Siege of Calais (1349)

| Siege of Calais | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Edwardian phase of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

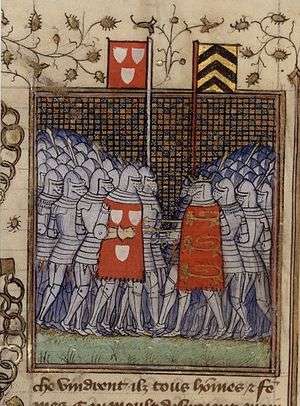

Geoffrey de Charny (left) and King Edward III of England (right) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| at least 900 | 5,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | At least 400 | ||||||

The 1349 siege of Calais was an incident during the Hundred Years' War when a French army under Geoffrey de Charny attempted to bribe an officer of the garrison of English-occupied Calais to open a gate for them, in the early morning of either 31 December 1349 or 2 January 1350. The English had been forewarned by the officer in question, Amerigo of Pavia, and their king, Edward III, personally led his household knights and the Calais garrison in a surprise counter attack. The French were routed by this smaller force, with significant losses and all of their leaders captured.

Later that day Edward III dined with the highest ranking captives, treating them with royal courtesy except for de Charny, whom he taunted with having abandoned his chivalric principles by both fighting during a truce and by attempting to purchase his way into Calais rather than fight. As De Charny was considered a paragon of knightly behaviour and was the author of several books on chivalry the accusations struck deep. They were frequently repeated in subsequent English propaganda. Two years later, having ransomed himself from English captivity, de Charny was placed in charge of a French army on the Calais front. He used it to storm the small fortification commanded by Amerigo, who was taken captive to Saint-Omer and publicly tortured to death.

Background

Since the Norman Conquest of 1066, English monarchs had held titles and lands within France, the possession of which made them vassals to the kings of France. The status of the English king's French fiefs was a major source of conflict between the monarchies throughout the Middle Ages. French monarchs systematically sought to check the growth of English power, stripping away lands as the opportunity arose.[1] Over the centuries, English holdings in France had varied in size, but by 1337 only Gascony (and Ponthieu) were left.[2] Following a series of disagreements between Philip VI of France and Edward III of England, on 24 May 1337, Philip's Great Council in Paris agreed that the Duchy of Aquitaine, effectively Gascony, should be taken back into Philip's hands on the grounds that Edward was in breach of his obligations as a vassal. This marked the start of the Hundred Years' War, which was to last one hundred and sixteen years.[3]

After nine years of inconclusive but expensive warfare, Edward III landed with an army in northern Normandy in July 1346. His army then undertook a devastating chevauchée through Normandy, including the capture and sack of Caen. On 26 August the French army of Philip VI was defeated with heavy loss at the Battle of Crécy. Edward needed a defensible port where his army could regroup and be resupplied from the sea. The Channel port of Calais suited this purpose ideally. Calais was highly defensible: it boasted a double moat, substantial city walls, and its citadel in the north-west corner had its own moat and additional fortifications. It would provide a secure entrepôt into France for English armies; in 1340 Edward had to fight a French fleet larger than his in order to gain access to the port of Sluys and disembark his army. The port could be easily resupplied by sea and defended by land. Edward's army laid siege in September 1346. Philip VI failed to relieve the town, and the starving defenders surrendered on 3 August 1347.[4][5] It was the only large town successfully besieged by either side during the first thirty years of the Hundred Years' War.[6][7] In November 1348 the Truce of Calais was agreed between the English and French kings. In May 1349 it was extended for twelve months.[8]

Prelude

Calais was vital to England's effort against the French for the rest of the war, it being all but impossible to land a significant force other than at a friendly port. It also allowed the accumulation of supplies and materiel prior to a campaign. A ring of substantial fortifications defending the approaches to Calais were rapidly constructed, marking the boundary of an area known as the Pale of Calais. The town had an extremely large standing garrison of 1,400 men, virtually a small army, under the overall command of the Captain of Calais. They had numerous deputies and specialist under-officers. These included Amerigo of Pavia,[note 1] Calais' galley master; galleys were the specialist warships of the day.[9]

Geoffrey de Charny, a well known Burgundian knight in French service, had spent much of 1348 and 1349 in Picardy; by some accounts he had been appointed governor of Saint-Omer.[10] Amerigo had previously served the French, and de Charny approached him to betray Calais in exchange for a bribe. The truce facilitated contact and de Charny reasoned that as a commoner by birth Amerigo would be more susceptible to avarice and as a non-Englishman he would have fewer scruples regarding treachery.[11] Late in 1349 de Charny came to an agreement with him to deliver up Calais in exchange for 20,000 écus (approximately £3,500,000 in 2018 terms[note 2]). However, Amerigo reported the plan to Edward III, on Christmas Eve at Havering near London. Edward responded rapidly, gathering what troops he could and sailing for Calais. De Charny meanwhile gathered a large force, some 5,500 men including most of the nobility of north east France, at Saint-Omer 25 miles (40 km) from Calais.[12][13]

Battle

De Charny's force marched for Calais on the evening of 1 January 1350.[note 3] Long before dawn they approached the town's western gate tower. The gate was open, and Amerigo emerged to greet them. He exchanged his son for the first installment of his bribe and led an advance party of the French into the gatehouse. Shortly a French standard was unfurled atop a tower of the gatehouse and more French crossed the drawbridge over the moat. The drawbridge was drawn up (or possibly broken[14]) behind them, a portcullis fell in front of them and sixty English knights surrounded them. All of the French were captured. [15][16][note 4]

With a cry of "Betrayed" half of de Charny's force fled. He hastily organised the balance into a defensive formation. Edward III, in unmarked armour, led his household troops, supported by 250 archers of the garrison, from the town's southern gate and attacked the French on their right flank. Shortly after, Edward's eldest son the Black Prince, who had led the rest of the garrison out of the north gate and along the beach, attacked their left flank. The King and his son were in the fore of the fighting.[17] The French, who even allowing for their deserters still greatly outnumbered the English, broke. More than 200 men-at-arms were killed in the fighting, along with a greater but unrecorded number of lesser Frenchman. Thirty French knights were taken prisoner; socially inferior combatants were, as was usual,[18] not offered the opportunity to surrender. To these can be added an unknown number of fugitives who drowned, weighed down by their armour as they fled in the dark through the extensive marshes surrounding Calais. As no Englishman of note was killed English casualties are not recorded, but they are thought to have been very light.[15][16]

Among the English nobility involved were Earl Suffolk, Lord Stafford, Lord John Mountecute, Lord John Beauchamp, Lord Berkeley, and Lord de la Waae.[19] Among the French captured was de Charny, with a serious head wound, and Eustace de Ribeaumont and Oudart de Renti; the three leading French commanders in Picardy.[20]

Aftermath

.jpg)

Knightly prisoners were considered the personal property of their captors, who would ransom them for large sums, with a share going to their liege lord. As he had fought in the front rank, Edward claimed many of the prisoners as his own, including de Charny, whose captor he rewarded with a gratuity of 100 marks (approximately £60,000 in 2018 terms).[21] That evening Edward invited the higher ranking of the captives to dine with him, revealing that he had fought them incognito. He made pleasant conversation with all but de Charny, whom he taunted with having abandoned his chivalric principles by both fighting during a truce and by attempting to purchase his way into Calais rather than fight. The detailed defences of de Charny's actions later published suggest that the charges had merit by the standards of the time.[22] De Charny was considered a paragon of knightly behaviour and was the author of several books on chivalry. He was also the keeper of the oriflamme, the French royal battle banner; the requirements of the office included being "a knight noble in intention and deed... virtuous... and chivalrous..."[23] The accusations struck deep and were astute blows in the active propaganda war between the two countries. The whole affair was so embarrassing that French participants were said to have "maintained a tight lipped silence" regarding their roles in it.[20]

De Ribeaumont was promptly released on parole, so that Philip VI should have a first hand account of the debacle his enterprise had ended in, and should hear first hand Edward III's comments to de Charny; de Ribeaumont later voluntarily travelled to England to surrender himself until his ransom was paid. Most of the prisoners were paroled on a promise not to fight until they had redeemed themselves. De Charny had to wait eighteen months until his ransom was paid in full. The amount was not known, but King John II, Philip VI's successor after his death during de Charny's imprisonment, made a partial contribution of 12,000 écus (approximately £1,500,000 in 2018 terms).[24] Amerigo was allowed to keep the installment of his bribe he had received in advance. Shortly after he returned to Italy and went on a pilgrimage to Rome. His hostaged son was carried off into French captivity in the nearby town of Guînes; his further fate is not known.[20]

De Chanry's revenge

In January 1352 a band of English adventurers seized the small town of Guînes, 6 miles (9.7 km) south of Calais, which had an extremely strong keep, by a midnight escalade. The possession of Guînes went a long way to securing Calais against any future surprise assaults.[25] The French were furious, the acting-commander was drawn and quartered for dereliction of duty at de Charny's behest,[26] and a strong protest sent to Edward III. Who was thereby put in a difficult position; a truce was still in place and this was a flagrant breach of it. Retaining Guînes would mean a loss of honour and a resumption of open warfare, for which he was unprepared. He ordered the English occupants to hand it back. As it happened, the English Parliament was scheduled to assemble the following week. After fiery, warmongering speeches from members of the King's Council it voted three years of war taxes. By the end of January the Captain of Calais had fresh orders: to take over the garrisoning of Guines in the King's name; the war resumed.[25]

The English started strengthening the defences of Calais by the construction of bastides (keeps or towers) at strategic points. With full scale war raging Amerigo was back in English service. Clearly he deserved a position of responsibility, equally clearly he was not going to be assigned to anywhere where its betrayal would be a devastating blow.[24] He was placed in charge of a newly constructed bastide at Fretun, 3 miles (4.8 km) south west of Calais.[27]

The main French effort of this round of fighting was against Guînes. Geoffrey de Charny was put in charge of all French forces in the north east.[24] He assembled an army of 4,500 men, against the English garrison of 115. He reoccupied the town, but in spite of fighting described as "savage"[28] he failed to take the keep. In July the Calais garrison launched a surprise night attack on de Charny's army, killing many Frenchmen and destroying their siege works and de Charny abandoned the siege.[29] Before disbanding his army he marched with it on Fretun and launched a surprise attack during the night of 24–25 July. Assailed by an entire French army the night watch fled.[27] According to one account Amerigo was found still in bed, with his newly acquired English mistress.[24][30] De Charny took him to Saint-Omer, where he disbanded his army. Before they departed they gathered, together with the populace from miles around, to witness Amerigo being tortured to death with hot irons, quartered with a meat axe and his body parts displayed above the town gates.[31][27]

Notes

- ↑ According to Preswich, p. 319; referred to as Aimeric by Sumption, p. 23, 60; Aymery according to Froissart; Aimery in Kaeuper and Kennedy, p. 10. There are other variations.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ↑ Other sources give 30 December 1349.

- ↑ The chroniclers of the time give conflicting accounts of the details. Kaeuper and Kennedy, p.11, provide a summary of these.

Footnotes

- ↑ Prestwich 2007, p. 394.

- ↑ Harris 1994, p. 8.

- ↑ Sumption 1990, p. 184.

- ↑ Jaques 2007, p. 184.

- ↑ Burne 1999, pp. 144–47, 1828–3, 204–05.

- ↑ Sumption 1999, p. 392.

- ↑ Rogers 2004, pp. 108–09.

- ↑ Sumption 1999, p. 49.

- ↑ Sumption 1999, pp. 19–21, 23.

- ↑ Burne 1999, pp. 225–26.

- ↑ Kaeuper & Kennedy 1996, p. 10.

- ↑ Prestwich 2007, p. 319.

- ↑ Sumption 1999, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Burne 1999, p. 226.

- 1 2 Sumption 1999, pp. 61–62.

- 1 2 Kaeuper & Kennedy 1996, p. 11.

- ↑ Burne 1999, pp. 226–27.

- ↑ King 2002, pp. 269–70.

- ↑ Froissart 1844, pp. 192–5.

- 1 2 3 Sumption 1999, p. 62.

- ↑ Kaeuper & Kennedy 1996, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Kaeuper & Kennedy 1996, p. 12.

- ↑ Contamine 1973, p. 225, n. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Kaeuper & Kennedy 1996, p. 13.

- 1 2 Sumption 1999, pp. 88–90.

- ↑ Kaeuper & Kennedy 1996, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Sumption 1999, p. 93.

- ↑ Sumption 1999, p. 92.

- ↑ Sumption 1999, pp. 91–93.

- ↑ Froissart 1844, pp. 194–5.

- ↑ Kaeuper & Kennedy 1996, pp. 13–15.

References

- Burne, Alfred (1999). The Crecy War. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1840222104.

- Contamine, Philippe (1973). "L'Oriflamme de Saint Denis". Annales (in French). 31 (6): 1170–1171. OCLC 179713536.

- Froissart, John (1844). The Chronicles of England, France and Spain. London: William Smith. OCLC 91958290.

- Harris, Robin (1994). Valois Guyenne. Royal Historical Society Studies in History. 71. London: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-86193-226-9.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33537-2.

- King, Andy (2002). "According to the Custom Used in French and Scottish Wars: Prisoners and Casualties on the Scottish Marches in the Fourteenth Century". Journal of Medieval History. 28. ISSN 0304-4181.

- Kaeuper, Richard W.; Kennedy, Elspeth (1996). The Book of Chivalry of Geoffroi de Charny: Text, Context and Translation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812215793.

- Prestwich, M. (2007-09-13). J.M. Roberts, ed. Plantagenet England 1225–1360. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922687-0.

- Rogers, Clifford (2004). Bachrach, Bernard S; DeVries, Kelly; Rogers, Clifford J, eds. The Bergerac Campaign (1345) and the Generalship of Henry of Lancaster. Journal of Medieval Military History. II. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843830405. ISSN 0961-7582.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1990). Trial by Battle. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571200955.

- Sumption, Jonathon (1999). Trial by Fire. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-13896-8.