2016 Brussels bombings

| 2016 Brussels bombings | |

|---|---|

| Part of Islamic terrorism in Europe (2014–present) (the spillover of the Syrian Civil War) | |

| |

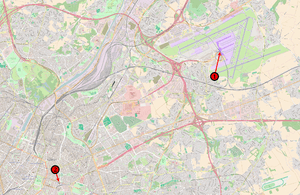

| Location | Brussels Airport in Zaventem and Maalbeek metro station in Brussels, Belgium |

| Coordinates | |

| Date |

22 March 2016 07:58–09:11 (UTC+1) |

| Target | Civilians and transport hubs |

Attack type | Suicide bombings, nail bombing, mass murder |

| Weapons | TATP explosives |

| Deaths | 35 (32 victims, 3 perpetrators)[1][2] |

Non-fatal injuries | 340[3] (62 critical)[4][5] |

| Perpetrator | Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant[6] |

| Assailants |

|

On the morning of 22 March 2016, three coordinated suicide bombings occurred in Belgium: two at Brussels Airport in Zaventem, and one at Maalbeek metro station in central Brussels.[10] Thirty-two civilians and three perpetrators were killed, and more than 300 people were injured. Another bomb was found during a search of the airport. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) claimed responsibility for the attacks.[11]

The perpetrators belonged to a terrorist cell which had been involved in the November 2015 Paris attacks. The Brussels bombings happened shortly after a series of police raids targeting the group. The bombings were the deadliest act of terrorism in Belgium's history. The Belgian government declared three days of national mourning.

Background

Belgium is a participant in the ongoing military intervention against ISIL, during the Iraqi Civil War.[12] On 5 October 2014, a Belgian F-16 dropped its first bomb on an ISIL target, east of Baghdad.[13] On 12 November 2015, Iraq warned members of the coalition that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of ISIL, had ordered retaliatory attacks on countries involved in the coalition against ISIL.[14]

Belgium has more nationals fighting for jihadist forces as a proportion of its population than any other Western European country, with an estimated 440 Belgians having left for Syria and Iraq as of January 2015.[15][16] The Guardian cited estimates suggesting that Belgium has supplied the highest per capita number of fighters to Syria of any European nation, with 350 to 550 fighters, out of a total population of 11 million that includes fewer than 500,000 Muslims.[17] Exaggerated reporting claimed Belgium's weak security apparatus and competing intelligence agencies made it a hub of jihadist-recruiting and terrorist activity.[18] In fact, Belgium faces the same problems as other European countries with regards to jihadist terrorism.[19] According to Kenneth Lasoen, security expert at Ghent University, the attacks happened more as a result of policy failure rather than intelligence failure.[20]

Terrorist cells in Brussels

Before the bombings, several Islamist terrorist attacks had originated from Belgium, and a number of counter-terrorist operations had been carried out there.[21] In May 2014, a gunman with ties to the Syrian Civil War attacked the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels, killing four people.[22][23] In January 2015, anti-terrorist operations against a group thought to be planning a second Charlie Hebdo shooting had included raids in Brussels and Zaventem. The operation resulted in the deaths of two suspects.[24][25] In August 2015, a suspected terrorist shot and stabbed passengers aboard a high-speed train on its way from Amsterdam to Paris via Brussels, before he was subdued by passengers.[26]

The perpetrators involved in the November 2015 attacks in Paris were based in Molenbeek, and Brussels was locked down for five days to allow the police to search for suspects. On 18 March 2016, 4 days before the bombings, Salah Abdeslam, a suspected accomplice in those attacks, was captured after two anti-terrorist raids in Molenbeek that killed another suspect and injured two others. At least one other suspect remains at large.[27][28][29] During interrogation, Abdeslam was presented with photographs of the Bakraoui siblings, who would later be suspected of committing the attacks in Brussels three days later.[30] Belgian investigators believe that Abdeslam's arrest may have hastened the Brussels bombings.[31] According to the Belgian Interior Minister, Jan Jambon, who spoke after the bombings, authorities knew of preparations for an extremist act in Europe, but they underestimated the scale of the attack.[32]

Attacks

- 7:55 – The three suspected attackers arrived at the airport in a taxi.[33]

- 7:58 – Two explosions occurred in the airport's check-in area, 9 seconds apart.[34][35]

- 8:20 – Rail transport to the airport is halted; road closures begin.[36]

- 9:04 – Belgium raises the terror threat level to its highest level.[37]

- 9:11 – Explosion in Brussels Maalbeek metro station kills at least 20 people.[38]

- 9:27 – All public transport is suspended in the city.[36]

- 11:15 – Eurostar rail journeys between London and Brussels are cancelled until further notice.[39]

- ≈ 17:14 – Belgian police detonate a suspicious package at Brussels Airport.[40]

- ≈ 19:30 – A police raid in Schaerbeek finds a nail bomb and an ISIL flag.[41]

There were three coordinated attacks: two nail bombings at Brussels Airport, and one bombing at Maalbeek metro station.[36]

Brussels Airport

Two suicide bombers, carrying explosives in large suitcases, attacked a departure hall at Brussels Airport in Zaventem. The first explosion occurred at 07:58 in check-in row 11; the second explosion occurred about nine seconds later in check-in row 2. The suicide bombers were visible in CCTV footage.[42] Some witnesses said that before the first explosion occurred, shots were fired and there were yells in Arabic. However, authorities have stated afterwards that no shots were fired.[43][44][45]

A third suicide bomber was prevented from detonating his own bomb by the force of a previous explosion.[46] The third bomb was found in a search of the airport and was later destroyed by a controlled explosion.[40] Belgium's federal prosecutor confirmed that the suicide bombers had detonated nail bombs.[47]

Maalbeek metro station

Another explosion took place just over an hour later in the middle carriage of a three-carriage train at Maalbeek metro station, located near the European Commission headquarters in the centre of Brussels, 10 kilometres (6 mi) from Brussels Airport. The explosion occurred at 09:11 CET.[36][48][49]

The train was travelling on line 5 towards the city centre, and was pulling out of Maalbeek station when the bomb exploded.[50][51][52] The driver immediately stopped the train and helped to evacuate the passengers.[53][54] The Brussels Metro was subsequently shut down at 09:27.[36]

Victims

| Citizenship | Deaths |

|---|---|

| 13 | |

| 4 | |

| 2 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| Total* | 32 |

In the bombings, 35 people, including three suicide bombers, were killed and over 300 others were injured, 62 critically. Including the attackers, seventeen bodies were recovered at Brussels Airport and fourteen at the metro station.[56] Four people later died of their wounds in hospital.[57] Eighty-one others were injured at the airport, while the rest were injured at the metro station.[58] The bombings were the deadliest act of terrorism in Belgium's history.[59]

Fourteen of the deceased were Belgian nationals; four were Americans; two each were from the Netherlands and Sweden; and the remaining ten each hailed from a different nation.[56] Among the fatalities at Zaventem was André Adam, former Belgian Permanent Representative to the United Nations who later served as Ambassador to the United States.[60][61]

Suspects

Profiles

A total of five attackers were involved, with three of them dying in suicide bombings and the remaining two arrested in the weeks after. All had involvement in the planning and organization of the November 2015 Paris attacks. They were identified and named as:

- Ibrahim El Bakraoui: aged 29. Committed a suicide bombing at Brussels Airport. In 2010, he had been involved in an attempted robbery at a currency exchange office and a subsequent shootout with police that left one officer injured. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison but was paroled in 2014 under the condition that he did not leave the country; he was sought by authorities when he violated those conditions.

- Najim Laachraoui: aged 24. Committed a suicide bombing at Brussels Airport alongside Ibrahim El Bakraoui. He reportedly travelled to Syria in 2013, under a false ID.

- Mohamed Abrini: born 27 December 1984. Abrini assisted Ibrahim El Bakraoui and Najim Laachraoui in the airport bombings but failed to detonate his bomb. Arrested on 8 April 2016. He was a childhood friend of brothers Salah Abdeslam and Brahim Adbeslam, who were both involved in the November 2015 attacks in Paris, and is suspected of assisting Salah Abdeslam in his escape following the attacks. He is also suspected of having fought for the Islamic State in Syria.

- Khalid El Bakraoui: aged 27, the younger brother of Ibrahim El Bakraoui. Committed the suicide bombing at the Maalbeek metro station. In 2011, he was convicted of several carjackings, the possession of a number of Kalashnikov rifles, and a 2009 bank robbery and kidnapping. After being released in 2015, El Bakraoui failed to appear for his parole appointments and abandoned his address. He was later served with three arrest warrants, one from Interpol, one international, and one European.

- Osama Krayem: aged 24. Krayem assisted Khalid El Bakraoui in the suicide bombing at the metro station. When he was eleven, he participated in a Swedish documentary film about the integration of migrants into Swedish society. Krayem is believed to have been radicalized by videos of Anwar al-Awlaki, and to have been fighting for ISIL since 2014. Before the bombings, he was one of Europe's most wanted fugitives.

In security camera video of Brussels Airport, Ibrahim El Bakraoui, Laachraoui, and Abrini[49] were seen pushing suitcases believed to have contained the bombs that exploded in the departure hall. A taxi driver who drove them to the airport said he tried to help the men with their luggage but they ordered him away.[32] Initial reports elaborated El Bakraoui and Laachraoui each apparently wearing a glove which may have concealed detonators to the explosives.[65] This was later proven to be untrue, with both being barehanded.[66]

Investigation

Within 90 minutes of the airport attack, the area around an apartment in Schaerbeek, a northern district of Brussels, was cordoned off by police. The authorities received a tip-off from a taxi driver once they released photos of the suspects several hours after the attacks.[67] Inside the home, they discovered a nail bomb, 15 kilograms (33 lb) of acetone peroxide, 151 litres (33 imp gal; 40 US gal) of acetone, nearly 30 litres (7 imp gal; 8 US gal) of hydrogen peroxide, other ingredients for explosives, and an ISIL flag.[41][68] At least one resident reported unusual smells to the police, resulting in Agent de Quartier policeman Philippe Swinnen visiting the building twice in three months, but not entering.[69]

Authorities also found a laptop belonging to Ibrahim El Bakraoui, inside a waste container near the house.[70] The laptop had a suicide note stored on it, in which Ibrahim stated that he was "stressed out", felt unsafe, and was "afraid of ever-lasting eternity".[71] It also contained images of the home and the office of the Belgian Prime Minister, Charles Michel, among information on multiple other locations in Brussels.[72]

Numerous related arrests followed after the bombings. As of 26 March, twelve men had been arrested in connection with the bombings.[73]

Aftermath

Raids and searches were made across Belgium, while security was heightened in a number of countries as a result of the attacks.[74][75]

Belgium

belle_-_22_mars_2016.jpg)

Authorities temporarily halted air traffic to the airport and evacuated the terminal buildings.[43] The airport was to be closed to passenger traffic and reopening date postponed several times with a projected reopening date of 29 March.[76] The Berlaymont building, which is near Maalbeek station and is the headquarters of the European Commission, was placed in lockdown. Controlled explosions were carried out on suspicious objects around Maalbeek station.[77]

All public transport in the capital was shut down as a result of the attacks.[78] Brussels-North, Brussels-Central, and Brussels-South stations were evacuated and closed, and Eurostar journeys to Brussels Midi station were cancelled. All trains from Paris to Brussels were also cancelled. Taxis in Brussels transported passengers free-of-charge for the duration of the lockdown.[79] Paris Nord railway station, with services to Brussels, was also temporarily closed.[80]

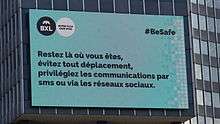

The National Security Council raised the terror alert level in the country to the highest level following the attacks.[81] The government warned that some perpetrators might still be at large and urged citizens to reach friends and family using social media to avoid congesting the telephone networks.[82] The threat level was lowered again on 24 March, and the government expanded the military protection of potential targets, that had been in place since January 2015, to include more soft targets and public places (Operation Vigilant Guardian).[83]

The country's two nuclear power plants – Tihange and Doel – were partially evacuated as a precaution.[84]

Temporary border checks were implemented by Belgian and French authorities at some major crossings on the France-Belgium border.[85]

The federal government announced three days of national mourning,[86] lasting from Tuesday until Thursday, and flags were flown at half-mast on public buildings.[87] They also held a one-minute silence at noon local time on 23 March,[86] which ended with spontaneous applause and chants of "Vive la Belgique" in Place de la Bourse.[88]

Also on 23 March, Belgian Muslim groups, such as the League of Imams in Belgium and Executive of the Muslims in Belgium, publicly condemned the bombings and expressed their condolences to the victims and their families.[89]

The airport was closed on 22 March, with reopening postponed several times. On 29 March, an operational test was performed. The official reopening date was scheduled to be announced on 30 March.[90] A post-reopening target of 800–1,000 passengers per hour was projected, compared to pre-bombing traffic of 5,000 passengers per hour. The delay in the reopening was attributed to extensive damage to the building's infrastructure. A temporary terminal was planned for use after the reopening.[91] When the airport reopened, only Brussels Airlines would serve the airport, but other airlines would be allowed to return later.[92]

On 29 March, it was revealed that Ibrahim and Khalid El Bakraoui were released from prison due to a law introduced in 1888 known as Lejeune, which allows inmates to be released after serving a third of their sentence. Belgian Interior Minister Jan Jambon stated that the governing parties had agreed to update the law in 2014. The Lejeune law first came under scrutiny after serial killer and child molester Marc Dutroux was released from prison in 1992.[93]

Airport businesses were affected. Hotel closures included the Sheraton Brussels Airport Hotel[94] and Four Points by Sheraton Brussels.[95] Cargo flights resumed on 23 March.[96] Car rental offices were also closed.[97]

Following memorials to the victims, disturbances broke out, resulting in riot police using water cannons to disperse violent right-wing protesters against ISIL.[98][99][100]

On 30 March, plans to reopen the airport were cancelled again due to a strike by airport police over a dispute over inadequate security.[101] The dispute was resolved, and the airport was later scheduled to be reopened on 3 April. On that day, a Brussels Airlines flight left for Faro and a flight to Athens and Turin was scheduled for the same day. Upon reopening, only passengers were allowed to enter a temporary departure hall and security checkpoints were implemented at the roadway to the airport. Only car and taxi traffic were allowed to enter but public transit remained suspended.[102] Hotel business revenue in Brussels had been cut in half since the airport closure.[103]

On 1 April, religious leaders in Brussels gathered together for a memorial to the victims of the bombings. They expressed their desire to spread a religious message of unity throughout Belgium, and to combat extremism.[104]

On 25 April, the Maalbeek metro station reopened with heightened security.[105] On 1 May, the departure hall of Brussels Airport, which had sustained the most damage during the bombings, partially reopened with the airport on high alert.[106]

The mayor of Molenbeek district, Francoise Schepmans, responded by closing some mosques for "incendiary language"[107] It was also determined that of 1,600 nonprofit organisations registered in the district, 102 had links to criminial activities, 52 of which to religious radicalism or terrorism.[108]

Other countries

Soon after news of the attacks broke, security was increased, particularly at airports, railway stations and other transport hubs, in China,[109] Denmark,[110][111] France,[112] Germany,[79] Greece,[113] Indonesia,[114] Ireland,[115] Italy,[116] Japan,[117] Malaysia,[118] Malta,[119] the Netherlands,[120][121][122] the Philippines,[123] Thailand,[124] the United Kingdom,[74][125] and the United States.[126] Also, Portugal evacuated the check-in section for 20 minutes due to a suspicious abandoned bag.[127] In addition, Israel stopped flights from Europe for the rest of the day;[128] additional police were deployed to the Belgian border with the Netherlands;[129] the United Kingdom's Foreign and Commonwealth Office said the Belgian authorities were advising against non-essential travel to Brussels;[130][131] and officials at the U.S. Embassy in Brussels warned of the possibility of more attacks, recommending "sheltering in place and avoiding all public transportation".[132]

Exactly a year after these terrorist attacks, the 2017 Westminster attack occurred. It was a terror incident in London where five people were killed, including a police officer and the attacker, and dozens were injured.

Reactions

.jpg)

In a televised address to the nation on 22 March, King Philippe expressed his and Queen Mathilde's sorrow at the events. He offered their full support to members of the emergency and security services.[133]

Hours after the attack the French-language hashtag #JeSuisBruxelles (#IamBrussels) and images of the Belgian comic character Tintin crying trended on social media sites. Also, hashtags such as #ikwilhelpen (#Iwanttohelp) and #PorteOuverte (#Opendoor) were used by Brussels residents who wanted to offer shelter and assistance for people who might need help.[134][135][136] Facebook activated its Safety Check feature following the attacks.[137]

Following the bombings, several structures around the world were illuminated in the colours of the Belgian flag, including the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Trevi Fountain in Rome, the National Gallery in London's Trafalgar Square, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai[138] and One World Trade Center in New York City,[139] while the spire of the Empire State Building went dark.[139] The Toronto Sign was lit up in the colours of the Belgian flag on the night of the attacks.[140]

Governments, media outlets, and social media users received criticism in some media and academic analysis for their disproportionate emphasis placed on the attacks in Brussels over similar attacks in other countries, particularly in Turkey, which occurred days before. Similarly, reactions to the November 2015 Paris attacks were viewed as disproportionate in comparison to those of earlier bombings in Beirut.[141][142][143][144] According to Akin Unver, a professor of international affairs at Istanbul's Kadir Has University, being "selective" about terrorism is counterproductive to the global counterterrorism efforts.[145]

Parliamentary inquest

On 12 April 2016 the Belgian Federal Parliament voted to establish a parliamentary commission to investigate the circumstances of the attacks and what had gone wrong so they could not have been prevented.[146] The Commission started work on 14 April 2016 and published four reports on three aspects of the disaster: the emergency response, the security architecture, and countering radicalism.[147] The Commission interdicted the fragmentation of the Belgian security apparatus, which resulted in a lack of coordination, faulty communications, missing unity of command, insufficient integration and a multitude of rules and procedures across the institutions involved that further exacerbated the challenges of coping with the terror threat. The Commission also pointed to the structural under-funding of the security services, noting how a lack of resources and manpower left the police and intelligence services unable to process all the information about the great number of Belgian foreign fighters.[148] The Commission termed this information overload with the neologism "infobesitas".[149] The report also addressed a number of severe criticisms leveled at Belgium in the French parliamentary inquest into the November 2015 Paris attacks.[150]

Memorialisation

.jpg)

In the aftermath of the attacks, the population of Brussels reacted by creating spontaneous memorials as a societal reaction to what was perceived as a collective tragedy. In the hours following the attack, people started gathering at the city center near the former stock exchange (Place de la Bourse). Mourners wrote chalk messages on the pavement and buildings surrounding the square. Numerous messages and mementos, usually every-day objects such as mugs or hats, were left at the Bourse memorial. According to Ana Milosevic, a researcher at KU Leuven, societal tensions and the pressure for the answers about the causes and consequences of the attacks, were salient in the first days and weeks after the event. During the two months of the existence, the Bourse memorial was used as a site of contestation and negotiation of the meanings associated with the terrorist attacks.[151]

The Archives of City of Brussels were tasked by the mayor Yvan Mayeur and the city council to collect and document the societal reactions to the attacks. Over two months, the team of the archives documented the process of memorialization, also collecting some of the memorabilia left by the mourners.[152]

The first memorialization initiative included the creation of a semi-permanent (temporary) monument by the Moroccan community of Molenbeek – the part of the city from which several perpetrators of the Paris and Brussels attacks originated. Called "The Flame of Hope", the monument was placed at the main square of the municipality, however it did not attract significant societal or media attention.

Following a public competition,[153] a monument to the victims was unveiled on the first anniversary of the attacks on the pedestrianised section of rue de la Loi, between Schuman and the parc du Cinquantenaire. The monument, by Jean-Henri Compere, is called "Wounded But Still Standing in Front of the Inconceivable" and is constructed from two 20-metre (66 foot) long horizontal surfaces rising skywards.[154]

The Brussels-Capital Region also memorialised the attacks with a land-art work by Bas Smets, who planted 32 birches (one for each victim) in the Sonian Forest (Drève du Comte) as "a place of silence and meditation." The birches are connected by a circle structure and separated from the rest of the forest by a small round canal.[155][156][157]

A smaller memorial (a black plaque and a tree) was also raised by the municipality of Etterbeek in the Jardin Felix Hap.

.jpg) The impromptu memorial at Bourse

The impromptu memorial at Bourse The "flame of hope" is a sculpture created by the Moroccan artist Mustapha Zoufri in honour of the victims of the Paris and Brussels attacks

The "flame of hope" is a sculpture created by the Moroccan artist Mustapha Zoufri in honour of the victims of the Paris and Brussels attacks.jpg) Memoriel 22 mars 2016, rue de la Loi, Bruxelles

Memoriel 22 mars 2016, rue de la Loi, Bruxelles Memoriel des attentats du 22 mars 2016, Etterbeek (Jardin Felix Hap)

Memoriel des attentats du 22 mars 2016, Etterbeek (Jardin Felix Hap) Mémorial en hommage aux victimes du 22 mars en pleine Forêt de Soignes

Mémorial en hommage aux victimes du 22 mars en pleine Forêt de Soignes

See also

- 2015 New Year's attack plots (foiled attack on Brussels)

- 2017 Westminster attack (an attack that occurred one year later)

- 2017 Brussels explosive attack

- Jewish Museum of Belgium shooting

- Islamic terrorism in Europe (2014–present)

- List of Islamist terrorist attacks

- List of terrorist incidents linked to ISIL

- Terrorism in the European Union

References

- ↑ "Brussels Attacks Death Toll Lowered To 32". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels airport delays reopening, Belgium lowers attacks toll to 32". AFP. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "British victim of Brussels attacks confirmed dead as slow identification of bodies continues". The Daily Telegraph. London. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Angelique Chrisafis; Emma Graham-Harrison; James Tapper (26 March 2016). "Fayçal Cheffou charged over 'core role' in Brussels bomb attacks". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "16h30 - Bilan provisoire des victimes des attentats". Centredecrise.be. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Dearden, Lizzie (22 March 2016). "Isis supporters claim group responsible for Brussels attacks: 'We have come to you with slaughter'". The Independent. London. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Brussels attack: Man wanted in subway bombing". CNN. 24 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Suspected terror accomplice known as 'Man in the Hat' reportedly among several arrested". Fox News. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ Emily Knapp; Meghan Keneally; Julia Jacobo (24 March 2016). "6 Arrested in Brussels Police Operation after French Raids Foil Planned Terror Attack". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Lasoen, Kenneth (2017). "Indications and warning in Belgium. Brussels is not Delphi". Journal of Strategic Studies. 40 (7): 940. doi:10.1080/01402390.2017.1288111.

- ↑ "Another bomb found in Brussels after attacks kill at least 34; Islamic State claims responsibility". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Nigel Morris (27 September 2014). "Iraq: Danes send attack planes". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Belgian and RNLAF F-16s Go Dutch Supporting Iraqi Forces". Aviation Week. 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Al-Baghdadi ordered attack on anti-ISIS coalition, Iraq warned France 1 day before Paris carnage". Reuters. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ Nina Elbagir; Bharati Nailk; Laila Ben Allal (22 March 2016). "Belgium: Europe's front line in the war on terror". CNN. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Neumann, Peter. "Foreign fighter total in Syria/Iraq now exceeds 20,000; surpasses Afghanistan conflict in the 1980s". ICSR. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ Burke, Jason (2015-11-16). "How Belgium became a breeding ground for international terrorists". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ↑ "How Belgium Became a Jihadist-Recruiting Hub". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Lasoen, Kenneth (2018). "Plan B(ruxelles): Belgian Intelligence and the Terror Attacks of 2015-16". Terrorism and Political Violence. doi:10.1080/09546553.2018.1464445.

- ↑ Lasoen, Kenneth (2017). "Indications and warning in Belgium. Brussels is not Delphi". Journal of Strategic Studies. 40 (7): 951. doi:10.1080/01402390.2017.1288111.

- ↑ Lasoen, Kenneth (2018). "Plan B(ruxelles): Belgian Intelligence and the Terror Attacks of 2015-16". Terrorism and Political Violence. doi:10.1080/09546553.2018.1464445.

- ↑ Casert, Raf (25 May 2014). "Belgium ramps up security for lone suspect in Jewish Museum attack". The Globe and the Mail. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ↑ "Brussels Jewish Museum killings: Man held in Marseille". BBC News. 1 June 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ↑ "Belgian anti-terror raid in Verviers 'leaves two dead'". BBC News. 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "Belgian counterterrorism raid in Verviers leaves 2 dead, report says". CBC News. 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "France train shooting: Three hurt and man arrested". BBC News. 22 August 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ↑ "Shots in Brussels raid tied to Paris attacks". CNN. 15 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ "Gunfire in Brussels raid on 'Paris attacks suspects'". BBC News. 15 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ "Paris attacks: Salah Abdeslam 'worth his weight in gold'". BBC News. 21 March 2016. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- ↑ "In Brussels Bombing Plot, a Trail of Dots Not Connected". The New York Times. 27 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Benjamin Siegel; Alexander Mallin (22 March 2016). "Terror Arrest In Belgium Likely Accelerated Timetable for Brussels Bombings, US Lawmakers Say". ABC News. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 David Lawler; Danny Boyle; James Rothwell (22 March 2016). "Brussels attacks: suicide bomber was known militant deported from Turkey to Europe, president says - live". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels Attacks: Timeline of the Events in the Belgian Capital". NBC News. 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels explosions: What we know about airport and metro attacks". BBC News. 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Timeline of the Brussels attacks". The Guardian. 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dearden, Lizzie (22 March 2016). "Brussels attacks timeline: How bombings unfolded at airport and Metro station". The Independent. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Beslissing om metro te sluiten viel 21 minuten voor explosie in station Maalbeek". De Morgen. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ Gamio, Lazaro (22 March 2016). "What happened in the Brussels attacks? We'll show you". Washington Post. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Timeline: Brussels attacks". RTE News. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Third Brussels airport bomb destroyed in controlled explosion: governor". Reuters. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- 1 2 Alissa J. Rubin; Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura; Aurelien Breeden (23 March 2016). "Brothers Among 3 Brussels Suicide Attackers; Another Assailant Is Sought". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "What Happened at Each Location in the Brussels Attacks". New York Times. 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Brussels attacks: Zaventem and Maelbeek bombs kill many". BBC News. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Natalia Drozdiak; Gabriele Steinhauser (22 March 2016). "Brussels Rocked by Terrorist Attacks, Killing at Least 27 People". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Thomson Reuters Foundation. "Attacks on Brussels airport, metro station kill around 20 – Belgian media". Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels attacks: man in the white coat 'blown away' by other bombs". 26 March 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ↑ J.V. et A.P. (23 March 2016). "Le troisième kamikaze identifié, un testament retrouvé à Schaerbeek". RTBF Info.

- ↑ Victoria Shannon (22 March 2016). "Brussels Attacks: What We Know and Don't Know". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 Bill Chappell (22 March 2016). "Terrorist Bombings Strike Brussels: What We Know". NPR. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "How the Brussels Attacks Unfolded". abcNews. 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels Metro Survivor Describes 'Blanketed Thud' and 'Cloud of Dust' After Explosion". abcNews. 22 March 2016.

- ↑ hrt. "Vrees voor doden bij explosie in metrostation Maalbeek". De Standaard. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Second suspect believed to be involved in Brussels metro attack". The Herald. 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Le conducteur du métro attaqué à Maelbeek: "J'ai fait ce que j'avais à faire"". RTBF. 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Polish woman among Brussels victim". thenews. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Brussels airport delays reopening, Belgium lowers attacks toll to 32". AFP. 29 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ↑ "Death toll in Brussels terror attacks rises to 35". CNN. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Kim Hjelmgaard; Delphine Reuter; John Bacon (22 March 2016). "Islamic State claims responsibility for Brussels attack that killed dozens". USA Today. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Neuger James; Jonathan Stearns. "Belgium's Worst Terror Attack Ever Leaves 31 Dead in Brussels". Bloomberg Business. Bloomberg Business. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Gillian Mohney (25 March 2016). "Former Belgian Ambassador to US Among Dead in Terror Attacks". ABC News.

- ↑ Michael Pearson (25 March 2016). "'I'm very lucky'—Brussels attack survivors tell their stories". CNN.

- ↑ "Brüssel: Belgische Fahnder fassen weiteren Terrorverdächtigen". Spiegel Online. 26 March 2016.

- ↑ RTL Newmedia. "Attentats à Bruxelles: Fayçal Cheffou serait bien l'homme au chapeau". RTL Info. at Brussels Airport, just before the bombings

- ↑ "Brussels attacks: 'Man in the hat' charged with terrorism and murder as nuclear security guard killed - latest". The Telegraph. 26 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "This detail about how the suspected Brussels suicide bombers wore their gloves might have been a giveaway". Business Insider. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Barnes, Julian (13 May 2016). "Why Were the Brussels Airport Bombers Wearing Gloves? The Answer Will Surprise You". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ↑ "In Brussels Bombing Plot, a Trail of Dots Not Connected". The New York Times. 27 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ↑ "Eén verdachte wordt momenteel ondervraagd". Gazet van Antwerpen. 23 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ Andrew Higgins; Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura (26 March 2016). "In Brussels Bombing Plot, a Trail of Dots Not Connected". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Alastair Jamieson; Annick M'Kele (23 March 2016). "Brussels Attacks: El Bakraoui Brothers Were Jailed for Carjackings, Shootout". NBC News. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Zelfmoordenaar laat laptop met testament achter in vuilnisbak". De Morgen. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Raf Casert (30 March 2016). "A Belgian official says laptop used by one of the Brussels bombers contained images of the Belgian prime minister's home and office, heightening fears after last week's attacks on the airport and subway system". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels attacks: Man charged with terrorist offences". BBC News. 26 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Brussels attacks: Latest updates". BBC News. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels attacks: Police hunt Zaventem bombings suspect". BBC News. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels Airport Website: 22/03: New information on baggage and car parks - UPDATE: 24/032016 8PM". 24 March 2016. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Explosionen in Brüssel – was bisher bekannt ist" (in German). Tagesschau. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Live: Belgium terror threat raised to highest level". ABC News. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Liveblog zu Attentaten in Brüssel" (in German). Tagesschau. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels explosions: Full list of Zaventem airport diverted, cancelled and arrived flights". International Business Times UK. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Tucker Reals (22 March 2016). "Deadly explosions rock Brussels airport, subway". CBS News.

- ↑ "Belgian officials urge people to use social media in wake of bombings". The Washington Post. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ↑ Lasoen, Kenneth. "War of Nerves. The Domestic Terror Threat and the Belgian Army". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 42. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2018.1431270.

- ↑ "ISIS claims credit for attacks killing 30 in Brussels". CNN. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Julien Absalon (22 March 2016). "Attentats à Bruxelles: des contrôles renforcés à la frontière franco-belge". RTL. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Brussels attacks: Belgium mourns amid hunt for suspect". BBC News. 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Belgium to Begin 3 Days of National Mourning". The New York Times. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Krol, Charlotte (23 March 2016). "Brussels attacks: Hundreds gather for one minute silence to remember victims". The Telegraph. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ↑ F., K. (22 March 2016). "Les leaders de la communauté musulmane de Belgique condamnent les attentats de Bruxelles". RTBF. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels airport delays reopening as Belgium lowers attacks toll to 32". Yahoo! News. 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels attacks: 'Months' until airport fully reopens". BBC News. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels airport aims for limited reopening this week". Reuters. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "19th-century Belgian law allowed bombing suspects to go free". USA Today. 29 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels Bombing Announcement". Starwood Hotels & Resorts. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "Starwood Hotels & Resorts Announcement". Four Points by Sheraton Brussels.

- ↑ "Brussels airport still in lockdown — but cargo flights set to resume". JOC. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "An answer to frequently asked questions". Brussels Airport. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "Riot at Brussels attacks shrine; 13 anti-terror raids made". Northwest Herald. 28 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels Riot Police Clash With Right-Wing Protestors". Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "Riot mars Brussels attack victims shrine". Mashable. 28 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels attacks: "Our main concern is security at the airport"". BBC World Service. 30 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Tim Hume; Greg Botelho (3 April 2016). "First passenger flight leaves Brussels Airport since March 22 terror attacks". CNN. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels Airport To Reopen After Security Row". Sky News. 1 April 2016. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ "Religious leaders in unity pledge after Brussels bombings". Euronews. 1 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ↑ Bill Chappell (25 April 2016). "Brussels Reopens Metro Station Where Bombing Took Lives". NPR. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels attack: Airport reopens after ISIL attacks". Al Jazeera. 2 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "London's terror attack happened exactly a year after Brussels". The Independent. 2017-03-23. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ↑ "Belgium's Molenbeek home to 51 groups with terror links: report". POLITICO. 2017-03-20. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ↑ "China beefs up airport security after Brussels attack". Agence-France Presse. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Nordjyllands Politi (22 March 2016). "Nordjyllands Politi følger situationen i Bruxelles tæt". Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Københavns Politi (22 March 2016). "Vi er opmærksomme på det der er sket i Bruxelles. Der..." Twitter. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ @SkyNews (22 March 2016). "French Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve talks French response to #Maelbeek and #Zaventem attacks" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ↑ "Airports boost security, many flights cancelled in wake of Brussels attacks". The Toronto Star. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Fardah; Priyambodo RH (25 March 2016). "Indonesia tightens security measures following Brussels attacks". Antara. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Armed Gardaí to patrol Dublin Airport in response to Brussels attacks". Newstalk. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ "Alfano: allerta 2, ci saranno espulsioni". ANSA.it. 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Abe denounces attacks in Belgium, hikes security as ministry warns Japanese travelers". The Japan Times. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels attack: MAHB strengthens security at airports". Bernama. Astro Awani. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels blasts – Malta steps up security as a precaution". Times of Malta. 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Rutte opnieuw: 'Wij zijn met meer'". Telegraaf. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Rutte: aanslagen Brussel aanval op vrijheid en veiligheid". nos.nl. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Schiphol verscherpt maatregelen". Telegraaf (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Esmaquel, Paterno II (22 March 2016). "Aquino: Tighten airport security after Brussels explosions". Rappler. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ Suchat Sritama (24 March 2016). "Thailand offers condolences, boosts security". The Nation. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Ashley Cowburn; Lizzie Dearden; Samuel Osborne (22 March 2016). "Brussels attacks live updates: ISIL claims responsibility for bombings that have killed 31 as police launch raids". The Independent. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Alissa J. Rubin; Aurelien Breeden; Anita Raghavan (22 March 2016). "Strikes Claimed by ISIS Shut Brussels and Shake European Security". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Check-in no aeroporto de Lisboa evacuado". Correio da Manha. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ↑ "Israel Bans Incoming Flights from Europe (Temporarily)". The Jewish Press. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Brussels Blasts Knock Air Travel EU-Wide". Sky News. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ James Landale [@@BBCJLandale] (22 March 2016). "Breaking: No10 says FCO is changing travel advice to warn people against all but essential travel to Brussels" (Tweet). Retrieved 22 March 2016 – via Twitter.

- ↑ "Foreign travel advice – Belgium". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Michael Isikoff (22 March 2016). "U.S. officials believe more terrorists tied to Brussels attack are at large, plotting new strikes". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "King Philippe of Belgium's Brussels Attack Address". Gert's Royals. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "British Ex-Jihadi in emotional appeal not to join ISIS". Open Your Eyes.

- ↑ "Brussels attacks: Images from a vigil being held in Place de la Bourse". ABC News.

- ↑ Maria Khan. "Brussels attack: Tintin cries across social media with slogan 'Je suis Bruxelles'". International Business Times UK.

- ↑ Kraft, Amy. "Facebook activates Safety Check after Brussels attacks". CBS News. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Vitkovskaya, Julie (22 March 2016). "Eiffel Tower lights up in Belgian flag colors after Brussels attacks". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- 1 2 "One World Trade Center to Display Belgian Colors". NBCUniversal Media, LLC. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Joseph, Rebecca (23 March 2016). "Brussels attacks: world monuments light up in support of Belgium". Global News. Toronto, Canada. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ↑ Samuel Osborne (23 March 2016). "Brussels bombings: Social media reaction to attacks criticised as disproportionate compared to Ankara". The Independent.

- ↑ "#BrusselsAttacks: Grief, Islam and double standards".

- ↑ Mic. "These Attacks Happened Days Before Brussels — But You Probably Didn't Hear About Them". Mic.

- ↑ Mic. "A Day Before the Paris Attack, Suicide Bombers Killed 43 in Beirut". Mic.

- ↑ "Turks, Reeling From String Of Deadly Terrorist Attacks, React To Brussels Carnage: 'I Share Their Pain'". The Huffington Post. 22 March 2016.

- ↑ Lasoen, Kenneth (2017). "For Belgian Eyes Only: Intelligence Cooperation in Belgium". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 30: 479. doi:10.1080/08850607.2017.1297110.

- ↑ Belgian Chamber. "Doc 54K1752: Parlementair onderzoek belast met het onderzoek naar de omstandigheden die hebben geleid tot de terroristische aanslagen van 22 maart 2016 in de luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal en in het metrostation Maalbeek te Brussel, met inbegrip van de evolutie en de aanpak van de strijd tegen het radicalisme en de terroristische dreiging. - Enquête parlementaire chargée d'examiner les circonstances qui ont conduit aux attentats terroristes du 22 mars 2016 dans l'aéroport de Bruxelles-National et dans la station de métro Maelbeek à Bruxelles, y compris l'évolution et la gestion de la lutte contre le radicalisme et la menace terroriste". De Belgische Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers - La Chambre des Représentants de Belgique. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ↑ Lasoen, Kenneth (2018). "Plan B(ruxelles): Belgian Intelligence and the Terror Attacks of 2015-16". Terrorism and Political Violence. doi:10.1080/09546553.2018.1464445.

- ↑ Belgian Chamber (15 June 2017). Doc 54K1752/008: Parlementair onderzoek belast met het onderzoek naar de omstandigheden die hebben geleid tot de terroristische aanslagen van 22 maart 2016 in de luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal en in het metrostation Maalbeek te Brussel, met inbegrip van de evolutie en de aanpak van de strijd tegen het radicalisme en de terroristische dreiging. Derde tussentijds verslag over het onderdeel "Veiligheidsarchitectuur" - Enquête parlementaire chargée d'examiner les circonstances qui ont conduit aux attentats terroristes du 22 mars 2016 dans l'aéroport de Bruxelles-National et dans la station de métro Maelbeek à Bruxelles, y compris l'évolution et la gestion de la lutte contre le radicalisme et la menace terroriste. Troisième rapport intermédiaire, sur le volet "Architecture de la sécurité" (PDF). Brussels: Belgische Kamer van Volksvertegenwoordigers - La Chambre des Représentants de Belgique. p. 52.

- ↑ France, Assemblée Nationale (7 January 2016). Doc 3922-1: Rapport fait au nom de la commission d’enquête relative aux moyens mis en œuvre par l’État pour lutter contre le terrorisme depuis le 7 janvier 2015 (PDF). Paris.

- ↑ Milošević, Ana (24 May 2017). "Remembering the present: Dealing with the memories of terrorism in Europe". Contemporary Voices: St Andrews Journal of International Relations. 8 (2). doi:10.15664/jtr.1269 – via jtr.st-andrews.ac.uk.

- ↑ Milosevic, Ana. 2018. Historicizing the present: Brussels attacks and heritagization of spontaneous memorials. International Journal of Heritage Studies 24(1):53-65

- ↑ Concours de projets pour l'édification d'un monument commémoratif pour les attentats - Procès-verbal de la session d'information, mercredi 16/11/2016

- ↑ Tormo, Temis. "Brussels installs memorial to mark attack anniversary".

- ↑ "Monuments and commemorations planned for 22 March - Flanders Today". www.flanderstoday.eu.

- ↑ "22 mars 2016 : Un mémorial pour les victimes des attentats implanté en Forêt de Soignes". 22 March 2017.

- ↑ mildrey (28 March 2017). "Un mémorial à la mémoire des victimes des attentats de Bruxelles inauguré en Forêt de Soignes".

External links