Bastet

| Bastet | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

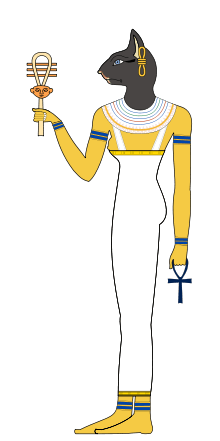

Bastet in her later form as a cat-headed woman. | |||||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

| ||||

| Major cult center | Bubastis | ||||

| Symbol | lioness, cat, the sistrum | ||||

| Consort | Ra | ||||

| Offspring | Maahes | ||||

Bastet or Bast (Ancient Egyptian: bꜣstjt "She of the Ointment Jar", Coptic: Ⲟⲩⲃⲁⲥⲧⲉ[1] /ubastə/) was a goddess of ancient Egyptian religion, worshiped as early as the Second Dynasty (2890 BCE). As Bast, she was the goddess of warfare in Lower Egypt, the Nile Delta, before the unification of the cultures of ancient Egypt. Her name is also translated as B'sst, Baast, Ubaste, and Baset.[2] In ancient Greek religion, she is also known as Ailuros (Koine Greek: αἴλουρος "cat").

The uniting Egyptian cultures had deities that shared similar roles, and usually the same imagery. In Upper Egypt, Sekhmet was the parallel warrior lioness deity. Often similar deities merged into one with the unification, but this did not occur with those deities having particularly strong roots in their cultures. Instead, they began to diverge. During the Twenty-second Dynasty (c. 945–715 BCE) Bast had transformed from a lioness warrior deity into a major protector deity, represented as a cat.[3] Bastet is the name most commonly associated with this later identity, and used by scholars today to refer to this deity. Bastet is also the protector of cats.

Name

Bastet, the form of the name that is most commonly adopted by Egyptologists today because of its use in later dynasties, is a modern convention offering one possible reconstruction. In early Egyptian, her name appears to have been bꜣstt. In Egyptian writing, the second t marks a feminine ending, but was not usually pronounced, and the aleph ꜣ (![]()

During later dynasties, the deity remained, but was assigned a lesser role in the pantheon by bearing the name Bastet. This happened after Thebes became the capital of ancient Egypt, during the Eighteenth Dynasty. As they rose to great power the priests of the temple of Amun, dedicated to the primary local deity, advanced the stature of their titular deity to national prominence (Amun-Ra) and shifted the relative stature of others in the Egyptian pantheon. Diminishing her status, they began referring to the deity with the added suffix, as Bastet, and their use of the new name was well-documented (thereby becoming very familiar to modern researchers). By the Twenty-second Dynasty the transition had occurred in all regions.

What the name of the goddess means, remains uncertain.[4] One recent suggestion by Stephen Quirke (Ancient Egyptian Religion) explains it as meaning, "She of the ointment jar". This ties in with the observation that her name was written with the hieroglyph for ointment jar (bꜣs) and that she was associated with protective ointments, among other things.[4] The name of the material known as alabaster might, through Greek, come from the name of the goddess. This association would have come about much later than when the goddess was a protective lioness goddess, however, and is useful only in deciphering the origin of the term, alabaster.

Role in ancient Egypt

Bast was originally a fierce lioness warrior goddess of the sun throughout most of ancient Egyptian history, but later she was changed into the cat goddess that is familiar today, becoming Bastet. Even later, Greeks occupying ancient Egypt toward the end of its civilization changed her into a goddess of the moon.

As protector of Lower Egypt, Bast, she was seen as defender of the pharaoh, and consequently of the later chief male deity, Ra. Along with the other lioness goddesses, she would occasionally be depicted as the embodiment of the Eye of Ra. She has been depicted as fighting the evil snake named Apep, an enemy of Ra.[5]

Images of Bastet were often created from alabaster. The goddess was sometimes depicted holding a ceremonial sistrum in one hand and an aegis in the other—the aegis usually resembling a collar or gorget embellished with a lioness head.

Her name became associated with the lavish jars in which Egyptians stored their ointment used as perfume. Bastet thus gradually became regarded as the goddess of perfumes, earning the title of perfumed protector. In connection with this, when Anubis became the god of embalming, Bastet came to be regarded as his wife for a short period of time. Bastet was also depicted as the goddess of protection against contagious diseases and evil spirits.[5]

Religious Sect Center

Bast was a local deity whose religious sect was centered in the city of Bubastis, which lay in the Nile Delta near what is known as Zagazig today.[6][7] The town, known in Egyptian as pr-bꜣstt (also transliterated as Per-Bast), carries her name, literally meaning House of Bast. It was known in Greek as Boubastis (Βούβαστις) and translated into Hebrew as Pî-beset, spelled without the initial t sound of the last syllable.[4] In the biblical Book of Ezekiel 30:17, the town appears in the Hebrew form Pibeseth.[6]

History

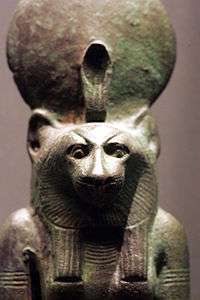

Bast first appears in the third millennium BC, where she is depicted as either a fierce lioness or a woman with the head of a lioness.[6] The lioness was considered the fiercest hunter among the animals in Africa, hunting in co-operative groups of related females, and became the representation of the war goddess and protector in both Egypts that would unite throughout the history of ancient Egypt, with Sekhmet being a similar lioness war deity of Upper Egypt.

The fierce lion god Maahes was said to be the son of Bast.

Scribes of the New Kingdom and later eras began referring to her with an additional feminine suffix, as Bastet. The name change is thought to have been added to emphasize pronunciation of the ending t sound, which was often left silent. Use of the new name became very familiar to Egyptologists.

Cats in ancient Egypt were revered highly, partly due to their ability to combat vermin such as mice, rats (which threatened key food supplies), and snakes—especially cobras. Cats of royalty were, in some instances, known to be dressed in golden jewelry and were allowed to eat from their owners' plates. Turner and Bateson estimate that during the Twenty-second Dynasty (c. 945–715 BC), Bastet worship changed from being a lioness deity into being predominantly a major cat deity.[3] Because domestic cats tend to be tender and protective of their offspring, Bastet was also regarded as a good mother, and she was sometimes depicted with numerous kittens. Consequently, a woman who wanted children sometimes wore an amulet showing the goddess with kittens, the number of which indicated her own desired number of children.

Greek influences

The native Egyptian rulers were replaced by Greeks during an occupation of Egypt in the Ptolemaic Dynasty that lasted almost 300 years. The Ptolemies adopted many Egyptian beliefs and customs, but always "interpreted" them in relation to their own Greek culture. These associations sought to link the antiquity of Egyptian culture to the newer Greek culture, thereby lending parallel roots and a sense of continuity. Indeed, much confusion occurred with subsequent generations; the identity of Bastet slowly merged among the Greeks during their occupation of Egypt, who sometimes named her Ailuros (Greek for cat), thinking of Bastet as a version of Artemis, their own moon goddess.

Temple

Herodotus, a Greek historian who traveled in Egypt in the fifth century BCE, describes Bastet's temple at some length:[8]

Save for the entrance, it stands on an island; two separate channels approach it from the Nile, and after coming up to the entry of the temple, they run round it on opposite sides; each of them a hundred feet wide, and overshadowed by trees. The temple is in the midst of the city, the whole circuit of which commands a view down into it; for the city's level has been raised, but that of the temple has been left as it was from the first, so that it can be seen into from without. A stone wall, carven with figures, runs round it; within is a grove of very tall trees growing round a great shrine, wherein is the image of the goddess; the temple is a square, each side measuring a furlong. A road, paved with stone, of about three furlongs' length leads to the entrance, running eastward through the market place, towards the temple of Hermes; this road is about 400 feet wide, and bordered by trees reaching to heaven.

The description offered by Herodotus and several Egyptian texts suggest that water surrounded the temple on three (out of four) sides, forming a type of lake known as isheru, not too dissimilar from that surrounding the temple of the mother goddess Mut in Karnak at Thebes.[6] These lakes were typical of temples devoted to a number of lioness goddesses who are said to represent one original goddess, daughter of the Sun-God Ra / Eye of Ra: Bast, Mut, Tefnut, Hathor, and Sakhmet.[6] Each of them had to be appeased by a specific set of rituals.[6] One myth relates that a lioness, fiery and wrathful, was once cooled down by the water of the lake, transformed into a gentle cat, and settled in the temple.[6]

In the temple, some cats were found to have been mummified and buried, many next to their owners. More than 300,000 mummified cats were discovered when Bastet's temple was excavated. The main source of information about the Bastet cult comes from Herodotus who visited Bubastis around 450 BCE after the changes in the religious sect. He equated Bastet with the Greek Goddess Artemis. He wrote extensively about the religious sect. Turner and Bateson suggest that the status of the cat was roughly equivalent to that of the cow in modern India. The death of a cat might leave a family in great mourning and those who could would have them embalmed or buried in cat cemeteries—pointing to the great prevalence of the cult of Bastet. Extensive burials of cat remains were found not only at Bubastis, but also at Beni Hasan and Saqqara. In 1888, a farmer uncovered a plot of many hundreds of thousands of cats in Beni Hasan.[3]

Festival

Herodotus also relates that of the many solemn festivals held in Egypt, the most important and most popular one was that celebrated in Bubastis in honor of the goddess.[9][10] Each year on the day of her festival, the town was said to have attracted some 700,000 visitors, both men and women (but not children), who arrived in numerous crowded ships. The women engaged in music, song, and dance on their way to the place. Great sacrifices were made and prodigious amounts of wine were drunk—more than was the case throughout the year.[11] This accords well with Egyptian sources which prescribe that lioness goddesses are to be appeased with the "feasts of drunkenness".[4] However, a festival of Bastet was known to be celebrated already in the New Kingdom at Bubastis. The block statue from the eighteenth dynasty (c. 1380 BC) of Nefer-ka, the wab-priest of Sekhmet,[12] provides written evidence for this. The inscription suggests that the king (Amenhotep III) was personally present at the event and had great offerings made to the deity.

In popular culture

See also

- Sekhmet

- Other (non-Iranian) variants of Lion and Sun

- Felidae – Cat groups

- Feline – Domestic cat

- Cats in ancient Egypt

References

- Herodotus, ed. H. Stein (et al.) and tr. AD Godley (1920), Herodotus 1. Books 1 and 2. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts

- E. Bernhauer, "Block Statue of Nefer-ka", in: M. I. Bakr, H. Brandl, Faye Kalloniatis (eds.): Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. Berlin 2010, pp. 176–179 ISBN 978-3-00-033509-9.

- Velde, Herman te (1999). "Bastet". In Karel van der Toorn; Bob Becking; Pieter W. van der Horst. Dictionary of Demons and Deities in the Bible (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Academic. pp. 164–5. ISBN 90-04-11119-0.

- Serpell, James A. "Domestication and History of the Cat". In Dennis C. Turner; Paul Patrick Gordon Bateson. The Domestic Cat: the Biology of its Behaviour. pp. 177–192.

- ↑ "Coptic Dictionary Online". corpling.uis.georgetown.edu.

- ↑ Badawi, Cherine. Footprint Egypt. Footprint Travel Guides, 2004.

- 1 2 3 Serpell, "Domestication and History of the Cat", p. 184.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Te Velde, "Bastet", p. 165.

- 1 2 Shira. "The Goddesses of Ancient Egypt". Retrieved 2018-03-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Te Velde, "Bastet", p. 164.

- ↑ Bastet Archived July 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Egyptian Museum

- ↑ Herodotus, Book 2, chapter 138.

- ↑ Herodotus, Book 2, chapter 59.

- ↑ Herodotus, Book 2, chapter 137.

- ↑ Herodotus, Book 2, chapter 60.

- ↑ "restoration". project-min.de. Retrieved 2018-03-19.

Further reading

- Malek, Jaromir (1993). The Cat in Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press.

- Otto, Eberhard (1972–1992). "Bastet". In W. Helck; et al. Lexicon der Ägyptologie. 1. Wiesbaden. pp. 628–30.

- Quaegebeur, J. (1991). "Le culte de Boubastis - Bastet en Egypte gréco-romaine". In L. Delvaux and E. Warmenbol. Les divins chat d'Egypte. Leuven. pp. 117–27.

- Quirke, Stephen (1992). Ancient Egyptian Religion. London: British Museum Press.

- Bakr, Mohamed I. & Brandl, Helmut (2010). "Bubastis and the Temple of Bastet". In M. I. Bakr; H. Brandl & F. Kalloniatis. Egyptian Antiquities from Kufur Nigm and Bubastis. Cairo/Berlin. pp. 27–36. ISBN 978-3-00-033509-9

- Bernhauer, Edith (2014). "Stela Fragment (of Bastet)". In M. I. Bakr; H. Brandl; F. Kalloniatis. Egyptian Antiquities from the Eastern Nile Delta. Cairo/Berlin. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-3-00-045318-2

External links

- "All About Bast" — Comprehensive essay by S.D. Cass on per-Bast.org

- "Temple to cat god found in Egypt", BBC News