Thoth

| ḏḥwtj Thoth | |

|---|---|

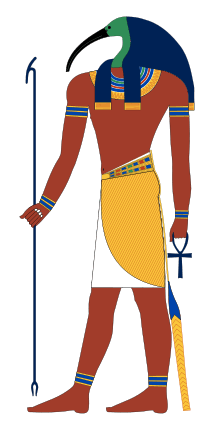

Thoth, in one of his forms as an ibis-headed man | |

| Major cult center | Hermopolis |

| Symbol | Ibis, moon disk, papyrus scroll, reed pens, writing palette, stylus, baboon, scales |

| Consort | Seshat,[1] Maat, Nehmetawy[2] |

| Offspring | Seshat in some accounts |

| Parents | None (self-created); alternatively Neith or Ra or Horus and Hathor |

Thoth (/θoʊθ,

Thoth's chief temple was located in the city of Ancient Egyptian: ḫmnw χaˈmaːnaw, Egyptological pronunciation: "Khemenu", Coptic: Ϣⲙⲟⲩⲛ Shmun,[note 1][4] which was known as Ἑρμοῦ πόλις Hermoû pólis "The City of Hermes", or in Latin as Hermopolis Magna,[5] during the Hellenistic period[6] through the interpretatio graeca that Thoth was Hermes. Later known el-Ashmunein in Egyptian Arabic, it was partially destroyed in 1826.[7]

In Hermopolis, Thoth led "the Ogdoad", a pantheon of eight principal deities, and his spouse was Nehmetawy. He also had numerous shrines within the cities of Abydos, Hesert, Urit, Per-Ab, Rekhui, Ta-ur, Sep, Hat, Pselket, Talmsis, Antcha-Mutet, Bah, Amen-heri-ab, and Ta-kens.[8]

Thoth played many vital and prominent roles in Egyptian mythology, such as maintaining the universe, and being one of the two deities (the other being Maat) who stood on either side of Ra's solar barge.[9] In the later history of ancient Egypt, Thoth became heavily associated with the arbitration of godly disputes,[10] the arts of magic, the system of writing, the development of science,[11] and the judgment of the dead.[12]

Name

Etymology

|

or | ||||||||||

| Common names for Thoth[13] in hieroglyphs |

|---|

The Egyptian pronunciation of ḏḥwty is not fully known, but may be reconstructed as *ḏiḥautī, perhaps pronounced *[t͡ʃʼi.ˈħau.tʰiː] or *[ci.ˈħau.tʰiː]. This reconstruction is based on the Ancient Greek borrowing Thōth (Θώθ [tʰɔːtʰ]) or Theut and the fact that the name was transliterated into Sahidic Coptic variously as ⲑⲟⲟⲩⲧ Thoout, ⲑⲱⲑ Thōth, ⲑⲟⲟⲧ Thoot, ⲑⲁⲩⲧ Thaut, as well as Bohairic Coptic ⲑⲱⲟⲩⲧ Thōout. These spellings reflect known sound changes from earlier Egyptian such as the loss of ḏ palatalization and merger of ḥ with h i.e. initial ḏḥ > th > tʰ.[14] The loss of pre-Coptic final y/j is also common.[15] Following Egyptological convention, which eschews vowel reconstruction, the consonant skeleton ḏḥwty would be rendered "Djehuti" and the god is sometimes found under this name. However, the Greek form "Thoth" is more common.

According to Theodor Hopfner,[16] Thoth's Egyptian name written as ḏḥwty originated from ḏḥw, claimed to be the oldest known name for the ibis, normally written as hbj. The addition of -ty denotes that he possessed the attributes of the ibis.[17] Hence Thoth's name would mean "He who is like the ibis", according to this interpretation.

Further names and spellings

Other forms of the name ḏḥwty using older transcriptions include Jehuti, Jehuty, Tahuti, Tehuti, Zehuti, Techu, or Tetu. Multiple titles for Thoth, similar to the pharaonic titulary, are also known, including A, Sheps, Lord of Khemennu, Asten, Khenti, Mehi, Hab, and A'an.[18]

In addition, Thoth was also known by specific aspects of himself, for instance the moon god Iah-Djehuty (j3ḥ-ḏḥw.ty), representing the Moon for the entire month.[19] The Greeks related Thoth to their god Hermes due to his similar attributes and functions.[20] One of Thoth's titles, "Thrice great" (see Titles) was translated to the Greek τρισμέγιστος (trismégistos), making Hermes Trismegistus.[21]

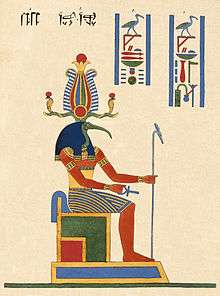

Depictions

Thoth has been depicted in many ways depending on the era and on the aspect the artist wished to convey. Usually, he is depicted in his human form with the head of an ibis.[22] In this form, he can be represented as the reckoner of times and seasons by a headdress of the lunar disk sitting on top of a crescent moon resting on his head. When depicted as a form of Shu or Ankher, he was depicted to be wearing the respective god's headdress. Sometimes he was also seen in art to be wearing the Atef crown or the United Crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt.[17] When not depicted in this common form, he sometimes takes the form of the ibis directly.[22]

He also appears as a dog-faced baboon or a man with the head of a baboon when he is A'an, the god of equilibrium.[23] In the form of A'ah-Djehuty he took a more human-looking form.[24] These forms are all symbolic and are metaphors for Thoth's attributes. The Egyptians did not believe these gods actually looked like humans with animal heads.[25] For example, Ma'at is often depicted with an ostrich feather, "the feather of truth," on her head,[26] or with a feather for a head.[27]

Attributes

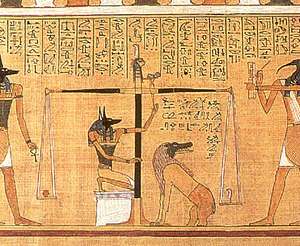

Thoth's roles in Egyptian mythology were many. He served as a mediating power, especially between good and evil, making sure neither had a decisive victory over the other.[28] He also served as scribe of the gods,[29] credited with the invention of writing and Egyptian hieroglyphs.[30] In the underworld, Duat, he appeared as an ape, Aani, the god of equilibrium, who reported when the scales weighing the deceased's heart against the feather, representing the principle of Maat, was exactly even.[31]

The ancient Egyptians regarded Thoth as One, self-begotten, and self-produced.[22] He was the master of both physical and moral (i.e. divine) law,[22] making proper use of Ma'at.[32] He is credited with making the calculations for the establishment of the heavens, stars, Earth,[33] and everything in them.[32] Compare this to how his feminine counterpart, Ma'at was the force which maintained the Universe.[34] He is said to direct the motions of the heavenly bodies. Without his words, the Egyptians believed, the gods would not exist.[29] His power was unlimited in the Underworld and rivalled that of Ra and Osiris.[22]

The Egyptians credited him as the author of all works of science, religion, philosophy, and magic.[35] The Greeks further declared him the inventor of astronomy, astrology, the science of numbers, mathematics, geometry, surveying, medicine, botany, theology, civilized government, the alphabet, reading, writing, and oratory. They further claimed he was the true author of every work of every branch of knowledge, human and divine.[30]

Mythology

Thoth has played a prominent role in many of the Egyptian myths. Displaying his role as arbitrator, he had overseen the three epic battles between good and evil. All three battles are fundamentally the same and belong to different periods. The first battle took place between Ra and Apep, the second between Heru-Bekhutet and Set, and the third between Horus and Set . In each instance, the former god represented order while the latter represented chaos. If one god was seriously injured, Thoth would heal them to prevent either from overtaking the other.

Thoth was also prominent in the Asarian myth, being of great aid to Isis. After Isis/Aset gathered together the pieces of Asar's dismembered body, he gave her the words to resurrect him so she could be impregnated and bring forth Horus. After a battle between Horus and Set in which the latter plucked out Horus' eye, Thoth's counsel provided him the wisdom he needed to recover it. Thoth was the god who always speaks the words that fulfill the wishes of Ra.

This mythology also credits him with the creation of the 365-day calendar. Originally, according to the myth, the year was only 360 days long and Nut was sterile during these days, unable to bear children. Thoth gambled with the Moon for 1/72nd of its light (360/72 = 5), or 5 days, and won. During these 5 days, Nut and Geb gave birth to Ausar (Osiris), Set, Auset (Isis), and Nebt-Het (Nephthys).

History

Thoth was originally a moon god. The moon not only provides light at night, allowing time to still be measured without the sun, but its phases and prominence gave it a significant importance in early astrology/astronomy. The cycles of the moon also organized much of Egyptian society's rituals and events, both civil and religious. Consequently, Thoth gradually became seen as a god of wisdom, magic, and the measurement and regulation of events and of time.[36] He was thus said to be the secretary and counselor of the sun god Ra, and with Ma'at (truth/order) stood next to Ra on the nightly voyage across the sky.

Thoth became credited by the ancient Egyptians as the inventor of writing (hieroglyphs)[37], and was also considered to have been the scribe of the underworld; and the Moon became occasionally considered a separate entity, now that Thoth had less association with it and more with wisdom. For this reason Thoth was universally worshipped by ancient Egyptian scribes. Many scribes had a painting or a picture of Thoth in their "office". Likewise, one of the symbols for scribes was that of the ibis.

In art, Thoth was usually depicted with the head of an ibis, possibly because the Egyptians saw curve of the ibis' beak as a symbol of the crescent moon.[38] Sometimes, he was depicted as a baboon holding up a crescent moon, as the baboon was seen as a nocturnal and intelligent creature. The association with baboons led to him occasionally being said to have as a consort Astennu, one of the (male) baboons at the place of judgment in the underworld. On other occasions, Astennu was said to be Thoth himself.

During the late period of Egyptian history, a cult of Thoth gained prominence due to its main centre, Khmun (Hermopolis Magna), also becoming the capital. Millions of dead ibis were mummified and buried in his honour. The rise of his cult also led to his cult seeking to adjust mythology to give Thoth a greater role.

Thoth was inserted in many tales as the wise counselor and persuader, and his association with learning and measurement led him to be connected with Seshat, the earlier deification of wisdom, who was said to be his daughter, or variably his wife. Thoth's qualities also led to him being identified by the Greeks with their closest matching god Hermes, with whom Thoth was eventually combined as Hermes Trismegistus, also leading to the Greeks' naming Thoth's cult centre as Hermopolis, meaning city of Hermes.

It is also considered that Thoth was the scribe of the gods rather than a messenger. Anpu (or Hermanubis) was viewed as the messenger of the gods, as he travelled in and out of the Underworld and presented himself to the gods and to humans. It is more widely accepted that Thoth was a record keeper, not a divine messenger. In the Papyrus of Ani copy of the Egyptian Book of the Dead the scribe proclaims "I am thy writing palette, O Thoth, and I have brought unto thee thine ink-jar. I am not of those who work iniquity in their secret places; let not evil happen unto me."[39] Chapter XXXb (Budge) of the Book of the Dead is by the oldest tradition said to be the work of Thoth himself.[40]

There was also an Egyptian pharaoh of the Sixteenth dynasty named Djehuty (Thoth) after him, and who reigned for three years.

Artapanus of Alexandria, an Egyptian Jew who lived in the third or second century BC, euhemerized Thoth-Hermes as a historical human being and claimed he was the same person as Moses, based primarily on their shared roles as authors of texts and creators of laws. Artapanus's biography of Moses conflates traditions about Moses and Thoth and invents many details.[41] Many later authors, from late antiquity to the Renaissance, either identified Hermes Trismegistus with Moses or regarded them as contemporaries who expounded similar beliefs.[42]

Modern cultural references

Thoth has been seen as a god of wisdom and has been used in modern literature, especially since the early 20th century when ancient Egyptian ideas were quite popular.

- Aleister Crowley named his Egyptian style Tarot deck "The Book of Thoth", in reference to the theory that Tarot cards were the Egyptian book of Thoth.

- H. P. Lovecraft also used the word "Thoth" as the basis for his god, "Yog-Sothoth", a god of knowledge.[43]

- In Mika Waltari's The Egyptian, the illegitimate son of Sinuhe is named after Thoth, much to the surprise of his father.

- Thoth is mentioned as one of the pantheon in the 1831 issue of The Wicked + The Divine.

- Thoth appears as Mr. Ibis in Neil Gaiman's American Gods.

- The principle mecha in Zone of the Enders is named Jehuty.

- Thoth is a playable character in the battle arena game Smite.

- In the 2016 film Gods of Egypt, Thoth is played by Chadwick Boseman.[44]

- Thoth is the name of a psychically generated entity in the series JoJo's Bizarre Adventure. He manifests in the form of a comic book whose illustrations predict the future.

- Thoth is also a recurring character in The Kane Chronicles book series.

- Thoth is the name of a station monitoring activities and the location of a major battle in the novel Leviathan Wakes

See also

- Eye of Horus

- The Book of Thoth

- The Book of Thoth (Crowley)

- Thout, the first month of the Coptic calendar

Notes

References

- ↑ Wilkison, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, p. 166

- ↑ Bleeker, C. J. (1973). Hathor and Thoth: Two Key Figures of the Ancient Egyptian Religion, pp. 121–123

- ↑ Thutmose III: A New Biography By Eric H Cline, David O'Connor University of Michigan Press (January 5, 2006)p. 127

- ↑ National Geographic Society: Egypt's Nile Valley Supplement Map. (Produced by the Cartographic Division)

- ↑ "Great Hermopolis", for distinction with Lesser Hermopolis, e.g. Stephanus of Byzantium s.v. Ἑρμοῦ πόλις; Ptolemy IV 5. § 60. Antonine Itinerary pp. 154f.

- ↑ National Geographic Society: Egypt's Nile Valley Supplement Map: Western Desert portion. (Produced by the Cartographic Division)

- ↑ Miroslav Verner, Temple of the World: Sanctuaries, Cults, and Mysteries of Ancient Egypt (2013) 149

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Thoth was said to be born from the skull of set also said to be born from the heart of Ra.p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 400)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 405)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 414)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians p. 403)

- ↑ Hieroglyphs verified, in part, in (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 402) and (Collier and Manley p. 161)

- ↑ Allen, James P. (2013-07-11). The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107032460.

- ↑ Allen, James P. (2013-07-11). The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107032460.

- ↑ Hopfner, Theodor, b. 1886. Der tierkult der alten Agypter nach den griechisch-romischen berichten und den wichtigeren denkmalern. Wien, In kommission bei A. Holder, 1913. Call#= 060 VPD v.57

- 1 2 (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 402)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 402–3)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 412–3)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians p. 402)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 415)

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 403)

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 plate between pp. 408–9)

- ↑ Allen, James P. (2000). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, p. 44.

- ↑ Allen, op. cit., p. 115

- ↑ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 416)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 405)

- 1 2 (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 408)

- 1 2 (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 414)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 403)

- 1 2 (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 407)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ↑ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 407–8)

- ↑ (Hall The Hermetic Marriage p. 224)

- ↑ Assmann, Jan, The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, 2001, pp. 80–81

- ↑ Littleton, C.Scott (2002). Mythology. The illustrated anthology of world myth & storytelling. London: Duncan Baird Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 9781903296370.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Richard H., The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, 2003, p. 217

- ↑ The Book of the Dead by E. A. Wallis Budge, 1895, Gramercy, 1999, p. 562, ISBN 0-517-12283-9

- ↑ The Book of the Dead by E. A. Wallis Budge, 1895, Gramercy, 1999, p. 282, ISBN 0-517-12283-9

- ↑ Mussies, Gerald (1982), "The Interpretatio Judaica of Thot-Hermes", in van Voss, Heerma, et al. (eds.) Studies in Egyptian Religion Dedicated to Professor Jan Zandee, pp. 91, 97, 99–100

- ↑ Mussies (1982), pp. 118–120

- ↑ Steadman, John L. (2015-09-01). H. P. Lovecraft and the Black Magickal Tradition: The Master of Horror's Influence on Modern Occultism. Weiser Books. ISBN 9781633410008.

- ↑ Lee, Benjamin (November 13, 2015). "Gods of Egypt posters spark anger with 'whitewashed' cast". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

Bibliography

- Bleeker, Claas Jouco. 1973. Hathor and Thoth: Two Key Figures of the Ancient Egyptian Religion. Studies in the History of Religions 26. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Boylan, Patrick. 1922. Thoth, the Hermes of Egypt: A Study of Some Aspects of Theological Thought in Ancient Egypt. London: Oxford University Press. (Reprinted Chicago: Ares Publishers inc., 1979).

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. Egyptian Religion. Kessinger Publishing, 1900.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The Gods of the Egyptians Volume 1 of 2. New York: Dover Publications, 1969 (original in 1904).

- Jaroslav Černý. 1948. "Thoth as Creator of Languages." Journal of Egyptian Archæology 34:121–122.

- Collier, Mark and Manley, Bill. How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Revised Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Fowden, Garth. 1986. The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Mind. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. (Reprinted Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993). ISBN 0-691-02498-7.

- The Book of Thoth, by Aleister Crowley. (200 signed copies, 1944) Reprinted by Samuel Wiser, Inc 1969, first paperback edition, 1974 (accompanied by The Thoth Tarot Deck, by Aleister Crowley & Lady Fred Harris)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thoth. |

- Stadler, Martin (2012). "Thoth". In Dieleman, Jacco; Wendrich, Willeke. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UC Los Angeles.