Abrupt climate change

An abrupt climate change occurs when the climate system is forced to transition to a new climate state at a rate that is determined by the climate system energy-balance, and which is more rapid than the rate of change of the external forcing.[1] Past events include the end of the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse,[2] Younger Dryas,[3] Dansgaard-Oeschger events, Heinrich events and possibly also the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum.[4] The term is also used within the context of global warming to describe sudden climate change that is detectable over the time-scale of a human lifetime. One proposed cause of such events is feedback loops within the climate system both enhance small perturbations and cause a variety of stable states.[5]

Timescales of events described as 'abrupt' may vary dramatically. Changes recorded in the climate of Greenland at the end of the Younger Dryas, as measured by ice-cores, imply a sudden warming of +10 °C (+18 °F) within a timescale of a few years.[6] Other abrupt changes are the +4 °C (+7.2 °F) on Greenland 11,270 years ago[7] or the abrupt +6 °C (11 °F) warming 22,000 years ago on Antarctica.[8] By contrast, the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum may have initiated anywhere between a few decades and several thousand years. Finally, Earth Systems models project that under ongoing greenhouse gas emissions as early as 2047, the Earth's near surface temperature could depart from the range of variability in the last 150 years, affecting over 3 billion people and most places of great species diversity on Earth.[9]

Definitions

According to the Committee on Abrupt Climate Change of the National Research Council:[1][10]

There are essentially two definitions of abrupt climate change:

- In terms of physics, it is a transition of the climate system into a different mode on a time scale that is faster than the responsible forcing.

- In terms of impacts, "an abrupt change is one that takes place so rapidly and unexpectedly that human or natural systems have difficulty adapting to it".

These definitions are complementary: the former gives some insight into how abrupt climate change comes about ; the latter explains why there is so much research devoted to it.

General

Possible tipping elements in the climate system include: regional effects of global warming, some of which had abrupt onset and may therefore be regarded as abrupt climate change.[11] Scientists have stated that "Our synthesis of present knowledge suggests that a variety of tipping elements could reach their critical point within this century under anthropogenic climate change."[11]

It has been postulated that teleconnections, oceanic and atmospheric processes, on different timescales, connect both hemispheres during abrupt climate change.[12]

The IPCC states that global warming "could lead to some effects that are abrupt or irreversible".[13]

In an article in Science, Richard Alley et al. said "it is conceivable that human forcing of climate change is increasing the probability of large, abrupt events. Were such an event to recur, the economic and ecological impacts could be large and potentially serious."[14]

A 2013 report from the U.S. National Research Council called for attention to the abrupt impacts of climate change, stating that even steady, gradual change in the physical climate system can have abrupt impacts elsewhere—in human infrastructure and ecosystems for example—if critical thresholds are crossed. The report emphasizes the need for an early warning system that could help society better anticipate sudden changes and emerging impacts.[15]

Scientific understanding of abrupt climate change is generally poor.[16] The probability of abrupt change for some climate related feedbacks may be low.[17][18] Factors that may increase the probability of abrupt climate change include higher magnitudes of global warming, warming that occurs more rapidly, and warming that is sustained over longer time periods.[18]

Climate models

Climate models are unable yet to predict abrupt climate change events, or most of the past abrupt climate shifts.[19] A potential abrupt feedback due to thermokarst lake formations in the Arctic, in response to thawing permafrost soils, releasing additional greenhouse gas methane, is currently not accounted for in climate models.[20]

Possible precursor

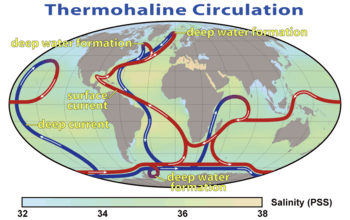

Most abrupt climate shifts, are likely due to sudden circulation shifts, analogous to a flood cutting a new river channel. The best-known examples are the several dozen shutdowns of the North Atlantic Ocean's Meridional Overturning Circulation during the last ice age, affecting climate worldwide.[14]

- The current warming of the Arctic, the duration of the summer season, is considered abrupt and massive.[19]

- Antarctic ozone depletion caused significant atmospheric circulation changes.[19]

- There have also been two occasions when the Atlantic's Meridional Overturning Circulation lost a crucial safety factor. The Greenland Sea flushing at 75 °N shut down in 1978, recovering over the next decade.[21] Then the second-largest flushing site, the Labrador Sea, shut down in 1997[22] for ten years.[23] While shutdowns overlapping in time have not been seen during the fifty years of observation, previous total shutdowns had severe worldwide climate consequences.[14]

Effects

Global oceans have established patterns of currents. Several potential disruptions to this system of currents have been identified as a result of global warming:

- Increasing frequency of El Niño events[24][25]

- Potential disruption to the thermohaline circulation, such as that which may have occurred during the Younger Dryas event.[26][27]

- Changes to the North Atlantic oscillation[28]

Weather

Hansen et al. 2015 found, that the shutdown or substantial slowdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), besides possibly contributing to extreme end-Eemian events, will cause a more general increase of severe weather. Additional surface cooling from ice melt increases surface and lower tropospheric temperature gradients, and causes in model simulations a large increase of mid-latitude eddy energy throughout the midlatitude troposphere. This in turn leads to an increase of baroclinicity produced by stronger temperature gradients, which provides energy for more severe weather events.[29]

Consequential effects

Abrupt climate change has likely been the cause of wide ranging and severe effects:

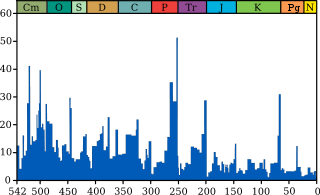

- Mass extinctions in the past, most notably the Permian-Triassic Extinction event (often referred to as the great dying) and the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse, have been suggested as a consequence of abrupt climate change.[2][30][31]

- Loss of biodiversity. Without interference from abrupt climate change and other extinction events the biodiversity of this planet would continue to grow.[32]

- Rapid ocean acidification,[33] which can harm marine life (such as corals).[34]

Climate feedback effects

.jpg)

One source of abrupt climate change effects is a feedback process, in which a warming event causes a change which leads to further warming. This can also apply to cooling. Example of such feedback processes are:

- Ice-albedo feedback, where the advance or retreat of ice cover alters the 'whiteness' of the earth, and its ability to absorb the sun's energy.[36]

- Soil carbon feedback concerns releases of carbon from soils, in response to global warming.

- The dying and burning of forests, as a result of global warming[37]

Volcanism

Isostatic rebound in response to glacier retreat (unloading), increased local salinity, have been attributed to increased volcanic activity at the onset of the abrupt Bølling-Allerød warming, are associated with the interval of intense volcanic activity, hinting at a interaction between climate and volcanism - enhanced short-term melting of glaciers, possibly via albedo changes from particle fallout on glacier surfaces.[38]

Past events

Several periods of abrupt climate change have been identified in the paleoclimatic record. Notable examples include:

- About 25 climate shifts, called Dansgaard-Oeschger cycles, which have been identified in the ice core record during the glacial period over the past 100,000 years.

- The Younger Dryas event, notably its sudden end. It is the most recent of the Dansgaard-Oeschger cycles and began 12,900 years ago and moved back into a warm-and-wet climate regime about 11,600 years ago. It has been suggested that: "The extreme rapidity of these changes in a variable that directly represents regional climate implies that the events at the end of the last glaciation may have been responses to some kind of threshold or trigger in the North Atlantic climate system."[39] A model for this event based on disruption to the thermohaline circulation has been supported by other studies.[27]

- The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, timed at 55 million years ago, which may have been caused by the clathrate gun effect,[40] although potential alternative mechanisms have been identified.[41] This was associated with rapid ocean acidification[33]

- The Permian-Triassic Extinction Event, also known as the great dying, in which up to 95% of all species became extinct, has been hypothesized to be related to a rapid change in global climate.[42][43] Life on land took 30 million years to recover.[30]

- The Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse occurred 300 million years ago, at which time tropical rainforests were devastated by climate change. The cooler, drier climate had a severe effect on the biodiversity of amphibians, the primary form of vertebrate life on land.[2]

There are also abrupt climate changes associated with the catastrophic draining of glacial lakes. One example of this is the 8.2 kiloyear event, which associated with the draining of Glacial Lake Agassiz.[44] Another example is the Antarctic Cold Reversal, c. 14,500 years before present (BP), which is believed to have been caused by a meltwater pulse from the Antarctic ice sheet. These rapid meltwater release events have been hypothesized as a cause for Dansgaard-Oeschger cycles,[45]

A 2017 study concluded that similar conditions to today's Antarctic ozone hole (atmospheric circulation and hydroclimate changes), ∼17,700 years ago, when stratospheric ozone depletion contributed to abrupt accelerated Southern Hemisphere deglaciation. The event coincidentally happened with an estimated 192-year series of massive volcanic eruptions, attributed to Mount Takahe in West Antarctica.[46]

See also

References

- 1 2 Committee on Abrupt Climate Change, National Research Council. (2002). "Definition of Abrupt Climate Change". Abrupt climate change : inevitable surprises. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-309-07434-6.

- 1 2 3 Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J.; Falcon-Lang, H.J. (2010). "Rainforest collapse triggered Pennsylvanian tetrapod diversification in Euramerica" (PDF). Geology. 38 (12): 1079–1082. Bibcode:2010Geo....38.1079S. doi:10.1130/G31182.1.

- ↑ Broecker, W. S. (May 2006). "Geology. Was the Younger Dryas triggered by a flood?". Science. 312 (5777): 1146–1148. doi:10.1126/science.1123253. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16728622.

- ↑ Committee on Abrupt Climate Change, Ocean Studies Board, Polar Research Board, Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, Division on Earth and Life Studies, National Research Council. (2002). Abrupt climate change : inevitable surprises. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-309-07434-7.

- ↑ Rial, J. A.; Pielke Sr., R. A.; Beniston, M.; Claussen, M.; Canadell, J.; Cox, P.; Held, H.; De Noblet-Ducoudré, N.; Prinn, R.; Reynolds, J. F.; Salas, J. D. (2004). "Nonlinearities, Feedbacks and Critical Thresholds within the Earth's Climate System" (PDF). Climatic Change. 65: 11–00. doi:10.1023/B:CLIM.0000037493.89489.3f. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Grachev, A.M.; Severinghaus, J.P. (2005). "A revised +10±4 °C magnitude of the abrupt change in Greenland temperature at the Younger Dryas termination using published GISP2 gas isotope data and air thermal diffusion constants". Quaternary Science Reviews. 24 (5–6): 513–9. Bibcode:2005QSRv...24..513G. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.10.016.

- ↑ Kobashi, T.; Severinghaus, J.P.; Barnola, J. (30 April 2008). "4 ± 1.5 °C abrupt warming 11,270 yr ago identified from trapped air in Greenland ice". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 268 (3–4): 397–407. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.268..397K. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.01.032.

- ↑ Taylor, K.C.; White, J; Severinghaus, J; Brook, E; Mayewski, P; Alley, R; Steig, E; Spencer, M; Meyerson, E; Meese, D; Lamorey, G; Grachev, A; Gow, A; Barnett, B (January 2004). "Abrupt climate change around 22 ka on the Siple Coast of Antarctica". Quaternary Science Reviews. 23 (1–2): 7–15. Bibcode:2004QSRv...23....7T. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.09.004.

- ↑ Mora, C (2013). "The projected timing of climate departure from recent variability". Nature. 502: 183–187. Bibcode:2013Natur.502..183M. doi:10.1038/nature12540. PMID 24108050.

- ↑ Harunur Rashid; Leonid Polyak; Ellen Mosley-Thompson (2011). "Abrupt climate change: mechanisms, patterns, and impacts". American Geophysical Union. ISBN 9780875904849. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- 1 2 Lenton, T. M.; Held, H.; Kriegler, E.; Hall, J. W.; Lucht, W.; Rahmstorf, S.; Schellnhuber, H. J. (2008). "Inaugural Article: Tipping elements in the Earth's climate system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (6): 1786. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.1786L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705414105. PMC 2538841.

- ↑ Markle; et al. (2016). "Global atmospheric teleconnections during Dansgaard–Oeschger events". Nature.

- ↑ "Summary for Policymakers". Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report (PDF). IPCC. 17 November 2007.

- 1 2 3 Alley, R. B.; Marotzke, J.; Nordhaus, W. D.; Overpeck, J. T.; Peteet, D. M.; Pielke Jr, R. A.; Pierrehumbert, R. T.; Rhines, P. B.; Stocker, T. F.; Talley, L. D.; Wallace, J. M. (Mar 2003). "Abrupt Climate Change" (PDF). Science. 299 (5615): 2005–2010. Bibcode:2003Sci...299.2005A. doi:10.1126/science.1081056. PMID 12663908.

- ↑ http://dels.nas.edu/Report/Report/18373

- ↑ US National Research Council (2010). "Advancing the Science of Climate Change: Report in Brief". Washington, DC: National Academies Press. , p.3. PDF of Report

- ↑ Clark, P.U.; et al. (December 2008). "Executive Summary". Abrupt Climate Change. A Report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research. Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey. , pp. 1–7. Report website Archived 4 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 IPCC. "Summary for Policymakers". Sec. 2.6. The Potential for Large-Scale and Possibly Irreversible Impacts Poses Risks that have yet to be Reliably Quantified. , in IPCC TAR WG2 2001

- 1 2 3 Mayewski, Paul Andrew (2016). "Abrupt climate change: Past, present and the search for precursors as an aid to predicting events in the future (Hans Oeschger Medal Lecture)". Bibcode:2016EGUGA..18.2567M. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ "Unexpected Future Boost of Methane Possible from Arctic Permafrost". NASA. 2018.

- ↑ Schlosser P, Bönisch G, Rhein M, Bayer R (1991). "Reduction of deepwater formation in the Greenland Sea during the 1980s: Evidence from tracer data" (PDF). Science. 251 (4997): 1054–1056. Bibcode:1991Sci...251.1054S. doi:10.1126/science.251.4997.1054. PMID 17802088.

- ↑ Rhines, P. B. (2006). "Sub-Arctic oceans and global climate". Weather. 61 (4): 109–118. Bibcode:2006Wthr...61..109R. doi:10.1256/wea.223.05.

- ↑ Våge, K.; Pickart, R. S.; Thierry, V.; Reverdin, G.; Lee, C. M.; Petrie, B.; Agnew, T. A.; Wong, A.; Ribergaard, M. H. (2008). "Surprising return of deep convection to the subpolar North Atlantic Ocean in winter 2007–2008". Nature Geoscience. 2 (1): 67. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2...67V. doi:10.1038/ngeo382.

- ↑ Trenberth, K. E.; Hoar, T. J. (1997). "El Niño and climate change" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 24 (23): 3057–3060. Bibcode:1997GeoRL..24.3057T. doi:10.1029/97GL03092. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- ↑ Meehl, G. A.; Washington, W. M. (1996). "El Niño-like climate change in a model with increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations". Nature. 382 (6586): 56–60. Bibcode:1996Natur.382...56M. doi:10.1038/382056a0.

- ↑ Broecker, W. S. (1997). "Thermohaline Circulation, the Achilles Heel of Our Climate System: Will Man-Made CO2 Upset the Current Balance?" (PDF). Science. 278 (5343): 1582–1588. Bibcode:1997Sci...278.1582B. doi:10.1126/science.278.5343.1582. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2009.

- 1 2 Manabe, S.; Stouffer, R. J. (1995). "Simulation of abrupt climate change induced by freshwater input to the North Atlantic Ocean" (PDF). Nature. 378 (6553): 165. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..165M. doi:10.1038/378165a0.

- ↑ Beniston, M.; Jungo, P. (2002). "Shifts in the distributions of pressure, temperature and moisture and changes in the typical weather patterns in the Alpine region in response to the behavior of the North Atlantic Oscillation" (PDF). Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 71 (1–2): 29–42. Bibcode:2002ThApC..71...29B. doi:10.1007/s704-002-8206-7.

- ↑ J. Hansen, M. Sato, P. Hearty, R. Ruedy, M. Kelley, V. Masson-Delmotte, G. Russell, G. Tselioudis, J. Cao, E. Rignot, I. Velicogna, E. Kandiano, K. von Schuckmann, P. Kharecha, A. N. Legrande, M. Bauer, and K.-W. Lo (2015). "Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming is highly dangerous". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions. 15: 20059–20179. Bibcode:2015ACPD...1520059H. doi:10.5194/acpd-15-20059-2015.

Our results at least imply that strong cooling in the North Atlantic from AMOC shutdown does create higher wind speed. * * * The increment in seasonal mean wind speed of the northeasterlies relative to preindustrial conditions is as much as 10–20 %. Such a percentage increase of wind speed in a storm translates into an increase of storm power dissipation by a factor ∼1.4–2, because wind power dissipation is proportional to the cube of wind speed. However, our simulated changes refer to seasonal mean winds averaged over large grid-boxes, not individual storms.* * * Many of the most memorable and devastating storms in eastern North America and western Europe, popularly known as superstorms, have been winter cyclonic storms, though sometimes occurring in late fall or early spring, that generate near-hurricane-force winds and often large amounts of snowfall. Continued warming of low latitude oceans in coming decades will provide more water vapor to strengthen such storms. If this tropical warming is combined with a cooler North Atlantic Ocean from AMOC slowdown and an increase in midlatitude eddy energy, we can anticipate more severe baroclinic storms.

- 1 2 Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

- ↑ Crowley, T. J.; North, G. R. (May 1988). "Abrupt Climate Change and Extinction Events in Earth History". Science. 240 (4855): 996–1002. Bibcode:1988Sci...240..996C. doi:10.1126/science.240.4855.996. PMID 17731712.

- ↑ Sahney, S.; Benton, M.J.; Ferry, P.A. (2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land" (PDF). Biology Letters. 6 (4): 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. PMC 2936204. PMID 20106856.

- 1 2 Zachos, J. C.; Röhl, U.; Schellenberg, S. A.; Sluijs, A.; Hodell, D. A.; Kelly, D. C.; Thomas, E.; Nicolo, M.; Raffi, I.; Lourens, L. J.; McCarren, H.; Kroon, D. (Jun 2005). "Rapid acidification of the ocean during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum". Science. 308 (5728): 1611–1615. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1611Z. doi:10.1126/science.1109004. PMID 15947184.

- ↑ Fabry, V. J.; Seibel, B. A.; Feely, R. A.; Orr, J. C. (2008). "Impacts of ocean acidification on marine fauna and ecosystem processes" (PDF). ICES Journal of Marine Science. 65 (3): 414–432. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsn048.

- ↑ "Thermodynamics: Albedo". NSIDC.

- ↑ Comiso, J. C. (2002). "A rapidly declining perennial sea ice cover in the Arctic" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 29 (20): 17–1–17–4. Bibcode:2002GeoRL..29.1956C. doi:10.1029/2002GL015650. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Malhi, Y.; Aragao, L. E. O. C.; Galbraith, D.; Huntingford, C.; Fisher, R.; Zelazowski, P.; Sitch, S.; McSweeney, C.; Meir, P. (Feb 2009). "Special Feature: Exploring the likelihood and mechanism of a climate-change-induced dieback of the Amazon rainforest" (PDF). PNAS. 106 (49): 20610–20615. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620610M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804619106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2791614. PMID 19218454.

- ↑ Praetorius; et al. (2016). Interaction between climate, volcanism, and isostatic rebound in Southeast Alaska during the last deglaciation. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Bibcode:2016E&PSL.452...79P. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.07.033.

- ↑ Alley, R. B.; Meese, D. A.; Shuman, C. A.; Gow, A. J.; Taylor, K. C.; Grootes, P. M.; White, J. W. C.; Ram, M.; Waddington, E. D.; Mayewski, P. A.; Zielinski, G. A. (1993). "Abrupt increase in Greenland snow accumulation at the end of the Younger Dryas event" (PDF). Nature. 362 (6420): 527–529. Bibcode:1993Natur.362..527A. doi:10.1038/362527a0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2010.

- ↑ Farley, K. A.; Eltgroth, S. F. (2003). "An alternative age model for the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum using extraterrestrial 3He". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 208 (3–4): 135–148. Bibcode:2003E&PSL.208..135F. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00017-7.

- ↑ Pagani, M.; Caldeira, K.; Archer, D.; Zachos, C. (Dec 2006). "Atmosphere. An ancient carbon mystery". Science. 314 (5805): 1556–1557. doi:10.1126/science.1136110. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17158314.

- ↑ Benton, M. J.; Twitchet, R. J. (2003). "How to kill (almost) all life: the end-Permian extinction event" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 18 (7): 358–365. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00093-4.

- ↑ Crowley, Tj; North, Gr (May 1988). "Abrupt Climate Change and Extinction Events in Earth History". Science. 240 (4855): 996–1002. Bibcode:1988Sci...240..996C. doi:10.1126/science.240.4855.996. PMID 17731712.

- ↑ Alley, R. B.; Mayewski, P. A.; Sowers, T.; Stuiver, M.; Taylor, K. C.; Clark, P. U. (1997). "Holocene climatic instability: A prominent, widespread event 8200 yr ago". Geology. 25 (6): 483. Bibcode:1997Geo....25..483A. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0483:HCIAPW>2.3.CO;2.

- ↑ Bond, G.C.; Showers, W.; Elliot, M.; Evans, M.; Lotti, R.; Hajdas, I.; Bonani, G.; Johnson, S. (1999). "The North Atlantic's 1–2 kyr climate rhythm: relation to Heinrich events, Dansgaard/Oeschger cycles and the little ice age" (PDF). In Clark, P.U.; Webb, R.S.; Keigwin, L.D. Mechanisms of Global Change at Millennial Time Scales. Geophysical Monograph. American Geophysical Union, Washington DC. pp. 59–76. ISBN 0-87590-033-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008.

- ↑ McConnell et al. (2017). "Synchronous volcanic eruptions and abrupt climate change ∼17.7 ka plausibly linked by stratospheric ozone depletion". PNAS. doi:10.1073/pnas.1705595114.

Further reading

- Alley, Richard B. (2000). The Two-Mile Time Machine: Ice Cores, Abrupt Climate Change, and Our Future. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00493-5.

- Calvin, William H. (2002). A Brain for All Seasons: Human Evolution and Abrupt Climate Change. London and Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-09201-1.

- Calvin, William H. (2008). Global fever: How to treat climate change. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Cox, John (2005). Climate Crash: Abrupt Climate Change and What It Means for Our Future. Washington, D.C: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0-309-09312-0.

- Clark, P.U., A.J. Weaver (coordinating lead authors), E. Brook, E.R. Cook, T.L. Delworth, and K. Steffen (chapter lead authors). (2008). "Abrupt Climate Change. A report by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research". Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 12 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-11.

- Drummond, Carl N.; Wilkinson, Bruce H. (2006). "Interannual Variability in Climate Data". Journal of Geology. 114 (3): 325–39. Bibcode:2006JG....114..325D. doi:10.1086/500992.

- Parson, Edward; Dessler, Andrew Emory (2006). The Science and Politics of Global Climate Change: A Guide to the Debate. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53941-2.

- National Research Council of the National Academies (2013). "ABRUPT IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE; ANTICIPATING SURPRISES".

- Schwartz, Peter; Randall, Doug (October 2003). "An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for United States National Security" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2009.