Attack on Mers-el-Kébir

The Attack on Mers-el-Kébir (3 July 1940) also known as the Battle of Mers-el-Kébir, was part of Operation Catapult. The operation was a British naval attack on French Navy ships at the base at Mers El Kébir on the coast of French Algeria. The bombardment killed 1,297 French servicemen, sank a battleship and damaged five ships, for a British loss of five aircraft shot down and two crewmen killed.

The combined air-and-sea attack was conducted by the Royal Navy after France had signed armistices with Germany and Italy that came into effect on 25 June. Of particular significance to the British were the seven battleships of the Bretagne, Dunkerque and Richelieu classes, the second largest force of capital ships in Europe after the Royal Navy. The British War Cabinet feared already that France would hand the ships to the Kriegsmarine, giving the Axis assistance in the Battle of the Atlantic. Admiral François Darlan, commander of the French Navy, promised the British that the fleet would remain under French control but Winston Churchill and the War Cabinet judged that the fleet was too powerful to risk an Axis take-over.

After the attack at Mers-el-Kébir and the Battle of Dakar, French aircraft raided Gibraltar in retaliation and the Vichy government severed diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom. The attack created much rancour between France and Britain but also demonstrated to the world that Britain intended to fight on.[2] The attack is controversial and the motives of the British are debated. In 1979, P. M. H. Bell wrote that "The times were desperate; invasion seemed imminent; and the British government simply could not afford to risk the Germans seizing control of the French fleet... The predominant British motive was thus dire necessity and self-preservation".

The French thought they were acting honourably in terms of their armistice with Nazi Germany and were convinced they would never turn over their fleet to Germany. Vichy France was created on 10 July 1940, one week after the attack and was seen by the British as a puppet state of the Nazi regime. French grievances festered for years over what they considered a betrayal by their ally. On 27 November 1942, the scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon foiled Operation Anton, a German attempt to capture the fleet.

Background

Franco-German armistice

After the Fall of France in 1940 and the armistice between France and Nazi Germany, the British War Cabinet was apprehensive about the Germans acquiring control of the French navy from the government of Vichy France. The French and German navies combined could alter the balance of power at sea, threatening British imports over the Atlantic and communications with the rest of the British Empire. That the armistice terms at article eight paragraph two stated that the German government "solemnly and firmly declared that it had no intention of making demands regarding the French fleet during the peace negotiations" and that similar terms existed in the armistice with Italy, were considered to be no guarantee of the neutralisation of the French fleet. On 24 June, Darlan assured Winston Churchill against such a possibility.[3] Churchill ordered that a demand be made that the French Navy (Marine nationale) should either join with the Royal Navy or be neutralised in a manner guaranteed to prevent the ships falling into Axis hands.[4]

At Italian suggestion, the armistice terms were amended to permit the French fleet to stay temporarily in North African ports, where they might be seized by Italian troops from Libya. The British made contingency plans to eliminate the French fleet (Operation Catapult) in mid-June, when it was clear that Philippe Pétain was forming a government with a view to signing an armistice and it seemed likely that the French fleet might be seized by the Germans.[5] In a speech to Parliament, Churchill repeated that the Armistice of 22 June 1940 was a betrayal of the Allied agreement not to make a separate peace. Churchill said "What is the value of that? Ask half a dozen countries; what is the value of such a solemn assurance? ... Finally, the armistice could be voided at any time on any pretext of non-observance ..."[6]

The French fleet had seen little fighting during the Battle of France and was mostly intact. By tonnage, about 40 percent was in Toulon, near Marseilles, 40 percent in French North Africa and 20 percent in Britain, Alexandria and the French West Indies. Although Churchill feared the fleet would be put into action, the Axis leaders did not intend to employ a combined Franco-Italian-German force. The German Navy and Benito Mussolini made overtures but Adolf Hitler feared that the French fleet would defect to the British and be used against German submarines in the Atlantic if he tried to take it over. Churchill and Hitler viewed the fleet as a potential threat; the Vichy French leaders used the fleet (and the possibility of its rejoining the Allies) as a bargaining counter against the Germans to keep them out of the Zone libre and French North Africa. The armistice was contingent on the French right to man their vessels and the French Navy Minister, Admiral François Darlan, had ordered the Atlantic fleet to Toulon to demobilise, with orders to scuttle if the Germans tried to take the ships.[7]

British-French negotiations

The British tried to persuade the French authorities in North Africa to continue the war, or alternatively to hand over the fleet to British control. A British admiral visited Oran on 24 June, and on 27 June Duff Cooper, Minister of Information, visited Casablanca.[8] The French Atlantic ports were in German hands, while the British needed to keep the German surface fleet out of the Mediterranean, to confine the Italian fleet to the Mediterranean and to blockade the Vichy ports. The Admiralty was against an attack on the French fleet, since if not enough damage were done to the ships, Vichy France would be provoked into declaring war and the French colonial empire as a result become more hostile to the Free French Forces. Given the need to keep the Atlantic approaches open, and given that the Royal Navy lacked the ships to provide a permanent blockade on the Vichy naval bases in North Africa, the risk of having the Germans or the Italians seize the French capital ships was deemed too great. Because the fleet in Toulon was well guarded by shore artillery, the Royal Navy decided to attack that based in North Africa.[9]

Operation Catapult

Along with French vessels in metropolitan ports, some had sailed to ports in Britain or to Alexandria in Egypt. Operation Catapult was an attempt to take these ships under British control or destroy them, and the French ships in Plymouth and Portsmouth were boarded without warning on the night of 3 July 1940.[10][11] The submarine Surcouf, the largest submarine in the world, had been berthed in Plymouth since June 1940.[12] The crew resisted a boarding party and three Royal Navy personnel, including two officers, were killed along with a French sailor. Other ships captured included the old battleships Paris and Courbet, the destroyers Le Triomphant and Léopard, eight torpedo boats, five submarines and a number of lesser ships. The French squadron in Alexandria (Admiral René-Émile Godfroy) including the battleship Lorraine, heavy cruiser Suffren and three modern light cruisers, was neutralised by local agreement.[13]

Ultimatum

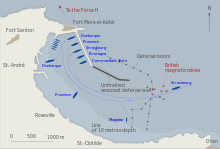

The most powerful group of French warships was at Mers-el-Kébir in French Algeria, consisting of the old battleships Provence and Bretagne, the newer Force de Raid battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg, the seaplane tender Commandant Teste and six destroyers under the command of Admiral Marcel-Bruno Gensoul. Admiral James Somerville of Force H, based in Gibraltar, was ordered to deliver an ultimatum to the French but the British terms were contrary to the German-French armistice terms.[8][lower-alpha 1] Somerville passed the duty of presenting the ultimatum to a French speaker, Captain Cedric Holland, commander of the carrier HMS Ark Royal. Gensoul was affronted that negotiations were not being conducted by a senior officer and sent his lieutenant, Bernard Dufay, which led to much delay and confusion. As negotiations dragged on, it became clear that neither side was likely to give way. Darlan was at home on 3 July and could not be contacted; Gensoul told the French government that the alternatives were internment or battle but omitted the option of sailing to the French West Indies.[8] Removing the fleet to United States waters had formed part of the orders given by Darlan to Gensoul in the event that a foreign power should attempt to seize his ships.[14]

Attack

The British force comprised the battlecruiser HMS Hood, the battleships HMS Valiant and Resolution, the aircraft carrier Ark Royal and an escort of cruisers and destroyers. The British had the advantage of being able to manoeuvre, while the French fleet was anchored in a narrow harbour and its crews did not expect an attack. The main armament of Dunkerque and Strasbourg was grouped on their bows and could not immediately be brought to bear. The British capital ships had 15-inch (381 mm) guns and fired a heavier broadside than the French. On 3 July, before negotiations were formally terminated, British Fairey Swordfish planes escorted by Blackburn Skuas from Ark Royal dropped magnetic mines in the harbour exit. The force was intercepted by French Curtiss H-75 fighters and a Skua was shot down into the sea with the loss of its two crew, the only British fatalities in the action.[15] French warships were ordered from Algiers and Toulon as reinforcements but did not reach Mers-El-Kebir in time to affect the outcome.[8]

A short while later, at 5:54 p.m., Churchill ordered the British ships to open fire against the French ships and the British commenced from 17,500 yd (9.9 mi; 16.0 km).[16] The third British salvo scored hits and caused a magazine explosion aboard Bretagne, which sank with 977 of her crew at 6:09 p.m. After thirty salvoes, the French ships stopped firing; the British force altered course to avoid return fire from the French coastal forts but Provence, Dunkerque and the destroyer Mogador were damaged and run aground by their crews.[17] Strasbourg and four destroyers managed to avoid the magnetic mines and escape to the open sea under attack from a flight of bomb-armed Swordfish from Ark Royal. The French ships responded with anti-aircraft fire and shot down two Swordfish, the crews being rescued by the destroyer HMS Wrestler. As the bombing had little effect, at 6:43 p.m. Somerville ordered his forces to pursue and the light cruisers HMS Arethusa and Enterprise engaged a French destroyer. At 8:20 p.m. Somerville called off the pursuit, feeling that his ships were ill deployed for a night engagement. After another ineffective Swordfish attack at 8:55 p.m., Strasbourg reached Toulon on 4 July.[18]

On 4 July, the British submarine HMS Pandora sank the French aviso (gunboat) Rigault de Genouilly, sailing from Oran, with the loss of 12 of its crew. As the British believed that the damage inflicted on Dunkerque and Provence was not serious, Swordfish aircraft from Ark Royal raided Mers-el-Kébir again on the morning of 8 July. A torpedo hit the patrol boat Terre-Neuve, which was full of depth charges and moored alongside Dunkerque. Terre-Neuve quickly sank and the depth charges went off, causing serious damage to Dunkerque.[19] The last phase of Operation Catapult was another attack on 8 July, by aircraft from the carrier HMS Hermes against the battleship Richelieu at Dakar, which was seriously damaged. The French Air Force (Armée de l'Air) made reprisal raids on Gibraltar, including a half-hearted night attack on 5 July, when many bombs landed in the sea and raids on 24 September by forty aircraft and the next day with more than a hundred bombers.[20][21]

Aftermath

Analysis

Churchill wrote "This was the most hateful decision, the most unnatural and painful in which I have ever been concerned".[22] Relations between Britain and France were severely strained for some time and the Germans enjoyed a propaganda coup. Somerville said that it was "...the biggest political blunder of modern times and will rouse the whole world against us...we all feel thoroughly ashamed...".[23] Although it did rekindle anglophobia in France, the action demonstrated Britain's resolve to continue the war and rallied the British Conservative Party around Churchill (Neville Chamberlain, Churchill's predecessor as prime minister, was still party leader). The British action showed the world that defeat in France had not reduced the determination of the government to fight on and ambassadors in Mediterranean countries reported favourable reactions.[20]

The French ships in Alexandria under the command of Admiral René-Emile Godfroy, including the World War I era battleship Lorraine and four cruisers, were blockaded by the British on 3 July and offered the same terms as at Mers-el-Kébir. After delicate negotiations, conducted on the part of the British by Admiral Andrew Cunningham, Godfroy agreed on 7 July to disarm his fleet and stay in port until the end of the war.[24] Some sailors joined the Free French while others were repatriated to France; Surcouf and the ships at Alexandria went on to be used by the Free French after May 1943. The British attacks on French vessels in port sowed anger among the French towards the British and increased tension between Churchill and Charles de Gaulle, who was recognised by the British as the leader of the Free French Forces on 28 June.[25][26]

According to his principal private secretary Eric Seal, "[Churchill] was convinced that the Americans were impressed by ruthlessness in dealing with a ruthless foe; and in his mind the American reaction to our attack on the French fleet in Oran was of the first importance". On 4 July, Roosevelt told the French ambassador that he would have done the same.[27] De Gaulle's biographer Jean Lacouture blamed the tragedy mainly on miscommunication; had Darlan been in contact on the day or had Somerville possessed a more diplomatic character, a deal might have been done. Lacouture accepted that there was a danger that the French ships might have been captured by German or more likely Italian ground forces, as proven by the ease with which the British seized French ships in British ports or the German seizure of French ships in Bizerte in Tunisia in November 1942.[28][29]

Casualties

| Officers | Petty officers | Sailors, marines | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bretagne | 36 | 151 | 825 | 1012 |

| Dunkerque | 9 | 32 | 169 | 210 |

| Provence | 1 | 2 | — | 3 |

| Strasbourg | — | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Mogador | — | 3 | 35 | 38 |

| Rigault de Genouilly | — | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Terre Neuve | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Armen | — | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Esterel | 1 | 5 | — | 6 |

| Total | 48 | 202 | 1,050 | 1,300 |

| Fleet Air Arm[15] | — | — | — | 2 |

Subsequent events

British–Vichy hostilities

Following the 3 July operation, Darlan ordered the French fleet to attack Royal Navy ships wherever possible; Pétain and his foreign minister Paul Baudouin overruled the order the next day. Military retaliation was conducted through ineffective air raids on Gibraltar but Baudouin noted that "the attack on our fleet is one thing, war is another". As sceptics had warned, there were also complications with the French empire; when French colonial forces defeated de Gaulle's Free French Forces at the Battle of Dakar in September 1940, recruitment for the Free French movement plummeted and Germany responded by permitting Vichy France to maintain its remaining ships armed, rather than demobilised.[31][32]

Gibraltarian civilians

In early June 1940, about 13,500 civilians had been evacuated from Gibraltar to Casablanca in French Morocco. Following the capitulation of the French to the Germans and the attack on Mers-el-Kébir, the Vichy government found their presence an embarrassment. Later in June, 15 British cargo vessels arrived in Casablanca under Commodore Crichton, repatriating 15,000 French servicemen who had been rescued from Dunkirk. Once the French troops had disembarked, the ships were interned until the Commodore agreed to take away the evacuees, who, reflecting tensions generated after the attack on Mers-el-Kébir, were escorted to the ships at bayonet point minus many of their possessions.[33]

Case Anton

On 27 November 1942, the Germans attempted to capture the French fleet based at Toulon—in violation of the armistice terms—as part of Case Anton, the military occupation of Vichy France by Germany. All ships of any military value were scuttled by the French before the arrival of German troops, notably Dunkerque, Strasbourg and seven (four heavy and three light) modern cruisers. For many in the French Navy this was a final proof that there had never been a question of their ships ending up in German hands and that the British action at Mers-el-Kébir had been an unnecessary betrayal.[15] Darlan was true to his promise in 1940 that French ships would not be allowed to fall into German hands. Godfroy, still in command of the French ships neutralised at Alexandria, remained aloof for a while longer but on 17 May 1943 joined the Allies.[34]

Orders of battle

Royal Navy

- HMS Hood – battlecruiser – Flagship

- HMS Resolution – battleship

- HMS Valiant – battleship

- HMS Ark Royal – aircraft carrier

- HMS Arethusa – light cruiser

- HMS Enterprise – light cruiser

- HMS Faulknor – destroyer

- HMS Foxhound – destroyer

- HMS Fearless – destroyer

- HMS Forester – destroyer

- HMS Foresight – destroyer

- HMS Escort – destroyer

- HMS Keppel – destroyer

- HMS Active – destroyer

- HMS Wrestler – destroyer

- HMS Vidette – destroyer

- HMS Vortigern – destroyer

French Navy (Marine Nationale)

- Dunkerque – battleship – Flagship

- Strasbourg – battleship

- Bretagne – battleship

- Provence – battleship

- Commandant Teste – seaplane tender

- Mogador – destroyer

- Volta – destroyer

- Le Terrible – destroyer

- Kersaint – destroyer

- Lynx – destroyer

- Tigre – destroyer

See also

Notes

- ↑ It is impossible for us, your comrades up to now, to allow your fine ships to fall into the power of the German enemy. We are determined to fight on until the end, and if we win, as we think we shall, we shall never forget that France was our Ally, that our interests are the same as hers, and that our common enemy is Germany. Should we conquer we solemnly declare that we shall restore the greatness and territory of France. For this purpose we must make sure that the best ships of the French Navy are not used against us by the common foe. In these circumstances, His Majesty's Government have instructed me to demand that the French Fleet now at Mers el Kebir and Oran shall act in accordance with one of the following alternatives; (a) Sail with us and continue the fight until victory against the Germans. (b) Sail with reduced crews under our control to a British port. The reduced crews would be repatriated at the earliest moment. If either of these courses is adopted by you we will restore your ships to France at the conclusion of the war or pay full compensation if they are damaged meanwhile. (c) Alternatively, if you feel bound to stipulate that your ships should not be used against the Germans lest they break the Armistice, then sail them with us with reduced crews to some French port in the West Indies—Martinique for instance—where they can be demilitarised to our satisfaction, or perhaps be entrusted to the United States and remain safe until the end of the war, the crews being repatriated. If you refuse these fair offers, I must with profound regret, require you to sink your ships within 6 hours. Finally, failing the above, I have orders from His Majesty's Government to use whatever force may be necessary to prevent your ships from falling into German or Italian hands.

Footnotes

- ↑ Playfair 1959, p. 137.

- ↑ Thomas 1997, pp. 643–670.

- ↑ Butler 1971, p. 218.

- ↑ Greene & Massignani 2002, p. 57.

- ↑ Lacouture 1991, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Hansard, War Situation, 25 June 1940, 304–05

- ↑ Greene & Massignani 2002, p. 56.

- 1 2 3 4 Lacouture 1991, p. 247.

- ↑ Bell 1997, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Butler 1971, p. 222.

- ↑ Roskill 1957, pp. 240, 242.

- ↑ Smith 2010, p. 48.

- ↑ Smith 2010, pp. 47–56, 93.

- ↑ Butler 1971, pp. 224–225.

- 1 2 3 Greene & Massignani 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ Brown 2004, p. 198.

- ↑ Greene & Massignani 2002, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Greene & Massignani 2002, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Greene & Massignani 2002, pp. 60–61.

- 1 2 Playfair 1959, p. 142.

- ↑ Greene & Massignani 2002, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Lacouture 1991, p. 246.

- ↑ Smith 2010, pp. 86, 88.

- ↑ Playfair 1959, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Auphan & Mordal 1976, pp. 124–126.

- ↑ Butler 1971, p. 230.

- ↑ Smith 2010, p. 92.

- ↑ Lacouture 1991, p. 249.

- ↑ Smith 2010, p. 404.

- ↑ O'Hara 2009, p. 19.

- ↑ Playfair 1959, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Smith 2010, p. 99.

- ↑ Bond 2003, p. 98.

- ↑ Roskill 1962, pp. 338, 444.

Bibliography

Books

- Auphan, Gabriel; Mordal, Jacques (1976). The French Navy in World War II. London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-8660-3.

- Bell, P. M. H. Bell (1997). France and Britain, 1940–1994: The Long Separation. France and Britain. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-28920-8.

- Bond, Peter (2003). 300 Years of British Gibraltar: 1704–2004. Gibraltar: Peter-Tan Ltd for Government of Gibraltar. OCLC 1005205264.

- Brown, D. (2004). The Road to Oran: Anglo-French Naval Relations, September 1939 – July 1940. Cass: Naval Policy and History. London: Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-7146-5461-4.

- Butler, J. R. M. (1971) [1957]. Grand Strategy: September 1939 – June 1941. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. II (2nd ed.). HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630095-9.

- Greene, J.; Massignani, A. (2002) [1998]. The Naval War in the Mediterranean 1940–1943 (pbk. ed.). Rochester: Chatham. ISBN 978-1-86176-190-3.

- Lacouture, Jean (1991) [1984]. De Gaulle: The Rebel 1890–1944 (English trans. ed.). London: W W Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02699-3.

- O'Hara, Vincent P. (2009). Struggle for the Middle Sea: The Great Navies at War in the Mediterranean Theater, 1940–1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-648-3.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; et al. (1959) [1954]. Butler, J. R. M., ed. The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. I (3rd impr. ed.). HMSO. OCLC 494123451. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Roskill, S. W. (1957) [1954]. Butler, J. R. M., ed. The War at Sea 1939–1945: The Defensive. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. I (4th impr. ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 881709135. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War: The War at Sea 1939–1945. II (3rd impression ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 174453986. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Smith, C. (2010) [2009]. England's Last War Against France: Fighting Vichy 1940–1942 (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2705-5.

Journals

Further reading

- Collier, Paul (2003). The Second World War: The Mediterranean 1940–1945. IV. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-539-6.

- Ehrengardt, Christian-Jacques Ehrengardt; Shores, Christopher J. (1985). L'aviation de Vichy au combat: les campagnes oubliées 3 juillet 1940 – 27 novembre 1942 [The Vichy Air Force in Combat: The Forgotten Campaigns]. Grandes batailles de France. Tome I. Paris: C. Lavauzelle. ISBN 978-2-7025-0092-7.

- Jenkins, E. H. (1979). A History of the French Navy: From its Beginnings to the Present Day. London: Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 978-0-356-04196-4.

- Lasterle, Philippe (2003). "Could Admiral Gensoul Have Averted the Tragedy of Mers el-Kebir?". Journal of Military History. 67 (3): 835–844. ISSN 0899-3718.

- Paxton, Robert O. (1972). Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-47360-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Attack on Mers-el-Kébir. |

- A plan of the Mers-el-Kébir anchorage, hmshood.org.uk

- Mers-El-Kebir (1979) a French made-for-TV movie

- Churchill's Sinking of the French Fleet (3 July 1940), digitalsurvivors.com

- Churchill's Deadly Decision, episode of Secrets of the Dead describing the attack and the events leading up to it

- Kappes, Irwin J. (2003) Mers-el-Kebir: A Battle between Friends, Military History Online