Second Council of Nicaea

| Second Council of Nicaea | |

|---|---|

| Date | 787 |

| Accepted by |

Eastern Orthodox Church Roman Catholic Church Old Catholic Church Some Protestant churches |

Previous council |

(Catholic) Third Council of Constantinople (Orthodox) Quinisext Council |

Next council |

(Catholic) Fourth Council of Constantinople (Orthodox) Fourth Council of Constantinople (Eastern Orthodox) |

| Convoked by | Constantine VI and Empress Irene (as regent) |

| President | Patriarch Tarasios of Constantinople, legates of Pope Adrian I |

| Attendance | 350 bishops (including two papal legates) |

| Topics | Iconoclasm |

Documents and statements | veneration of icons approved |

| Chronological list of ecumenical councils | |

| Part of a series on |

| Ecumenical councils of the Catholic Church |

|---|

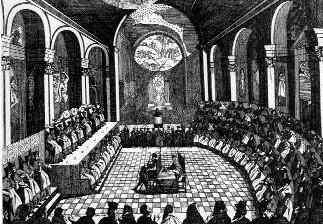

Renaissance depiction of the Council of Trent |

| Antiquity (c. 50 – 451) |

| Early Middle Ages (553–870) |

| High and Late Middle Ages (1122–1517) |

| Modernity (1545–1965) |

|

|

The Second Council of Nicaea is recognized as the last of the first seven ecumenical councils by the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church. In addition, it is also recognized as such by the Old Catholics and others. Protestant opinions on it are varied.

It met in AD 787 in Nicaea (site of the First Council of Nicaea; present-day İznik in Turkey) to restore the use and veneration of icons (or, holy images),[1] which had been suppressed by imperial edict inside the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Leo III (717–741). His son, Constantine V (741–775), had held the Council of Hieria to make the suppression official.

Background

The veneration of icons had been banned by Byzantine Emperor Constantine V and supported by his Council of Hieria (754 AD), which had described itself as the seventh ecumenical council.[2] The Council of Hieria was overturned by the Second Council of Nicaea only 33 years later, and has also been rejected by Catholic and Orthodox churches, since none of the five major patriarchs were represented. The emperor's vigorous enforcement of the ban included persecution of those who venerated icons and monks in general. There were also political overtones to the persecution—images of emperors were still allowed by Constantine, which some opponents saw as an attempt to give wider authority to imperial power than to the saints and bishops.[3] Constantine's iconoclastic tendencies were shared by Constantine's son, Leo IV. After the latter's early death, his widow, Irene of Athens, as regent for her son, began its restoration for personal inclination and political considerations.

In 784 the imperial secretary Patriarch Tarasius was appointed successor to the Patriarch Paul IV—he accepted on the condition that intercommunion with the other churches should be reestablished; that is, that the images should be restored. However, a council, claiming to be ecumenical, had abolished the veneration of icons, so psychologically another ecumenical council was necessary for its restoration.

Pope Adrian I was invited to participate, and gladly accepted, sending an archbishop and an abbot as his legates.

In 786, the council met in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. However, soldiers in collusion with the opposition entered the church, and broke up the assembly.[4] As a result, the government resorted to a stratagem. Under the pretext of a campaign, the iconoclastic bodyguard was sent away from the capital – disarmed and disbanded.

The council was again summoned to meet, this time in Nicaea, since Constantinople was still distrusted. The council assembled on September 24, 787 at the church of Hagia Sophia. It numbered about 350 members; 308 bishops or their representatives signed. Tarasius presided,[5] and seven sessions were held in Nicaea.[6]

Proceedings

First Session (September 24, 787) – Three bishops, Basilius of Ancyra, Theodore of Myra and Theodosius of Amorium begged for pardon for the heresy of iconoclasm.

Second Session (September 26, 787) – Papal legates read the letters of Pope Hadrian I asking for agreement with veneration of images; the bishops of the council answered: "We follow, we receive, we admit".

Third Session (September 28, 787) — Other bishops having made their abjuration, were received into the council.

Fourth Session (October 1, 787) — Proof of the lawfulness of the veneration of icons was drawn from Exodus 25:19 sqq.; Numbers 7:89; Hebrews 9:5 sqq.; Ezekiel 41:18, and Genesis 31:34, but especially from a series of passages of the Church Fathers;[1] the authority of the latter was decisive.

Fifth Session (October 4, 787) – It was claimed that the iconoclast heresy came originally from Jews, Saracens, and Manicheans.

Sixth Session (October 6, 787) – The definition of the pseudo-Seventh council (754) was read and condemned.

Seventh Session (October 13, 787) – The council issued a declaration of faith concerning the veneration of holy images.

It was determined that "As the sacred and life-giving cross is everywhere set up as a symbol, so also should the images of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the holy angels, as well as those of the saints and other pious and holy men be embodied in the manufacture of sacred vessels, tapestries, vestments, etc., and exhibited on the walls of churches, in the homes, and in all conspicuous places, by the roadside and everywhere, to be revered by all who might see them. For the more they are contemplated, the more they move to fervent memory of their prototypes. Therefore, it is proper to accord to them a fervent and reverent adoration, not, however, the veritable worship which, according to our faith, belongs to the Divine Being alone – for the honor accorded to the image passes over to its prototype, and whoever venerate the image venerate in it the reality of what is there represented."

Eighth Session (October 23, 787) – The last session was held in Constantinople at the Magnaura Palace. The Empress Irene and her son were present and they signed the document.

The clear distinction between the adoration offered to God, and that accorded to the images may well be looked upon as a result of the iconoclastic reform. The twenty-two canons[7] drawn up in Constantinople also served ecclesiastical reform. Careful maintenance of the ordinances of the earlier councils, knowledge of the scriptures on the part of the clergy, and care for Christian conduct are required, and the desire for a renewal of ecclesiastical life is awakened.

The council also decreed that every altar should contain a relic, which remains the case in modern Catholic and Orthodox regulations (Canon VII), and made a number of decrees on clerical discipline, especially for monks when mixing with women.

Acceptance of the Council by various Christian bodies

The papal legates voiced their approval of the restoration of the veneration of icons in no uncertain terms, and the patriarch sent a full account of the proceedings of the council to Pope Hadrian I, who had it translated (Pope Anastasius III later replaced the translation with a better one). In the West, the Frankish clergy initially rejected the Council at a synod in 794, and Charlemagne, then King of the Franks, supported the composition of the Libri Carolini in response, which repudiated the teachings of both the Council and the iconoclasts. A copy of the Libri was sent to Pope Hadrian, who responded with a refutation of the Frankish arguments.[8] The Libri would thereafter remain unpublished until the Reformation, and the Council is accepted as the Seventh Ecumenical Council by the Roman Catholic Church.

This council is celebrated in the Eastern Orthodox Church, and Eastern Catholic Churches of Byzantine Rite as "The Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy" each year on the first Sunday of Great Lent—the fast that leads up to Pascha (Easter)—and again on the Sunday closest to October 11 (the Sunday on or after October 8). The former celebration commemorates the council as the culmination of the Church's battles against heresy, while the latter commemorates the council itself.

Many Protestants follow the French reformer John Calvin in rejecting the canons of the council for what they believe was the promotion of idolatry. He rejected the distinction between veneration (douleia, proskynesis) and adoration (latreia) as unbiblical "sophistry" and condemned even the decorative use of images.[9] In subsequent editions of the Institutes he cites an influential Carolingian source, now ascribed to Theodulf of Orleans, which reacts negatively to a poor Latin translation of the council's acts. Calvin does not engage the apologetic arguments of John of Damascus or Theodore the Studite, apparently because he is unaware of them.

Translations of the Acts

There are only a few translations of the above Acts in the modern languages:

- English translation made in 1850 by an Anglican priest, John Mendham; presented in a wide controversy, which in its turn is probably the most extensive and well commented translation of Libri Carolini.

- The Canons and excerpts of the Acts in The Seven Ecumenical Councils of the Undivided Church, translated by Henry R. Percival and edited by Philip Schaff (1901).

- Translation made by Kazan Theological Academy (published from 1873 to 1909) – a seriously corrupted translation of the Acts of the Councils into Russian.[10]

- A relatively new Vatican's translation (2004) into Italian language. Publishers in Vatican mistakenly thought[11] that they made the first translation of the Acts into European languages.[12]

- The new (2016) Russian version of the Acts of the Council is a revised version of the translation made by Kazan Theological Academy, specifying the cases of corruption by the Orthodox translators.[13] There are several dozens of such cases, some of them are critical.

See also

References

- 1 2 Gibbon, p.1693

- ↑ Council of Hieria, Canon 19, "If anyone does not accept this our Holy and Ecumenical Seventh Synod, let him be anathema from the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, and from the seven holy Ecumenical Synods!" http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/icono-cncl754.asp

- ↑ Warren T. Treadgold (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-8047-2630-6. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ↑ Ostrogorsky, p.178.

- ↑ Gibbon, p.1693.

- ↑ Ostrogorsky, p.178

- ↑ "NPNF2-14. The Seven Ecumenical Councils - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org.

- ↑ Hussey, J. M. (1986). The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 49–50.

- ↑ cf. John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion 1.11

- ↑ See: http://www.knigafund.ru/books/12281/read

- ↑ See: N. Tanner, "Atti del Concilio Niceno Secondo Ecumenico Settimo, Tomi I–III, introduzione e traduzione di Pier Giorgio Di Domenico, saggio encomiastico di Crispino Valenziano", in "Gregorianum", N. 86/4, Rome, 2005, p. 928.

- ↑ Roman Catholic Church, Atti del Concilio Niceno Secondo Ecumenico Settimo (Citta del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2004) ISBN 9788820976491

- ↑ ISBN 9785446908912

Sources

- Calvin, John, Institutes of the Christian Religion (1559), translated by Henry Beveridge (1845). Peabody: Hendrickson, 2008.

- Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. New York:Random House Inc., 1995. ISBN 0-679-60148-1

- Ostrogorsky, George. History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick:Rutgers University Press, 1969. ISBN 0-8135-0599-2

- Raab, Clement. The Twenty Ecumenical Councils of the Catholic Church, 1937.

Further reading

- Mendham, John, tr. The seventh general council, the second of Nicaea, held A.D. 787, in which the worship of images was established with copious notes from the "Caroline books", compiled by order of Charlemagne for its confutation, London, W.E. Painter, 1850.

- Concilium Universale Nicaenum Secundum. Concilium actiones I-III, ed. Erich Lambertz (Acta Conciliorum Oecumenicorum 2,3,1), Berlin, New York 2008. ISBN 978-3-11-019002-1 Edition with introduction in the sources.