Cats in ancient Egypt

.jpg)

Cats in ancient Egypt were mummified and buried in large quantities, hence held a special place in the culture of Ancient Egypt. Several deities were depicted and sculptured with cat-like heads such as Mafdet, Bastet and Sekhmet, representing justice, fertility and power.[1] The deity Mut has also been depicted as a cat and in the company of a cat.[2]

Cats were praised for killing poisonous snakes and protecting the Pharaoh since at least the First Dynasty of Egypt. Skeletal remains of cats were found among funerary goods dating to the 12th Dynasty. The protective function of cats is indicated in the Book of the Dead, where a cat represents Ra and the benefits of the sun for life on Earth. Cat-shaped decorations used during the New Kingdom of Egypt indicate that the cat cult became more popular in daily life. Cats were depicted in association with the name of Bastet.[3]

In the late 1880s, more than 200,000 mummified animals, most of them cats, were found in the cemetery of Beni Hasan in central Egypt.[4] Among the mummified animals excavated in Gizeh, the African wildcat is the most common cat followed by the jungle cat.[5] In view of the huge amount of cat mummies found in Egypt, the cat cult was certainly important for the country's economy, as it required breeding of cats and a trading network for the supply of food, oils and resins for embalming them.[6]

History

.jpg)

Mafdet was the first known cat-headed deity in ancient Egypt. During the First Dynasty 2920–2770 BC, she was regarded as protector of the Pharaoh's chambers against snakes, scorpions and evil. She was often also depicted with a head of a leopard.[7][8] She was in particular prominent during the reign of Den.[9]

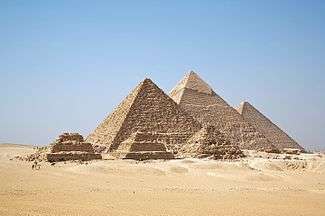

The deity Bastet is known from at least the Second Dynasty 2890 BC onwards. At the time, she was depicted with a lion head. Seals and stone vessels with her name were found in the tombs of the pharaohs Khafra and Nyuserre Ini, indicating that she was regarded as protector since the mid 30th century BC during the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties.[10] A wall painting in the Fifth Dynasty’s burial ground at Saqqara shows a small cat with a collar, suggesting that tamed wildcats were kept in the pharaonic quarters by the 26th century BC.[11]

Amulets with cat heads came into fashion during the 11th Dynasty.[3]

Flinders Petrie excavated 17 cat skeletons in a tomb at the necropolis Umm El Qa'ab dating to the 12th Dynasty 1991–1783 BC. Next to the skeletons stood small pots that are thought to have contained milk for the cats.[2]

From the 22nd Dynasty at around the mid 950s BC onwards, the deity Bastet and her temple in the city of Bubastis became popular. She is now shown only with a small cat head.[1][10] Cat statues and statuettes from this period exist in diverse sizes and materials, including solid and hollow cast bronze, alabaster and faïence.[12][13]

By the end of the 10th century BC, domestic cats had become popular. When they died, they were embalmed, coffined and buried in cat cemetries.[14] The domestic cat was regarded as living incarnation of Bastet who protects the household against granivores, and the lion-headed deity Sekhmet was worshipped as protector of Egypt.[15] Mummifying animals grew in popularity during the Late Period of ancient Egypt from 664 BC onwards. Mummies were used for votive offerings to the associated deity, mostly during festivals or by pilgrims.[6] Catacombs from the New Kingdom period in the Bubastis, Saqqara and Beni Hasan necropoli were reused as cemeteries for mummies offered to Bastet.[16]

As described by Diodorus Siculus, killing a cat was regarded a severe crime. In the years between 60 and 56 BC, outraged people lynched a Roman for killing a cat, although pharaoh Ptolemy XII Auletes tried to intervene.[17]

Cats and religion were disassociated from 30 AD onwards, when Egypt became a Roman province.[1] A series of decrees and edicts issued by Roman Emperors in the 4th and 5th centuries AD gradually curtailed the practise of paganism and pagan rituals in Egypt. Pagan temples were impounded and sacrifices prohibited by 380 AD. Three edicts issued between 391 and 392 prohibited pagan rituals and burial ceremonies at all cult sites. Death penalty for offenders was introduced in 395, and destruction of pagan temples decreed in 399. By 415, the Christian church received all property that was formerly dedicated to paganism. Pagans were exiled by 423, and crosses replaced pagan symbols following a decree from 435.[18]

Excavations

In 1890, William Martin Conway wrote about excavations in Speos Artemidos near Beni Hasan: "The plundering of the cemetery was a sight to see, but one had to stand well windward. The village children came from day to day and provided themselves with the most attractive mummies they could find. These they took down the river bank to sell for the smallest coin to passing travelers. The path became strewn with mummy cloth and bits of cats' skulls and bones and fur in horrid positions, and the wind blew the fragments about and carried the stink afar."[19][20] In 1890, a shipment of thousands of animal mummies reached Liverpool. Most of them were cat mummies. A large part was sold as fertiliser, a small part was purchased by the zoological museum of the city's university college.[4]

In 1907, the British Museum received a collection of 192 mummified cats and 11 small carnivores excavated at Gizeh. The mummies probably date to between 600 and 200 BC.[5] Two of these cat mummies were radiographed in 1980. The analysis revealed that they were deliberately strangulated before they reached the age of two years. They were probably used to supply the demand for mummified cats as votive offerings.[21]

Excavations in the Bubasteum area at Saqqara during the 1990s yielded 184 cat mummies, 11 packets with a few cat bones and 84 packets containing mud, clay and pebbles. Radiographic examination showed that mostly young cats were mummified; most cats died of skull fractures and had dislocated spinal bones, indicating that they were beaten to death. In this site, the tomb of Tutankhamun's wet nurse Maia was discovered in 1996, which contained cat mummies next to human mummies.[16] In 2001, the skeleton of a male lion was found in this tomb that also showed signs of mummification.[22] It was about nine years old, probably lived in captivity for many years and showed signs of malnutrition. It had probably lived and died in the Ptolemaic period.[23]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cats in Ancient Egypt. |

References

- 1 2 3 Malek, J. (1997). The cat in ancient Egypt. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- 1 2 Te Velde, H. (1982). "The cat as sacred animal of the goddess Mut" (PDF). In Van Voss, H., Hoens, D.J., Van de Plas, A., Mussies, G. and Te Velde, H. Studies in Egyptian Religion dedicated to Professor Jan Zandee. Leiden: Brill. pp. 127−137. ISBN 978-90-04-37862-9.

- 1 2 Langton, N. and Langton, M.B. (1940). The cat in ancient Egypt, illustrated from the collection of cat and other Egyptian figures formed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 Herdman, W. A. (1890). "Notes on some mummy cats , &co., from Egypt". Proceedings and transactions of the Liverpool Biological Society. 4: 95–96.

- 1 2 Morrison-Scott, T.C.S. (1952). "The mummified cats of ancient Egypt" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 121 (4): 861–867.

- 1 2 Ikram, S. (2015). "Speculations on the role of animal cults in the economy of Ancient Egypt" (PDF). In Massiera, M., Mathieu, B., Rouffet, F. Apprivoiser le sauvage / Taming the Wild. Montpellier: Cahiers de l’Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne 11. pp. 211–228.

- ↑ Hornblower, G.D. (1943). "The Divine Cat and the Snake in Egypt". Man (43): 85−87.

- ↑ Westendorf, W. (1968). "Die Pantherkatze Mafdet". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 118 (2): 248−256.

- ↑ Reader, C. (2014). "The Netjerikhet Stela and the Early Dynastic Cult of Ra". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 100 (1): 421−435.

- 1 2 Raffaele, F. (2005). "An unpublished Early Dynastic stone vessel fragment with incised inscription naming the goddess Bastet". Cahiers Caribéens d’Egyptologie (7e8): 27e60.

- ↑ Boettger, C.R. (1958). Die Haustiere Afrikas: ihre Herkunft, Bedeutung und Aussichten bei der weiteren wirtschaftlichen Erschliessung des Kontinents. Jena: VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag.

- ↑ Schorsch, D. (1988). "Technological Examinations of Ancient Egyptian Theriomorphic Hollow Cast Bronzes – Some Case Studies". In Watkins, S.C., Brown, C.E. Conservation of Ancient Egyptian Materials, preprints of the conference organised by the United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, Archaeology Section, held at Bristol, December 15-16. London: UKIC Archaeology Section. pp. 41−50.

- ↑ Hassaan, G.A. (2017). "Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part XXXIX: Statues of Cats, Dogs and Lions" (PDF). International Journal of Emerging Engineering Research and Technology. 5 (2): 36−48.

- ↑ Baldwin, J.A. (1975). "Notes and speculations on the domestication of the cat in Egypt". Anthropos (3/4): 428−448.

- ↑ Engels, D.W. (2001). Classical Cats. The Rise and Fall of the Sacred Cat. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415261627.

- 1 2 Zivie, A. and Lichtenberg, R. (2005). "The Cats of the Goddess Bastet". In Ikram, S. Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press. pp. 106−119.

- ↑ Burton, A. (1973). Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. Leiden: Brill. p. 39. ISBN 978-9004035140.

- ↑ Tomorad, M. (2015). "The end of Ancient Egyptian religion: the prohibition of paganism in Egypt from the middle of the 4th to the middle of the 6th century A.D." (PDF). The Journal of Egyptological Studies. IV: 147−167.

- ↑ Conway, M. (1890). "The Cats of Ancient Egypt". English Illustrated Magazine. 7: 251−254.

- ↑ Conway, M. (1891). "Chapter VII. The Cats of Ancient Egypt". The Dawn of Art in the Ancient World: An Archaeological Sketch. New York: Macmillan and Co. pp. 172−185.

- ↑ Armitage, P.L. and Clutton-Brock, J. (1981). "A radiological and histological investigation into the mummification of cats from Ancient Egypt". Journal of Archaeological Science. 8 (2): 185−196.

- ↑ Callou, C., Samzun, A. and Zivie, A. (2004). "Le lion du Bubasteion à Saqqara (Égypte)". Nature. 427 (6971): 211–212.

- ↑ Callou, C., Lichtenberg, R., Hennet, P., Samzun, A. and Zivie, A. (2011). "Archaeology: a lion found in the Egyptian tomb of Maia". Anthropozoologica. 46 (2): 63–84.

External links

- "Divine Felines: Cats of Ancient Egypt". Museum Exhibition. Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 15 April 2014.