Reforestation

Reforestation is the natural or intentional restocking of existing forests and woodlands (forestation) that have been depleted, usually through deforestation.[1] Reforestation can be used to rectify or improve the quality of human life by soaking up pollution and dust from the air, rebuild natural habitats and ecosystems, mitigate global warming since forests facilitate biosequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide,[2] and harvest for resources, particularly timber, but also non-timber forest products.

A similar concept, afforestation, another type of forestation, refers to the process of restoring and recreating areas of woodlands or forests that may have existed long ago but were deforested or otherwise removed at some point in the past or lacked it naturally (e.g., natural grasslands). Sometimes the term "re-afforestation" is used to distinguish between the original forest cover and the later re-growth of forest to an area. Special tools, e.g. tree planting bars, are used to make planting of trees easier and faster.

Management

A debated issue in managed reforestation is whether or not the succeeding forest will have the same biodiversity as the original forest. If the forest is replaced with only one species of tree and all other vegetation is prevented from growing back, a monoculture forest similar to agricultural crops would be the result. However, most reforestation involves the planting of different lots of seed of seedlings taken from the area, often of multiple species.[3] Another important factor is the natural regeneration of a wide variety of plant and animal species that can occur on a clear cut. In some areas the suppression of forest fires for hundreds of years has resulted in large single aged and single species forest stands. The logging of small clear cuts and/or prescribed burning actually increases the biodiversity in these areas by creating a greater variety of tree stand ages and species.

For harvesting

Reforestation need not be only used for recovery of accidentally destroyed forests. In some countries, such as Finland, many of the forests are managed by the wood products and pulp and paper industry. In such an arrangement, like other crops, trees are planted to replace those that have been cut. In such circumstances, the industry can cut the trees in a way to allow easier reforestation. The wood products industry systematically replaces many of the trees it cuts, employing large numbers of summer workers for tree planting work. For example, in 2010, Weyerhaeuser reported planting 50 million seedlings.[4] However replanting an old-growth forest with a plantation is not replacing the old with the same characteristics in the new.

In just 20 years, a teak plantation in Costa Rica can produce up to about 400 m³ of wood per hectare. As the natural teak forests of Asia become more scarce or difficult to obtain, the prices commanded by plantation-grown teak grows higher every year. Other species such as mahogany grow more slowly than teak in Tropical America but are also extremely valuable. Faster growers include pine, eucalyptus, and Gmelina.[5]

Reforestation, if several indigenous species are used, can provide other benefits in addition to financial returns, including restoration of the soil, rejuvenation of local flora and fauna, and the capturing and sequestering of 38 tons of carbon dioxide per hectare per year.[6]

The reestablishment of forests is not just simple tree planting. Forests are made up of a community of species and they build dead organic matter into soils over time. A major tree-planting program could enhance the local climate and reduce the demands of burning large amounts of fossil fuels for cooling in the summer.[7]

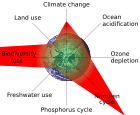

For climate change mitigation

Forests are an important part of the global carbon cycle because trees and plants absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. By removing this greenhouse gas from the air, forests function as terrestrial carbon sinks, meaning they store large amounts of carbon. At any time, forests account for as much as double the amount of carbon in the atmosphere.[8]:1456 Even as more anthropogenic carbon is produced, forests remove around three billion tons of anthropogenic carbon every year. This amounts to about 30% of all carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels. Therefore, an increase in the overall forest cover around the world would tend to mitigate global warming.

There are four major strategies available to mitigate carbon emissions through forestry activities: increase the amount of forested land through a reforestation process; increase the carbon density of existing forests at a stand and landscape scale; expand the use of forest products that will sustainably replace fossil-fuel emissions; and reduce carbon emissions that are caused from deforestation and degradation.[8]:1456

Achieving the first strategy would require enormous and wide-ranging efforts. However, there are many organizations around the world that encourage tree-planting as a way to offset carbon emissions for the express purpose of fighting climate change. For example, in China, the Jane Goodall Institute, through their Shanghai Roots & Shoots division, launched the Million Tree Project in Kulun Qi, Inner Mongolia to plant one million trees to stop desertification and help curb climate change.[9][10] China has used 24 billion metres squared of new forest plantation and natural forest regrowth to offset 21% of Chinese fossil fuel emissions in 2000.[8]:1456 In Java, Indonesia each newlywed couple is to give whoever is sermonizing their wedding 5 seedlings to combat global warming. Each couple that wishes to have a divorce has to give 25 seedlings to whoever divorces them.[11]

The second strategy has to do with selecting species for tree-planting. In theory, planting any kind of tree to produce more forest cover would absorb more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. On the other hand, a genetically modified tree specimen might grow much faster than any other regular tree.[12]:93 Some of these trees are already being developed in the lumber and biofuel industries. These fast-growing trees would not only be planted for those industries but they can also be planted to help absorb carbon dioxide faster than slow-growing trees.[12]:93

Extensive forest resources placed anywhere in the world will not always have the same impact. For example, large reforestation programs in boreal or subarctic regions have a limited impact on climate mitigation. This is because it substitutes a bright snow-dominated region that reflects the sunlight with dark forest canopies. On the other hand, a positive example would be reforestation projects in tropical regions, which would lead to a positive biophysical change such as the formation of clouds. These clouds would then reflect the sunlight, creating a positive impact on climate mitigation.[8]:1457

There is an advantage to planting trees in tropical climates with wet seasons. In such a setting, trees have a quicker growth rate because they can grow year-round. Trees in tropical climates have, on average, larger, brighter, and more abundant leaves than non-tropical climates. A study of the girth of 70,000 trees across Africa has shown that tropical forests are soaking up more carbon dioxide pollution than previously realized. The research suggests almost one fifth of fossil fuel emissions are absorbed by forests across Africa, Amazonia and Asia. Simon Lewis, a climate expert at the University of Leeds, who led the study, said: "Tropical forest trees are absorbing about 18% of the carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere each year from burning fossil fuels, substantially buffering the rate of change."[13]

It is also important to deal with the rate of deforestation. At this point, there are 13 billion metres squared of tropical regions that are deforested every year. There is potential for these regions to reduce rates of deforestation by 50% by 2050, which would be a huge contribution to stabilize the global climate.[8]:1456

Incentives

Some incentives for reforestation can be as simple as a financial compensation. Streck and Scholz (2006) explain how a group of scientists from various institutions have developed a compensated reduction of deforestation approach which would reward developing countries that disrupt any further act of deforestation. Countries that participate and take the option to reduce their emissions from deforestation during a committed period of time would receive financial compensation for the carbon dioxide emissions that they avoided.[14]:875 To raise the payments, the host country would issue government bonds or negotiate some kind of loan with a financial institution that would want to take part in the compensation promised to the other country. The funds received by the country could be invested to help find alternatives to the extensive cutdown of forests. This whole process of cutting emissions would be voluntary, but once the country has agreed to lower their emissions they would be obligated to reduce their emissions. However, if a country was not able to meet their obligation, their target would get added to their next commitment period. The authors of these proposals see this as a solely government-to-government agreement; private entities would not participate in the compensation trades.[14]:876

Examples

Sub-Saharan Africa

One plan in this region involves planting a nine-mile width of trees on the Southern Border of the Sahara Desert.[15] The Great Green Wall initiative is a pan-African proposal to “green” the continent from west to east in order to battle desertification. It aims at tackling poverty (through employment of workers required for the project) and the degradation of soils in the Sahel-Saharan region, focusing on a strip of land of 15 km (9 mi) wide and 7,500 km (4,750 mi) long from Dakar to Djibouti.[16]

Canada

Natural Resources Canada (The Department of Natural Resources) states that the national forest cover was decreased by 0.34% from 1990 to 2015, and Canada has the lowest deforestation rate in the world.[17] The forest industry is one of the main industries in Canada which contributes about 7% of Canadian economy[18], and about 9% of the forests on earth are in Canada.[19] Therefore, Canada has many policies and laws to commit to sustainable forest management. For example, 94% of Canadian forests are public land, and the government obligates planting trees after harvesting to public forests.[20]

China

In China, extensive replanting programs have existed since the 1970s. Programs have had overall success. The forest cover has increased from 12% of China's land area to 16%. However, specific programs have had limited success. The "Green Wall of China", an attempt to limit the expansion of the Gobi Desert is planned to be 2,800 miles (4,500 km) long and to be completed in 2050. China plans to plant 26 billion trees in the next decade that is two trees for every Chinese citizen per year.[21] China requires that students older than 11 years old plant one tree a year until their high school graduation.[22]

In the years 2013-2018, China planted 338,000 square kilometres of forests, what cost 82.88 billions dollars[23]. In 2018 21.7% of China's territory is covered by forests. Until 2035 China wants to expand it to 26%. The total area of China is 9,596,961 km2(see China), so it means plant 412,669 square kilometres more[24].

Germany

Reforestation is required as part of the federal forest law. 31% of Germany is forested, according to the second forest inventory of 2001–2003. The size of the forest area in Germany increased between the first and the second forest inventory due to forestation of degenerated bogs and agricultural areas.[25]

India

Jadav Payeng had received national awards for reforestation efforts, known as the "Molai forest". He planted 1400 hectors of forest on the bank of river Brahmaputra alone. There are active reforestation efforts throughout the country. In 2016, India more than 50 million trees were planted in Uttar Pradesh and in 2017, more than 66 million trees were planted in Madhya Pradesh. [26] In addition to this and individual efforts, there are startup companies, such as Afforest, that are being created over the country working on reforestation.[27]

Israel

Since 1948, large reforestation and afforestation projects were accomplished in Israel. 240 millions trees were planted. The carbon sequestration rate in these forests is similar to the europeen temperate forests[28][29]

Japan

The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery explain that about two-thirds of Japanese land is covered with forests[30], and it was almost unchanged from 1966 to 2012.[31] Japan needs to reduce 26% of green house gas emission from 2013 by 2030 to accomplish Paris Agreement and is trying to reduce 2% of them by forestry.[32]

Mass environmental and human-body pollution along with relating deforestation, water pollution, smoke damage, and loss of soils caused by mining operations in Ashio, Tochigi became the first environmental social issue in Japan, efforts by Shōzō Tanaka had grown to large campaigns against copper operation. This led to the creation of 'Watarase Yusuichi Pond', to settle the pollution which is a Ramsar site today. Reforestation was conducted as a part of afforestation due to inabilities of self-recovering by the natural land itself due to serious soil pollution and loss of woods consequence in loss of soils for plants to grow, thus needing artificial efforts involving introducing of healthy soils from outside. Starting since in 1897, about 50% of once bald mountains backed to green.[33]

Lebanon

For thousands of years, Lebanon was covered by forests, one particular species of interest, Cedrus libani was exceptionally valuable and was almost eliminated due to lumbering operations for such purposes as the construction of King Solomon’s great temple and palace[34]. Virtually every ancient culture that shared the Mediterranean Sea harvested these trees from the Phoenicians who used cedar, pine and juniper to build their famous boats to the Romans, who cut them down for lime-burning kilns, to early in the 20th century when the Ottomans used much of the remaining cedar forests of Lebanon as fuel in steam trains[35]. Despite two millennia of deforestation, forests in Lebanon still cover 13.6% of the country, and other wooded lands represent 11%[36].

Law No. 558, which was ratified by the Lebanese Parliament on April 19, 1996, aims to protect and expand existing forests, classifying all forests of cedar, fir, high juniper (juniperus excelsa), evergreen cypress (cupressus sempervirens) and other trees, whether diverse or homogeneous, whether state-owned or not as conserved forests.[37].

Since 2011, more than 600,000 trees, including cedars and other native species, have been planted throughout Lebanon as part of the Lebanon Reforestation Initiative, which aims to restore Lebanon's native forests[38]. Projects financed locally and by international charity are performing extensive reforestation of cedar being carried out in the Mediterranean region, particularly in Lebanon and Turkey, where over 50 million young cedars are being planted annually.

The Lebanon Reforestation Initiative has been working since 2012 with tree nurseries throughout Lebanon to help grow stronger tree seedlings that are better suited to survive once planted[39].

Turkey

4000 years ago Anatolia was 60% to 70% forested:[40] although the flora of Turkey remains more biodiverse than many European countries deforestation occurred during both prehistoric[41] and historic times, including the Roman[42] and Ottoman[43] periods.

Since the first forest code of 1937 the official government definition of 'forest' has varied,[44] but according to the current definition 21 million hectares are forested (but only about half 'productive'), an increase of about 1 million hectares over the past 30 years.[45] However according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization definition of forest[46] about 12 million hectares was forested in 2015[47], about 15% of the land surface.

However according to the World Resources Institute “Atlas of Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities” the reforestation opportunities are vastly greater.[48] This could help limit global warming in Turkey. 50 million hectares are potential forest land, and to help preserve the biodiversity of Turkey more sustainable forestry has been suggested.[40]

United States

It is the stated goal of the US Forest Service to manage forest resources sustainably. This includes reforestation after timber harvest, among other programs.[49]

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service shows that area of U.S. forest was about 46% of total land in 1630, but it was decreased to 34% in 1910. After 1910, the forest area is almost constant although U.S. population has been increasing.[50] In the late 19 century, the USDA Forest Service was established to solve natural disasters due to deforestation, and Reforestation programs and laws such as The Knutson-Vandenberg Act (1930) were implemented. USDA Forest Service mentions reforestation is required to support natural regeneration and keeps researching about effective ways to restore forests.[51]

Pakistan

In the year 2018, Pakistan's prime minister declared, that he will plant 10 billions trees in next 5 years[52].

Organizations

Trees for the Future has assisted more than 170,000 families, in 6,800 villages of Asia, Africa and the Americas, to plant over 35 million trees.[53]

Wangari Maathai, 2004 Nobel Peace Prize recipient, founded the Green Belt Movement which planted over 47 million trees to restore the Kenyan environment.[54]

Shanghai Roots & Shoots, a division of the Jane Goodall Institute, launched The Million Tree Project in Kulun Qi, Inner Mongolia to plant one million trees to stop desertification and alleviate global warming.[55][56]

Criticisms

Reforestation competes with other land uses such as food production, livestock grazing and living space for further economic growth. Reforestation often has the tendency to create large fuel loads, resulting in significantly hotter combustion than fires involving low brush or grasses. Reforestation can divert large amounts of water from other activities. Reforesting sometimes results in extensive canopy creation that prevents growth of diverse vegetation in the shadowed areas and generating soil conditions that hamper other types of vegetation. Trees used in some reforesting efforts (e.g., Eucalyptus globulus) tend to extract large amounts of moisture from the soil, preventing the growth of other plants.

There is also the risk that through a forest fire or insect outbreak much of the stored carbon in a reforested area could make its way back to the atmosphere.[8]:1456 Reduced harvesting rates and fire suppression have caused an increase in the forest biomass in the western United States over the past century. This causes an increase of about a factor of four in the frequency of fires due to longer and hotter dry seasons.[8]:1456

See also

- 10,000 Trees for the Rouge Valley, a reforestation program in Toronto, Canada

- Aerial reforestation

- Forest gardening

- Forest restoration

- Forestry

- Hemp

- Greenland Arboretum

- Hoedads Reforestation Cooperative

- Jewish National Fund

- Land rehabilitation

- Natural landscape

- Plant A Tree Today Foundation

- Pottiputki (tool)

- Restoration ecology

- Revegetation

- Rewilding (conservation biology)

- Richard St. Barbe Baker

- ”The Man Who Planted Trees” (French title L'homme qui plantait des arbres), a tale by French author Jean Giono, published in 1953, and made into an animated film in 1987

- Tree credits

- Tree planting

- Tubestock

- Deforestation and climate change

References

- ↑ "Reforestation - Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ↑ Gillis, Justin (2016-05-16). "In Latin America, Forests May Rise to Challenge of Carbon Dioxide". NYT. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-11-11. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

- ↑ "Sustainable Forest Management". Key Timberland Statistics. Weyerhaeuser. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 29 December 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ↑ "Forest plantation yields in the tropical and subtropical zone". Forestry Department. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "Reforestation and Afforestation". Green Collar Association. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ Wood well, G.M.; North, WJ (1988-12-16). "CO2 Reduction and Reforestation". Science. 242 (4885): 1493–1494. doi:10.1126/science.242.4885.1493-a. PMID 17788407.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Canadell, J.G.; M.R. Raupach (2008-06-13). "Managing Forests for Climate Change" (PDF). Science. 320 (5882): 1456–1457. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.573.5230. doi:10.1126/science.1155458. PMID 18556550.

- ↑ "Shanghai Roots & Shoots -". jgi-shanghai.org.

- ↑ "Million Tree Project :: Home". mtpchina.org.

- ↑ "Five tree fee for a Java wedding". BBC News. 2007-12-03. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- 1 2 "A changing climate of opinion?". The Economist. 387: 93–96. 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ↑ Adam, David (2009-02-18). "Fifth of world carbon emissions soaked up by extra forest growth, scientists find". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- 1 2 Streck, C.; S.M. Scholz (2006). "The role of forests in global climate change: whence we come and where we go". International Affairs. 82 (5): 861–879. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2006.00575.x.

- ↑ "African countries are building a "Great Green Wall" to beat back the Sahara desert".

- ↑ "Real happenings and Facts". naturne.blogspot.com.

- ↑ "Indicator: Forest area". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. August 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "How does the forest industry contribute to the economy?". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. 2014-08-26. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Sustainable forest management in Canada". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. 2013-04-16. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Deforestation in Canada: Key myths and facts". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. 2013-06-27. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "China to plant 26 billion trees over next decade - People's Daily Online".

- ↑ ?

- ↑ Breyer, Melissa (January 11, 2018). "China is planting 16.3 million acres of forest this year". Treehugger. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Chow, Lorraine. "China to Plant New Forests the Size of Ireland This Year". Ecowatch. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Grußwort - Bundeswaldinventur". bundeswaldinventur.de.

- ↑ "Record 66 million trees planted in 12 hours in India". 2017-07-04.

- ↑ "The Man Who Has Created 33 Forests in India - He Can Make One in Your Backyard Too!". 2014-07-11.

- ↑ Brand, David; Moshe, Itzhak; Shaler, Moshe; Zuk, Aviram; Riov,, Dr Joseph (Year 2011). Forestry for People (PDF). UN. pp. 273–280. Retrieved 30 September 2018. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Afforestation in Israel". Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael Jewish National Fund. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ "Annual Report on Forest and Forestry in Japan" (PDF). Forestry Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Japan. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Change in Forest Cover (2016)" (PDF). The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery, Forestry Agency. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Promotion of International Efforts (2016)" (PDF). The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "日光 足尾 体験植樹 案内".

- ↑ "Forest and landscape restoration in Lebanon". Britannica. Archived from the original on 2018-03-17. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ↑ "Lebanon National Forest Program 2015-2025, Ministry of Agriculture" (PDF). line feed character in

|title=at position 8 (help) - ↑ "Forest and landscape restoration in Lebanon". FAO. 29 April 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ "Lebanese Forest Conservation Law". Jabal Rihan. 24 July 1996. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ↑ "Restoring Lebanon's cedar forests". Share America. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- ↑ "Sowing Seeds Today for a Better Tomorrow". Lebanon Reforestation. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- 1 2 Colak and Rotherham (2006). "A REVIEW OF THE FOREST VEGETATION OF TURKEY: ITS STATUS PAST AND PRESENT AND ITS FUTURE CONSERVATION" (PDF). Biology and Environment: Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 106 B, NO. 3: 343–354.

- ↑ Willcox, G. H. (1974). "A History of Deforestation as Indicated by Charcoal Analysis of Four Sites in Eastern Anatolia". Anatolian Studies. 24: 117–133. JSTOR 3642603.

- ↑ Hughes, J.D. (2010). "Ancient Deforestation Revisited". Journal of the History of Biology. 44 (1): 43–57. doi:10.1007/s10739-010-9247-3. PMID 20669043.

- ↑ "Conference Review: "Environmental History of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey", University of Hamburg, 27-28 October 2017". H Net.

- ↑ LUND, H. Gyde (2014). "WHAT IS A FOREST? DEFINITIONS DO MAKE A DIFFERENCE AN EXAMPLE FROM TURKEY". Avrasya Terim Dergisi. 2 (1): 1–8.

- ↑ "Turkey Forests". General Directorate of Forestry. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ "GLOBAL FOREST RESOURCES ASSESSMENT 2015: COUNTRY REPORT: Turkey" (PDF). FAO.

- ↑ "GLOBAL FOREST RESOURCES ASSESSMENT 2015 Desk reference" (PDF). FAO.

- ↑ "Atlas of Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ "Forest Service Chief testifies before Senate appropriations committee on 2013 agency budget". US Forest Service. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Forest Resource Facts and Historical Trends" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "Reforestation Overview". U.S. FOREST SERVICE Caring for the land and serving people. U.S. FOREST SERVICE Caring for the land and serving people. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Chow, Lorraine (30 July 2018). "Pakistan's Next Prime Minister Wants to Plant 10 Billion Trees". Ecowatch. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Trees for the Future Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Greenbelt Movement".

- ↑ "Shanghai Roots & Shoots".

- ↑ "The Million Tree Project".

Further reading

- Bonan, G. B. (2008). "Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests". Science (Submitted manuscript). 320 (5882): 1444–1449. doi:10.1126/science.1155121. PMID 18556546.

- Scheil, D.; Murdiyarso, D. (2009). "How Forests Attract Rain: An Examination of a New Hypothesis". BioScience. 59 (4): 341–347. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.4.12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reforestation. |

- Tropical Reforestation

- Plant a Tree and Become Carbon Neutral

- Brazilian "Mata Atlantica" reforestation initiative

- Reforestation Carbon Offsets

- "Perpetual Timber Supply Through Reforestation as Basis For Industrial Permanency: The Story Of Bogalusa" By Courtenay De Kalb, July 1921

- Saimiri Wildlife; Reforestation for endangered wildlife, side provides many pictures.

- A tree a day, keeps the carbon away

- Trees and climate change: a practical guide for woodland owners and managers

- Floresta, a Christian nonprofit with a reforestation and poverty world mission.

- Plant with Purpose

- Shanghai Roots & Shoots - Million Tree Project

- Reforestation Information