1999, p. 107.

- 1 2 Sumption 1990, p. 470.

- ↑ Burne 1999, p. 111.

- 1 2 Sumption 1990, p. 469.

- ↑ Burne 1999, p. 112.

- ↑ Fowler 1961, pp. 197–98.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, pp. 474–80.

- ↑ Burne 1999, p. 113.

References

- Burne, Alfred (1999). The Crecy War. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1840222104.

- Crowcroft, Robert; Cannon, John (2015). "Gascony". The Oxford Companion to British History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0199677832.

- DeVries, Kelly (2006). Infantry warfare in the early fourteenth century : discipline, tactics, and technology. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, NY, USA: Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851155715.

- Fowler, Kenneth (1961). Henry of Grosmont, First Duke of Lancaster, 1310–1361 (PDF) (Thesis). Leeds: University of Leeds.

- Gribit, Nicholas (2016). Henry of Lancaster's Expedition to Aquitaine 1345–46. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1783271177.

- Harris, Robin (1994). Valois Guyenne. Royal Historical Society Studies in History. 71. London: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-86193-226-9.

- Lacey, Robert (2008). Great tales from English History. London: Folio Society. OCLC 261939337.

- Lucas, Henry S. (1929). The Low Countries and the Hundred Years' War: 1326–1347. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. OCLC 960872598.

- Ormrod, W. M. (2004). "Henry of Lancaster, first duke of Lancaster (c.1310–1361)". In Cannadine, David. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198736431.

- Prestwich, M. (2007-09-13). J.M. Roberts, ed. Plantagenet England 1225–1360. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922687-0.

- Rogers, Clifford (2004). "The Bergerac Campaign (1345) and the Generalship of Henry of Lancaster". Journal of Medieval Military History. II. ISBN 9781843830405. ISSN 0961-7582.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1990). Trial by Battle. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571200955.

- Wagner, John A. (2006). "Auberoche, Battle of (1345)". Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Greenwood. pp. 35–36. ISBN 9780313327360.