Ancient Corsica

|

| History of Corsica |

The history of Corsica in ancient times was characterised by contests for control of the island among various foreign powers. The successors of the neolithic cultures of the island were able to maintain their distinctive traditions even into Roman times, despite the successive interventions of Etruscans, Carthaginians or Phoenicians, and Greeks. A long period of Roman rule was followed by renewed conflict for control of the island by the Vandals, Byzantines and Saracens.

Geography and etymology

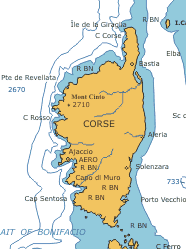

In Roman times the sea surrounding Corsica on the north and west was calledthe Mare Ligusticum, that to the east was the Mare Tyrrhenum and the strait separating the island from Sardinia to the south was the Fretum Gallicum. The location of the island between the Italian mainland to the east, the Gallic mainland to the north, and Sardinia to the south, made Corsica an important strategic point for control of the western Mediterranean sea. Additionally, the island was a significant hub of Mediterranean trade. Corsica was described by Theophrastus[1] as thickly wooded and mountainous. Only the flat, coastal area was suitable for agriculture - especially the space around Aleria on the east coast - the island mainly produced timber and raw materials like copper, iron ore, silver, lead, pitch, wax, and honey. Excepting these products, the island was considered pretty poor, the climate was considered unhealthy and malarial, especially in summer, and generally rough and uncomfortable.[2]

The island was known in Ancient Greek as Kyrnos (Κύρνος) and in Latin as Cyrnus or Corsica. Kyrnos may be derived from a local, Corsican toponym. Scholarship is divided on an origin from a pre-Roman Corsican language word, kors-, meaning 'treetop' according to Eustathius, or rather *krs- (head). The Romans would have added the suffix -ica to this term, while the Greeks added -nos. Another possibility is that the name derives from the Phoenician term Korsai, meaning 'wooded'.[3]

Early settlement

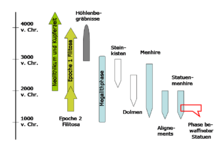

Settlement of Corsica is attested as far back as the 8th millennium BC. The original inhabitants of Corsica were hunter-gatherers from Liguria, who walked to the island over a land bridge created by the modern islands of Elba and Capraia. Around 6000 BC, they were replaced by the Neolithic Cardium pottery culture. As a result of the Würm glaciation the sea level was about 100 metres lower and the island extended closer to the mainland. Until around 5000 BC, it was connected to Sardinia. In the south of the island, a multiphase megalith culture (Filitosa) developed around 3000 BC. Contacts with Sardinia, Etruria, and Liguria are archaeologically attested in the Neolithic period. Terrina, near Aleria is the key site for the Chalcolithic in Corsica. At this time (around 1600 BC), the Torrean civilization developed on the island, leaving behind numerous dolmens, menhirs, and statue menhirs. As in the inner Iberian peninsula, the Balearic islands, Sardinia, and Malta, the megalith culture continued to dominate the island at this time, even as the rest of Europe was already leaving the stone age.[4] In the Bronze age, fixed settlements appear on Corsica, as well as round stone towers, known as torri. The main cultural contacts were with Sardinia and the Italian mainland. Despite these contacts, the development of the island in the Iron age did not lead to urbanisation. The first settlements developed on the island only in the 9th century BC (Capula, Cuccuruzzu, Modria, and Araguina-Sennola at Bonifacio).

According to Diodorus, the inhabitants of island mostly lived as pastoralists. The interior of the island was able to maintain its independence more or less until Roman times.[5]

Greeks, Etruscans and Carthaginians (565-260 BC)

Large-scale urbanisation began only with the settlement of Carthaginians around 565 BC. Herodotus lists the Corsicans among the soldiers of the Carthaginians.[6] Around 545 BC, Greeks from Phocaea[7] founded a city called Alalia (modern Aleria), having fled their home city as a result of the siege of their home city by the Persians under Harpagus. Even before this, Greeks had probably settled on the island in trading communities, perhaps even colonies, which the Etruscans did not appreciate, so near to their own territories. The Phocaeans were not just traders, but pirates and disrupted the trade and exonomic power of the Etruscans and Carthaginians in southern Gaul, Sardinia and Etruria as a result of their raids, even attacking the Italian mainland. As a result, both of the major powers in the western Mediterranean, the Etruscans under the leadership of Caere and Carthaginians, saw the Phocaeans as a threat to their hegemony and went to war against them. In 530 BC, the Phoencians led their allies in a rapid attack.[8] Their victory in the Battle of Alalia meant that the Greeks had to abandon their city and re-settle in the Campanian city of Elea, founded around 540 BC. Sardinia was incorporated firmly into the Carthaginian sphere and Corsica went to the Etruscans. The Greek colonisation of the western Mediterranean ground to a complete halt with the defeat. Diodorus states that the native inhabitants of Corsica had to give the Etruscans tribute of pitch, wax, and honey.[9]

At the beginning of the 6th century BC, Alalia had become an Etruscan settlement. Velthus Spurinna probably sent a military expedition there under the leadership of the Tarquinians. At the beginning of the 4th century, was attacked by Greeks for the last time, commanded by the tyrant Dionysius I of Syracuse.[10] For a short time, troops were stationed at the southern end of the island, possibly at Porto Vecchio.[11]

The Romans were also interested in Corsica even at this early stage. A first attempt to found a Roman colony on the island in 425 BC was a failure.[12] In 296 BC, the island was used by the Romans as a place of exile for Galerius Torquatus.[13]

Roman Republic (259 - 27 BC)

The Roman conquest of Corsica began in 259 BC, when Lucius Cornelius Scipio captured Aleria (Greek 'Alalia') and several Corsican tribes, in the course of the First Punic War. The Roman invasion of the island marked the expansion of the war beyond Sicily to the entire western Mediterranean. In the subsequent peace treaty in 241 BC between the Romans and the defeated Carthaginians, there was no indication that Corsica or Sardinia would pass into the Roman sphere of influence. But, since the Carthaginians were occupied with the Mercenary War, they had no ability to defend them, even when the unrest spread to the nominally Carthaginian island of Sardinia. In the end, the Romans retained both islands. It is not entirely clear whether this control began in 241 BC, but it is certain that the consul for 238/7, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, expanded their dominion over both Corsica and Sardinia, at least in theory.

Both islands were treated as a single military region and were administered by a military government. A rebellion in 231 BC was defeated by Gaius Papirius Maso, for which he received the first triumph in monte Albano.[14] In 227 BC, the two islands became the province of Sardinia et Corsica. Control of the two islands functioned as a kind of buffer zone, protecting the Italian mainland from attacks from the west. Sardinia et Corsica was one of the first two provinces, along with Sicilia, to be founded by the Romans, signifying the final stage in Rome's transformation from a city state to a territorial empire. Unlike with their acquisitions in Italy, the Romans did not bring Corsica, Sardinia and Sicily into their alliance system. Instead, they established a governor, with civil and military responsibilities and the rank of praetor. For the management of the two new provinces, two new praetorships were created, which had not existed previously and the system for the expansion of the empire was established. Originally, this was a military administration for when there was conflict on the island only, but the administration simultaneously gained control of civil government as well and became a permanent fixture. The administration of the province was based in the Sardinian city of Cagliari and the first governor was Marcus Valerius Laevinus. The establishment of the province was contrary to the wishes of the local inhabitants, who had maintained their independence up to this time from both Greeks and Carthaginians.[15] In the following decades, there were multiple rebellions and the conquest of the interior of the island claimed much Roman time and energy. The first colonia, Colonia Mariana, was founded by Gaius Marius around 104 BC and further coloniae followed in the course of the 1st century BC. Marius founded his colonia in the northeast of the island, in the land of the Vanacini tribe.[16] Between December 82 and 1 January 80 BC, Sulla also settled colonists on the island, at Aleria, which he named Colonia Veneria Alaria.

During the Civil War, the island initially belonged to the sphere of Pompey, but was subsequently taken by Julius Caesar. Between 40 and 38 BC, Sextus Pompey, son of Pompey, and his legate Menas occupied the island and terrorised Sardinia, Sicily and even the Italian mainland with a great pirate fleet. Along with the three Triumvirs, Sextus Pompey was one of the four most significant contenders in the warfare after Julius Caesar's death. His fleet largely consisted of thousands of slaves and he also held many strongholds on Corsica. With it, he seriously threatened the Roman grain supply, such that Octavian had to make peace with Sextus Pompey since it was not possible to beat him at the time. In the Pact of Misenum (39 BC), Sextus Pompey was assigned the three islands and Achaia, in return for ending the blockade of the mainland and remaining neutral in the conflict between Octavian and Marc Antony. But Octavian was not satisfied with the area assigned to him and initiated a betrayal which insured that Corsica and Sardinia came into his hands. The conflict erupted anew in 38 BC and Pompey again blockaded the Italian mainland, leading to famine. Later in the same year, Octavian gathered a fleet so powerful that he was able to defeat Sextus Pompey and became ruler of the area again.Corsica remained a private possession of Octavian until the reorganisation of the provinces in 27 BC.

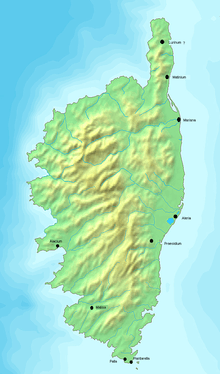

The Romans built only one known street on the island, which is located on the east coast and ran from Piantarella in the south, through the headquarters (Praesidium), to Aleria and Mariana.

Roman Empire (27 BC - AD 300)

In Augustus' provincial reforms, Sardinia et Corsica became a senatorial province. The province was administered by a proconsul with the rank of a praetor. In AD 6, a separate senatorial province of Corsica was established, since Augustus had appropriated the island of Sardinia, where a large garrison was kept under arms, as one of his personal provinces. Even after the return of Sardinia to the Senate in AD 67, the two islands remained separate provinces.

Aleria had been destroyed by Julius Caesar and was refounded by Augustus between 36 and 27 BC as Colonia Veneria Iulia Pacensis Restituta Tertianorum Aleria. After Corsica became a separate province, this city was the seat of the legatus Augusti. Aleria was also an important naval base. At the city's height, it had a population of around 20,000 people. Remnants of the Roman settlement include the remains of an amphitheatre.

Seneca was probably the best-known Roman to spend time on the island as an exile, which he did between AD 41 and 49. At the instigation of Messalina, after conflicting with Caligula and Claudius, he was exiled to the island and remained there for eight years. Only under Nero was he allowed to return to Rome.[17]

In AD 69, the Year of the Four Emperors, the island was held by Otho. The procurator of Corsica was Decumus Pacarius, an opponent of Otho, who attempted to take the island, its fleet, and the local notables over to Vitellius. When he encountered resistance, he attempted to crush it by executing Claudius Pyrrichus, the trierarch of the liburnae and the equis Quintus Certus. As a result, the Corsicans swore an oath of allegiance to Vitellius, very unwillingly. But when Decumus Pacarius began recruiting soldiers, there was a rebellion, which cost him his life. This conflict had no impact on the wider Civil War. Neither Otho, nor Vitellius, nor Vespasian responded to Decumus Pacarius' initial revolt or to his murder.[18]

For the next two hundred years, basically no events are recorded on the island. It was apparently a peaceful and prosperous time. From AD 73, the island was probably administered by imperial officials.[19] Under Trajan (98-117) the province was transferred to Senatorial administration once more. Under Commodus (176-192) or possibly Septimius Severus (193-211), Corsica became an imperial province once more, and was administered by a Procurator Augusti et Praefectus[20]

Plenty of remains from the Roman period can be seen on the island even today. For example, there are remains of bath-houses at Pietrapola, Guagno-les-Bains and Urbalacone.

Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages (AD 300 - 650)

In the reform of the provinces by Diocletian at the beginning of Late Antiquity, Corsica's status was left unchanged. It was administed by a praeses and was assigned to the diocese of Italia Suburbicaria. As elsewhere in the Roman empire, tax pressure increased markedly in this period. As in many other parts of the empire, Corsica was subject to invasions and large-scale migrations, which led to the central government of the Western Roman Empire giving up the island. In 410, the Visigoths conquered the island. In 455[21] the Vandals under king Geiseric, used the island as a base for annual raids on the Italian mainland. Corsica was governed by Vandal officials, rather than Romans and was used by the Vandal kingdom, like the islands of Sardinia and Sicily, as a buffer zone, to protect Vandal North Africa from attacks from the north. In 500, the Ostrogoths conquered the island. In 536, Eastern Roman troops of Emperor Justinian, under the command of Cyril, a subordinate of Belisarius, regained the island,as well as Sardinia and the Balearics, in the course of a many year long operation in the western Mediterranean, whose ultimate goal was the reconquest of North Africa from the Vandals. There is no trace of imperial building work in Corsica, of the sort which took place elsewhere. In 575, the Lombards landed on the island and they established several strategically important coastal sites. The interior of the island, however, remained in Eastern Roman hands

The tax pressure and the various invasions deeply harmed the island. One bond which held Corsica together was the Church, which was deeply embedded on the island. So it is not surprising that a new chapter in the history of the island was opened by the church. Pope Gregory I reclaimed the island during his pontificate (590-604), as a missionary area. In accordance with his command, the populace were further indoctrinated, the church organisation of the island was revised, and canon law was introduced. The long-vacant bishop's seat was permanently re-established and an administrative structure introduced, which even had some impact in the island's interior. Where the decaying Byzantine government intensified social conflict, the church proved a stabilising element and the bishops became the true leaders of the populace.[22]

In the early 7th century, the island faced a new problem with the Saracens, who ravaged the coasts of the island frequently. The Lombards also returned to the island, to fight against the Saracens. The conflict with the Saracens, which also drew in other significant powers that often laid claim to Corsica or a part thereof, dominated the fortunes of the island for several centuries. This period is almost unrecorded, except in the Chronicles of Giovanni della Grossa (1388-1464), which were written much later and are heavily infused with legends.

Historiography

Source material and research on the island are both sparse and as a result there have been few scholarly publications. This results both from the relative insignificance of Corsica in antiquity and from the disinterest of the French academy in the island. Compared with the neighbouring island of Sardinia, which has received significant attention from Italian scholars, research on ancient Corsica is still in its infancy.

In the 19th century, the General-inspector Prosper Mérimée visited Corsica to record the historical monuments on the island. In 1840, he published his findings as Notes d'un voyage en Corse. Intensive research of the early history of Corsica began in the 20th century with Roger Grosjean.[23]

A sign of the neglect of the island is that the 1965 Lexikon der Alten Welt contained no article on Corsica, despite having articles for the other large Mediterranean islands - Crete, Sicily, Cyprus and Sardinia.

References

- ↑ Historia plantarum 5.8

- ↑ Bechert: Die Provinzen des römischen Reiches, pp. 61f.

- ↑ Gerhard Radke, "Corsica," Der Kleine Pauly, Vol. 1 (1964), col. 1324.

- ↑ Richard Pittioni, Propyläen Weltgeschichte, Vol. 1, p. 275.

- ↑ Kulturgeschichte der Antike. Vol. 2: Rom, Berlin 1982.

- ↑ Histories 7.165.

- ↑ They were also attributed with the foundation of Massillia, Emporion, Nikaia, Athenopolis and Antipolis.

- ↑ See Der Neue Pauly. – in earlier literature, it is always described as a battle between Greeks and Carthaginians/Etruscans. 540 BC (Wolfgang Schuller, Griechische Geschichte, p. 14) and 535 BC (Propyläen Weltgeschichte. Vol. 3, S. 678.) are both given as the year of the battle. Different accounts are given of the outcome of battle. Jochen Bleicken (Propyläen Weltgeschichte. vol. 4, p. 45.) speaks of a devastating victory of a Carthaginian-Etruscan coalition, but others report that the Greeks barely scraped a victory but their city was so badly damaged that they had to abandon it (Hermann Bengtson, Römische Geschichte. München 1973, p. 17.). Alfred Heuss (Propyläen Weltgeschichte. Vol 3, p. 201) speaks of 'an unclear result.'

- ↑ Diodoros 5.13.4 & 11.88.5.

- ↑ Alfred Heuss, Propyläen Weltgeschichte. Vol. 3, p. 387.

- ↑ Bengtson: Römische Geschichte, p. 39.

- ↑ Theophrastus: Historia Plantarum. 5.8.2 and an inscription of a 'Claudius' (Klautie) on an Attic kylix of around 425 BC found in a grave at Casabiada.

- ↑ Theophilos I. FGrH.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus 3.6.5 – since the Senate refused him his triumph, he celebrated one more or less independently on Mons Albanus.

- ↑ Bechert: Die Provinzen des römischen Reiches, p. 61.

- ↑ CIL X, 8038

- ↑ Bengtson: Römische Geschichte, p. 253.

- ↑ Tacitus, Histories 2,16.

- ↑ CIL X, 8023 and 8024.

- ↑ CIL III, 6813 and CIL X, 7580.

- ↑ TheLexikon des Mittelalters says 455, Moses Finley in Ancient Sicily says 445, and Jochen Martin in Spatantike und Völkerwanderung: "after 455."

- ↑ On the role of the church, see Lexikon des Mittelalters.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kathe: Korsika, Reise Know-How Verlag Peter Rump, ISBN 3-8317-1448-7

Bibliography

- B. Andrei: Korsika. In: Lexikon des Mittelalters, Bd. 5 (1999), Sp. 1452–1454.

- Tilmann Bechert: Die Provinzen des Römischen Reiches. Einführung und Überblick. Von Zabern, Mainz 1999 (Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie/Sonderband zur Antiken Welt/Orbis provinciarum) ISBN 3-8053-2399-9.

- Hermann Bengtson: Römische Geschichte. Republik und Kaiserzeit bis 284 n. Chr. C.H. Beck, 7. Auflage, München 1995, ISBN 3-406-02505-6.

- Cinzia Vismara, Philippe Pergola, Daniel Istria, Rossana Martorelli: Sardinien und Korsika in römischer Zeit. Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-8053-3564-5 (Zaberns Bildbände zur Archäologie)

- Raimondo Zucca: Corsica. In: Der Neue Pauly, Bd. 3 (1997), Sp. 208–210.

External links

- Korsische Chronologie auf Corse Web